The federal monitor set to oversee the New York City Housing Authority previously resigned as receiver in a white-collar fraud case after the Securities and Exchange Commission accused him of a conflict of interest and running up fees, THE CITY has learned.

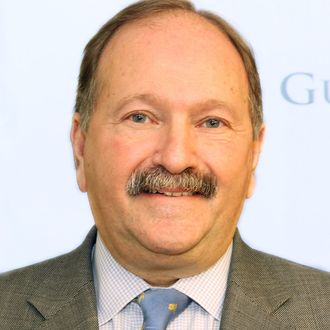

Bart Schwartz, a former federal prosecutor and head of the investigations firm Guidepost Solutions, was set to be appointed NYCHA’s monitor Monday by the Justice Department, as part of an agreement to settle federal charges of mismanagement and cover-up at the authority.

On Wednesday, THE CITY disclosed Schwartz’s appointment — and his long-standing affiliation with Lenora Fulani, an activist who’s been accused of anti-Semitic rhetoric in the past and more recently has attacked Mayor Bill de Blasio’s solutions for fixing NYCHA.

The conflict-of-interest issue arose in 2017 when Schwartz was acting as court-appointed receiver in a civil case filed by the SEC against a hedge fund known as Platinum Management.

The SEC charged Platinum with operating a Ponzi scheme, hiding huge losses from investors and in desperation using one investor’s funds to pay off others to keep the scheme afloat. When the firm collapsed, the SEC said, the hedge fund formerly claiming $1.3 billion in assets had only $609 million in the bank.

Brooklyn Federal Court judge Dora Irizarry appointed Schwartz as receiver to inventory assets still under Platinum’s control. His job was to then sort out what victimized investors would get out of what was left.

Schwartz, a former prosecutor under Rudy Giuliani, has been appointed as overseer of many cases, including as a monitor in federal cases against General Motors and Deutsche Bank. He got the Platinum receivership appointment the same year Governor Andrew Cuomo picked him to examine all state grants awarded under a controversial program known as Buffalo Billion.

Schwartz’s bio on Guidepost’s website lists the Cuomo job and a dozen other oversight appointments, but makes no reference to the Platinum receivership.

When Schwartz was tapped as receiver in December 2016, he was required to report to the judge all potential conflicts of interest that could arise in the Platinum case.

Within months of his appointment, Schwartz became embroiled in a dispute with the SEC about how to handle distribution of Platinum’s funds. The SEC lawyers wanted to resolve the receivership as soon as possible to avoid running up fees that were siphoning off much of what was left in the Platinum fund.

They estimated that, on Schwartz’s watch, the receivership had racked up professional fees that amounted to 40 percent of the cash on hand, according to a May 19, 2017, joint letter from Schwartz and the SEC to Irizarry.

“The SEC staff believes that the receivership should be wound down quickly to, among other things, minimize the accrual of professional fees (which the staff understands currently account for as much as 40 percent of the cash on hand in the Receivership),” the letter states.

In the first three months of the receivership, records show, Schwartz brought in eight other lawyers and staffers from his firm Guidepost, requested that the receivership be expanded, and in early 2017 asked that his requests for fees be kept under seal.

A spokesperson for Schwartz declined to comment.

In a June 2017 filing with the court, Schwartz revealed that the receivership had thus far run up $26.2 million in “operational expenses” from what started out as a $609 million fund. That included hiring outside law firms and accountants.

Some of Guidepost’s bills ultimately surfaced. Records filed in court show the company billed the receivership $1,311,360 for work through March 31, 2017 — including $142,080 for Schwartz’s time. Schwartz said he’d waived his normal $750-per-hour fee and billed at $600 an hour.

The SEC objected to the bill, finding more than $59,000 in costs with “insufficient justification.” Schwartz later trimmed the bill to $1,248,126, records show.

The SEC indicated Schwartz appeared to be making risky bets with Platinum investors’ money, warning that the receiver “should not make any new investments into what the SEC staff views as risky investments.”

Schwartz argued that that the companies Platinum had invested in were on shaky ground, so a quick sale would be difficult, and he contended prudent investment going forward would ultimately generate healthy returns.

Then in June 2017, one of the Platinum investors approached the SEC to “express concerns” about Schwartz, according to a letter the commission filed with the court. The investor reported discovering that Schwartz had been hired in 2013 by a law firm to defend the “ethical propriety” of a $6.5 million loan Platinum had made to the firm, the letter stated.

The firm, Milberg Weiss, was therefore a significant debtor in the Platinum cas. Schwartz had not disclosed that to the judge.

The SEC wrote to Irizarry, stating, “In the staff’s view, this prior representation constitutes an actual undisclosed material conflict of interest that would jeopardize the receivership estate’s ability to obtain value from the loan.”

The SEC noted that Schwartz had also not disclosed to the judge in the Platinum case that he’d been hired by Milberg Weiss in 2006 as an in-house monitor during a federal probe of the law firm.

When the SEC raised these issues, Schwartz conceded his prior involvement with Milberg Weiss presented an “appearance” but not an “actual” conflict and did not affect his handling of the receivership.

Still, on June 23, 2017, Schwartz agreed to withdraw as receiver. In a separate letter to the judge, he wrote, “While I strongly disagree with the SEC letter and the SEC’s assertion that I have an actual conflict of interest, I have agreed to resign and to assist in an orderly transition, rather than engage in a dispute with the SEC over my alleged conflict.”

Schwartz was selected as monitor by HUD and Manhattan U.S. Attorney Geoffrey Berman, the prosecutor who last year filed an 80-page complaint documenting NYCHA lies about failures to provide decent housing for its 400,000 tenants. The aging New York public-housing system is wracked by woes ranging from lead and mold contamination to broken elevators.

The city and NYCHA originally settled that case by agreeing to submit to a monitor’s oversight, but the federal judge overseeing the case rejected that plan as inadequate. Last month HUD, de Blasio, and NYCHA officials got around this problem when the U.S. Attorney’s Office agreed to withdraw the suit.

When Berman does that in the coming days, the judge in the case, William Pauley, will no longer have any say over matter. The new agreement requires the city to pay for the monitor’s salary, staff, and any consultants he brings in, but places no restrictions on any of these expenses.

Spokespersons for HUD and the Manhattan U.S. Attorney declined to comment on Schwartz’s stepping down from the Platinum case.