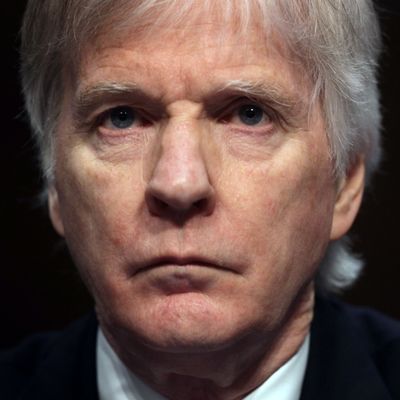

Few Americans have more on-the-ground foreign-policy experience than Ryan Crocker. Over a career spanning from the 1970s to the 2010s, he served as the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon, Kuwait, Syria, Pakistan, Iraq, and Afghanistan, as well as filling important diplomatic roles in several other countries. He survived the U.S. Embassy bombing in Beirut in 1983, and was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. Crocker opposed President Trump’s presidential candidacy in 2016, and has recently become an outspoken critic of his administration’s Afghanistan strategy. Intelligencer spoke with Crocker about why he thinks Trump’s attempt to end the conflict that has come to be known as the “forever war” is so misguided.

You’ve expressed some pretty grave concerns about the tentative peace framework being negotiated between the U.S. and the Taliban — without the Afghan government. Why do you think these talks may be a mistake?

The Taliban has insisted for the last decade and a half or so that it is always ready to sit down with the U.S., but not with the Afghan government in the room, which they style as an illegitimate puppet of the occupying force — us. After a decade and a half of saying we won’t talk under those terms, we have now conceded the point. And without knowing anything at all about the policy process in Washington, I think the symbolism is pretty clear. The only conceivable reason we would do this is because we’re done in Afghanistan, and we’re going to want to try to get the best terms we can. It completely delegitimizes the Afghan government, and that is very, very dangerous.

As the talks have progressed, the Taliban has become even more violent than usual, killing scores of Afghan officers and civilians with regularity. At the same time, they’re meeting with former Afghan officials and elders, including the former president Hamid Karzai — just not the current government. What do you make of their strategy at the moment?

Having gotten concessions on their most important demand, they know that they’re in a very good place right now, and they’re going to maximize their position. I think you’ll see them throw everything they can find into the fight. Why? Several reasons. One, to indicate that they are indeed a military force that has to be taken seriously. But they also know that the Afghan establishment, both civilian and military, will be severely demoralized by this U.S. action. So it makes sense to ramp up the violence when you’ve already got the U.S. to deliver a mortal blow to confidence in the government. You’re probably going to start seeing mass desertions in the military.

Similarly on the political side, now that we have signaled that it’s perfectly fine to talk to the Taliban without participation by the Afghan government, that’s the green light. Everybody can talk to them without the Afghan government. Did we intend this? I have no idea, but it’s certainly what we’ve got. So we may be on the fast track to extricating ourselves, but through these steps, we are decreasing dramatically the survivability of the government, including its armed forces. We have incentivized the enemy, and we have given a sign to nonviolent opponents of the government that it’s just fine to start talking to the Taliban about a political future that may include you, but certainly won’t include the current administration in Afghanistan.

You’ve also said that if U.S. troops do withdraw, it’s likely only a matter of time before the Taliban completely retakes the country.

I would expect that. I mean, in kinetic matters in complex foreign areas, you can’t be too confident of any future prediction. But again, we’re already seeing an uptick in the violence, and I think you’re probably also going to see that Afghan security forces are not putting up the fight they had done before this started.

What does that say about the Afghan military, which the U.S. has been spending so much time — almost two decades — and so much money on, trying to train into a potent fighting force? Isn’t this exactly the kind of scenario that they’re supposed to be prepared for?

Well, if you look at a relatively recent parallel, the Afghan military did fight on after the Soviet withdrawal in 1989. I think they lasted another couple of years before they eventually were consumed. You know, Afghans — they’re tough folks, whatever side of the fight they’re on. It’s just that it’s pretty hard to keep fighting in uniform when you no longer believe in the outcome, and positively dangerous, too. There’s not much point of soldiering on if all that’s going to get you is an execution by a Taliban court because you fought the soon-to-be dominant power.

So obviously we’re going to have to see what happens, but I have to think the Afghan forces are pretty severely demoralized, and that makes it pretty tough for our guys who are out there, our guys and gals out there who are involved in training.

This peace deal, if it does come to fruition, would involve the Taliban pledging that it wouldn’t allow Afghanistan to be used as a staging ground for attacks against the U.S., the way it was before 9/11 with Al Qaeda. Do you think there’s a strong chance that the Taliban would violate that promise? It seems to me that there’s little incentive to do so, given that they’ve just spent almost two decades in grinding combat as a result of hosting terrorists in the first place.

Well, that’s one way to look at it. Another way is that the Taliban decided it would continue to stand with Al Qaeda, even though it cost them the country. They would not break those ties, and I would absolutely not expect them to do so now. And what is it exactly that we’re going to do to ensure that they live up to the terms of whatever they say they’re going to do, like not allowing terrorists back into the country? It just seems fanciful to say, well, they’ll run the risk of being overthrown again. I’m not sure how ready, willing, and able we’re going to be to launch yet another military effort into Afghanistan.

I think many Americans don’t view Al Qaeda as an imminent threat, and think that they’ve been pretty much destroyed. How long can you justify an occupation if there are no attacks on U.S. soil for decades? Do we just keep the troops there forever?

Well, we keep them there until we’re powerfully persuaded in a way that will stand up to scrutiny by the American public that that threat is gone. It’s pretty hard to make that case convincingly, since it looks like the people who actually brought us the attacks are on their way back in. But somebody show me the demonstrable truth that Al Qaeda has either gone away completely, or that they have fundamentally changed their ideology. In the absence of that evidence, I think we’ve got to remember what happened before, and that the people who brought it to us are still there.

Would you prefer to keep about the level of troop commitment we have now for the foreseeable future, or send more?

I can’t say it better than President Trump did when he laid out his policy in the summer of 2017. He said that in Afghanistan we have substantial interests. We’re going to be driven not by a calendar, but by conditions. We will be there in whatever form at whatever numbers we judge to be the right way to secure our national-security interests. I mean, he got it right. It’s just that his impatience has overcome him.

And I take it you don’t have that much faith in drones to monitor this problem, as opposed to forces on the ground.

Drones are great platforms, no question. But actual control comes from, in this case, the boots on the ground. That’s where you get your detailed intel picture from — it’s where you’re able to direct operations in real time. Drones are one part of an arsenal that requires a broader set of weapons, including some minimum number of forces on the ground.

It seems that the U.S. is not negotiating from a position of strength here: President Trump clearly wants to get out, and that’s the way he’s approaching things. But has there been a time over the last 17 years where the U.S. could have negotiated from more of a position of strength than it is now?

When I was there, in 2011 and 2012, we did see some indications of [Taliban members] interested in coming in out of the cold. That started when I was there. But at that time, my position, our position was, “Sure, we’ll talk to [the Taliban] when the Afghan government asks us to do so. And when we do it, they’re gonna be in the room.” So, you know, had we sustained a more robust presence, that probably would have been about the time to do it.

I think a lot of people would say that we’ve sent tons of troops to Afghanistan since 2001, and the situation in the country has never fundamentally changed. So why should we believe that anything would change with more of them?

Well, the flip side of it is that we had over 100,000 troops there in 2011–2012. Now we’ve got 14,000 and the situation has not gotten hugely worse. So, we can sustain a commitment at or near the current levels, which costs much, much less in blood and in treasure. If we’re able to get this, you know, good-enough Afghanistan with a minimal troop commitment, that’s a pretty cheap insurance policy for our own national security.

The war has been unpopular for a long time, and has become even more so over the years. How would you frame what we’re actually doing there now? Is it about making sure the country doesn’t fall into ruin, or just about sustaining our own interests?

Both goals are tied to the whole country not going belly-up. If our non-minimal presence is a bulwark and a sustenance for the current Afghan government and its armed forces, that’s good for our own strategic safety.

And, of course, the difference between Afghanistan and Syria — and Vietnam and everything else — is that it was a Taliban-sheltered Al Qaeda, which caused 9/11. Hezbollah, as bad as they’ve been, the Iranian revolutionary guards, as bad as they are, the Syrian regime, as bad as they are — none of them have even contemplated, to our knowledge, any kind of attack into the U.S. mainland. Al Qaeda, in a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, not only thought about it, they did it. And do we really think that somehow the Taliban is kinder and gentler after 18 years in the wilderness? Why on earth would we think they are? They’re committed to their cause. They’re outlasting us. They have a level of patience we don’t.

Are you in contact with many people in the Trump administration? Do you get a sense that this policy is unpopular in the military or diplomatic core? Or are you pretty far removed from that world at this point?

I stand pretty well clear of that world, in large part. To be clear with you and with others, these are my own thoughts and conclusions drawn from publicly available information, and I’m not privy to any particular inside knowledge. That said, knowing some of the players and past situations, the only reason that you can imagine us now agreeing to talk to the Taliban without the Afghan government would be a result of negotiators being told, “We’re getting out, cut the best deal you can, cut it as quick as you can, because we’re going.” There’s no other explanation I can find for the sudden decision to reverse course on a critical policy point of the Afghan government and the chief interlocutor.

The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.