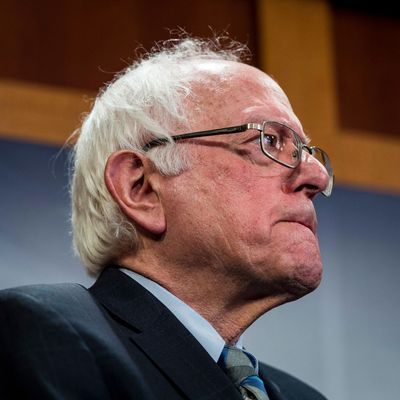

Anyone paying attention to the early stages of the 2020 presidential campaign is probably aware that Bernie Sanders, in sharp contrast to his focus in 2016, is spending a lot of time talking about foreign policy.

And as Jamelle Bouie points out, he has a distinctive international outlook that is consistent with his domestic point of view:

For him, the ideological struggle of the 21st century doesn’t pit a liberal, democratic America against illiberal, authoritarian opponents, but instead pits liberal, democratic peoples everywhere against illiberalism at home and abroad. It’s a “worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy and kleptocracy” against one toward “strengthening democracy, egalitarianism, and economic, social, racial and environmental justice.” In this conception of the world, President Trump is just one of many “demagogues who exploit people’s fears, prejudices and grievances to gain and hold on to power.”

This leads Sanders naturally towards a less sanguine view of unilateral U.S. responsibilities for promoting peace and justice through, well, massive defense spending and dubious alliances, and a greater reliance on international institutions (like the much-maligned, but indispensable United Nations) that stand above any nation or group of nations. As Bouie puts it:

For Sanders, the United States must create a global order that can constrain authoritarian states and bring democratic accountability to global capitalism. It must also embrace the cooperation necessary for tackling climate change and other transnational challenges, building “partnerships not just between governments, but between peoples” and recognizing that “our safety and welfare is bound up with the safety and welfare of others around the world.”

How does this come across to American voters at — let’s face it — a time when international issues aren’t particularly salient? That’s hard to say, though it does position him to argue for larger defense spending cuts than other Democrats might dare to propose, with all the useful things a good progressive candidate can propose to do with a new “peace dividend.”

But there’s another perspective on Sanders’s foreign policy views that makes their political appeal — and for that matter, the risk involved — clearer. For Peter Beinart, Sanders is applying the same challenge he offered in 2016 to a different set of issues:

What all this represents is a second phase of the assault on American exceptionalism that Sanders launched in 2016. Back then, Sanders challenged the domestic side of the exceptionalist creed: the belief that American capitalism — buttressed by modest regulations and welfare provisions — provides upward mobility. Now Sanders is poised to challenge exceptionalism in foreign policy: the belief that America, as a uniquely virtuous nation, can substitute its own self-interest and moral intuition for international institutions and international law.

That’s a fascinating insight. It’s often forgotten that the term “American exceptionalism,” so often identified with conservative notions of this country’s unique position in world affairs, initially referred to the idea that America’s history and social structure made it largely immune to class struggle — and for that matter, from the appeal of socialism that was so regular a feature in the politics of other advanced democracies. As Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Marks observed in a 2000 book on the subject:

The term “American exceptionalism,” first formulated by Tocqueville in the 1830s, and since used in general comparative societal analyses, became widely applied after World War I in efforts to account for the weakness of working-class radicalism in the United States ….

For radicals, “American exceptionalism” meant a specific question: Why did the United States, alone among industrial societies, lack a significant socialist movement or labor party?

As the first self-identified American socialist to run a viable major-party presidential campaign, Sanders really was implicitly rejecting the deeply embedded idea that Americans did not need the sort of safety-net programs, guaranteed benefits, and restraints on corporations that most advanced European and Asian countries took for granted, or at least regularly entertained as reasonable options. And as Beinart notes, Sanders succeeded in making it as far as he did because it turned out that younger Americans weren’t allergic to socialism, or offended at the idea that they needed the kind of economic protections available in other countries. Now, a similar generational sea-change in public opinion could make Bernie’s international views newly respectable:

Once again, Sanders’s heresies mirror the anti-exceptionalist turn among America’s young. A 2017 Pew Research poll found that Americans over the age of 30 were far more likely to say that the “U.S. stands above all other countries in the world” than to say, “There are other countries that are better than the U.S.” But among adults under 30, the latter view predominated by a margin of more than two to one.

Whether or not there is a popular majority at this point for the belief that for all its merits the United States is just another country, it’s clear enough that Sanders’s domestic and international viewpoints provide the sharpest possible contrast with Trump’s aggressively jingoistic nationalism and the MAGA agenda that goes with it. That’s worth thinking about, since the conventional wisdom has often suggested that Sanders is himself an economic nationalist whose natural constituency is among the white working-class voters Trump values so much. Looking at how and where he succeeded in 2016, it’s more plausible that Bernie really is a pied piper with unusual youth appeal because he just doesn’t speak the old language of American exceptionalism. That may or may not bode well for his 2020 prospects, but it does suggest he’s an authentic pioneer whose views have a robust future.