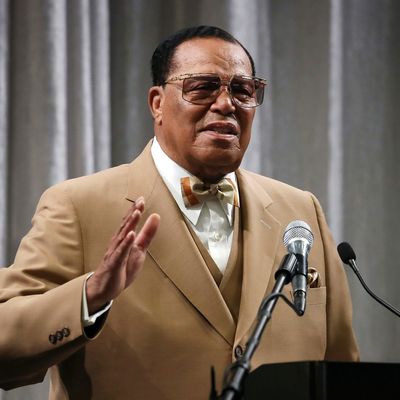

On Thursday, the Washington Post and the Atlantic provoked bipartisan outrage on social media when they published stories about Facebook’s decision to ban several people from its platform. At issue was the terminology both outlets used in describing the decision. A tweet the Post has since deleted read: “Facebook bans far-right leaders including Louis Farrakhan, Alex Jones, and Milo Yiannopoulos.” The Atlantic used similar language, also characterizing the group of leaders as “far right.”

“Do words mean anything anymore?” Ben Shapiro tweeted in response. “Farrakhan isn’t far right.” Seth Mandel agreed, accusing the publication of “disowning their own side’s bad actors and foisting the blame for their bigotry on their political opponents.” Yascha Mounk, who insisted that he “proudly subscribes” to left-wing values, described the framing as “an inability [among liberal institutions] to recognize left-wing authoritarianism” and then, “[once] its authoritarian element becomes impossible to ignore … [denying] that it is left-wing.”

None of them made reference to Farrakhan’s actual ideology, except that he is an anti-Semite, and that some progressive activists and prominent Democrats — including Barack Obama, Eric Holder, and Women’s March co-organizer Tamika Mallory — have praised him or been photographed with him. A third fact — that Farrakhan came to prominence criticizing white supremacy — likely fuels their assumption that he is part of the “left.”

But in reality, Farrakhan’s sociopolitical outlook is decidedly right wing. To the extent that such labels apply to the collectives into which black Americans have organized themselves to fight white oppression, Farrakhan is a reactionary black nationalist who has strategized often with reactionary white supremacists who share his priorities, namely racial separatism. He and his followers within the Nation of Islam espouse a philosophy of liberation rooted in religious fundamentalism, capitalist self-sufficiency, ethnonationalism, and a retreat into patriarchal family structures. That in Farrakhan’s case these values were forged in response to white racism does not make them any less conservative.

They do differ, however, from the conservatism of the modern Republican Party in key ways. Chief among them is that Farrakhan believes that he is acting in the interests of black people. The GOP — with its 89 percent white support base — holds no such illusions, and would consider it a victory if it garnered 10 percent of the black vote in a given election. This divide, acknowledged or unacknowledged, almost certainly drives much of the aversion to Farrakhan being described as “far right.”

But even if the black conservative tradition cannot be mapped directly onto the white conservative tradition, it is an equally poor fit — if not a worse one — with leftism. Going back to the black conservative movements led by Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey, the leftist commitment to pluralism and anti-capitalist critique are arguably less compatible with Farrakhan’s brand of nationalism than are the beliefs of the Trump-era GOP. (Incidentally, Farrakhan endorsed Trump in 2016.) Rejecting white supremacy breeds strange bedfellows. Ever the opportunist, Farrakhan has found common ground with figures ranging from Ku Klux Klan leader Tom Metzger to Fidel Castro. Yet, contradictory though it may seem, none of this has fundamentally changed his politics. “On issue after issue, Farrakhan’s positions on major public policies are as reactionary as those of Newt Gingrich,” wrote historian Manning Marable in 1998.

That Farrakhan has flirted with relevance for so long is attributable in part to this strategic opportunism, which allows him to cast himself as a black leader of significance even as his following dwindles. The Nation of Islam’s deep historical roots and community work in black neighborhoods makes its leader a person whom political and activist figures seeking inroads into said communities deem worth engaging — even if they rebuke his more hateful views.

And indeed, Farrakhan’s core message still has its adherents. The notion that black people will never be treated as equals by white America, and so must build their own structures to support themselves, remains as galvanizing for some today as it was for a large swathe at the time of the Million Man March. But while the structures that Farrakhan has helped build and maintain through the Nation have become safe havens for many black people, his reactionary bigotry has pushed him further into the margins of the mainstream, and aligns him more ideologically, in many ways, with the modern right. This does not make him a Republican, or a Trumpian conservative. It just means that the descriptors used by the Post and Atlantic were not wrong.