For years, Eero Saarinen’s propeller-age TWA Flight Center sat forlornly at JFK like a pinioned bird, vacant, shabby, and useless. The airline went bust in 2001; four years later, JetBlue photobombed the original with its new Terminal 5, designed by Gensler, and briefly considered sprucing up the old building as an extra lobby serving the few design aficionados who would trade convenience for an aesthetically gratifying check-in. So it’s thrilling to see Saarinen’s cathedral of flight reopen as the lobby of MCR’s $265 million TWA Hotel, looking as pale and bright and smooth as it did 57 years ago. You can once again set your windup watch by the three-sided globular clock that hangs from the central vault, run your fingers over the speckled penny tiles, and sip an Old Fashioned in the sunken lounge. It all feels like a museum of 1962.

Idlewild Airport has utterly changed since the Kennedy administration, and so has the experience of flight. Once, we dressed up and savored the privilege of travel. Now we schlep, slump, and jam ourselves into ever-tighter slots. In the routine of mass migration, holding on to your dignity costs extra. Glamour is unthinkable.

But amid the misery of the airborne herd, the reborn Flight Center is a reminder that being able to swing around the globe in a matter of hours is not something we should take for granted. Saarinen embedded modernity’s optimistic ideals in his architecture — even though the jet age was born between design and execution, so the terminal was functionally obsolete from day one. Beyer Blinder Belle has refreshed the structure for a more skeptical time, to spectacular effect. The ex-terminal can ease a layover or host a bar mitzvah now, and it also restores an architectural masterpiece to its rightful place in public view.

It’s good to dawdle here again, without a destination or a reason to spend the night but with a powerful sense of how much the building matters. A curling ribbon of influence corkscrews from the baroque into the 20th century, passing through the Art Nouveau, Gaudí, and Frank Gehry interiors where steel, glass, iron, and wood behave like draped fabric or viscous syrup. A second historical line links great concrete sculptures with thin walls that shimmy, wave, or spring into enormous domes: Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France, for example; Pier Luigi Nervi’s Palazzetto dello Sport in Rome; and Toyo Ito’s Baroque Museum in Puebla, Mexico. And a third thread follows the Industrial Age’s architecture of speed from Fiat’s Lingotto factory, designed by Giacomo Mattè Trucco in the 1930s with a spiraling ramp up to a rooftop test track, to Bjarke Ingels’s proposal for a Hyperloop portal in Dubai. (In our time, when electronic speeds are measured in nanoseconds, moving people around takes roughly as long as it did 70 years ago. Curiously, the oldest of the modern transportation technologies, rail, has evolved the most in recent years, which is why our era’s architectural poets of forward motion, Zaha Hadid and Santiago Calatrava, have both designed high-speed train stations.)

All three of these strands cross at TWA, a curvaceous concrete shell intended to evoke the experience of riding currents of air. Mechanical flight is linear, though; a plane’s trajectory describes an arc from one point to another. Saarinen rendered travel differently, as a series of spirals, swoops, and pauses — more a dance than a straight shot through the sky. His terminal balances en pointe, its vast canopy standing on four points. The bridge through the lobby is not a single arch but two arms flung toward each other, their fingertips an inch apart. As Saarinen started to sketch in the mid-1950s, he could draw on a whole repertoire of contemporary associations between curving lines, physical motion, and sex. Like the “muscular one” in Wallace Stevens’s 1955 poem “The Emperor of Ice Cream,” Saarinen formed his interiors into “concupiscent curds,” luscious white swirls like beaten egg whites or whipped cream, or polished marble limbs. That same year, Vladimir Nabokov published Lolita, in which the criminally lecherous Humbert Humbert whisks his nymphet off on a circuitous road trip: “Our route began with a series of wiggles and whorls in New England …”

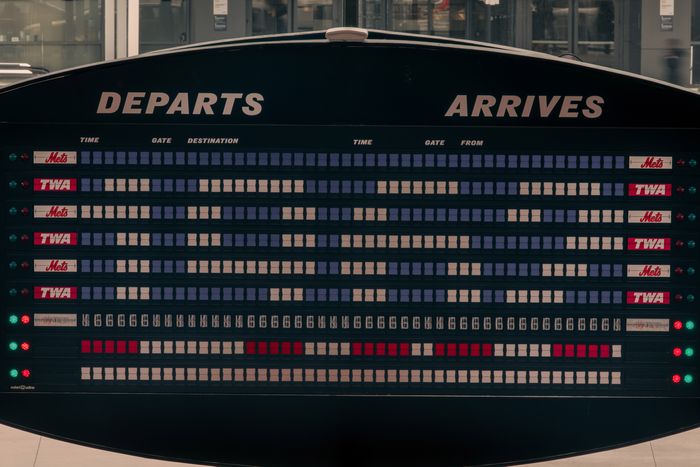

The first visitors to the Flight Center, just a few years later, would have had to be pretty straitlaced not to notice the feminine attributes of an architecture with no right angles or straight lines. Travelers entered just beneath the canopy’s protruding nub. Flight information was displayed on a humanoid face raised on a slender, curving neck and framed in a concrete bob with a widow’s peak. At boarding time, passengers passed through scarlet-carpeted tubes that rose and dipped invitingly on the way to the gates. TWA capitalized on the subliminal raunch. In 1968, the company launched a line of disposable paper uniforms called “British wench,” “French cocktail,” “Roman toga,” and “Manhattan penthouse pajamas,” some of which are preserved in the hotel’s museum display. The retro toiletries bag found in each room includes a replica of an original in-flight goodie, a Band-Aid case bearing the slogan I’M STUCK ON TWA FLIGHT ATTENDANTS.

The hotel is about stopping, not flying. Instead of implied eroticism, it offers four-hour rooms and beds with floor-to-ceiling view of planes touching down and lifting off. No longer able to evoke future excitement, it burrows down under the bedclothes of the past. You have to admire the management’s preservationist thoroughness. The whole complex, including two stolid new wings by Lubrano Ciavarra that sprout from the bird’s ribs and a conference center by Inc Architecture & Design tucked beneath the tarmac, is an eBay triumph. Every space is packed with chairs picked up from the Four Seasons auction, rotary phones converted for internet calling (parents will have to teach their kids how to dial), and refurbished furnishings by the mid-century’s marquee names: Knoll, Eames, Noguchi, and Loewy. The 90-year-old Stan Herman, who designed TWA’s uniforms in the 1970s, has returned to clothe the hotel staff. A decommissioned Lockheed Constellation L-1649A Starliner, known to aviation buffs as “Connie,” sits out back, serving out its retirement as a bar.

Such faithfulness brings up what I think of the Mad Men conundrum: At what point does the obsessive evocation of an era spill over into uncritical adulation? Can you indulge in the glamour without also pining for the sexism and segregation? The suspicion nags as you stroll through this gorgeously curated time warp, secretly hoping to bump into Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant, that you might be forgetting about the dark side of nostalgia. And then a more specific thought asserts itself: Maybe mid-century retro chic is really just a design lover’s version of MAGA.