Few New Yorkers would consider the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway an outstanding example of urban design, but the quarter-mile section at Columbia Heights is just that: an industrial-Deco masterwork, a brief note of harmony in the otherwise grim tale of the automobile and the city. Here, a major highway briefly becomes a good urban citizen: Traffic is channeled onto great stacked trays that step down to the waterfront, as if genuflecting before Manhattan; up top floats one of New York’s finest open spaces, the Brooklyn Heights promenade. This rare fusion of highway design and civic urbanism makes the recent decision to repair rather than replace the vast cantilevered structure a praiseworthy one.

It’s long been Heights lore that the viaduct and promenade were the fruits of an extraordinary organizing effort by local residents, one that handed the titanic Robert Moses a rare defeat. Moses, the story goes, hungered to cleave the fine old neighborhood with his nasty road. And, in fairness, it certainly looked like he was about to do just that.

My parents courted on the Brooklyn Heights Promenade in the 1950s, which means I might not exist were it not for the project. But the very road that helped lead my mother to the altar also destroyed the neighborhood she grew up in. Marriage got her out of impoverished Vinegar Hill, and not a moment too soon, for the coming of the BQE unleashed — there and along much of its ten-mile route — a cycle of decline that wasn’t reversed until the 1990s.

Trenched across working-class South Brooklyn, the expressway hacked apart neighborhoods already battered by the loss of port and manufacturing jobs. It laid waste to the North Heights, taking with it February House — the storied rookery where Carson McCullers, Benjamin Britten, and W. H.

Auden lived in splendid chaos. It consumed entire blocks for bridge ramps, crushed the daylight out of Park Avenue by the Navy Yard, and cleared a swath of Williamsburg wide enough to land a jumbo jet. Lewis Mumford likened it all to “the blast of an atom bomb.”

This was oddly appropriate. The Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway, as it was initially known, was intended to complete a great orbital route around the city that Moses had a begun a decade earlier with the Circumferential Parkway (today’s Belt, Southern, Laurelton, and Cross Island parkways). It would extend that loop via the elevated Gowanus Expressway toward Queens and the Grand Central Parkway. Ever creative in tapping federal coffers, Moses positioned the BQE as vital to “the defense of New York City in war,” part of a $65 million highway program announced on Armistice Day in 1940. He envisioned “ponderous units of mobile war machines” rolling down his roads.

Because the BQE had run along Hicks Street in South Brooklyn — today’s Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens — many assumed that Moses would march north on the same trajectory, driving the highway right up the Heights’s Anglo-Dutch arse. As any child with a map could see, Hicks Street was the most direct route between this latter-day Sherman and his sea. Or so it seemed.

Indeed, nothing would have made Moses happier than to beat the superior shit out of the Heights. Moses had already clashed with the community over one of his dream projects: a Brooklyn-Battery bridge. At the behest of Heights friends, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt decried the proposed span as an “eyesore perpetrated in the name of progress” in her popular New York World-Telegram column. He built a tunnel instead.

After all, this was no immigrant ghetto that quaked at the command of City Hall but one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in New York. And while its glory days were well past, Brooklyn Heights in the 1940s still had real clout — the soft-spoken, old-money clout of club and boardroom. A list of Columbia Heights residents at the time reads like a page from the Social Register — Sturgis, Talmadge, Hamilton, Fairbanks, Parke, Hale, Edwards. There is not an ethnic name among them. Most Heights folk did not mingle with Jews in the 1940s; they were certainly not going to be bossed around by one.

They could be hoodwinked, though.

Aside from a self-serving quip years later — that he was talked out of going “through the Heights” by Borough President John Cashmore — there is no evidence that Moses seriously meant to run the BQE up Hicks Street. If this alignment was considered at all, it was only briefly in the project’s early vetting stages; for taking Hicks Street would have not only been politically costly but also required condemning “very expensive property and churches,” as Moses engineer Ernest J. Clark put it.

But Moses was a Machiavellian with a penchant for grudges, and like a cat with a mouse under its paw, he was going to have a little fun. In early September 1942, surveyors were seen fiddling with theodolites and transit rods on Hicks Street. The Heights was set abuzz like a drop-kicked hornet’s nest. The Brooklyn Heights Press pulled out its biggest font typeface to DENOUNCE EXPRESS HIGHWAY, which left its readers “shocked beyond recovery.”

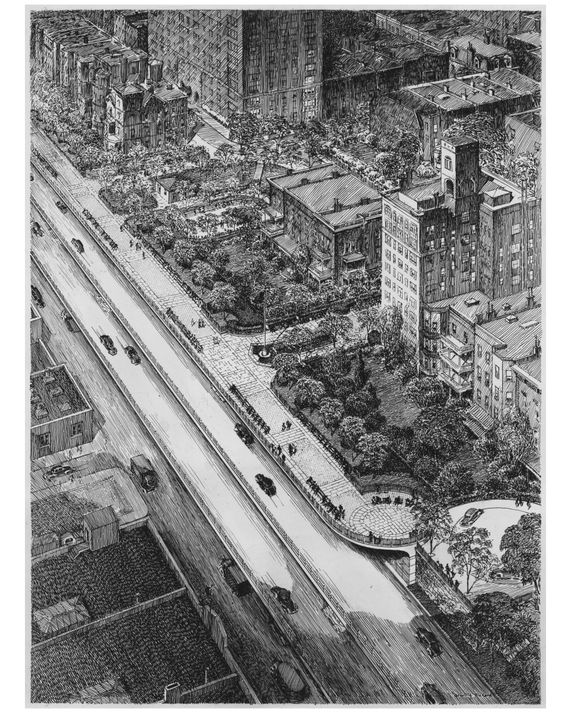

In all likelihood, Moses ordered the Hicks Street survey simply to provoke the Heights, fanning its worst-case fears so that almost any alternative would be embraced by relieved and grateful residents. That “alternative” they got was the one Moses wanted from the start — along the embankment at Furman Street. That he did so was hardly a secret. A map in the Triborough Bridge Authority’s Gowanus Improvement report, published a year before the Hicks Street survey, clearly indicates the BQE running along the Heights waterfront. Months earlier, in a June 1941 Times article about the Gowanus Parkway, Borough President Cashmore explained that the city intended “to extend this express highway route … by way of Furman Street to a connection with the Brooklyn, Manhattan and Meeker Avenue bridges.” The City Planning Commission, too, had selected the Furman Street route as early as 1939, with site planner Fred W. Tuemmler retained to design a cantilevered highway structure with the upper road at roughly the level of Columbia Heights (though sans promenade or even sidewalks).

Heights residents cheered. Local civic and business organizations unanimously backed the “new” route at the sole planning-commission hearing on the project in March 1943. Local elites convinced themselves it was timely action on their part that saved the day. One was typewriter heiress Gladys Underwood James. According to the late Henrik Krogius, James hosted a “dinner of persuasion” for Moses at her Pierrepont Place home, where she informed her guest “that the [Hicks] route would be fatal to the neighborhood … that the highway must be put along Furman Street.” The problem is that James did not move to the Heights until 1948, long after construction at Furman Street had begun.

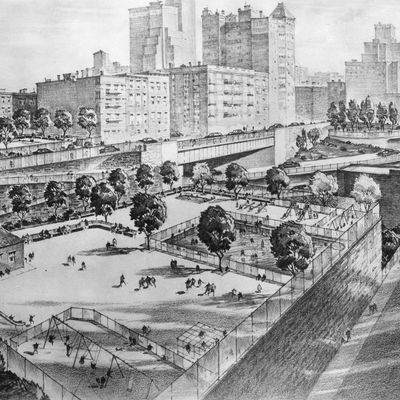

By bluffing the Heights, Moses minted political capital that diffused opposition to other aspects of the huge project: the promenade, for example. Homeowners on Columbia Heights, the most exclusive block in Brooklyn, had long opposed a public park in their backyards. In 1827, pioneering developer Hezekiah Pierrepont proposed “an open promenade … from Fulton ferry to Joralemon Street” but was rebuffed by his own neighbors. In 1903, again to no avail, the New-York Tribune promoted construction of an “imposing park or terrace” above Furman Street to afford people “an unobstructed view of New-York Harbor.” Eight years later, Newell Dwight Hillis of Plymouth Church — a keen advocate of city planning — suggested building “a boulevard one hundred feet wide, on the level of the gardens in the rear of the Columbia Heights houses.” Hillis had a true bully pulpit and yet no one heeded his call.

Robert Moses at his best — Moses the reformer, man of the people; Moses before World War II — was a latter-day Robin Hood who relished taking from the rich and giving to the poor (the “deserving” white poor, at least). The promenade was born out of the last embers of this prewar idealism. Columbia Heights residents called for a deck over the BQE but for the gardens they would lose when the embankment was condemned. Moses wanted a place for everyone, a great viewing terrace from which the breathtaking vista of Manhattan could be enjoyed by more than the privileged few.

Just before the March public hearing, Moses had consultants Andrews and Clark rework Tuemmler’s plans for a cantilevered highway structure to include a top deck spacious enough for both private gardens and a public promenade. Clarke and Rapuano, designers of many Moses-era parks and parkways (including nearby Cadman Plaza Park), were tapped to landscape it. And thus did this one short stretch of expressway become a cherished and enduring part of New York’s public realm.

Thomas J. Campanella is associate professor of city planning at Cornell University and historian-in-residence of the New York City Parks Department. His book Brooklyn: The Once and Future City will be released in September.