Donald Trump says Americans are currently living through “the greatest economy in the history of the U.S.” And while anyone familiar with mid-century growth rates will find the president’s assessment a bit hyperbolic, we’re still plausibly enjoying “the greatest economy in the history of the decade.”

America’s unemployment rate is still hovering near half-century lows. Wage growth is still about as high as it’s been since the 2008 financial crisis. Chatter about an imminent recession has faded into murmurs. On Wednesday, third-quarter GDP growth and ADP’s private-sector job-growth estimate both came in higher than expected. There is reason to think that our long, slow post-crisis expansion has already hit its peak. But for now, the “good times” are still rolling.

And working-class Americans are still hurting.

If the U.S. economy remains strong in cyclical terms, that very strength makes its persistent weaknesses — from the perspective of the median U.S. worker — all the more concerning. Absent drastic policy changes, this seems to be about as good as economic conditions are going to get. Yet a “good job” remains beyond the reach of most American workers, while a growing number of middle-class families are turning to high-interest online loans to make ends meet.

For many lower-middle-class families, the Trump era has been a subprime time.

One well-known shortcoming of the post-2008 expansion has been its lackluster rates of productivity growth. But some economic sectors have engineered remarkable innovations in recent years — the usury industry, for example.

A few short years ago, America’s subprime lenders had fallen on hard times. With state and federal regulators capping interest rates on payday loans and low-income workers finally seeing a bit of wage growth, the high-interest, short-term loan business went into decline. But when predatory finance gets disrupted, the predatory financiers get #disrupting.

As Bloomberg’s Adam Tempkin reports, subprime lenders have built a new business model atop two foundational insights: (1) The bulk of new consumer lending regulations were written to prevent short-term loans from driving very low income workers into debt traps, and (2) the lower-middle class’s wages have been rising slower than its household costs, potentially rendering many families with bad (but not terrible) credit eager to accept medium-term personal loans, even at high interest rates.

In order to shield payday-loan borrowers from usury — while preserving the ability of more financially secure individuals to access expensive forms of credit — states like California and Virginia restricted their interest-rate caps to loans smaller than $2,500. But while few subprime lenders would wish to extend more than that sum to low-income workers borrowing on a short-term basis, many have been eager to provide much larger loans to middle-income families on a long-term basis, especially since they can still legally charge such borrowers triple-digit interest rates.

As Tempkin explains:

Whereas payday loans are typically paid back in one lump sum and in a matter of weeks, terms on installment loans can range anywhere from 4 to 60 months, ostensibly allowing borrowers to take on larger amounts of personal debt … Larger loans have allowed many installment lenders to charge interest rates well in the triple digits. In many states, Enova’s NetCredit platform offers annual percentage rates between 34 percent and 155 percent.

This new online-installment model enabled lenders to increase the supply of high-interest subprime credit. But it was the U.S. economy’s shortcomings that supplied the demand: Between 2008 and 2018, the average household income for Americans with only a high-school education rose 15 percent; over that same period, overall consumer prices rose by 20 percent, housing prices by 206 percent, health care by 33 percent, and average college costs by 45 percent. Which is to say, even after Trump (and/or years of slow but steady growth) made America’s economy “great” again, working-class families were still struggling to meet the costs of keeping their children housed, insured, and well-educated.

So subprime lenders stepped in to fill the holes that Uncle Sam’s policy failures had left in such families’ budgets:

About 45 percent of online installment borrowers in 2018 reported annual income over $40,000, according to data from Experian Plc unit Clarity Services, based on a study sample of more than 350 million consumer loan applications and 25 million loans over the period. Roughly 15 percent have annual incomes between $50,000 and $60,000, and around 13 percent have incomes above $60,000.

For Tiffany Poole, a personal-bankruptcy lawyer at Poole, Mensinger, Cutrona & Ellsworth-Aults in Wilmington, Delaware, Middle America’s growing dependency on credit has fueled a marked shift in the types of clients who come through her door.

“When I first started, most filings were from the lower class, but now I have people who are middle class and upper-middle class, and the debts are getting larger,” said Poole, who’s been practicing law for two decades. “Generally, the debtors have more than one of these loans listed as creditors.”

Progressives (including myself) often describe subprime lending in moralistic terms, and not without reason: Many of the industry’s practices are profoundly abusive. That said, here is some truth to the claim that subprime lenders are meeting a genuine consumer need. And some subprime borrowers surely benefit from securing expensive credit in a time of crisis. But in the wealthiest country in human history, none should have to.

Sure, the typical worker’s wages might not be great, but the other aspects of her job are also bad.

Lackluster wage growth isn’t the Trump economy’s sole flaw. In fact, for working people, it’s more like a silver lining.

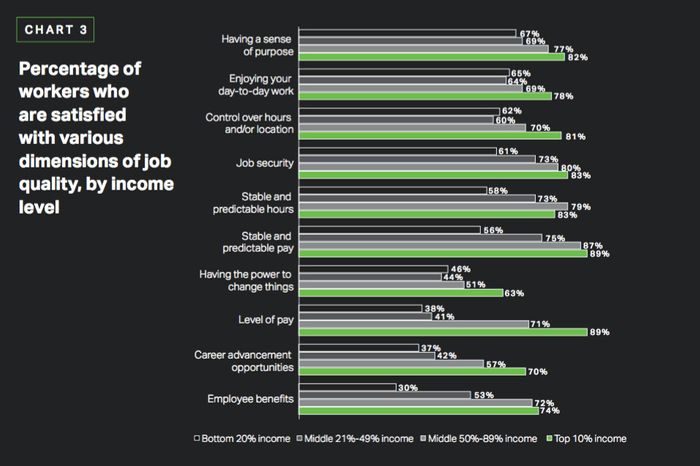

A recent Gallup survey on job quality in the United States illuminates this point. To assemble a more fine-grained portrait of American working life than federal wage and employment data can provide, the pollster (in partnership with the Omidyar Network, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Lumina Foundation) asked 6,600 U.S. workers what they saw as the defining characteristics of a “good” job, then used their answers to construct a “job-quality index.” The resulting metric reflects not only a given job’s level of wages and benefits but also whether it offers career-advancement opportunities, stable hours, a sense of purpose, the ability to change unsatisfying aspects of one’s employment, and job security, among other things.

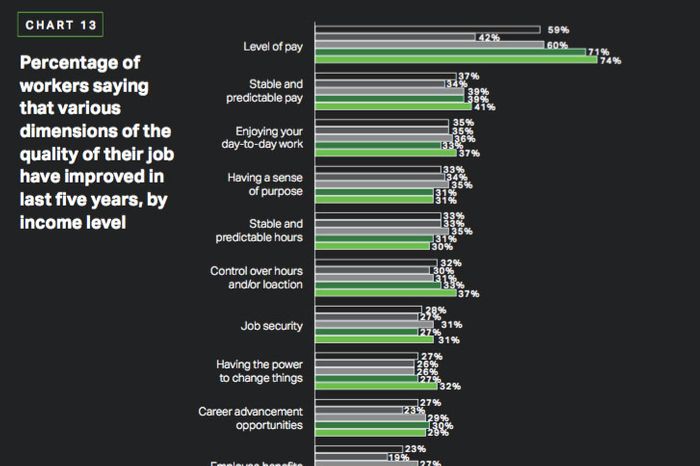

Gallup’s headline finding is that, as measured by its index, only 40 percent of Americans currently have “good” jobs. But a more telling (and less ambiguous) finding from its survey may be this: While 59 percent of U.S. workers say their wages have increased over the past five years, no more than 37 percent say any other key marker of job quality has improved over that period. In fact, roughly as many workers say their job’s noncash benefits have gotten worse in recent years (21 percent) as say they’ve gotten better (23 percent). Meanwhile, majorities report no gains in their job’s sense of purpose, enjoyability, or the stability and predictability of its wages — all factors that respondents rated as being more important to job quality than overall pay.

Crucially, as one might expect, the less-tangible determinants of job quality in the United States are nearly as inequitably distributed as labor income (although no determinant is more inequitably distributed than satisfactory employment benefits).

Whether the threshold Gallup sets for a “good” job is correct is a debatable proposition. But the pollster finds that 79 percent of those who boast good jobs, under its definition, report a high overall quality of life; among those with mediocre and bad jobs, that figure is 63 percent and 32 percent, respectively. This makes having a good job as important to overall well-being as health status.

The idea that the U.S. economy should provide all (or at least most) workers with well-paying, purposeful, enjoyable, secure jobs — which provide opportunities for advancement and some control over working conditions — may seem utopian. But the notion that working families shouldn’t need to accept usurious loans to make ends meet surely isn’t. And anyhow, in the “greatest economy” the world’s wealthiest country has ever seen, utopian working conditions are the least we should expect.