New York has finally decided that tossing troubled people into an antiquated dungeon, ensuring that they come out even more deeply wounded than when they went in, brings shame to a nominally civilized city. The isolated warren of cells, pens, yards, and trailers on Rikers Island — “a penal colony in the middle of the East River,” as council speaker Corey Johnson puts it — has been sentenced to close, part of a planned overhaul of the criminal-justice system that aims to halve the jail population by 2026. All of this seems hopeful, hugely expensive, and possibly quixotic.

The city is betting big on architecture. At the heart of the transformation is a plan to distribute detainees among four new high-rises, close to the courthouses of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. It will take an estimated seven years and nearly $9 billion to rehouse the equivalent of a small college’s student body into secure vertical dorms. That’s more than it will cost to rebuild LaGuardia airport, which serves 30 million passengers a year. These are optimistic uses of the future tense: Before the last ribbon is cut, those estimates will almost certainly come to seem quaint, shredded by delays, lawsuits, overruns, abuses, and waste. Meanwhile, nobody will want to spend serious money to rehab a doomed facility, and as the years go by, Rikers will decay ever more drastically, doing ever more damage along the way.

Around the country, law-and-order conservatives have insisted that the most effective way to clamp down on crime, fight drugs, and cope with extreme mental illness was to build more jails. Here, progressive politicians counter that the best way to reintegrate detainees into society, reduce the preposterous costs of keeping them locked up, dismantle the prison-industrial complex, and reap the dividend that comes with lower crime rates is to … build more jails. At the far end of the debate are No New Jails activists, who see incarceration as a perpetual instrument of racist oppression: You can’t design a more civilized detention facility, they say, any more than you can bludgeon someone gently.

Maybe a new generation of hyperexpensive confinement is truly the best or, at any rate, the unavoidable option. It’s certainly good to see politicians plan for a future that will arrive well after they’ve left office. But we should be skeptical about architecture’s ability to solve social problems on its own. So far, the de Blasio administration’s two-year-old strategy to reduce homelessness by building an archipelago of shelters has had no perceptible impact.

Or consider the precedent of public housing. In the second half of the 20th century, the powerful and well-intentioned decreed that the poor were living in irredeemable squalor; the only way to rescue them en masse was to tear down their neighborhoods and move them to modern, sanitary structures. For a while, it worked, especially in New York, where housing projects were generally sturdy, airy, and safe. It did not take long, though, for stinginess and prejudice to take hold. Light bulbs went unreplaced, elevators unrepaired, residents unheard. Drug dealers commandeered playgrounds and darkened stairwells, police stayed out, and parents kept their children away from open windows where they could be hit by stray bullets. The new solution for desperate poverty was to undo the previous solution: Authorities memorably dynamited the Pruitt–Igoe housing project in St. Louis in 1972, and more recently demolished the Cabrini–Green project in Chicago. The same logic held in London, when the council housing estate Robin Hood Gardens has come down over the last two years. These were failures of funding, politics, and social glue, but architecture was sold as the cure and so it got the blame.

For as long as there have been prisons full of abjection and despair, there have been plans to replace them with showcases of decency. London’s ancient house of horrors, Newgate Prison (a quick stroll from the courthouse, as New York’s new detention centers will be), had a demonic reputation, and it was demolished and rebuilt many times, only to revert to its old miseries. When one of those ever-more-modern iterations opened, it was soon overwhelmed by untreated mental illness. In his book London: The Biography, the historian Peter Ackroyd quotes an early-19th-century report on conditions at Newgate: “Lunatics ranged up and down the hallways, a terror to all they encountered.” The prison was definitively demolished at the turn of the 20th century.

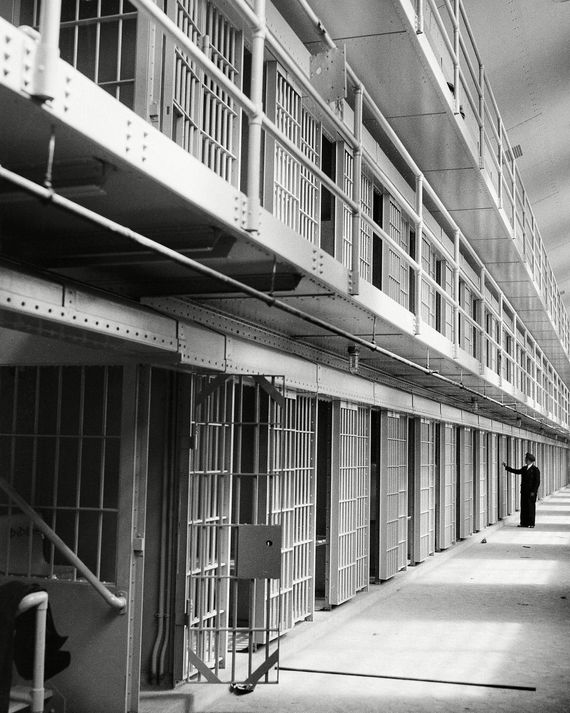

Rikers Island, too, began as an enlightened showcase. In 1886, when conditions (and porous security arrangements) in city jails like the Tombs horrified reformers, the city was already contemplating “an enormous model penitentiary, ample in size to serve for many years to come, and which … should be the most perfect prison in the world.” It took nearly 50 years before the offshore, purportedly escape-proof complex opened with a planned capacity of 2,200. Within seven years, the commissioner of corrections complained that he had no choice but to cram in 3,000 residents, using machine rooms for the overflow.

Crowding is a recurring theme in the history of correctional design. In New York, the jail population has fallen from a peak of 22,000 in 1991 to 7,000 today, and the goal is to get it to 3,300, the lowest number since 1920. Depending on whom you ask, that’s either too many or too few. Projecting that steep a drop assumes that the era of falling crime and compassionate corrections will stretch into the distant future. The city hopes to nudge the trend along by spending $391 million to transform the criminal-justice system from a bureaucracy of punishment into a social service agency, providing mental-health treatment, “violence interruption,” and various other programs meant to keep people out of jail. Not so fast, respond hardened pessimists: Crime can roar back at any moment, and when it does, we’re going to need somewhere to stash a surging population of criminals. Predictions follow politics, but crime may have a dynamic of its own.

Then there’s the question of what the city will be getting for its $9 billion. A well-ordered jail is not just a storage shed for human beings; it’s a place where defendants who have yet to face trial can prepare for their defense, keep busy, stay safe, and get ready for the outside world. Rikers keeps them focused on merely staying alive. There, moving prisoners around is a cumbersome proposition. Hallways can be treacherous, gates unwieldy. Every day, corrections officers load groups from Rikers onto buses and transport them to an assortment of courthouses and back. Lawyers have to set aside half a day to visit each client. Family members often can’t get there at all.

New jails can ease those transitions. James Krueger, a principal at the California-based architecture firm HMC, which designed the widely praised Las Colinas Women’s Detention Facility in San Diego, says that architecture can help flip the ratio of carrots to sticks. His firm designed six different levels of security within the same compound, with a goal of granting inmates as much autonomy as they can handle. “We want to incentivize good behavior through degrees of freedom,” Krueger says. “You can start out in level three and work your way down to level one, where you can walk to your classes and from one building to another without being escorted. You’re living on campus, but you need to be able to go for a walk and have a conversation with a friend or a counselor.”

Architects frequently beat the drum for the power of design to engineer society and improve lives. Those are not empty claims, but they should be tempered by modesty. One recent trend in hospitals and schools is evidence-based design, which translates data into some pretty common-sense techniques. Just the presence of a window improves patients’ health and students’ ability to learn. Old-style concrete-and-steel boxes amplify noise, pummeling detainees with constant, panic-inducing reverberations. New facilities can create a softer acoustic environment, giving bruised minds a chance to heal — and making it easier for officers to figure out where an anomalous noise is coming from.

Las Colinas, like most of the daylight-filled Scandinavian-style models that reform advocates promote, spreads out horizontally like a suburban high school. New York’s new jails will be towers surrounded by other towers, which makes getting detainees daylight and fresh air, for instance, a uniquely urban logistical puzzle. It also means building in costly redundancies, superwide stairwells, powerful ventilation systems, extra elevators, and outdoor spaces on almost every floor, which helps to explain the price tag.

“We use a ‘podular’ approach,” says Jeff Goodale, an architect who directs the Justice Group at the large firm HOK and who designed the startlingly airy Maple Street Correctional Facility in San Mateo, California. “You have 24 to 64 inmates in a unit and all the services they need — outdoor recreation, food, counseling, medication — are provided right there. That way, you’re not moving inmates throughout the facility.”

The far deeper challenge lies in alleviating a culture of brutality that can defeat any design. Architecture can express empathy; it can’t manufacture it. Goodale is bullish on design’s ability to improve behavior. “A third of the people who are in a facility every day are staff, and they may spend many years working there,” he points out. “If the space they’re in makes them feel less stressed, less burdened, and less overwhelmed, that has a positive impact on how they manage the inmates.” I hope he’s right, but I doubt that any building can force guards to treat their charges with respect if they’re inclined to see them as objects, or dissuade detainees from taking their frustrations out on each other. Eventually, any structure can fail under the weight of hostility and neglect, no matter how much it costs.

*A version of this article appears in the October 28, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!