Elizabeth Warren does not have a plan for this, and she’s in no hurry to develop one.

That’s mostly fine by the people around Joe Biden. Bernie Sanders’s braintrust understands, too. They’d just love to see her come to a decision soon.

Warren fielded calls from allies and rivals alike in the hours after Super Tuesday delivered her campaign a slate of bitterly disappointing results and questions about her political future took center stage. But none were as immediate as whether she would endorse one of the remaining two candidates for president. Sanders and Biden both spoke with her Wednesday, though it’s unclear whether either broached the matter — both have dropped out of presidential races themselves and faced agonizing decisions about what to do next, so understand the required sensitivity.

As Wednesday and then Thursday wore on, both campaigns sought to give Warren space and time, careful not to appear insensitive or desperate for her support. But around the country the race for her backing was on. On Capitol Hill, young House members supporting both Sanders and Biden reached out to their colleagues on Warren’s team, offering support and to talk whenever they were ready. (“I have a lot of respect for how the House endorsers generally conducted themselves,” said California congresswoman Katie Porter, who was a co-chair of Warren’s campaign.) Elsewhere, top Warren surrogates also saw their phones light up with calls and texts from backers of both campaigns. Sanders allies almost immediately got in touch with leaders of pro-Warren advocacy groups to gauge their interest in lining up behind him, with encouraging preliminary results. Other Sanders backers started talking about how to adopt some of Warren’s plans — a concept floated by California congressman Ro Khanna, one of Sanders’s campaign co-chairs, on MSNBC on Thursday evening. To get her support, one Democrat close to Warren advised, they should at the very least “take a page out of her book — it’s all about substance.”

But everyone, for now, is treading carefully, especially after a Tuesday night tweet from Minnesota congresswoman Ilhan Omar, a prominent Sanders backer, was read by Warren allies as blaming their candidate for Sanders’s losses. It’s a delicate topic, after all: A Reuters/Ipsos tracking poll out Thursday showed Warren’s supporters splitting evenly between backing Biden and Sanders — but Sanders needs all the help he can get after Biden’s recent surge has put the former vice-president in a dominant position.

For Warren, the calculus appears pretty straightforward: She could back Sanders, whose progressive politics are closest to her own; or, with Biden appearing to have the upper hand, she could probably make a higher bet by endorsing him, and use her resulting influence to help shape his campaign and, if he wins, his administration.

To those close to all three of them, the lessons of 2016 are instructive. In the leadup to that contest, Sanders made clear he wouldn’t run if Warren did — and then, when he ended up as the progressive standard-bearer, he set up multiple calls with Warren to ask for her support. But on those calls he never fully made the ask, finding it uncomfortable. That was around the time Biden decided not to enter that race, but only after informing Warren he wished to make her his running mate if he did run. Warren eventually decided to remain neutral in the primary until Hillary Clinton wrapped up the nomination, but she and her advisers felt stung by a backlash from Sanders supporters who accused her of betraying the progressive cause by not backing Sanders and then campaigning for Clinton. As Clinton approached the presidency, and considered Warren as a potential running mate, the senator made plans to shape the new administration’s appointments, drawing up lists of recommended hires and unacceptable nominees. If there was one thing that mattered to her, the senator’s team insisted, it was being able to influence the new White House’s policy — and, as she often said, personnel is policy. Now she’s faced with figuring out the most effective way to do that this time.

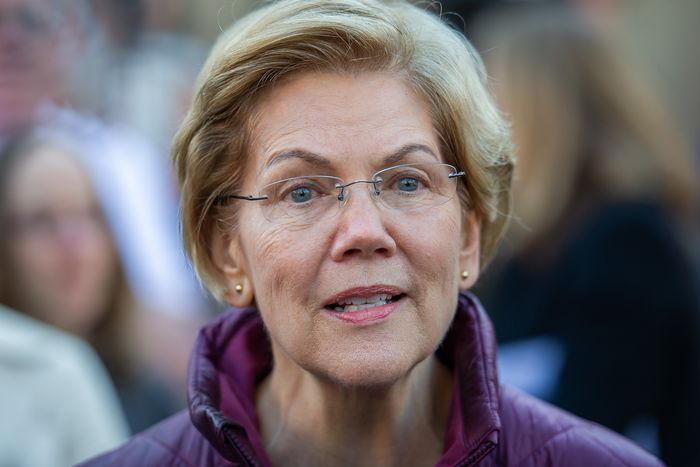

Warren, for one, has tried making it clear that she’s not necessarily in any hurry to make a move: “Not today, not today,” she told reporters outside her home in Cambridge after announcing her decision to leave the race on Thursday. “I need some space around this, and I want to take a little time to think a little more.” A few hours later, she told Rachel Maddow she had no timeline to decide.

Sanders’s team — divided between Washington, Burlington, and the campaign trail — has been watching Warren closely, eager for any signs about her thinking. Many suspect she is leaning toward Sanders over Biden, with whom she’s clashed, specifically over bankruptcy legislation in 2005. But whatever hope Sanders aides have about a Warren endorsement, they also fear time is running out: Sanders is desperate for a boost ahead of Tuesday’s primaries — especially the contest in Michigan, where he’s trying to prove he can do a better job of winning midwestern battleground voters than Biden. Until last week, Sanders’s team was generally more skeptical about endorsements, but the massive, shocking voter swing toward Biden in the wake of Pete Buttigieg’s and Amy Klobuchar’s decisions gave them pause. Now they’re hoping Warren can give Sanders a similar jolt.

Sanders, however, is hardly in a position to comfortably make this explicit case to Warren. The pair spoke only occasionally while they were both running, and after their debate-stage confrontation over their private January 2019 meeting, they only spoke at public events they both happened to be attending. Even communication between their top aides — some of whom had worked together in the past — diminished over the last few months.

Still, Sanders’s staffers have been thinking through how to make the case to Warren herself. One tactic they may avoid recommending: offering her some kind of job. For starters, that’s the kind of raw political maneuver that Sanders himself has been extremely hesitant to undertake over the course of his two campaigns. And, more importantly, they think there’s never been any doubt that Warren would play a major role in a Sanders administration anyway.

All of this adds up to a great deal of leverage for Warren. “The moderates [coalesced] and it proved extremely helpful. If she did it in a timely way, it could give Bernie momentum in the race, and could be huge,” said one senior Sanders adviser. “If Buttigieg and Klobuchar hadn’t [endorsed Biden], Bernie likely would’ve won seven or eight states [on Super Tuesday]. If progressives want to win, they’ve got to get together and unite. And she’s the one holding the keys.”

Biden’s team, meanwhile, is convinced Warren’s voters will split more or less equally between the two candidates in the short run. So his advisers see little reason to put significant pressure on her, given the strength of his position in the race. They feel confident heading into Tuesday’s contests — five primaries and a caucus — and believe they are on track for a resounding win in Florida the following week that could all but end the delegate fight. But they acknowledge that Warren would probably need more convincing to back Biden than Sanders, meaning an immediate nod toward the former VP is unlikely. If she backs him, many of them think, her timeline could look similar to the one she followed in 2016 — the endorsement likely wouldn’t come until it becomes clear that Biden will win, if it gets to that point.

But even behind closed doors, some of Biden’s advisers are quietly optimistic that Warren could, eventually, back him. In no small part that’s because much of her support was built around the kinds of highly educated white women who were central to Democrats’ sweeping 2018 wins — a group that Biden has courted heavily, and which has proven skeptical of Sanders. They also believe Warren’s calculus is likely different from the one most pols in her position might be working through, because her electoral future in Massachusetts, where she’s not up for reelection until 2024, might be less of a concern. “She doesn’t have to think about it in terms of, ‘Oh, I have to protect my progressive base.’ Everyone who thinks she wants to go and back Bernie, well, it depends on how much freedom she wants,” a top Biden adviser said. “Sometimes you can bring a progressive voice to the more moderate candidate in the race, and you can have a bigger impact.”

Yet back in Cambridge, Warren does not appear to be thinking like this quite yet. In the hours before announcing her decision to leave the race she spoke with a wide range of allies about the campaign.

Former Housing Secretary Julián Castro, one of her top surrogates, spoke with her on Wednesday. He echoed her in musing about how the race came back around to Biden versus Sanders — the moderate-versus-progressive battle a lot of people expected at the beginning of the process. “She put out a lot of the best plans that have been put out this entire campaign cycle, very visionary, forward looking,” he said. But now Warren allies are considering the same old set of questions, he said: “Can Bernie get beyond his core support? Can Biden consolidate everybody else? It does feel odd, like we’ve gone in a circle.”

Many of the people she spoke with urged her to take her time in determining what comes next.

“One of the things I affirmed to her is how important it is to me [to see] her make this decision for herself, in her own time, in her own way. When we’re talking about a field where there are no more remaining women, and the two remaining candidates are not people of color, it’s important to me that we see her own the power that comes with the incredible campaign that she ran, and to make that choice — even if the choice is to endorse neither — in her own way, in her own time,” said Porter. “I said to her, ‘If you call someone and the conversation is, You must, You have to, You should, You need, you should just hang up and call a different friend.’ She needs to really reflect on what she wants to do with the incredible support she brought about in her campaign,” Porter continued. “We trusted her to be our president, I’m certainly going to trust her to make this next choice.”

Most prominent Democrats in Warren’s broader orbit have yet to send signals about which way they’re leaning. Some have long been skeptical of Biden, but are disappointed with the Sanders campaign’s inability to expand upon the senator’s base, let alone the electorate. Much like her voters, Warren’s top supporters and surrogates say they are not necessarily going to follow her lead in backing one candidate or another, or remaining neutral.

Castro, for one, said he didn’t expect to make a decision in the coming days. And Porter laughed at the idea that she could be swayed soon, too. “Feel free, go ahead and pressure me,” she said. “Go ahead, take your best shot.”

The one thing they’re all confident Warren will do is remain active in the policy fights she promised to stick to. The challenge for her is identifying the most effective way to ensure that change happens. But that’s not just a question for the coming months. She has to consider the long run, too.

“There’s a lot of calculations to be made. Especially if she has any ambition in the future of doing this again,” said one person close to the campaign. Warren, after all, would be 74 in 2024. That’s three years younger than Biden is now, and four years younger than Sanders. “If we’re looking at a Trump, or a Biden, or a Bernie administration,” that person continued, “we’re probably looking at a four-year term.”

Castro said it outright: “She has a lot of options going forward. Including running for president again, if that’s what she wants to do.”