The co-host of a prominent right-wing podcast with Steve Bannon is raising concerns about the coronavirus on Twitter and warning that he may have been exposed to the disease. The culprit is not the liberal media, nor is it the deep state. Instead, it’s CPAC, the prominent conservative conference and right-wing pep rally held outside Washington, D.C., every year.

Raheem Kassam, a former aide to leading Brexit proponent Nigel Farage, turned his Twitter feed into an exercise in amateur epidemiology after CPAC announced that one attendee had tested positive for the coronavirus on Saturday. With a mix of sleuthing and conjecture, he tried to trace any exposure he and others might have had to the disease after he began experiencing flulike symptoms and news broke that five Republican members of Congress who were exposed at CPAC had gone into self-quarantine.

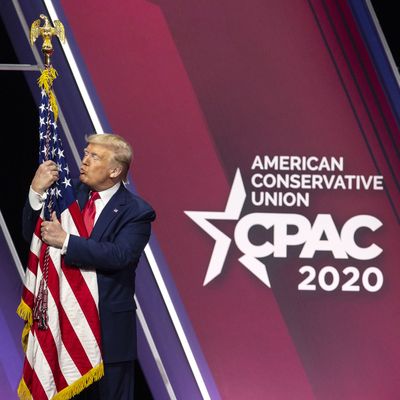

The annual conservative conference has continued to generate press in the week since it concluded, for being the potential ground zero of COVID-19 in and around the Capitol. There is abundant irony in that fact because the Trump-administration officials who spoke there minimized the impact of the coronavirus outbreak in general.

Mick Mulvaney, the outgoing acting White House chief of staff told he CPAC audience, “The reason you’re seeing so much attention to it today is that [media organizations] think this going to be what brings down the president.”

Kassam wrote, “I have been flu-sick unwell for the past week and now I am finding out there are people I was in direct contact with who were in direct contact with the infected.” The right-wing activist previously spoke at the conference and was featured in a video this year about Australia’s efforts to ban him from entering the country to speak at a CPAC event in that nation. In a series of tweets, he said that the infected attendee had gone to a CPAC Shabbat dinner and listed the possible VIPs who might have been exposed.

Kassam told New York that his tweetstorm was “not trying to cause a panic but to address a panic from attendees.” CPAC initially provided few details about the infected person. Instead, information trickled out through news stories about different dinners and receptions that the person attended.

Eventually, on Tuesday night, the American Conservative Union, the organization that hosts CPAC, sent out an email, saying, “The individual who tested positive for coronavirus did not go to the main ballroom, was not an interviewer or an interviewee on Broadcast Row, did not attend any breakout sessions and limited his interactions to very few people … We have tried to be clear about this, but to clear up any confusion: ANY individual who had direct contact with the individual who tested positive has been contacted in a one-on-one capacity.”

But some attendees were still feeling a lot of angst. In Kassam’s telling, roughly a dozen fellow CPAC conferencegoers, including those he described as “very high level” had called him over the weekend saying: “Please help us. We don’t know if we have touched this person.” The goal of his online efforts was to “give people some peace of mind, know if they needed to be quarantined, be tested, or take some Theraflu and chill.”

It’s easy to see how the disease could spread throughout the event. The conference sprawled over three floors of the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center just outside Washington, D.C., hosting thousands of people closely packed together. Many hands were shaken and certainly not all of them were appropriately sanitized. Attendees spent a lot of time standing in line, whether to be screened by the Secret Service before hearing an address from President Donald Trump or Vice-President Mike Pence or to buy $20 chicken-salad sandwiches. They swarmed D-list Trump celebrities like Sean Spicer and Sebastian Gorka for selfies, and at day’s end, they congregated for overpriced drinks and underwhelming gossip at the hotel’s two bars.

However, it seems patient zero missed most of these experiences at CPAC. He was a gold-level ticket holder. This meant he got to mix and mingle with VIPs and enjoy a private lounge in exchange for paying $5,750 to attend the event. It likely limited some of his interaction with the hoi polloi — college students in #MAGA hats and earnest, right-wing retirees. The result is that a disproportionate number of his interactions were with elected officials.

Attendees at that time were unconcerned about the pandemic. Alario Martinez, a volunteer for the event from Easton, Maryland, told New York he thought the disease was “a typical thing that always happens.” Samuel Garrett, a freshman at Regent University, simply said of the virus, “I don’t think it’s a legitimate concern for most people.”

Not all attendees are worried about potential exposure to the disease. Terry Schilling, a CPAC board member who runs the socially conservative American Principles Project, told New York, that he has thought the American Conservative Union “has done a good job in identifying this.” He has praised the organization for its communication effort and pointed a finger at “people who are panicking.”

Ian Walters, a spokesperson for the American Conservative Union, said that the group had identified “just over a dozen” people who had been exposed to the attendee with coronavirus, which included the public officials who had identified themselves on Twitter. He said that the organization was operating under the assumption that the patient — who has been in a hospital in New Jersey — was present for all four days of the conference. Walters pushed back at Twitter speculation about exposure. “Parlor games and trafficking in rumors is not helpful in the middle of what’s a public-health crisis.” Walters added, “Our decisions are being driven by operating in an abundance of caution.”

He told New York that Maryland public-health officials had performed a screening of 2,000 employees at the hotel complex where the event was held and that there were “zero cases of unusual illness.” The result was that the state said there was “no need for those employees to limit interaction.”

Walters said the organization was trying to be deliberate and notify all those with direct exposure to the infected person. With “direct exposure” he said: “The responsibility really does rest with us. What Maryland deals with is those who are symptomatic.”

It’s possible no one was infected with the coronavirus at CPAC. It’s possible that dozens of people were. Responsibility doesn’t lie with anyone in particular for whatever happened. It just happened to be a large conference of people from across the country that occurred at just the right time as the pandemic reached the United States. It could have as likely attracted insurance agents as Matt Gaetz, the now-quarantined member of Congress who wore a gas mask on the House floor just to troll last week. (Gaetz, who had flown on Air Force One just hours before going into self-quarantine, announced Tuesday that he had tested negative.)

But there is no manual to deal with this, no playbook in a world that was previously a century removed from a pandemic like this. Elected officials in European countries like France and Italy have tested positive for the disease; senior government officials in Iran have died from it. The CPAC exposures just represent the first major impact of the virus on the American political system.

As Gaetz said to reporters last week, “Members of Congress are human petri dishes. We fly through the dirtiest airports. We touch everyone we meet.” Proof of that came sooner than he might have guessed.

Kassam is currently in quarantine awaiting the results of his coronavirus test. As he pointedly noted on Twitter, he was shaking hands and talking to Congressman Paul Gosar just one hour after the Arizona Republican spent “an extended period of time” with the infected attendee.