The White House briefing room is a low-ceilinged claustrophobic space. Built on top of a swimming pool where Franklin Delano Roosevelt exercised and John F. Kennedy canoodled, the room has 49 chairs set into the floor where reporters once packed in for daily news conferences while trying to avoid tripping over the camera equipment strewn about the narrow space. These days, only 14 of them are occupied.

These days, the White House is almost certainly is the weirdest beat in American journalism. Reporters who show up at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue get addressed by the president of the United States at length almost every day. Trump also takes questions from the press almost to the point of exhaustion. Sometimes, he even answers them directly. It’s the most access any president has given the media in modern times. And all reporters have to do to get a chance to participate is risk their health and that of their family.

Jonathan Karl, the president of the White House Correspondents’ Association, told Intelligencer that the pandemic presents “a tremendous challenge.”

“We are trying to limit the number of people who go to the White House … Right now if you go to the briefing room and to the press area, you see it’s a hell of a lot emptier than it usually is, and that’s a good thing,” he said. Karl, the chief White House correspondent for ABC and author of the new book Front Row at the Trump Show, added that “the challenge is that this is also the biggest story of our lifetime and the instinct of every reporter is to want to be there. But fortunately people understand that not only is it dangerous to have too many people there but it ultimately would impair our ability to cover the story if we can’t do it safely.”

In addition to limiting numbers, reporters have been required to have their temperatures checked before entering the briefing room and even had to take tests for the virus before Thursday’s briefing. Yet even those precautions are only a starting point for those journalists who still go to the White House. In talking to dozen reporters who regularly cover the White House, most of whom spoke on background in order to speak candidly, they all spoke of their own routines to stay safe, which invariably include liberal doses of hand sanitizer. As one described it, “I brought Clorox wipes and wiped the seat, the armrests, the seats in front and behind … and brought paper towels so I didn’t have to touch the door to enter the White House.”

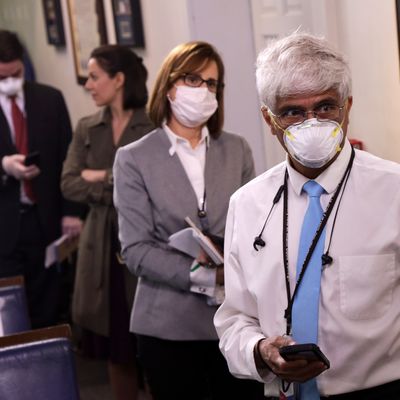

While no reporter has worn a mask during a briefing, some, who have yet to muster the courage to wear one on live television, have contemplated it. “At some point, it is going to be a necessity for everyone in that briefing room to be wearing masks,” one reporter acknowledged. (As seen in the photo above, masks are a common sight when the cameras are off, as well as among photographers and producers.)

Reporters know that showing up to the White House is not equivalent to “embedding in Fallujah,” as one said, but the risk is also different because it endangers not just them, but their families. “If I decide to cover a war or a violent protest, I’m putting my ass on the line,” one reporter said. “I’m not charging into a riot with my wife, though.”

Some reporters are more blasé about the risks than others. One White House reporter told Intelligencer that he had stopped going after seeing “a significant number of White House reporters, mainly younger and working for right-wing websites, not taking it seriously.”

The one person to flaunt WHCA policy has been Chanel Rion, a conspiracy theorist who appears on the small conservative cable channel One America News Network (OAN). Rion has shown up on days when it was not her turn to participate, claiming to have an invitation to attend the briefing from outgoing White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham. After Rion violated social-distancing guidelines by repeatedly standing in the back of the room, the WHCA stripped OAN of its seat in the briefing room — as harsh a penalty as it can impose. Other reporters mostly shrugged off her antics as “performative” and a PR stunt.

It’s possible that more extreme steps will be taken. One reporter noted that he was originally taken aback when the number of people allowed in the briefing room was reduced to 14. “That seemed very skeletal and exclusionary,” said the reporter. “But the more I have been in there as the crisis has played out, 14 is claustrophobic. You are not six feet from the nearest person, and even though it is like a slow Sunday afternoon in terms of the number of people there … it still feels like, ‘Wow, this is a lot more people than I want to be around.’”

Meanwhile, some in the press corps are welcoming the opportunity to be at the White House. One reporter said that he was going “every chance I get” and was scrambling to pick up opportunities to be a pool reporter when other outlets blanched at the risk of infection. “I’m less worried about my health and more worried about missing the opportunity to do good work,” he said. Another more health-conscious reporter acknowledged, “I’ve gotten more answers from the president than I’ve ever gotten before. The odds have dramatically improved.”

While the WHCA has worked with the White House press office and kept them in the loop on the press-pool changes, it has been a delicate process. After all, the group is a voluntary organization with no official authority. Its leaders are full-time journalists with day jobs reporting on the administration. Their primary goal throughout the pandemic has been to ensure that there is always a protective pool, the rotating group of reporters who stick closely to the president and follow his whereabouts, and that there are sufficient reporters healthy enough to do maintain that function.

One White House reporter noted that the WHCA has limited options, particularly in an administration that has taken as adversarial a tone toward the press as Trump’s.

“I think the WHCA is trying, but what the hell are they going to do?” said the reporter. “If they propose moving the briefings, then the White House would commandeer that space and we would never get it back … it’s valuable space. If you go to a conference call they would mute the line and call on friendly reporters. If you go to the Rose Garden, it gets cold a lot of days. There are not a lot of things to do.”

The WHCA also has to be careful not to venture into advocacy on any of these options. After all, holding a daily press briefing with the president in the briefing room isn’t just about the reporters there. It’s a policy decision by the White House about what message it wants to communicate to the country.

The briefings themselves have changed reporters’ jobs dramatically. After going a year without a single press briefing from the White House press secretary, Trump is now opining for hours at a time. Peter Baker, a veteran White House correspondent for the New York Times, who has covered the White House since 1996, said, “I’ve never seen anything like this where the president comes out every single day, not just for half hour, not just an hour, sometimes two hours on-camera.”

It’s also changed the rhythm of the work day. Traditionally, White House press secretaries held briefings in the afternoon. Now the president emerges sometime after 5 p.m. every day. It’s perfectly timed for evening news but presents hazards for print deadlines and those working conventional hours — not that anyone is complaining. “People are dying,” said one reporter. “We can work a little later”

Reporters remain mostly enthusiastic about the value of the briefing. “It’s absolutely useful,” said one. “People need to hear directly from the president during this and we have to hold him accountable for decisions that he has made so far. What’s just as important as hearing from him is [hearing from] Fauci, Birx, Pence, and that kind of access is critical and I commend them for doing this every day.”

“Even if a portion is dedicated to delivering a political briefing, it’s not the whole thing,” the reported added.

A number of outlets, including the Washington Post and the New York Times, have nonetheless stopped attending because of health concerns. After all, reporters can watch a televised briefing at home and avoid any risk of contagion.

While understanding the calculus that prompted outlets not to show up, one White House reporter expressed angst about who would be left if other news organizations stopped attending, explaining, “I’d hate to see the briefing room stocked with reporters with Fox News, the Daily Caller, and OAN.”

Veteran political reporters struggled to compare it to anything else. Most frequently, it was likened to the terrorist attacks of September 11 and its aftermath, only somehow more terrifying. As Baker noted, “After 9/11, people were afraid to go in [the White House] because of terrorism. At least then you weren’t afraid of the people standing next to you.”

In some ways, other than the magnitude of the coronavirus story and the new ubiquity of the briefings, much of the day-to-day routine hasn’t changed. White House reporters often spend much of their time on the phone or texting with sources rather than engaging with people face-to-face. Unlike on Capitol Hill, reporters can’t roam freely around the White House, so they spend less time interacting personally with top officials. In some ways, though, the virus has made reporting on the presidency less challenging. “Everybody is at home so its actually in some cases easier to get a hold of [sources],” said one reporter. However, it does limit source development, which another reporter noted is “far harder to do when you can’t meet people in person.” As a third White House correspondent pointed out, “You get less out of people over the phone than over a drink.”

But reporters do sense sources have different agendas than in the past. One reporter noted that during the dramatic peak of the administration’s infighting in 2017, sources were “motivated by pure malice, personal hatred, and revenge.” Now, “everyone is trying to cover their ass for history.” The rules of the game are similar but the stakes are not, another White House reporter pointed out: “The desire to set the record straight and get their side of the story out is not about how it will be perceived [in Beltway tip sheets], but when books are written and autopsies chronicled, how they will be remembered.”

The law of averages suggests that eventually a White House reporter will test positive for the virus. So far, tests in two suspected cases have come back negative, while a third reporter, who has been suffering symptoms for two weeks, has yet to be tested. When that happens, it will likely force even more changes. In the meantime, the briefings will continue, Trump will keep showing up and holding forth, and reporters just have to hope they’ve stockpiled enough Purell and disinfecting wipes to make it through the pandemic.