On Friday, House Democrats will vote on a $3 trillion coronavirus stimulus package that the caucus widely describes as a messaging bill: Nancy Pelosi knows her Republican colleagues aren’t going to consent to a package of reforms as progressive and far-reaching as the one her colleagues just assembled. The point of the legislation is to show the American people what Democrats would like to do for them and establish priorities heading into negotiations.

The bill has many laudable provisions. But it also suffers from baffling omissions. Chief among them, the absence of any proposal for what we in the wonk business call “automatic stabilizers.”

An automatic stabilizer is (more or less) any fiscal policy that mitigates the severity of an economic downturn without Congress having to take any new action. Medicaid and food stamps are two prime examples: When the economy weakens, the number of people who qualify for public health insurance and food assistance goes up, and spending on those programs automatically increases in response. This helps to (modestly) stabilize household incomes and demand for groceries and medical services. Unemployment benefits serve a similar function.

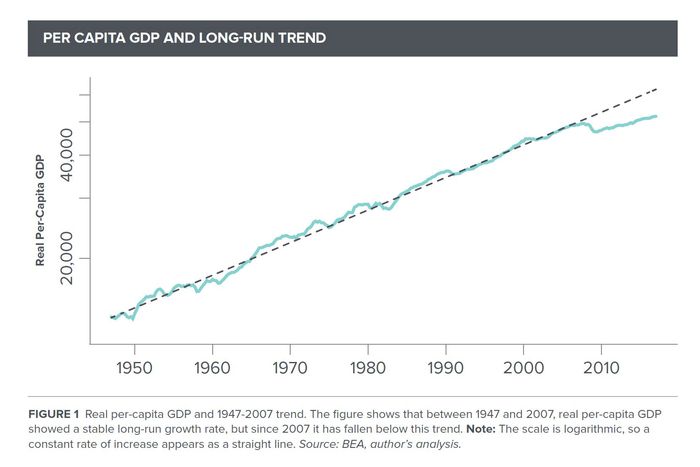

In the years following the financial crisis, economists developed a keener appreciation for the value of such stabilizers — in part because they developed a clearer understanding of the harms of deep recessions. In the decade following the 2008 crash, the U.S. economy never caught up with its pre-crisis productive potential; millions of workers who lost their job to the crisis never reentered the labor force.

Previously, economists had viewed stabilizers as means of easing the human costs of slumps and accelerating the revival of consumer demand. But the lackluster post-2008 recovery made clear that any policy that shortens a recession also serves to increase long-run growth. This fact — combined with the U.S. Congress’s perpetual struggles to pass legislation in a timely manner — has produced widespread support among (non-right-wing) economists for establishing a variety of new, robust automatic stabilizers to both preempt and mitigate recessions. One such idea would be to have the U.S. government automatically mail every American a $1,000 check whenever the U.S. unemployment rate falls below exceeds a certain threshold.

Tying stimulus measures to such triggers is good policy in the abstract. And it’s absolutely vital in the present context. Republicans have agreed to provide some fiscal aid to ordinary people in recent months. But now that equity values have recovered somewhat from their March collapse, the GOP’s appetite for such measures is already waning. Enhanced unemployment benefits are set to phase out in July, and Republicans are adamant that they will not renew the program. Had Democrats insisted on making those benefits activate automatically whenever unemployment is high — instead of having them switch off on an arbitrary date — America’s workers would be far more secure than they are today.

Meanwhile, if the GOP is unwilling to provide sustained aid to the unemployed when a Republican is in the White House, they are all but certain to obstruct further stimulus under a hypothetical President Joe Biden. If Democrats want to prevent McConnell from sabotaging the economy in 2021 (as he did throughout the Obama years), fighting to make any existing stimulus automatic is likely their best bet.

And yet, when sitting down to construct a partisan wishlist for the next stimulus bill, Pelosi did not include a single proposal for stabilizers — despite the fact that such policies had strong support from both moderate and progressive Democrats.

Here’s why:

Speaker Nancy Pelosi had publicly endorsed the concept of using automatic stabilizers last week but ultimately decided not to include them in the bill because of the cost. [Virginia representative Donald] Beyer said Pelosi communicated to the caucus that the way the Congressional Budget Office scored stabilizers would have added “an enormous price tag” to the bill.

“It just became really difficult for her to go to the public and say, ‘Here’s a bill for $4 or $5 trillion,’” he said, noting he respects her decision not to move forward with the proposal.

This is baffling on multiple levels. Democrats’ fear of large numbers has always been irrational; if literally balancing the federal budget didn’t stop Republicans from branding the party as spendthrift liberals, pinching pennies in a recession isn’t going to do the trick. And concerns about appearing fiscally reckless are especially mindless at a time when the Republican chairman of the Federal Reserve is publicly arguing that now is “not the time” to worry about deficits. But even if it were rational for Democrats to worry about looking fiscally irresponsible, whom exactly is Pelosi trying to placate? What voter considers a $3 trillion stimulus bill to be eminently reasonable — but finds the idea of a $4 trillion stimulus outrageous? How is the distinction between those two numbers intelligible to an ordinary person? Yes, $1 trillion is in actual fact a lot of money. But this is a messaging bill. And in messaging terms, “$3 trillion” and “$4 trillion” both translate to “an unfathomably large number of dollars.”

Separately, whatever the CBO’s model suggests, well-designed stabilizers should at least partly pay for themselves in the long run by shortening recessions and thus conserving the economy’s productive capacity. To the extent that stabilizers are expensive in the near-term, that is a reflection of just how many needy people such policies would help.

Pelosi may have been averse to including every worthwhile Democratic idea in this week’s bill, so as to set clear priorities. But prioritizing expert-tested, moderate-approved measures — that will likely be necessary for preventing Republicans from sabotaging the next Democratic presidency — should be a no-brainer at any price.