On April 3, I became a doctor while sitting at my dining-room table. My graduation from NYU Grossman School of Medicine had the outlines of normalcy. Our deans and mentor physicians spoke to the exceptionalism of the noble occupation we had chosen. They praised our brilliance, kindness, and, most of all, our professionalism. And yet, of course, this graduation — held over Webex nearly two months ahead of schedule, without the spectacle of caps and gowns — was anything but normal. Just ten days earlier, I had received an email from my deans at NYU that asked me and my 122 classmates to voluntarily graduate early and join the workforce in the fight against COVID-19. If I accepted, I’d start my career as a physician two weeks later in either NYU’s internal-medicine or emergency-medicine residency programs.

NYU was the first school in the United States to ask its senior students to graduate early. At least ten other U.S. medical schools would follow. There is historical precedent for this decision. In 1918, with many medical providers overseas fighting in World War I and the Spanish flu raging through the United States, medical students were asked to join the workforce. The move has some precedent within the COVID-19 pandemic, too. Junior doctors in Italy and the U.K. were recruited to the front lines as hospitals in Europe were overwhelmed with sick patients.

My classmates were divided on whether to volunteer. Many insisted that it was our time to help. Others, including me, had reservations. I had been following the onslaught of bad news about our government’s failure to respond to the pandemic, leading to shortages in personal protective equipment (PPE) and other essential equipment. I had seen stories about young health-care workers dying across the world. Was I supposed to march into the hospital without hesitation? I was struck by a discomfiting grief — the burden of duty to society, myself, my peers, and my loved ones pulling me in all directions. Unexpectedly, once I resolved to graduate early, my mind settled. The decision did not feel heroic or courageous. Instead, I found the idea of remaining in social isolation while knowing I could help more agonizing than the — still terrifying — idea of willingly entering the hospital during a global pandemic.

In the end, 52 members of our class signed up for early graduation. Our entrance into the ranks of physicians was sealed by a reading of the Hippocratic oath. Each of us was asked to unmute our computer’s microphone and read together. The result was a beautiful mess. A cacophony of sentence fragments, echoing each other like a song sung in rounds: “that I will be loyal to the profession of medicine”; “that I will be loyal to the profession of medicine”; “that I will be loyal to the profession of medicine”; “for the good of the sick to my utmost power”; “for the good of the sick to my utmost power”; “for the good of the sick to my utmost power.” Each phrase spoke to the pressing duty of today while also binding us to the millennia of physicians who have shared in this code.

Two days later, I began my weeklong hospital orientation. I would be working as a resident in internal medicine at Bellevue Hospital, the site of most of my clinical training in medical school. But in the intervening weeks, the hospital had been transformed to accommodate more than 1,100 COVID-19 patients, its resources and manpower stretched thin in the process. Bellevue is the oldest public hospital in the United States. Its history is intertwined with the history of modern pandemics, from yellow fever and tuberculosis to AIDS and Ebola. As a public hospital, it is also responsible for taking care of the uninsured and undocumented — patients who have been shown to be disproportionately at risk for poor outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

I was reminded by multiple stern and weary doctors who trained at Bellevue during the heart of the AIDS epidemic that COVID-19 has been unlike anything they have seen before. It was unclear whether this was meant to chasten us or galvanize us.

How does one prepare to enter a fight against a global pandemic? If I squinted as I watched HR videos about workplace harassment and fire precautions, I could almost convince myself this was all normal. Other parts of the training brought the current pandemic into relief. When I was first taught how to wear PPE two years earlier as I was starting clinical clerkships, I half listened; I figured I would learn on the job. Now, I watched the trainer intently as he explained the proper etiquette for taking on and off the N95 face mask, eye shield, gown, and gloves. The steps seemed much more intricate now that failing to follow them could have such dire consequences. The trainer showed me how to lean forward at the proper angle to take my eye shield and gown off without soiling my N95 face mask. I imagined virus particles were all around me as I practiced with a long-sleeved shirt instead of medical gowns because of anticipated shortages in PPE. I asked questions that would’ve sounded ridiculous a month ago: Should I strip naked before entering my apartment after a day at work? Though the official answer was no, I resolved I would anyway.

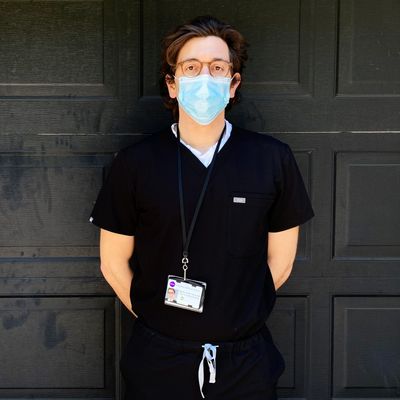

The next Monday, as I put on my scrubs and mask for my first day of work, I was propelled by anxiety and excitement. I had worked ten years and countless hours for this moment: the first time I’d be entering the hospital as an M.D. It was pouring rain in New York, and though it’s only a five-minute walk from my apartment to Bellevue Hospital, I was drenched by the time I walked in the front entrance and toward the newly established temperature-screening point. I was surprised at how familiar the wards felt when I got off the elevator. The same cold fluorescent lights. The same smells, acrid and organic. That every face here was concealed in a mask was somehow not as unsettling as it had been in Trader Joe’s. It was the sounds that oriented me most: beeping, everywhere. The language of the hospital is beeps — the oxygen is too low, the heart rate is normal, the medicine has been given. Almost every action in a hospital has a corresponding beep.

The superficial familiarity, however, concealed profound difference. As I became acquainted with “my list” — the patients my team was assigned to care for — I learned that every one of them had COVID-19. My list was not an anomaly; nearly every patient in the hospital had the coronavirus. Whole floors once dedicated to surgical specialties, cancer, and heart failure had been turned into COVID overflow floors. The idea of specialists, at least temporarily, no longer existed; nearly every provider in the hospital cared for COVID patients.

The providers themselves were different too. Many were traveling nurses, NPs, and PAs — reinforcements flown in from across the country. Some were meant to serve at the Javits Center and other “relief valve” sites, but, at least by their own reports, so few patients were making it there that their assignments had been changed. An NP from Memphis told me in a southern twang: “Every year, I go on a service trip to a different place. Last year, I went to Nicaragua. Year before that, Ghana. This year, I’m here helping y’all.” The implied comparison unsettled me.

Before I started, I had become increasingly obsessed with numbers. Case fatality rates and infectivity scores and flattening curves. If I could just grasp the facts and figures, wouldn’t I get some semblance of control? But on my first day, as I rounded with my team on critical patient after critical patient, the statistical lens through which I’d seen COVID dissolved. The numbers were now real human beings whose health I was responsible for. That first day, I counted at least 20 “RRTs,” or rapid responses, announced over the hospital PA system. Each time the PA system beeped overhead, I prayed it was not my patient who needed to be ventilated and brought to the ICU. Wouldn’t it represent some personal failure if it was?

My attending and older residents assured me there was very little we could do to halt the natural progression of COVID-19. Patients either got better or worse; our efforts made almost no difference. But my education had cemented a clear conviction: medical interventions make sick patients better. I stubbornly clung to the notion that a patient improving was a result of our successes, and a patient deteriorating the result of our failures. What was the point of all this schooling if my role was merely to watch and wait?

Lying in bed after my first day, I felt haggard, burdened by the enormity of responsibility and how little I could actually do. As I was about to fall asleep, a beep came over my cell phone — the resident Slack channel announcing another rapid response, this time on a 33-year-old critical patient I was caring for. I felt queasy. Powerless in my bed at home, I already couldn’t escape the hospital.

The next day, a patient unexpectedly died. I was eating lunch when a “code” — indicating the patient was without a pulse — was called to her room. I thought it was a mistake as I ran up the stairs. She had been the patient I was least worried about; just hours earlier, we had discussed the possibility of her going home soon. Now I was outside her room, frantic as I peered in through the double glass doors and saw an older physician I did not recognize doing chest compressions. I had been told that the recent graduates would not be part of codes, since there is a high risk of viral transmission during these “aerosolizing” events. But how could I not enter? I put on my PPE and stood there frozen, staring into the room, literally and figuratively at the precipice between student and doctor. The patient was pronounced dead before I could make up my mind to enter.

The hospital has been a lonely place for patient and provider alike. With patients wearing oxygen masks and providers covered head-to-toe in PPE, the ability to have real conversations has been difficult. Most of the patients on my team spend the majority of their days completely alone, without any form of distraction. But amid the isolation, the hospital has still had moments of genuine human connection and joy. One of my patients was desperate to meet her newborn grandson, so I found a donated iPad and held it for her as she FaceTimed with her daughter and the baby. She smiled at me through tears when the call ended. “That beautiful boy, he has a whole big life to lead,” she said. “I just pray to live another day.”

Toward the end of my first week, as I prepared to leave after another long day, the hospital intercom beeped. I feared it was another RRT. Instead, Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” began to play over the Bellevue PA system. The hospital seemed to pause. Whispers had circulated that the song would be played hospitalwide each time a patient was extubated or discharged from the ICU; I had yet to hear it. Relief flashed across everyone’s eyes — a big, collective exhale. Some nurses began to clap to the rhythm. I was surprised to find myself laughing.

These moments of levity, however, have been few. Five of the first ten patients I cared for passed away. For a new physician — for anyone, really — this amount of death is disturbing. I remember the names and faces of each of them; their deaths will no doubt stay with me. In my two years of clinical experience as a medical student, I had lost four patients total. I was shocked the first time family members looked to me for consolation and wisdom as their loved one neared death. Certainly, they thought, as I felt, that I was just a random guy who had taken a couple of science classes and was given a stethoscope and a white coat.

Over the course of medical school, my impostor syndrome diminished. I came to appreciate my role in those critical moments before and after death helping a family come to terms with the inevitable — to begin to grieve and, ultimately, heal. But COVID has uniquely undermined this critical aspect of patient and family care. Given the sheer volume of patients and the acuity of each case, I’ve had less time and emotional bandwidth to process my patients’ deaths. One afternoon, I received a call from a patient’s daughter, who was sobbing as she told me that her mom had passed away and she was trying to locate her belongings. I was ashamed that I didn’t initially recognize the woman, or which patient she was talking about. Finally, I realized that it was the new grandmother, the one I’d found the iPad for. She had passed away, alone, after a week of being on a ventilator in the ICU. Before I could internalize this, my pager beeped with another urgent task for me to attend to.

The NYU residency program and my mentor physicians have done their best to make space for processing what we’re going through. There are regular debriefing and group-therapy sessions that help, but none of that can change what we’re witnessing daily. The first years of residency are known as particularly formative in a doctor’s career since our medical habits and “muscle-memory” have not yet been cemented. This experience will inevitably shape the kind of doctor I become.

Even over this first month of being an M.D., I have noticed a new hypervigilance take hold of me. My first night shift in the hospital, I was assigned a patient whom the primary day team described as “stably sick.” When I went to introduce myself, I found him delirious in the midst of pulling off his oxygen mask. I watched in horror as his oxygen saturations dipped from 95 to 48 in a matter of seconds — anything less than 90 is too low, and I had never seen a conscious person lower than 70. I ran out of the room to call an RRT. Even as the patient stabilized, I could not relax. Each hour for the rest of the night, I found myself back at his door, peering in through the acrylic window to check his oxygen saturation.

This hyperalertness has lasted. In medical school, I was taught that a patient’s medical trajectory is typically relatively easy to track. Though occasionally physicians are surprised by their patients’ outcomes, most of the time they follow a predictable course. My experience with COVID patients has shattered that belief. So instead, I find myself constantly on high alert. That hypervigilance is a cardinal symptom of PTSD is not lost on me.

Things have, thankfully, begun to normalize in the hospital. With far fewer COVID patients coming in each day, I have had time to wonder whether I would make the choice to graduate early again. I think the answer is yes, but I sometimes wonder if it’s some sort of masochism that’s driving me or, worse, an unconscious desire to be the hero. I am grateful that my initial worry about getting sick myself, or infecting loved ones, hasn’t come to pass. But that reservation has been replaced with new doubts. The truth is I’m not sure how much I really did for my COVID patients — or how much I could have done, even if I were a far more experienced and talented physician– beyond offering some kindness in their final days.

I am certain of one positive that’s come from this: Each day was a reminder that we physicians have no superpowers; that we know far less than we need to; and that, despite all this, we must persist and find comfort in this uncertainty. I have been told that humility for our professional capabilities takes some doctors years to learn, but in these few weeks, I have been forced to come to terms with medicine’s limitations.