One of the clearest signs of how much has changed over the past several months is how critiques of government that may have recently been about corruption or excess are now often about what looks like an inability to provide even basic help in a time of desperate, everyday need. A bungled health crisis has been followed by a mishandled lockdown that fell far short of its promises and cost millions of people their livelihoods, open violence from law enforcement, and huge numbers of citizens taking to the streets. “The city, the government, they have forgotten us,” a Bronx resident recently told the Times.

“People who have never interacted with the government are reaching out for help and feeling shame, feeling embarrassed — and the volume only increasing, and increasing, and increasing,” New York state senator Alessandra Biaggi said recently. Biaggi won her seat in 2018, part of a progressive surge that defeated a slate of centrist members of her own party and moved the power of the legislature to the left. Last November Biaggi endorsed Eliot Engel, the 16-term incumbent in the House of Representatives whose seat contains part of her district. “At the end of 2019, I took a pretty firm stand that this was not the year to primary Democrats. We had a very important presidential race coming up, perhaps the most important of our lifetimes, and my focus was going to be on that,” she said. She does not feel that way anymore. “Since then, the world has changed.”

Earlier this month, Biaggi retracted her endorsement of Engel and threw her support behind his main primary challenger, Jamaal Bowman. “You look around and you wonder who is speaking out against these things,” she said. “And the number of people who have remained silent is alarming. It’s alarming!” Bowman had been endorsed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and has since earned endorsements from Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and the New York Times, which dryly noted that though Engel has been in Congress since 1989, his “connections to the district seem to have frayed.” Michelle Goldberg, a Times columnist, recently wrote an op-ed titled, “Can Jamaal Bowman Be the Next AOC?” From April to June, Bowman’s campaign raised more money than Engel’s — an astonishing achievement for a primary challenger, and something even Ocasio-Cortez failed to do in her upstart campaign against incumbent Joe Crowley two years ago — and this week, a poll from Data for Progress has Bowman with a ten-point lead. Moving forward, Biaggi said, “We are going to need people who feel the pain of others.”

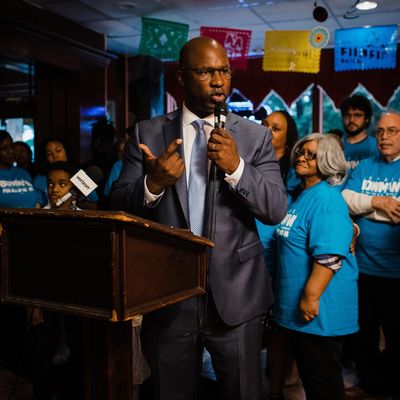

Bowman, 44, shaves his head bald and has the broad shoulders of an ex-athlete. He’s quick to note when something makes him excited, or sad, or angry, and wears his emotions close to the surface. He grew up in Manhattan, living with his grandmother in NYCHA’s East River Houses until he was 8. He then moved in with his three sisters and his mother, a clerk for the postal service, in Yorkville, and now lives in Yonkers with his wife and three children. For the past 20 years, Bowman held a handful of positions in New York public schools: He taught elementary and high school in the Bronx, and worked as a high-school dean. “A lot of people don’t see how success in school is connected to health care, how it’s connected to housing, even how it’s connected to overall public health,” he says. “Children don’t struggle in school by accident.” In 2009, he founded a Bronx public middle school, Cornerstone Academy for Social Action, because he found that a decade into a career as a teacher and a counselor, “I often felt more like a correctional officer than an educator.” Two of his first hires were the school’s guidance counselor and its social worker.

He laughs easily, and volunteers personal details where other politicians, or other school principals, might be more withholding. “When I was in school, I didn’t have the best grades,” he recently told a voter from Edenwald whose son had trouble in school. “It wasn’t because I wasn’t intelligent. It was because I wasn’t engaged.” As a child, Bowman had a difficult relationship with his father, and says, “I started to act out as a kid, with my friends. Because I was so angry — I didn’t know how to manage that emotion.

“I had family members who were addicted to drugs, friends who were murdered, who committed suicide, friends who were incarcerated. I had friends who went too far — they didn’t have an outlet to channel their rage and their anger and their depression. But someone introduced me to sports, and the arts, and music, and it gave me a space to harness my anger and frustration in a positive direction.” He finished high school in New Jersey, where he was an all-state defensive tackle. “If I didn’t get the chance to play high school and college football,” he says, “I would’ve never graduated college, I would’ve never become a teacher, and I wouldn’t be here today.”

The 16th Congressional District has been a bellwether of New York’s coronavirus crisis: It contained the state’s first major outbreak (in New Rochelle), some of its starkest disparities in testing and PPE (the district extends from the Bronx into Westchester), and has been hit as hard by the pandemic as any congressional district in the country. Bowman, a resident of 16th, is running on a campaign of racial and economic justice. He recently announced a slate of reforms that call for a Third Reconstruction, building on the work that followed the Civil War and, a century later, the fight against de jure segregation. “Each step forward was met with a backlash,” he says. Civil rights and legal protections ran up against “dog-whistle racism, mass incarceration, and a gutting of public programs.” In addition to the standard progressive support for Medicare for All and a Green New Deal, this would include removing funding and military equipment from police departments, federal support for social services and nonviolent conflict resolution, and a national truth and reconciliation commission tasked with an accounting of the role of the federal government in the country’s long history of racism.

Engel, the incumbent in 16th, is the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and hasn’t had a serious primary challenge in 20 years. In May, The Atlantic reported that Engel hadn’t visited his district “since at least the end of March” — nearly the entire stretch of the pandemic. (For at least a decade of Engel’s time in Congress, he listed a house in Maryland as his primary residence.) Bowman has put together a team of staffers and supporters from the past campaigns of Biaggi, Ocasio-Cortez, and other members of the post-Trump progressive wave. Before the month was out, the New York Post warned that Engel was “setting himself up to be the next Joe Crowley.”

Bowman starts his day around 5 a.m., exchanging texts with Rebecca Katz, a campaign adviser, before his kids wake up. “We run through the news of the day — run through Twitter, run through the New York Times, collect our ideas on how to approach what’s happening in the campaign or the country,” Bowman says. Sometimes he’ll also send early texts to Luke Hayes, his campaign manager, who doesn’t have children. “But Luke doesn’t respond for like three hours. He says he doesn’t have ‘parents brain.’ And, you know, when you’re a middle-school principal, you’re on that kind of clock anyway.”

The coronavirus crisis didn’t change just what voters want out of a candidate; it cut off most of the conventional ways that progressive campaigns engage the members of their districts. “So much of campaigning, especially for local campaigns or challenge campaigns, is showing up,” says Hayes, a veteran organizer and campaign manager who also ran Biaggi’s campaign in 2018. “It’s community meetings in basements, going by a school drop-off and meeting parents, shaking hands at a subway station for morning rush hour.” Ocasio-Cortez beat Crowley with a campaign of shoe leather and door-to-door engagement. When New York began sheltering at home, Hayes says, most of that “went out the window.” But the basic question a campaign has to answer has stayed the same: “Where can we meet the voters?” These days, even Joe Biden has a podcast.

“There are standard campaign obstacles that you run into, like not fundraising as much as you want, or not getting a group’s endorsement. Or, you know, your candidate has parking tickets that they didn’t take care of,” Hayes says. “With this one, there’s a bit of, What’s this even supposed to look like?”

He and Bowman turned to a combination of mutual aid, regular home-schooling tips, and, of course, plenty of town halls and Q&As happening on Zoom. Some parts took longer to come together than others. “Tonia, could you put yourself on mute?” Bowman asked one participant in a Yonkers “town hall” after a dog barked over half a minute of his stump speech. The barking quieted, and attendees soon saw a small white terrier jump into one of the video panels lining the top of the Zoom screen. Another town hall was interrupted by Bowman’s 6-year-old daughter, who ran into his home office to show off a missing tooth.

“Our approach changed,” Bowman says. “The first thing we started asking voters was, ‘How are you handling this moment? What do you need? Is there anything we can do to help you?’” His campaign set up a phone-banking operation that has made more than 600,000 calls, in a district where 180,000 people voted in the 2018 election, and only 30,000 in that year’s primary. On the phone, campaign volunteers direct homebound seniors to mutual-aid groups that could deliver food, or undocumented residents to organizations that could help people who lost a job and were ineligible for a stimulus check. “That was always the initial touch point, before we got into the campaign and why you should vote for us,” he says. “That allowed us to remain human.”

Bowman also began to prepare for a series of debates with Engel. In prep sessions with his campaign team, the role of Eliot Engel was often played by Waleed Shahid, the communications director of Justice Democrats.

“We get into it a bit,” Shahid says. “I try to get under Jamaal’s skin as much as I can.”

“Waleed does Eliot Engel better than Eliot Engel,” Bowman says. “It’s pretty hilarious.”

In early June, Engel appeared in the Bronx and attended a news conference organized by the borough president, Ruben Diaz Jr., where he was caught asking Diaz at the podium for a chance to address the crowd. Engel did not realize that the microphones were already live and broadcasting to a local news livestream.

“I cannot have all the electeds talk because we will never get out of here,” Diaz said.

“If I didn’t have a primary, I wouldn’t care,” Engel said.

“Say that again?” Diaz asked.

“If I didn’t have a primary, I wouldn’t care,” Engel repeated.

“Don’t do that to me,” Diaz replied. “We’re not gonna do this. We’re not politicizing. Everybody’s got a primary, you know? I’m sorry.”

A reporter for NY1 posted a video of the exchange to Twitter, where it has been viewed more than 1.5 million times, and quickly made national headlines.

BronxNet, the borough public-access channel, aired one of the early debates that night at 8, just as the city curfew began. Bowman, Engel, and three other candidates dialed in via Zoom. Bowman appeared from his home office, sitting in front of a black bookshelf, wearing a suit jacket and a purple tie. He silenced his phone and turned on a ring light behind his laptop. The cord from his white earbuds draped down his chest.

The debate was moderated by Gary Axelbank, a journalist and talk-show host whom the Daily News calls “the closest thing the Bronx has to Charlie Rose.” His first question went to Bowman. “American cities are exploding in unrest like we have not seen in a very long time,” Axelbank said. He ran down a partial list of New Yorkers assaulted or killed by the police: Abner Louima, Patrick Dorismond, Amadou Diallo, Ramarley Graham. “If you are a congress member, what would you do to deal with this and address the myriad issues that have been raised by this very terrible situation?”

Bowman thanked Axelbank and said that the first time he was a victim of police brutality, he was 11 years old. “I was outside, just hanging out and having a good time with my friends. Someone called the police and said we were too loud, and the police didn’t just approach us and ask us to be quiet — they handcuffed me, they threw me against a wall, they dragged my face on the ground, and then they let us go. I had to go upstairs and show my mother my face, I was all bruised up.” Bowman has previously spoken about similar encounters with the police that extended into adulthood: being detained at a traffic stop then released without charge or an appearance in front of a judge. Another arrest, in front of his son, apparently, as he recalls, for stealing his own car.

“The thing that moves me the most is how my mother and I didn’t do anything. We had no thoughts about going to report it. We didn’t feel empowered in that moment,” he continued. “And that’s the reality of many Black and Latinos in this country. We live as if we are occupied by the police both physically and psychologically each and every day.”

He mentioned that Engel had supported the 1994 crime bill, which Bowman said should be repealed. “We need to focus on restorative justice in our communities, we need to hold police accountable — when they commit a crime, they should not be allowed to investigate themselves,” he said.

The protests that week had brought Bowman’s campaign, at least in part, back into the street. “We see the rage manifesting because people are living in poverty and they’ve been living in poverty for decades,” he said. “And until we deal with the institutional racism of poverty, seriously, this anger and rage will continue.”

For years, Engel has based his reelection campaigns on the privileges of his seniority in Congress, and the opportunities it allows to bring resources to the district. In the debate, he called this “bringing home the bacon.” Engel stared down into his computer from his apartment in the Bronx, seated in front of a red wall. One corner of a framed painting was visible behind him, and his chin sometimes dipped below the bottom edge of the screen. He began his response by asking for a moment of silence for George Floyd.

“I think that, unfortunately, part of the atmosphere that has been created in this country has been created because of Donald Trump,” Engel said, and argued that he had been one of Trump’s biggest congressional antagonists. “Mr. Bowman seems to like to talk about the crime bill,” Engel continued. “Yeah, the crime bill needs to be adjusted, needs to be changed. We’re working on it —”

Bowman interrupted. “But when you say you’re working on it —”

“Mr. Bowman, let’s let him finish,” Axelbank said. “Mr. Engel, why don’t you wrap that up.”

“That bill was a long time ago, and there are things that need changing,” Engel allowed. “This also was the bill that contained the Violence Against Women Act. Mr. Bowman probably doesn’t understand how it works in Washington. There are many, many different things in a bill, and you have to take the good with the bad.”

“Congressman Engel, institutional racism did not begin with Donald Trump,” Bowman said. “When you say you’re working on it, how long does it take? The 1994 crime bill was in 1994!”

“Look, Mr. Bowman,” Engel said. “You’re Black, and I’m not. I don’t pretend to be able to think that I have endured as much pain as you have, and your family has. But I have many, many Black brothers and sisters, and I feel their pain. And I feel my pain, because this is happening in the country I love.”

Engel continued: “I have a colleague named John Lewis, civil rights activist. By the way, he’s endorsed me for reelection. He has this saying, and I love it, and I always repeat it. He says, ‘We may have come here on different ships, but now we’re all in the same boat together.’”

“Yeah, but we came here in chains,” Bowman said. “It’s not the same thing! We have to address it differently, more urgently and aggressively —”

Axelbank closed his eyes and began to rock back and forth. He called on another candidate to weigh in.

Before the night was out, Bowman asked Engel if he apologized for his support of the crime bill. The congressman did not reply.

The next day began with another early morning. Bowman hosted more Zoom meetings, answered voter questions on a tele-town hall. Within a few days, the other primary challengers began launching attacks at him, not the incumbent. Bowman’s campaign began to tweet about “feeling the #Bowmentum.” Even Engel seemed to have noticed that something had shifted. When he introduced himself at the final debate, which aired a little more than a week later, he didn’t mention Trump, or his past work in Washington. It seemed he had decided to try to sound a little less like the Establishment, and a little more like Bowman. The country has changed in the past few weeks, he said. There had been a tremendous outpouring across the nation, by people of all ages.

“Black lives matter,” he said. “Black lives do matter.” The election was 13 days away.