This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On 106th Street in Rockaway Beach, a lime-green bunker faces the sea. From this concrete outpost, Peter B. Stein oversees the largest lifeguard corps in the United States. His 1,374 guards protect 13.3 million annual visitors to 14 miles of beach and 53 outdoor pools, from Coney Island to the Bronx.

In a city flush with generous contracts for civil servants, Stein, 75, has earned New York Post headlines for his outsize pay. He earns about $230,000 a year combined in lifeguard and union salaries. In the early aughts, when he drew a third paycheck as a gym teacher, Stein made more than the police commissioner.

An empire this lucrative must be stitched together — and then protected. In the 19th century, William “Boss” Tweed created a vast patronage network and enriched himself through kickbacks and bribes. Gus Bevona, leader of the building-maintenance workers union in the 1980s, earned a $450,000 salary and lived in an extravagant Soho penthouse. Like them, Stein relies on a playbook of patronage, power brokering, and intimidation. Since 1981, his supervisors have rigged swim tests, shielded sexual predators, and falsified drowning reports. One lifeguard refers to his crew as “La Cosa Nostra.” Through tabloid scandals, wrongful-death lawsuits, and 79 on-duty drownings since 1988 — at points, the city’s drowning fatality rate has been three times the national average — Stein has hung on like a barnacle from a bygone New York, successfully sidelining anyone who challenges him.

Then last summer, a flyer appeared at Connolly’s, a Rockaway bar popular with lifeguards. It had a photo of Stein. “Meet the godfather and mastermind,” it read. “Let’s make lifeguarding great again.” Only a few people knew who had created the sign, and it wasn’t obvious what was being proposed. But its existence alone sent a clear message: Someone had calculated that Stein was vulnerable enough to be challenged. His Tammany Hall by the Sea was in trouble.

In the summer of 1960, Peter Stein was a new 15-year-old lifeguard patrolling Manhattan Beach. The South Brooklyn neighborhood, full of middle-class families and brick buildings, was no Baywatch, and Stein — a squat Jewish kid with caterpillar eyebrows — was no David Hasselhoff. But it was on this sand that he would build his castle.

Stein endured a tough adolescence. His father died when he was 17, and he and his mother lived off Social Security. He was an unremarkable student, kept to himself, and quit the swim team after sophomore year. His lifeguard job was degrading. “The city treated us like garbage,” he later said. On hot summer days, his boss would send him to the parking lot to line trash cans. The indignity chafed.

While classmates became doctors and lawyers, Stein stuck with lifeguarding. He paid for college with his lifeguard salary, became a gym teacher at J.H.S. 223, a middle school in Borough Park, and continued to work the beach. Whatever kept him showing up each summer, it wasn’t a love of swimming. In his 20s, Stein worked at the lifeguard school on East 54th Street in the late winter and spring, teaching young recruits how to spot heatstroke, break free of a panicked drowning person, and revive unresponsive bathers using the Silvester method, a 19th-century precursor to CPR, which was still used at the time. During lunch, instructors ran, swam, and played basketball — everyone except Stein.

“I never saw him even put on a bathing suit,” says Ernie Horowitz, who attended Adelphi Academy high school with Stein and later worked with him at the lifeguard school. Stein arrived every day wearing a white button-down shirt. His training courses started last and ended first — Stein’s main occupation seemed to be arguing with his bosses.

In the mid-1960s, Victor Gotbaum, the table-thumping executive director of District Council 37, was growing this municipal-employee union. He lobbied lifeguards to join. Soon, two new locals were born: Local 508, for supervisors, and Local 461, for rank-and-file lifeguards. That the lifeguards had separate unions for management and labor would be key to Stein’s power. The president of Local 508 needed only to corral a few dozen supervisors in union elections to retain the post, rather than hundreds of unpredictable teenage lifeguards.

Colleagues from that era recall, with varying degrees of diplomacy, that Stein could be difficult. “He had a big mouth,” says Frank Pia, who worked alongside Stein for two decades. “He was very militant, a very tough guy,” says Alan Viani, a top DC 37 negotiator from 1968 to 1985. Horowitz is blunt: “He was a nudnik.”

Even as he alienated his peers, Stein cultivated a friendship with Gotbaum, who had earned the moniker “Mr. Labor” as he tripled DC 37’s membership rolls and negotiated with financiers and politicians to keep a nearly bankrupt New York City afloat in 1975. The exact circumstances of Stein’s ascent are hazy. Some who would know declined to speak on the record for fear that Stein might imperil their pension or a son’s job with the city. The rest are still on the payroll or dead.

By 1981, Stein, then 36, had become the citywide lifeguard coordinator — and the president of Local 508. By stocking the leadership of Local 461 with members of his inner circle, he would eventually control that union, too, in a brazen conflict of interest. Lifeguards who complained to their union representative about their boss found themselves speaking to the same man. Stein finally had real power.

New York City in the 1980s was a far more dangerous place than it is today, and beaches and pools were no exception. Lifeguards dove into the water to escape drive-by shootings. Teenagers hopped pool fences and hosted all-night parties with motorcycles, drugs, and water snakes. Lifeguards arrived at work to find floating corpses in pools and body parts washing up on beaches.

Lifeguards were out of control too. They ordered kegs at pools and tapped them while on duty. Coney Island guards threw cocaine-fueled parties and made T-shirts that read WE DRINK, YOU SINK.

There was, and there remains, a lifeguard hierarchy: first pools, then bay beaches, then open ocean. Rockaway Beach and its dangerous surf attracted the alpha lifeguards — and featured the wildest parties. The 117th Street shack had arguably the most notorious reputation. The staff there used 50-gallon trash cans to mix “bash,” a devastating concoction of vodka, rum, tequila, and Hawaiian Punch. At their Fourth of July party in 1984, hundreds of lifeguards drained 40 kegs, the equivalent of 6,600 cans of beer. On duty, they lured women off the beach and had sex with them in a nearby motel, in their cars, and even in the shack. Lifeguards regularly reported to work still hammered. “If you lit a match when people were signing in, it would go off,” recalls Edward Figueroa, a lieutenant lifeguard at the 117th Street shack for most of the 1980s. (He says he sent drunk subordinates home.)

But beach life was also alluring, even to more-buttoned-down teenagers. Janet Fash remembers visiting Rockaway Beach with her family in the late 1970s as a Park Slope teenager, when Park Slope was still a largely Irish-Catholic working-class neighborhood. She watched lifeguards tear off a female colleague’s bathing suit and throw it onto the jetty.

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,” her mother said. “You’ll never become a lifeguard.” But in 1979, Fash did. She loved the rescues and the camaraderie. In 1985, she made lieutenant and three years later became the city’s first female chief lifeguard. Fash met her future husband on the beach, and the couple moved to the Rockaways. She loved smelling the salty sea air as she drove home over the Marine Parkway Bridge. It helped that Stein knew how to take care of his own; they got pay raises, job protections, and pensions. In 1986, Fash got a dollop of Stein’s famed patronage when he hooked her up with a teaching position at 223.

Stein’s own teaching job was a point of contention in the press. In 1989, the New York Post questioned how Stein could keep beaches safe while also working as a gym teacher, hauling in a combined salary of $86,000 a year. But in a city grappling with a crack epidemic and annual murder rates up to eight times today’s, Stein gave the lifeguards a patina of competence, which charmed city officials. Stein attended to appearances, demanding that umbrellas with the Parks Department’s sycamore-leaf logo face the boardwalk. “We feel he’s doing a bang-up job,” a Parks Department spokesperson told the Post. “I can explain a drowning,” Stein once told Fash. “But I can’t explain why lifeguards aren’t in uniform.”

Off the beach, Stein was strategic in courting his political benefactors. He organized celebratory dinners at La Mer, a lavish catering hall on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, with VIP guests that included Mayor Ed Koch and Stein’s new boss at DC 37, Stanley Hill, who had replaced Gotbaum as executive director in 1987.

Stein had learned quickly how to leverage the union’s power. Just a year after becoming citywide lifeguard coordinator, he created a PAC called Politically Unified Lifeguard Labor, or PULL. According to a former lifeguard’s civil suit and a 1989 investigative report by the New York Post, Stein demanded $10 from every lifeguard in the city and threatened that any who refused would fail the swim test. Over the next several years, PULL made campaign contributions to Governor Mario Cuomo and Mayor Koch. “He was extremely, extremely savvy,” says Sal Albanese, a city councilman from 1983 to 1998 who also received pull donations. “Love him or hate him, he was a presence.”

Even Stein’s critics admit that his job is mind-bogglingly difficult: Recruit the nation’s largest seasonal lifeguard corps, despite a roughly 25 percent annual turnover, then protect millions of beachgoers, many of whom can’t swim.

New York City beaches all have their quirks. Dangerous whirlpools formed at Bay 22 in Coney Island because of an extended jetty. Orchard Beach has a steep drop-off that gets poor swimmers in trouble when the tide goes out. On rainy days, millions of gallons of feces-polluted water flush into the city’s coastline, sometimes forcing beach closures.

Taming Rockaway Beach has always been Stein’s greatest challenge. Seven miles long, it is the city’s only truly open-ocean beach, and it is brutal. At low tide, rip currents form — swirls of foam and sediment that suck swimmers out to sea. There are endless “cases,” lifeguard slang for swimmers in need of help. On a busy day in the 1980s, Fash and her crew would sometimes make 40 saves while also navigating gangs on the boardwalk, truant kids, and a local drunk approaching their chairs to proffer nips of tequila.

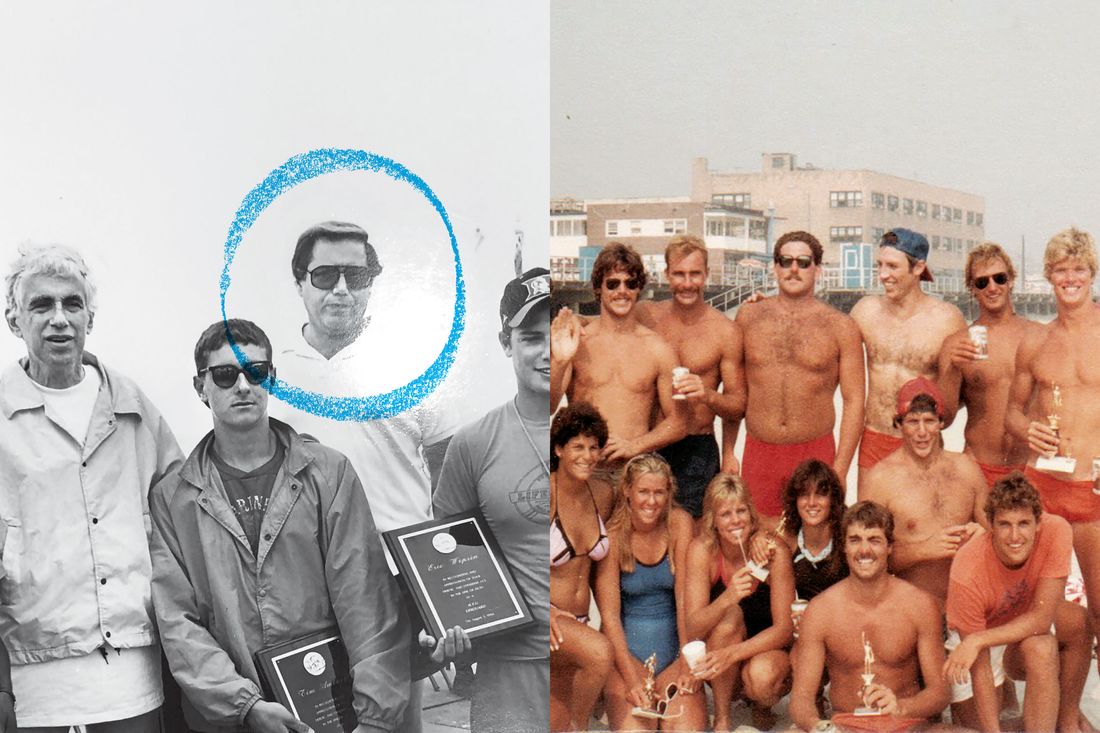

Back then, Joe McManus was Rockaway’s rising star. A court officer off the beach, he was six-foot-two, handsome, and Irish Catholic. He wrote articles for American Lifeguard and coached the varsity swim team at St. Francis College. His Rockaway squad regularly won the city’s annual lifeguard Olympics. In other words, McManus was everything Stein was not.

California was then setting the trends: improved beach surveillance, Jet Skis, tough training regimens. “We were in the playpen here,” McManus says. He wanted to make chief lifeguard, then perhaps borough coordinator, and modernize the city’s program. But when McManus began to organize lifeguards for national competitions without Stein’s approval, his ambitions made him a threat. In 1990, Stein transferred him to Beach 32nd Street in Far Rockaway, an underpopulated spit of sand far from beach babes and heroic rescues. Lifeguards called it “the 32-skiddoo.”

On June 20, 1990, McManus was working his lonely stretch of beach when his radio crackled. Two boys, Anthony St. Agathe, 15, and Bugani Wilson, 14, had just disappeared under the waves 12 blocks away. McManus grabbed his buoy and sprinted up the beach. He found the rescue effort in disarray and organized a sweep: Lifeguards lined up in two rows, perpendicular to the beach, and dove in unison, slowly tightening on the search area like a net. They failed to find the boys.

When he returned to his shack, McManus got word that Stein was “interviewing” the on-duty lifeguards, which McManus suspected was an effort to doctor the official narrative. One boy surfaced two days later. It took the other more than a week to wash up seven miles away in Long Beach.

The incident shook McManus. The next summer, he challenged Stein for the union presidency. When word got back to Stein, he exiled McManus even further afield — to a pool in eastern Queens — which made it harder to campaign. Still, Stein wasn’t taking any chances. Fash remembers Stein calling her at home to ask for her support. She had worked with McManus and thought highly of him. But Stein had gotten her the teaching job, and she worried that if she crossed him, and McManus lost, she’d lose her lifeguarding job. She was still nursing her son, so she decided to just stay home. Her vote, she admits now, “would’ve depended on the mood in the room.”

The vote took place at the end of the summer. McManus arrived at a union hall in Tribeca just as a fleet of 12-passenger Parks Department vans pulled up. Rockaway was his whole world, but Stein’s fiefdom extended across five boroughs. Lifeguards he had never seen before, from the Bronx and Coney Island, poured out. McManus had made a terrible miscalculation. Stein greeted him at the door.

“So you’re here,” Stein said. “Why don’t you go home and play with your gun?”

“I thought,” McManus recalls, “it meant, ‘Go home and shoot yourself.’ ”

The mood inside was equally dark. The ballots were anonymous, but lifeguards were instructed to write their names on the envelopes. McManus says he lost 100 to 8. Lifeguards came up to him afterward and said they would have voted for him had it been truly anonymous. “It was a one-shot,” McManus says. “And it failed.”

In December 1991, a Parks employee knocked on McManus’s front door and served him with disciplinary papers alleging a range of infractions, including leaving his assigned work location and using abusive language. He was terminated. McManus contested the charges, won a settlement, and moved to Florida to become a full-time lifeguard.

After the double drowning in Rockaway, trial attorney Jeffrey Lisabeth filed a wrongful-death case on behalf of the boys’ families. City investigators had learned that as St. Agathe and Wilson were floundering, their friend raced to lifeguard Jack Jordan’s chair and shouted for help.

“If they can’t fucking swim,” Jordan replied, according to court testimony, “why did they come to the beach?” Colleagues nicknamed Jordan the Angel of Death after several drownings on his watch.

Lisabeth thought his best shot was to stoke the anger of a Queens jury about white lifeguards callously letting Black kids drown. But at trial, Lisabeth’s case took a left turn. One of his first witnesses, lifeguard Regina Erhard Carey, then 26, broke down sobbing.

“It was the only time in hundreds of cases over 40 years that I had a Perry Mason witness that made a stunning revelation on the stand,” Lisabeth says.

Stein, Carey said, had ordered lifeguards to change key details in their reports after the drowning. Another lifeguard, Tom Dolan, testified that when he had warned Stein that Jordan had screwed up, his boss shot back, “Who do you think you are, Dick Tracy? You know what I want to hear.” (Stein did not respond to multiple interview requests.) After jurors left to deliberate, Lisabeth says, they sent him a note: He should ask for more money. The jury eventually awarded $2 million to the families.

McManus wasn’t done with Stein either. He tipped off Mark Green, who was then the city’s public advocate, that Stein’s dual control of the lifeguard program and the union fostered a culture of corruption. Green’s investigators spent three months going undercover at the lifeguard school. His office’s June 1994 report concluded that the lifeguard program was “swimming in mismanagement, negligence, secrecy, favoritism, conflicts, and even deception.” Lifeguards dressed up torpedo buoys with jackets and hats to sit their shifts; there was widespread favoritism in hiring, including passing people who literally couldn’t swim. A child had drowned in a wading pool while lifeguards allegedly played football nearby.

“Out of the couple of hundred investigations I did as public advocate, few of any agencies, few of any subjects, were as secretive or uncooperative as the lifeguard unit,” Green told the New York Times years later.

The report drew coverage in the daily papers and a City Council oversight hearing. But Jack T. Linn, who was then assistant commissioner for citywide services, and to whom Stein reported, believed Green had allowed McManus to skew the report’s findings. “You’ve got to be somewhat careful in accepting what you’re being told,” says Linn. “People’s motivations can be very complicated.”

Green remains adamant that Stein should have been prosecuted for falsifying drowning reports, but no criminal charges were ever filed. “He is still the head of the program?” Green asked, when contacted recently. “He’s the J. Edgar Hoover of lifeguards.”

Stein’s power base was (and still is) the union. Despite the scandals, Hill, the executive director of DC 37, pulled Stein deeper into union business. In 1995, less than a year after the public advocate’s report, Hill granted Stein “release time,” a coveted perk reserved for loyalists, which let Stein get paid for lifeguard work while doing union business.

The union also helped protect Stein against his Parks Department bosses. In the mid-1990s, the department attempted to rein him in, creating a citywide director for beaches and pools to oversee the lifeguard program. Brian J. Thomson, the new director, promised to spruce up lifeguard shacks and advertised promotional opportunities and a Jet Ski–training course.

Stein resented Thomson and the potential scrutiny he represented. DC 37 filed a grievance with the Office of Labor Relations demanding that Thomson be removed. In 1996, the city agreed to eliminate his position and shifted responsibility for the lifeguard program to the first deputy commissioner, whose busy portfolio meant less scrutiny of Stein’s operations. Julius Spiegel, who served as Brooklyn’s commissioner of parks from 1981 to 2010, says the Parks Department didn’t have the political clout to go up against the union. And even if it had, it couldn’t count on City Hall’s support. In September of that year, Stein circulated a handwritten note bluntly reminding lifeguards that his efforts paid their wages. “The check you are now receiving,” he wrote, “is the result of that hard work, tough negotiations and aggressive enforcement.”

Meanwhile, at DC 37 headquarters, Hill, a college basketball star turned welfare caseworker and finally labor leader, had allowed the union to become a feeding trough. From 1994 to 1998, according to a KPMG audit, union officials spent $1.5 million on Town Cars; more than $2 million on catering; $2.9 million for trips to Hawaii, Israel, and Bermuda; and $29,250 for jumbo shrimp at a Chicago convention. Kickbacks abounded, auditors later found, including a scam involving overpriced turkeys for the annual Thanksgiving giveaway.

But by the fall of 1995, there was a problem. Mayor Rudy Giuliani wanted DC 37 to approve a contract containing a two-year wage freeze. The proposal was unpopular with the union’s mostly working-class members — cafeteria employees, zookeepers, librarians — who earned a median of $27,500 a year. Yet union leaders worried that if they voted it down, Giuliani might go after them for corruption. “He and his team were former prosecutors and knew where the bodies were buried,” says Richard Steier, editor of the labor newspaper The Chief-Leader. “The feeling was, They will sic the hounds of hell on us.”

Hill needed “yes” votes. At the union’s Barclay Street headquarters, officials steamed open envelopes and swapped out “no” ballots, according to whistle-blowers and a subsequent criminal prosecution. Local presidents were dragooned into the effort.

Stein’s lifeguards accounted for less than one percent of the DC 37 empire, which represented 120,000 members across 56 locals. But he answered the call — and then some. In both lifeguard locals, the contract passed by a combined tally of 440 to 3. The auditing firm Kroll, which later investigated the rigged election, mentioned Stein in its final report, calling the lopsided vote total “unusual.”

The contract passed, but DC 37 bosses went down anyway. The Manhattan district attorney convicted dozens of union officials for embezzlement, vote fixing, and other charges. Stein backed Hill to the end. When Hill finally resigned, in 1998, AFSCME, a powerful national union (it currently has 1.4 million members), tapped Lee Saunders, a national official with a reputation for probity, to clean house at DC 37.

While Saunders projected “the image of a tough sheriff trying to take back Tombstone,” according to a 1999 story in The Village Voice, he also had ambitions that might be thwarted if he upset union loyalists. “He had no interest in fundamentally reforming the structures or the cultures of the union,” says Joshua Freeman, a professor of labor history at Queens College. Saunders tapped Stein to become a vice-president, passing over reformers who had fought corruption. The post came with an $18,000 annual stipend. “People that were part of the group got taken care of,” Steier says. (A spokesperson for Saunders declined to comment; he has since become president of AFSCME.)

Stein had not just avoided punishment for overseeing falsified drowning reports and fixing the union’s contract vote; he’d received a promotion.

On the beach, Stein rewarded loyalty the same way. His right-hand man was Richie Sher, a former Marine, slim and quiet with a mop of curly white hair. Sher had started lifeguarding in May 1958, and for decades he coached the swim team at Bushwick High School, from which he recruited heavily. Lifeguards clamoring for overdue promotions to this day bemoan the “Bushwick crew,” a clique of Sher’s former students with prominent posts, including Franklyn “Bubba” Paige, president of Local 461 representing rank-and-file lifeguards, and Vladimir Peña, a rough and reliable chief lifeguard who served two years in prison for manslaughter.

The Bushwick crew helped Stein enforce a strict code of silence. In 1996, the city’s Department of Investigation opened its own inquiry: Operation Splash. But Stein’s men were ready. Joe Manderson, a borough coordinator, physically threatened investigators when they attempted to seize lifeguard-school records. Undercover investigators then trailed Sher. They found him falsifying time cards, claiming he was on the clock while dining, commuting, and “meeting with women.”

The city finally forced Stein to choose between his jobs running the lifeguard union and running the lifeguards in the mid-1990s. Stein took the union post, retaining a highly paid lifeguard job, while Sher took over as lifeguard coordinator. But among lifeguards, it was clear Stein was still in charge. “Richie Sher had no say in nothin’ in this,” says Richie Arroyo, who was among Stein’s longtime supervisors before retiring as Bronx borough coordinator in 2019. “At that point, it became obvious that Peter would do whatever it took to stay in power.”

The inspector general recommended in 2000 that Sher be disciplined for his time theft, but he remained in his job. Sher had long boasted that being a lifeguard gave him another perk. “It has a glorified reputation,” Sher bragged to the Times in 1982, when he was a mere supervisor. “It has a reputation for, well, you know, girls.” But Sher had his own unsavory reputation when it came to young female subordinates.

In the mid-1990s, one female lifeguard was at the West 59th Street pool when Sher approached. He was paging through a Victoria’s Secret catalogue and pointed at a nightgown. “I would like to see you in that,” he said. “Would you wear that for me?” She was in her early 20s. She turned beet red and tried to smile. Sher was feeling her out, she later realized.

In January 1997, around the time he took over as coordinator, Sher was arrested. Although the police records are sealed, investigators who authored the Splash memo called the arrest “particularly troubling” in light of allegations of rampant sexual misconduct by lifeguard supervisors. The charges were later dropped.

It wasn’t just Sher. His supervisors across the city looked the other way as lifeguards were harassed and assaulted by their colleagues. City investigators were frustrated when they looked into allegations of sexual wrongdoing: Many victims were afraid to file grievances with the union because supervisors also held high-level posts in the local. A complaint, the Splash memo concluded, might very well be read by a woman’s assailant in his capacity as a union official. “They make sure it’ll be he said, she said,” says another female veteran lifeguard, who says she was harassed by Sher. “They’ll cover for each other.”

In 1998, Jenny Pereira was a 17-year-old lifeguard showering at the West 59th Street pool. When she put shampoo in her hair and closed her eyes, Ruben Brand, a chief lifeguard in his early 30s, grabbed her from behind. She screamed and fled. Pereira filed an EEO complaint. Brand was demoted, but he continued working. “They didn’t fire people when they considered them a friend,” Pereira says now. “And if you were a girl who slept with them, you got ahead.”

Just as he protected those closest to him, Stein had ways of keeping those who crossed him in line. Every spring, applicants — from high-school swimmers to middle-aged teachers and firefighters — descended on the West 59th Street pool for the swim test. Stein watched from an office window high above as shivering lifeguards waited to dive into the water. His lieutenants on the pool deck gawked at exposed flesh, made lurid comments, and cursed profusely.

Every year, Fash steeled herself for the humiliation. “It was an uncomfortable feeling,” she says. “You just wanna take the test and get out.”

The time to beat for a beach post was 440 yards in six minutes and 40 seconds, a minute slower for pools. Supervisors timed swimmers on stopwatches. Lifeguards who had previously challenged Stein were told they’d missed the cutoff, they say. Failing meant making another trip into the city or perhaps picking up the phone to ask Stein for a favor. Or sometimes no job at all.

His men operated side hustles too: The supervisor who ran the lifeguard school moonlighted as a bartender at Connolly’s. Lifeguards could pop in for a drink, hand over a wad of cash, and avoid the indignity of the test. By the aughts, Stein’s inner circle included men in their 50s and 60s who were still technically required to pass.

One year, Arroyo, the retired Bronx borough coordinator, had a sore shoulder. “There was no fucking way I could pass that test,” he says. He jumped in the water, swam a few laps, and was told he’d passed. The attitude was “You’re here because of us,” Arroyo says. “Now you owed them.”

Unlike in city agencies like police and sanitation, which offer formal exams for promotions, Stein and Sher decided who made lieutenant, chief lifeguard, and borough coordinator. Sometimes they promoted based on seniority, but plum jobs were usually rewards for loyalty.

Those favors came in handy. Every few years, Stein rounded up 15 to 30 supervisors and stood before them, arms folded, as they unanimously reelected him president of Local 508. Once, Arroyo brought another supervisor who wasn’t familiar with the process. When the meeting began, he stood up.

“I nominate Richie Arroyo,” he said.

Stein’s eyes narrowed. The entire room turned to look. Arroyo jumped out of his seat. “I decline!” he cried. “I decline!”

By the early aughts, after a decade of scrutiny, Stein was increasingly paranoid. At the 106th Street office, he frequently retreated into a private back room to rage at supervisors. He called at 3 a.m. to obsess over discrepancies in incident reports. Arroyo once had dinner with other veteran lifeguards. The next day, Sher called and asked what they’d discussed.

Stein’s paranoia was well founded. The lifeguard profession can attract prideful, testosterone-charged men. Stein culled some troublemakers with the swim test, but others remained.

Miguel Castro cut an intimidating figure. He was fit, with a shaved head. He competed in triathlons, and even today, at 62, Castro is one of the few supervisors who can legitimately pass the swim test. He was also one of the few “yes” votes for Joe McManus in the 1991 union election. He had a fearsome reputation; rumors swirled that he worked as a collector for a Colombian drug gang.

“I was borderline sociopathic,” Castro says of his mind-set at that time. “I used to get a thrill out of pissing people off.” In 1997, Castro began to feud with Arthur Miller, a Brooklyn borough coordinator, about equipment shortages and his propensity to ignore Miller’s radio calls. Castro finally challenged his boss to a fight after work, and Miller filed a complaint with the Parks Department. What followed was either retribution, as Castro alleges, or simply Castro courting confrontation, as his bosses later testified. Either way, he began to spar with Stein loyalists in Coney Island. They got into a fistfight on the beach, and one member of Stein’s crew made phone calls to the school where Castro worked, accusing him of being a pedophile.

In 2005, Castro filed a civil suit against Stein, Sher, and the Parks Department, alleging years of retaliation for his vote for McManus. At a deposition, Stein and Sher blamed Castro’s fights with fellow lifeguards on his disagreeable nature. “You got to understand,” Sher said. “I have a lot of enemies because I’m a boss. He has a lot of enemies.” A judge dismissed Castro’s suit, and the feuding died down. “They leave him alone,” said Omer Ozcan, a 34-year-old lifeguard who works the same section in Coney Island. “When he verbally attacks them, they just say, ‘Okay, Miguel.’ Maybe they just don’t want to deal.”

The beach drama played out in the early years of the Bloomberg administration, which had ushered into the city a new era of technocratic corporatism. To lead the Parks Department, Michael Bloomberg tapped Adrian Benepe, a department lifer with a tony résumé (Upper West Side, Horace Mann ’74, Middlebury ’78).

Over the next decade, Bloomberg and Benepe created the High Line, overhauled Brooklyn Bridge Park, and allowed a small hamburger kiosk called Shake Shack to open in Madison Square Park. The modernization extended to summer fun: The city renovated the million-gallon McCarren Park Pool, started the Swim for Life program for second-graders, and built the $66 million Flushing Meadows–Corona Park Pool with an eye toward an Olympics bid.

Stein fought to protect his turf from their innovations. He tried to “featherbed” Swim for Life, demanding that union lifeguards work alongside the program’s coaches. When Benepe hired a private contractor to manage the Flushing facility, Stein and DC 37 campaigned for his lifeguards to take over, finally succeeding in 2014.

Stein’s machinations may have been at odds with the new City Hall, yet he still managed to operate with near impunity. The Parks Department simply had too much work to do with too little money and minimal political clout. It managed 5.2 million trees, including nearly 600,000 on city sidewalks (at times, the backlog for stump removal stretched 15 years), while sparring with hot-dog vendors, illegal sidewalk artists, and dog owners angry about off-leash hours.

Beaches and pools made Benepe anxious. “Every summer was a countdown from when we opened to draining the pools to say nobody drowned,” he says now, a feat he achieved only once in 11 years. Stein held Benepe hostage, as he had done with his predecessors. Looming in the background of every negotiation was the implicit threat that lifeguards might not show up to work on the Fourth of July weekend. “If it’s 100 degrees, there’s two scenarios,” Benepe says. “We send every cop in the city to keep people out of the water and there’s a riot, or 15 people drown.”

Stein got the job done well enough for Benepe to leave him alone. “He’s never had anything stick,” says Benepe. “For all his faults or perceived faults, Stein and his team kept millions of people safe.” The tabloids took a dimmer view. In 2003, his former colleagues at the Board of Education were still smarting that Stein had negotiated a $53,000 severance package to leave what had become a no-show job as a gym teacher. They leaked details of the settlement to the Post. The paper hit Stein with the headlines “Problem Teachers Going on $abbatical,” and “City Can’t Fire Do-Nothing- Guy.” Stein responded by suing the Board of Education, alleging that he’d been coerced into signing the package.

Lifeguards of every rank began to swagger. “Everyone in the Parks Department hates the lifeguards because we get away with murder,” says one veteran pool supervisor. “It gets worse and worse every year.”

After Ruben Brand harassed Jenny Pereira, his bosses instituted a rule that Pereira could not use the lifeguard locker room when Brand was on duty, she says, apparently to remove any opportunities for abuse from him. But that precaution wouldn’t be enough. In December 2007, Brand was arrested for molesting two underage girls at the 59th Street Pool.

Afterward, Javier Rodriguez, an assistant lifeguard coordinator, called Pereira. She had since become a police officer, and Rodriguez asked if she would recant her 1998 complaint to help protect her former assailant, Pereira says. Pereira refused. Brand was convicted and is now a registered sex offender.

More troubling still was an incident in 2006. Boris Braverman was a 17-year-old rookie lifeguard in Coney Island. Veterans hazed the newbies, or “horns.” Senior lifeguards would make them sit their shifts in the chair. And then there was the “shake and bake,” when they were doused with a hideous gumbo of ketchup, flour, eggs, sunscreen, and sand.

Still, working the beach was Braverman’s dream job. In his first month, he got his photo in the Daily News after rescuing a drowning girl. That summer, the Coney Island crew organized a shack party. Braverman volunteered to flip burgers; dozens of lifeguards and their friends showed up.

As the revelers got increasingly intoxicated, a group of older lifeguards pulled down men’s pants, then started stripping them entirely. When Braverman fell into their sights, they grabbed him, pulled off his clothes, and tied him to the boardwalk railing. Braverman thought it was part of a game. Then he heard someone call for a broomstick.

Several older lifeguards took turns sodomizing Braverman. Another snapped photos that he later posted to Myspace. His final assailant, a female lifeguard, pressed the wooden handle into his rectum. After he was untied, she punched him in the face. A friend finally stepped in, and Braverman fled the party. Another lifeguard who was present also remembers witnessing the attack.

Within a few days of the assault, a female lifeguard climbed up into Braverman’s chair with him. She asked how he was doing. When Braverman began to cry, she intimated that he should keep the incident to himself. Later, one of his attackers was more direct: “Don’t you fuckin’ say shit, or we’ll fuck you up.” Braverman did as he was told. His nickname on the beach became “Broomstick.”

“I was filled with so much shame and horror, I just wanted to get past it,” he said. “I wanted to be on the beach, get a tan, talk to girls.” Braverman is now preparing a civil suit against the city under the New York Child Victims Act, signed into law last year, which extends the statute of limitations for sex crimes.

In interviews with more than two dozen lifeguards, none ever suggested Stein had been sexually inappropriate. “His thing is about power, being in control,” one said. “Fucking with people’s lives. I think he gets off on that.”

In retrospect, Stein and Janet Fash had always been on a collision course. Over the decades, she grew angry as bodies washed up. Her own lieutenant was unqualified, she says, but loyal to Stein. September 2, 2004, was Fash’s day off. That afternoon, a rip current sucked 17-year-old Mahin Iqbal out to sea; his body surfaced two days later. An investigator determined that Fash’s lieutenant had deployed too few lifeguards when Iqbal drowned. Fash raged at Sher and demanded he give her inept subordinate a job at an indoor pool and “get her the fuck out of here.” Sher complied, in part: He rewarded the subordinate with a year-round job, though he still permitted her to work the beach during the summer.

Fash’s breaking point came in 2006. Rockaway parents had started a program to train teens for lifeguard jobs, and on swim-test day, 19 of 20 failed, despite their coach having regularly timed them passing. Fash was outraged. The program, she suspected, constituted a threat to Stein’s need for total control.

So she started making noise. She met with Community Board 14, which covers Rockaway Beach. Residents were angry — about beach closures, too few lifeguards, and now their kids’ being failed on the test. They set up an ad hoc committee and pestered the City Council. In 2007, Oliver Koppell, a city councilman from the Bronx, began to scrutinize the lifeguard program after hearing Fash’s concerns. “The whole thing was controlled by Stein, and Parks commissioners ceded control to him,” says Koppell, who had himself worked as a lifeguard at Orchard Beach for a summer in the late 1950s. “We broke into his universe.” But after concluding oversight hearings and a tour of the West 59th Street pool, he was content that the lifeguard program had made adequate reforms. He moved on.

Stein retaliated by sending Fash half as many lifeguards. He wanted to make her anxious that someone would drown, she alleges. She pressed on, testifying at a City Council oversight hearing. But Liam Kavanagh, who oversees the lifeguard program for the Parks Department, wasn’t interested in Fash’s allegations of favoritism and chronic safety lapses. He declined to hire an independent monitor, he told the Times, “for a couple of unsubstantiated rumors.”

Kavanagh has consistently defended Stein and Sher to the City Council and the press. “All of the indicators are positive,” he says. “There are some terrific people who run different aspects of the program year in and year out.” Former Parks officials heap praise on Kavanagh, calling him a squeaky-clean product of Catholic schools whose 39 years of experience make him indispensable. But others argue that his longevity has become a liability; so many misdeeds have occurred on his watch that his legacy is now tied to Stein’s. Kavanagh did acknowledge that Stein’s dual roles in the union and Parks Department have been discussed. “It has come up. We have looked into it. No one brings up, despite concrete examples, how that comes in or how that affects the operation. I don’t know of any specifics,” he says.

The Parks Department declined to make Stein or Sher available for comment. “Parks, like society, has evolved and we take all allegations of misconduct, particularly any reports of sexual harassment, very seriously,” said a Parks Department spokesperson, Meghan Lalor, in a written statement. “We require our lifeguards to take sexual harassment training annually and investigate everything that is brought to our attention and discipline accordingly.” When pressed on the myriad allegations in this story, she objected only to Fash’s claim that Stein provided her with too few lifeguards.

For two decades, Stein has been careful to curate Kavanagh’s understanding of the lifeguard program. One veteran pool supervisor says that, several times a year, Marty Kravitz, the Manhattan borough coordinator, calls to warn him that Kavanagh is making rounds in the area. “Call me as soon as he leaves,” Kravitz would say and later demand a detailed report on what they discussed. Stein need not worry, the supervisor adds. Every year, he complains about the same broken shower, every year Kavanagh jots down notes, and every year it goes unfixed. “Nothing ever changes,” he says.

In 2013, after Hurricane Sandy, Stein moved Fash to Beach 32nd Street, the same distant post to which Joe McManus had been isolated. The shack was her Elba, she joked.

Stein’s patronage machine kept his lieutenants well fed. Between 2008 and 2019, Kravitz, the Manhattan borough coordinator, saw his salary jump 60 percent to $168,362 a year. Allyson Jerrahian, a secretary at the lifeguard school, saw an increase of 61 percent to $141,261. For those without high-school diplomas, a year-round pool job was a ticket to the middle class. “You give someone with no degree a $65,000 job,” says Edwin Agramonte, a 47-year-old veteran lifeguard. “That’s real power.”

Stein’s own lifeguard compensation hit $175,463 in 2019, plus tens of thousands more in union pay from DC 37. He lived well: He drove a late-model Mercedes-Benz, had a vintage Jaguar XJS, and vacationed in Mexico. (By comparison, the lifeguard chief in San Diego, a highly demanding, year-round post, earned $152,924 in 2019.)

The parties and the impunity continued. In 2009, Post reporters caught on-duty lifeguards wearing headphones and “canoodling” with women and crates of Bud Lime stacked outside the Orchard Beach shack. “All that’s missing are the Greek letters,” the Post wrote. A few days later, lifeguard Luis Peralta, 25, was arrested for nearly drowning a teenager who had disobeyed his warning to stay out of a pool during cleaning. Peralta was rehired the next summer.

On the evening of July 4, 2013, Francisco Lorenzo, a 39-year-old chief lifeguard, organized a party in the Bronx. He charged admission and admitted minors. Security footage captured dancing, drinking, and drugs. The Parks Department demoted two supervisors and transferred four others. Lorenzo, meanwhile, lied to Parks investigators and showed no remorse for throwing the party, according to legal documents. An arbitrator let Lorenzo keep his job, and the lifeguard union later fended off a city lawsuit that again sought to terminate him. In 2017, after police arrested Lorenzo for molesting a male subordinate at a pool on East 23rd Street, he finally hung up his whistle.

Between 2011 and 2013, 11 people drowned at pools and beaches with lifeguards on duty. In July 2011, Jonathan Proce and Bohdan Vitenko, both 21, were practicing breath-holding techniques at Lyons Pool on Staten Island in preparation for military basic training. They blacked out underwater. Three fewer lifeguards were working than required by the city’s Health Code, and a supervisor wasn’t on duty. When lifeguards finally pulled them out, they couldn’t find the pool’s defibrillator. Vitenko died that morning, and Proce died in the hospital four days later. Their families sued and were eventually awarded $2.1 million.

Lifeguards who complained about lax safety standards were targeted. On Labor Day 2015, Barbara Torres, a supervisor at Thomas Jefferson Pool in East Harlem, ordered lifeguards not to drink on duty. After lunch, red Solo cups began appearing. Torres called her boss, and he sent home lifeguard Felix Velez. Her crew was furious. As Torres left the pool, Felix’s sister, Natasha Velez, came sprinting up the block and hit her across the temple with a cell phone. Lifeguards recorded the attack on their phones. Torres tore a foot ligament fighting her off. The state later charged Natasha with assault, but the next year, it was Torres who was punished for making waves: She failed the swim test twice, was stripped of her title, and was moved to an indoor pool. Felix Velez continues to work as a lifeguard.

In 2016, a member of Stein’s inner circle, Freddie Bomhoff, died. He had taken bribes to pass lifeguards on the swim test, but, unlike the rest of top management, he was beloved as a Dionysian charmer of the beach. At a memorial on the Rockaway boardwalk, dozens of aging lifeguards showed up, some whose tenures dated to the 1950s. Stein and Sher were among them. So was Fash. After a few speeches, Fash’s husband paddled beyond the waves on a surfboard with a wreath of orange and green flowers, the colors of city lifeguard uniforms. As the crowd broke up, Fash approached Stein. She wanted to talk about getting more lifeguards for her section.

“Now is not the time,” Stein said, holding up his hand.

“When is the fucking time?” she asked.

The next day, Stein came to Fash’s shack. For nearly two hours, he spoke about the early days of the union, his strategic decisions over the years, and how many of his closest lieutenants were stupid. Fash just sat and listened. She realized Stein was a lonely man. His lieutenants remained, but they were aging. Sher, the oldest of the bunch, was closing in on 80. Bomhoff was gone, and now the tide was coming in for Stein.

Another group of veterans remained as well — men in their 50s and 60s whom Stein deemed insufficiently loyal to be rewarded with his most plum jobs. Such a group of malcontents is always dangerous, whether in a banana republic’s army or a city’s lifeguard corps.

Ulises Peña, a longtime lieutenant lifeguard at Orchard Beach, had been a reliable foot soldier for more than three decades; he had reelected Stein in sham votes and handed out flyers for union-backed candidates on Election Day. But in 2018, Peña complained about not getting a promotion, and the next summer Stein moved him from his beloved Bronx beach to an indoor pool. It was Peña who put together the anonymous flyer that showed up at Connolly’s last summer. The cut-and-paste job, all strange angles and different fonts, read like a kidnapper’s ransom note. WHAT DOES YOUR UNION DO FOR YOU AFTER THEY TAKE YOUR DUES??????, it screamed, along with other grievances about unfair promotions and retaliation.

Miguel Castro, now 62, still worked at Coney Island, but he had mellowed, thanks in part to a new wife. He had met Peña at the lifeguard school in 1985, and they maintained a loose friendship. With Castro’s encouragement, Peña drove down to Coney Island and gave a handful of flyers to Castro’s friend Omer Ozcan, who had grown frustrated after Stein promoted younger lifeguards with better connections — a friendship with a supervisor or a dad in the NYPD — over him. Ozcan pinned them to shack bulletin boards in Coney Island.

Lifeguards took photos and texted them around. It popped up on NYC Lifeguards, a Facebook group with more than 1,100 members. Castro also connected Peña with Fash. Domingo Pineda, 53, was tired of bending the knee for his preferred pool assignments. He joined too. They created a WhatsApp group, named it “Justice League” after the DC Comics superhero team, and began to plot. Members of the group filed FOIL requests for their bosses’ salary histories and the lifeguard seniority list. Peña and Ozcan covertly recorded meetings and phone calls with David Catala, director of DC 37’s Blue Collar Division, and Bubba Paige, president of Local 461.

During their amateur investigation, they uncovered that, in 2019, Paige had been improperly paid $102,000 as a supervisor while representing the rank-and-file lifeguard union. He had also failed to hold a union meeting in years. Fash argued that they take aim at Paige, score a quick bull’s-eye, and then focus on Stein. She didn’t want to shoot too high and miss. On January 10, the rebellious lifeguards met at a barbecue joint in Rockaway. Fash brought the papers, and they all toasted as Ozcan and Rafael Sequeira, who worked with Peña at Orchard Beach, signed formal union charges.

When he reviewed the charges, Rich Abelson, chairman of AFSCME’s judicial panel in Washington, D.C., agreed they were worth investigating. He set a trial for March 31. A conviction might force an election — even terminations. If they won, the Justice League would gun for Stein next.

Then, a few weeks before the trial, COVID-19 swept across New York. Abelson delayed the hearing. On April 16, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced he would close outdoor pools for the summer and postpone lifeguard training. He set no date for beaches to open. Adrian Benepe, the former Parks commissioner, took to Twitter and the Times op-ed page, imploring de Blasio to put lifeguards on beaches and prevent inevitable carnage. Sure enough, on May 22, the Friday before Memorial Day, a 24-year-old drowned near Beach 91st Street in Rockaway.

Even in pre-COVID times, lifeguards would not have been on duty until that Saturday, but the death highlighted the looming crisis. A few days later, lifeguards resumed training. In a June 11 radio appearance, de Blasio promised that lifeguards would be ready to be deployed as soon as beaches were safe to open for swimming. Once again, the city needed Stein to work his magic: prepare an army of lifeguards in the midst of a pandemic and, later, political protests and curfews. The virus had thrown him an unexpected lifeline — or at least, given him new leverage. A crisis was no time for regime change.

At the Chelsea Recreation Center, supervisors met applicants wearing face masks and gloves. When Fash went for her test, Javier Rodriguez, one of Stein’s deputies, put her in a heat with faster, younger swimmers; kids 40 years her junior lapped her. Still, she slipped in under the cutoff. When Castro arrived to test, Rodriguez, a man he had known for 42 years, refused to speak to him. Both he and Fash worry about retaliation when the beaches reopen — unfavorable beach assignments or perhaps no job at all.

Meanwhile, the AFSCME trial of Bubba Paige remains postponed. Fash is despondent. Stein knows his way around the national union, and she fears he is outmaneuvering them. With beaches closed, she spends her days gardening and jogging. Full-time lifeguards are still getting paid, but part-timers aren’t. Domingo Pineda, whose reduced hours were the reason he’d joined the Justice League, worries he won’t be able to support his two teenage children.

The prospect of no summer wages is an opportunity for Stein to remind them, once again, that he is their patron. In a four-page letter co-signed with Paige in early May, he boasts about securing paid time off for cancer screenings and promises some pay for seasonal lifeguards if beaches don’t open. It closes with a plea in large font: “PLEASE REMEMBER THERE IS STRENGTH IN UNITY.”

*This article appears in the June 22, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!