Thanks to the president’s not-so-veiled threats to refuse to accept the legitimacy of mail ballots that are likely to go overwhelmingly for his opponent in a slow count following Election Day, and some Democratic talk of refusing to acknowledge a second Trump win without a popular vote plurality, there’s been a lot of justified attention focused on what happens on Election Night and immediately thereafter.

I’ve been one of those to warn that Trump might even declare victory on Election Night if he’s ahead in key states at that point. In such a declaration, he’d likely announce his win on the strength of the in-person voting Republicans are expected to dominate and claim that subsequent mail ballots are too rife with fraud to be counted. The scenario by which Trump would then nail down a purloined victory in the Electoral College (short of an actual coup to impose it) has never been all that clear, and its improbability might prevent even this lawless president to go there.

To assess his options, it is necessary to go down one of the deepest rabbit holes in U.S. election law: What happens during the 37 days between December 14, when electoral college votes are cast and collected, and January 20, when the next presidential inaugural is held. There’s an even smaller and more fateful two-week window before the inauguration during which a newly elected Congress counts and certifies the Electoral Vote on January 6, and hastily makes other provisions for the presidency if neither candidate has a recognized majority.

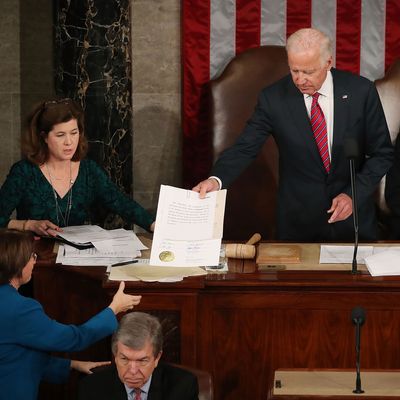

This timetable was created by the combination of vague constitutional language on how to formally elect a president, and a confusing and possibly unconstitutional statute from 1887 (ten years after an election dispute that nearly triggered a second Civil War) called the Electoral Count Act. In a normal, uncontested presidential election year, this process draws little or no attention because the outcome is ordained and is generally known (in all presidential elections since 1876 other than the 2000 cliffhanger) on or shortly after Election Day. Typically governors certify the winning electoral college slate before the ECA’s “safe harbor” deadline six days before the electoral college ballot box is locked (which purportedly means no one can challenge them later). The votes are then cast, the vice-president, in his or her role as president of the Senate, reads them out to a Joint Session of Congress on January 6. Lawmakers then immediately certify the count, and during all this time the new administration is getting ready to assume office.

This year, however, in part because of the expected slow count (and possibly recount) of ballots, and in part because of lawsuits and possibly presidential efforts to interfere with the counting of all those “fraudulent” mail ballots, it’s not at all certain that highly contested states will meet this year’s “safe harbor” deadline of December 8 for identifying a clear winner, or that when the Electoral College virtually “meets” on December 14, there will be just one slate per state sent in for tabulation. So depending on how much of a factual and legal quagmire a putative Republican rejection of the legitimacy of mail ballots creates, we could have pols and judges and pundits from both parties claiming victory, and big crowds in a thousand streets backing them up, by the time the new Congress takes office on January 3 and prepares to count Electoral Votes three days later.

According to the constitutional scheme, the President of the Senate, who would be current Vice-President Mike Pence, would “announce” the votes to a joint session of the newly elected Congress. The Electoral Count Act clearly expects the states and ultimately Congress (barring a contrary vote by both Houses of Congress, gubernatorial certifications are supposed to be recognized), not the veep, to decide which slate to announce, but if Pence were to only announce Trump-Pence slates citing his constitutional prerogatives, it’s unclear what would happen. Again, the constitutionality of the ECA has never been tested. And the effect of its provisions governing disputed slates would totally depend on which party controlled Congress, and which party controlled the governorship of the affected states.

We actually have a small and harmless example of the temptation Pence could face. In 1960, Hawaii’s Republican Governor certified a very narrow Richard Nixon victory in that state. A later recount put John F. Kennedy in the lead, and Hawaii certified a second, Kennedy slate. Since Hawaii’s three electoral votes didn’t really matter in an election Kennedy had already won, Nixon, as President of the Senate, graciously recognized the Kennedy slate and “recommended” that Congress go along. In an identical situation, if the election was unresolved and it was Florida’s 29 electoral votes at stake, do you think Mike Pence would help Biden and Harris get across the line? I don’t think so.

No wonder when Congress confronted a contested presidential election in 1877, its leaders (along with lame duck president U.S. Grant) created an extra-constitutional Election Commission to resolve the mess. But they had the luxury of a March 4 inauguration. Since 1933, presidents are inaugurated on January 20. So there won’t be time for deliberations or the kind of Grand Bargain crafting that eventually brought an uneasy peace in 1877.

If for whatever reason Congress cannot certify an Electoral College winner (there’s even a not-entirely-implausible scenario where Trump and Biden might tie with 269 electoral votes each), then the newly-elected House would be charged with choosing a new president, under a bizarre constitutional provision giving each state delegation one vote — or no vote at all in the case of ties — and requiring 26 delegations for election. Currently Republicans control a bare majority of 26 House delegations, and a calculation by Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball suggests they are likely to maintain that number even if they lose some House seats in November. If the House cannot reach a decision, the newly elected Senate would have the opportunity to elect a vice-president who would fill the presidential vacancy on January 20, and if that, too, failed, the Presidential Succession Act would kick in and you could be looking at President Nancy Pelosi on Inaugural Day.

If this sounds like two weeks of sweaty madness with the highest possible stakes involved and the whole world watching in horror, that’s almost certainly correct. But that’s the system we have inherited thanks to some especially poor eighteenth- and nineteenth-century constitutional and legislative craftsmanship, and it may offer our imperial president a shred of hope for reelection even if he seems to have lost. If we do have the kind of disputed election that forces this system to do its worst, then the silver lining is that surely an aroused populace will demand that the Electoral College be placed where it belongs, in the dustbin of history.