On December 9, 2000, 32 days after Americans cast their vote in that year’s election, Ron Klain allowed himself to believe for a moment that Al Gore might actually become president. Klain was overseeing the legal effort to contest the disputed result in Florida, that year’s decisive state, where George W. Bush held a lead of just 537 votes out of nearly 6 million cast. Bush had already been officially certified the winner by the secretary of State, a loyal Republican, but the day before, in a shocking 4-3 decision, the Florida Supreme Court had ordered a statewide recount.

That morning, a Saturday, the counting got started. All around the state, under the watch of news cameras, election officials visually examined thousands of ballots that, for one technical reason or another, had not registered a vote for president that could be picked up by a machine. There were valid votes in there, and Klain believed Gore was picking up ground fast.

Around lunchtime, as Klain was briefing Gore from his war room in Tallahassee, a call came in on another line. By a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court of the United States had issued an emergency order stopping the recount until it heard the case of Bush v. Gore. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, said that continuing the count threatened “irreparable harm” to Bush “by casting a cloud upon what he claims to be the legitimacy of his election.” There would be a big Supreme Court argument, but it was irrelevant. Gore lost the presidency the day the Supreme Court stopped the count. Klain knew it. Gore knew it. How would Gore react?

Gore picked up his favorite new toy, a technological gizmo called a Blackberry, which he used to send out emails under a pseudonym, “Robert Stone.” Gore tapped out a message to staffers:

“PLEASE MAKE SURE THAT NO ONE TRASHES THE SUPREME COURT.”

“The past is a foreign country,” goes the famous opening line to L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, “they do things differently there.” I have spent this campaign season writing a history of the 2000 election year, hearing the eerie resonances and jarring dissonances. At the time it was happening, the disputed result was considered to be the messiest, most litigious, and most destabilizing outcome imaginable — a stress test the nation passed because, after a long and determined legal fight, the loser declined to challenge the authority of American institutions and conceded.

Like I said, a foreign country.

But there are lessons from 2000 that can be applied to the present unfolding electoral events, ones that will likely shape the legal strategies of both campaigns, in part because many of the same characters are still involved. Klain, of course, is now a top Joe Biden adviser. The Bush effort was a proving ground for an entire generation of Republican legal talent, some of whom have served in the Trump administration, including Noel Francisco, the former solicitor general; Alex Azar, the current secretary of Health and Human Services; some of whom are now in politics, such as Senator Ted Cruz; and three of whom are now on the Supreme Court: John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett.

So, what can the precedent of 2000 tell us about how a 2020 legal endgame might play out?

First of all, let’s start with an obvious difference. At least at this moment — and hey, it could change by the time I finish writing this paragraph — Biden has narrow leads in enough states to give him a very narrow majority of the Electoral College. That matters a great deal. That means Trump is Gore: a candidate seeking to find enough votes to close a narrow gap.

What’s more, Trump faces slender deficits in two states — Nevada and Arizona — as opposed to just one, as in the case of 2000. (In fact, New Mexico’s margin was even closer than Florida’s, so close that it appeared for a moment it might be a tie, which would have triggered an obscure — and I am not making this up! — provision in the state constitution that would have called for the election to be decided by a card game. In the end Gore won by four votes and Bush chose not to challenge it because it would not affect the outcome in the Electoral College.) Complicating Trump’s task even further, he also faces dwindling leads in Pennsylvania and Georgia, placing him in the awkward position of having to play both offense and defense in different states.

If one legal battle for the presidency threw America’s democratic system into cardiac arrest in 2000, it is staggering to imagine what four separate legal battles for the presidency might do in 2020.

On the bright side, at least the campaigns were prepared this time. In 2000, everyone expected a close election, but the idea that litigation — and ultimately the Supreme Court — might end up determining the outcome was inconceivable, at least in the beginning. Both candidates were prepared to accept a defeat. Early on Election Day, Bush received a set of exit polls that suggested — incorrectly — that Gore would handily win Florida, and thus the presidency. He told his daughters it might be an unhappy night. Later in the evening, based in part on the faulty exit-poll data, the TV networks called Florida for Gore. Bush left a family dinner at a restaurant in Austin and rode back to the Texas governor’s mansion with his wife, Laura, in silence. “There isn’t much to say when you lose,” he later wrote in his biography, Decision Points. He wasn’t happy but he was ready to concede.

Then, a few hours later, the projection for Gore was reversed. At 2:16 a.m. on the morning after the election, the TV networks projected that Bush would be the winner in Florida, and thus the next president. Gore absorbed the news without question — without even phoning his own campaign field staff, which thought the race was still too close to call — and called Bush to concede in a dignified fashion. Then, in one of the famously weird scenes in American political history, Gore’s staff managed to get word of the dwindling margin to him just as he was about to take the stage to give a concession speech. Gore called Bush back, and retracted his concession. But the political damage was done. Most Americans had gone to sleep thinking Gore had lost.

Suffice it to say, no one is going to concede this election for the sake of dignity.

There is absolutely no doubt that, had the will of every person who set out to vote in Florida been counted, Gore and his running mate, Joe Lieberman, would have won the election. Among other things, many thousands of Black voters were disenfranchised before the election, due to an error-filled purge of supposed felons from the registration rolls, and after the election, by a confusingly designed ballot used in Duval County, around Jacksonville. (He also won the national popular vote, but of course, that doesn’t matter.) But the concession had lasting political and legal consequences. From the moment the networks declared Bush president, he retained the presumption of victory, and it was Gore’s job to sow uncertainty about the result.

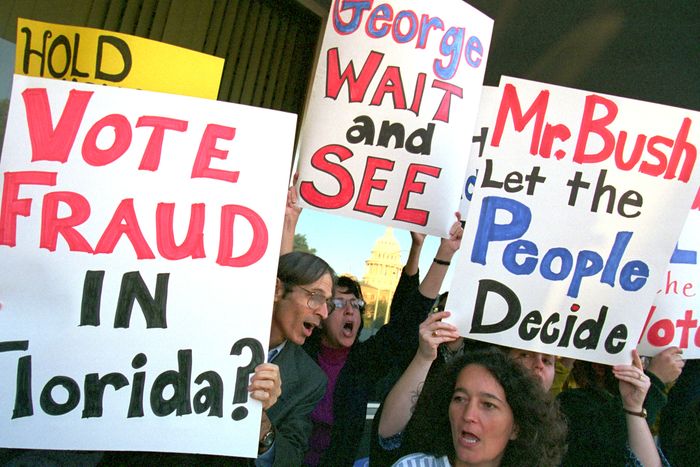

This made him deeply uncomfortable. He was highly conscious of the opinion, widely held among Democratic leaders in Washington and opinion-makers in the media, that he could not appear to be a spoiler. He was concerned about his ability to govern the country. He did not want to create chaos. When the Reverend Jesse Jackson went down to Palm Beach County to mount a street protest over disenfranchisement, Gore asked his campaign manager, Donna Brazile, a protégée of Jackson’s, to call him up and tell him to lower the temperature. Meanwhile, Republican operatives — including, at least in some mysterious capacity, Trump’s now-convicted trickster pal Roger Stone — stirred up unruly street protests in Miami, where there was vociferous anti-Gore sentiment in the Cuban-American community. (Plus ça change.)

The legal consequences of the Gore concession were more subtle. It placed obscure state court judges in the position of having to decide whether to overturn an apparent presidential election result. Understandably, none of them were prepared to take on that kind of responsibility. And the concession also set an artificial clock, of sorts, in the minds of Gore and his advisers — a notion that there was a limit to the public’s patience with the counting. Instead of pressing to count all the state’s votes, they decided it was necessary to pursue a narrow and legally conservative strategy, focused on a relatively small handful of disputed ballots in counties that happened to use an antiquated punch-card voting technology. There were also legal reasons for the strategy, having to do with Florida’s decentralized election system. But cynics pointed out that Gore’s counties just happened to be heavily Democratic ones in South Florida. While Gore’s mantra was “count every vote,” it looked like he was cherry-picking. Republican protesters waved signs reading “Sore-Loserman.”

Meanwhile, bolstered by their presumption of victory, the Bush team showed little compunction about using every legal tool and argument at its disposal, even if it contradicted itself. The Republicans argued that the election was over once the votes were counted on Election Day — except when it came to a thousand or so contested overseas ballots from members of the military that filtered in long afterward, which the Gore campaign suspected had been sent after the election. (There were unsubstantiated rumors that a notorious South Carolina political operative was running an overseas harvesting operation for Bush.) The Bush team argued that the ballots should be processed by machines, not subjective human beings — except in the case of a disputed cache of absentee ballots from Republican strongholds, which had been fiddled with by party workers who corrected innocent mistakes that made them invalid. (A young Amy Coney Barrett worked on the Republican side of that lawsuit.)

Gore would have won the election easily if either set of Republican absentee votes was thrown out. But trying to invalidate some votes, while counting others, would have looked inconsistent. Gore’s lawyers, including David Boies, wanted to bring suits anyway, figuring they were trying to win in litigation, and they had good legal arguments. But Lieberman went on TV and surprised everyone by saying Florida should err on the side of counting military votes.

“Fuck Joe Lieberman,” one of Gore’s staffers in Tallahassee shouted.

In retrospect, it seems clear that Gore’s concern about intellectual consistency, appearances, and public impatience was misplaced. There was never a moment when rank-and-file Democrats turned against him. They really just wanted to win. That is the most enduring lesson that a generation of politicians took from the 2000 election, one that has found its most virulent exemplar in Donald Trump. Thursday morning, presumably referring to Georgia and Pennsylvania, Trump tweeted, “STOP THE COUNT!” Meanwhile, he is pinning his hope for a comeback on a late-breaking surge in the ongoing counts in Arizona and Pennsylvania. Yesterday he sued to stop the vote count in Michigan, where Biden is projected to win. He has announced plans to pursue a recount in Wisconsin.

On the morning after the 2000 election, a jet full of Gore campaign workers and lawyers flew to Florida with little preparation or knowledge of recount law. Most of them had packed clothes for a quick trip — they ended up staying for 36 days. No one involved in the 2020 election disputes has any illusions that they will be over soon. As my colleague Gabriel Debenedetti reported in October, Klain and the Biden team have been getting ready for a post-election legal battle for months. They can take heart from one further lesson of Florida: Even making up a few hundred votes proved to be difficult — ultimately impossible — for Gore. When a consortium of media organizations later did its own unofficial recount of the “undervote” ballots in question in the Supreme Court case, they found that depending on the standard for determining a vote employed, the state recount would have most likely produced little or no gain for Gore. In the best Gore scenario — ironically, under the strictest standard — he won by a margin of just three votes.

By contrast, at the moment, Trump faces deficits of tens of thousands of votes in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Arizona, and (as of this writing) more than 7,000 in Nevada. If the margins hold, a recount probably won’t help. What Trump will likely be looking for, then, is invalidation — throwing out tons of votes on the kind of technicalities that the Gore campaign declined to pursue.

Whether a Supreme Court that now includes three Trump appointees will rule for him, as he has predicted, is anyone’s guess. But if you are curious what basis they might use to override a state’s popular vote, it’s worth looking to the argument in the little-remembered first case before the Supreme Court in 2000, Bush v. Palm Beach Canvassing Board. That ended with an inconclusive decision, but during oral argument, Scalia and Chief Justice William Rehnquist dusted off an 1892 case, McPherson v. Blacker, which found that “there is no color for the contention that” the Constitution establishes an individual “right to vote for presidential electors.” Instead, they suggested, the ultimate power lies with state legislatures, not citizens. Republicans in Florida had actually prepared a bill to appoint a slate of electors, and Governor Jeb Bush had said he would sign it, making his brother president. (You could imagine a similar scenario playing out today in a Republican controlled state like Georgia or Arizona). But that never came to pass in Florida, because Bush v. Gore made the issue moot.

On Tuesday, December 12, 2000, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Bush v. Gore. Gore’s advisers had prepared him for the outcome. “Forget it,” said his campaign chairman Bill Daley, channeling the hardball political culture of his family’s Chicago. “Five Republicans. We’re going right in the tank.” But Gore, being Gore, had allowed himself a little hope in the nonpartisan authority of the institution. He had sat down to write an op-ed column for the New York Times, in anticipation of a ruling that would allow the recount to continue. He concluded with a quotation from Lincoln’s first inaugural address, delivered on the eve of the Civil War:

“Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world?”

Gore’s column was never published, because a ruling came down the evening after the argument, and just as Daley had predicted, it was 5-4. The majority had ruled against Gore based on, of all things, the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, saying that the lack of a uniform standard to decide what constituted a valid ballot meant that the recount privileged some voters over others. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a searing dissent, pointing out that if anyone had an equal protection complaint, it was the thousands of Black voters who had seen their ballots disproportionately invalidated. But the Gore team had downplayed those complaints in its lawsuits and public messaging — talking about voter suppression was equated, in the political culture of the time, with playing the “race card” — and Ginsburg’s friendly adversary Scalia requested that she tone down the “Al Sharpton tactics.”

Ginsburg grudgingly deleted the reference to race.

Bush v. Gore was a muddled opinion, which took some time for Gore’s team to work out on a conference call, but finally they concluded they were out of options. “It may have been wrong to shoot us,” Boies said, “but we’re still dead.” One man wanted to keep going, though: Klain. He refused to give up, and spent the night of the decision drawing up legal papers in the hopes that the Florida Supreme Court might establish a uniform standard, thus satisfying the 14th Amendment problem.

Early the next morning, Gore and his lawyers convened for another conference call.

“Then proceeded the most fascinating kind of historic thing that I have ever been witness to,” Tom Goldstein, an appellate attorney who participated in the Bush v. Gore argument, told me a few years ago. “It was the debate and discussion about whether to adhere to the Court’s decision, which was really, really, really interesting. There was a debate back and forth between the people on the call about whether to fight notwithstanding the Supreme Court, and insist that the Court had effectively tinkered with democracy. It was a real conversation. And it was a real conversation that lasted 20 minutes.”

Finally, the vice-president shut his lawyers down. “It was Gore eventually who just said, ‘No, this is America. We’re done. We’re not going to fight anymore.’”

That evening, Al Gore conceded the election, preserving the legitimacy of the American system of democracy, at least for another 20 years.