On October 23, eleven days before the presidential election, Manohla Dargis, one of the movie critics at the New York Times, popped in to the #newsroom-feedback channel on the company’s Slack to pose an existential query. “Friendly question,” Dargis wrote to more than 2,000 of her colleagues. “What is this channel now?”

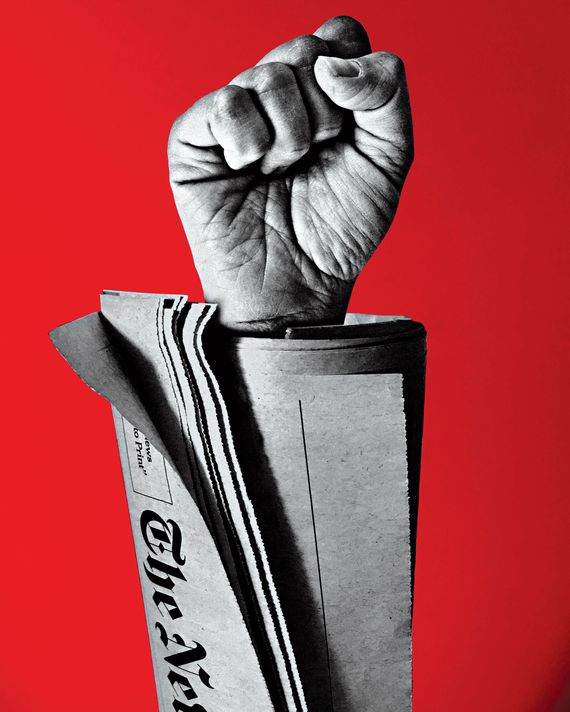

The #newsroom-feedback channel had been created in June, after the Times published an op-ed by Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas arguing for the deployment of the military to quell unrest stemming from nationwide protests in response to the police killing of George Floyd. The column was quickly lambasted: for factual errors, an inflammatory headline — “Send in the Troops” — and a feeling that the Times should not be in the business of publishing arguments for the use of American troops to crack down on American citizens. In response, dozens of the paper’s employees took to Twitter, writing in unison, “Running this puts Black @nytimes staffers in danger.”

This was a break from Timesian tradition, which prohibited employees from expressing their anger at the paper to the broader world. So the staff turned to Slack, taking aim first at the column (“It’s very Bolsonaro of Op-Ed to run this”); then at the op-ed section’s editor, James Bennet (“We’re tiptoeing around the elephant in the room, trying not to notice the stink of the huge pile of crap it’s just dumped. Should JB be replaced?”); and, eventually, at the Times itself. Employees of color felt unheard — “We love this institution, even though sometimes it feels like it doesn’t love us back” — while tech reporters worried the Times’ defense of the column, in the name of an open consideration of a wide range of opinion, was making the paper look like the companies its reporting was taking to task: “It is frustrating to hear some of the same excuses (we’re just a platform for ideas!) that our journalists and columnists have criticized tech CEOs for making.”

In the weeks after the Cotton op-ed, #newsroom-feedback served as a heated pandemic-era office watercooler. This was healthy enough — albeit a distinctly un-Timesian way of handling dissent. The Times had always been a place where employees grumbled in the cafeteria, and complaints might slowly wind their way to the editorial cabal atop the newsroom known as “the masthead,” at which point any decisions would be handed down quietly. Now, Dean Baquet, the paper’s executive editor, was in #newsroom-feedback, answering critiques about the Times’ journalism from not only his reporters but also the paper’s software developers and data scientists.

The conversations could become tense. Employees would paste tweets criticizing the paper into the channel; the journalists would get defensive; someone would leak the argument to friends with Twitter accounts; and the ouroboros of self-criticism would take another bite out of its tail and everyone’s time. “Gang, it would be great to shift the tone of this discussion,” Baquet jumped in to say during a fight about whether “Opinion”-section provocateur Bari Weiss’s description of a “civil war inside The New York Times between the (mostly young) wokes [and] the (mostly 40+) liberals” was a reductive argument, a mischaracterization — or perhaps an unwelcome assessment with a modicum of truth.

The dustup laid bare a divide that had become increasingly tricky for the Times: a large portion of the paper’s audience, a number of its employees, and the president himself saw it as aligned with the #resistance. This demarcation horrified the Old Guard, but it seemed to make for good business. “The truth can change how we see the world,” the Times declared in an advertisement broadcast at last year’s Academy Awards, positioning itself as a bulwark in an era of misinformation.

On Election Night, as the Times’ polling appeared to have overestimated Democratic response, subscribers experienced a partial repeat of 2016’s anguish about whether they were living in a bubble. Four years of upheaval and a summer of unrest, followed by the looming end of the Trump administration, had some inside the paper wondering the same thing. Was whatever might have been lost in the course of the Trump era gone for good — and good riddance?

The Times has a fitful relationship to self-examination. After the Jayson Blair plagiarism scandal of the early aughts, it created a public-editor position to answer questions and critiques from readers, only to discard it in 2017, partly with the idea that Twitter could do the same job. The paper also created a standards department responsible for making sure the hundreds of pieces of journalism it publishes every day, in an increasing range of mediums, remain appropriately Timesian. The department now has its own Slack channel, where editors and reporters can ask whether it’s acceptable to use the word poop in a story about feces being tested for COVID-19 (verdict: “Best to avoid”) and how to decorously describe a recent Zoom incident at The New Yorker (“Less is more in display type”).

The Trump era forced a rushed period of reflection. “I was part of the discussion with Dean when we first described Trump as lying on the front page,” Carolyn Ryan, one of 14 masthead editors at the Times, told me recently. “It took 45 minutes.” The incident happened in September 2016, when Trump renounced his own birtherism, then falsely accused Hillary Clinton of starting the conspiracy theory. “It feels kind of quaint,” Ryan said of the decision. “But at the time, it was a shattering departure.”

It was also a shattering departure for Times journalists to walk into the newsroom after Trump’s 2016 victory and find their colleagues in tears. A neutral objectivity had long been core to the way the paper saw itself, its public mission, and its business interests (Abe Rosenthal, a legendary Timesman, had the words HE KEPT THE PAPER STRAIGHT carved on his tombstone), even if it was an open secret that the Times was published by and for coastal liberals. In 2004, the paper’s first public editor, Daniel Okrent, answered the headline above one of his columns — “Is the New York Times a Liberal Newspaper?” — in the first sentence of his story: “Of course it is.”

At an all-staff meeting shortly after the 2016 election, Baquet told the paper’s staff that it could not become part of the “loyal opposition” to Trump. The Times would report on Trump aggressively — the paper earmarked an extra $5 million to cover the administration in 2017 — but fairly, so that the paper could maintain its “journalistic weapon,” as one of its star writers put it to me, meaning the ability to publish something like Trump’s tax returns and have them be viewed as unbiased truth. “Some read it and like it. Some read it and don’t like it,” Richard Nixon said of the Times. “But everybody reads it.”

Trump presented the newsroom with a series of unprecedented questions. Do you call out his racism in a headline? The masthead’s answer was, in short: Yes, albeit sparingly and with purpose.

But the paper’s claim to holding the independent center was already slipping, as the staff came to grips with an increasingly polarized audience. Journalists were caught between the desire to appear objective to right-leaning readers and sources — while avoiding backlash from left-leaning ones — and wishing they could get back to the job they thought they had signed up for. Most of the pressure to serve as the loyal opposition was coming from the outside: A Pew poll found that 91 percent of people who consider the Times their primary news source identify as Democrats, roughly the same as the percentage of Fox News viewers who identify as Republicans. In August 2019, the paper ran a front-page headline — “Trump Urges Unity vs. Racism” — that caused enough uproar on the left about reputation laundering on the president’s behalf that it was eventually changed to “Assailing Hate But Not Guns,” at which point the president himself joined the fray. “ ‘Trump Urges Unity Vs. Racism,’ was the correct description in the first headline by the Failing New York Times,” he tweeted. “Fake News - That’s what we’re up against.”

But the Timesian impulse toward some kind of objectivity ignored the fact that the view from nowhere was actually too often a view from the Upper West Side and Montclair, New Jersey. “The whiteness of the paper has sometimes been a problem because it makes a bunch of nonwhite people run around like Cassandras — that’s what 2015 and 2016 felt like,” Wesley Morris, the paper’s critic-at-large, told me recently, noting that many employees of color were perplexed by the paper’s initial reluctance to call out Trump for his most brazen expressions of authoritarianism and racism. “Watching that awareness change in four years has been really interesting,” said Morris.

When the Cotton op-ed was published in June, the Times was already “a tinderbox,” as one Black employee said to me. Everyone had been stuck inside for three months, and Black Lives Matter protests were now rolling across the country. White Fragility and How to Be an Antiracist were surging toward the top of the Times’ best-seller list. More than 500 Times employees signed up for what one of the organizers called “Brave Space” events — a recasting of the phrase “safe space” — set up by the Black@NYT employee-resource group to talk about equity, allyship, and self-care in an incredibly stressful time for many.

Cotton’s column lit a match. During a company town hall two days later, while Bennet got teary answering questions, employees took to Slack again to express their frustration at the company’s seeming lack of action to rectify the situation. Bennet had joined the Times in 2016 with an explicit mandate to expand the voices in the op-ed pages beyond the center-left consensus in which most of its columnists fit. The “Opinion” section had suffered a number of controversies, and the newsroom had become frustrated with what seemed to be an alternate set of standards. Employees were galled to find out that Bennet had not read the column before it was published — while a Black photo editor had done so and objected to no avail. A development editor connected Cotton’s op-ed with a profile of Adolf Hitler from 1922, while an employee in brand marketing asked why Alison Roman, the food writer who had recently been suspended for disparaging comments she made about Chrissy Teigen and Marie Kondo, was seemingly being treated more severely than Bennet.

The conversation turned into what more than one Times employee described to me as a “food fight.” During the mêlée, “Opinion” columnist Elizabeth Bruenig uploaded a PDF of John Rawls’s treatise on public reason, in an attempt to elevate the discussion. “What we’re having is really a philosophical conversation, and it concerns the unfinished business of liberalism,” Bruenig wrote. “I think that all human beings are born philosophers, that is, that we all have an innate desire to understand what our world means and what we owe to one another and how to live good lives.”

“Philosophy schmosiphy,” wrote a researcher at the Times whose Slack avatar was the logo for the hamburger chain Jack in the Box. “We’re at a barricades moment in our history. You decide: which side are you on?”

By Monday morning, Bennet was out. To those who saw the op-ed as one in a series of screwups, Bennet’s ouster was a long time coming. To those who believed his effort to present occasionally controversial views for public consideration was core to the Times’ mission, the decision was a retreat from principle. “I call it a fucking disgrace,” said Daniel Okrent, the former public editor. “I think that James’s firing was as meaningful for how the paper is perceived as Jayson Blair was.”

In the weeks that followed, one “Opinion” staffer told me it felt like no one at the Times got any work done at all. There were focus groups — 38 of them and counting — and working groups and innumerable conversations about what the paper should be and look like and who it was for. The masthead started holding “Black-people meetings,” as one Black employee put it to me, in which members of the masthead talked one-on-one with employees of color to sort out why they felt the Times was an unwelcoming place. In #newsroom-feedback, there were many days in which several people were typing.

The gears of institutional change were slowly churning, as they had before. The Times had long been a relative monoculture: Ivy League–educated white people writing for their cohort. Some blamed this bubble on the paper’s dismissal of Trump in 2016 — not that any other mainstream media outlets had done any better. Since then, as business boomed in the Trump era, it had gone on a newsroom hiring spree, with a particular focus on trying to diversify its ranks: 40 percent of newsroom employees hired since 2016 have been people of color.

Several Black employees told me that the Times was the most diverse newsroom they had ever worked in, but simply hiring more young Black reporters wasn’t a cure-all. “There’s a pipeline problem,” one Black staffer told me. The newsroom joke, one reporter said, was that the masthead farmed diversity and inclusion to the softer sections of the paper — “Styles,” “Arts & Leisure,” The New York Times Magazine — so that “they could hire any white guy they wanted in D.C.” The paper’s more senior ranks were less diverse; it seemed to have structural problems that were limiting the promotion of Black employees. A newly instituted performance-review process gives every Times employee one of six ratings; the lowest is reserved for employees who don’t meet expectations, with the other five in ascending order, from “Partially Meets Expectations” to “Substantially Surpasses Expectations.” A study conducted by members of the Times’ editorial union found that in 2019 Black and Hispanic employees received 33 percent of the former rating, despite making up only 16 percent of the staff, while receiving less than 5 percent of the highest rating.

Everyone I spoke to at the Times thought the place needed to diversify: more Black journalists, more Evangelical Christians, more Cuban émigrés, more “people who grew up on ranches who aren’t Nick Kristof,” as one put it. The racial-justice reckoning that shook the nation this summer brought a new urgency to the effort. Managers were required to attend unconscious-bias training. The Times Magazine commissioned a diversity study of bylines and subject matter “to quantify what everyone already knows,” as one staffer put it. The Times gave employees the day off on Juneteenth, which marks the emancipation of America’s slaves. The efforts felt sincere, but everyone knew the road to real change would be long. All employees could do was sigh when one masthead editor explained, in a town-hall meeting, that the paper’s diversity study was being led by Ivy Planning Group, a consulting firm named for the fact that its three founders all went to Ivy League schools.

What the paper did have — in increasing numbers in fact — was a growing cohort of people who came to the paper with a different set of values. They were younger, which produced some of the division. A reporter who identified as “young Gen X” warned me about “toxic millennial workplace values,” while a millennial complained about the masthead’s tortured relationship to social media by arguing that “boomer is a mindset.”

But the most meaningful divide in the newsroom seemed to be by temperament. “The fundamental schism at the Times is institutionalist versus insurrectionist,” a reporter who identified with the latter group told me. (Almost all of the dozens of Times employees I spoke to for this story requested varying degrees of anonymity; one told me, “You can refer to me as a ‘woke millennial reporter’ or whatever.”) The institutionalists were willing to play the internal Game of Thrones required to ascend the masthead because they never wanted to work anywhere else. The insurrectionists, meanwhile, had often come from digital outlets or tech companies or advocacy groups and could imagine leaving the place at any time. (The newsroom noticed that some employees of “Wirecutter,” the most capitalist arm of the Times’ editorial operation, appeared to be the most socialist on Slack.) “I love my job. I like my co-workers. But it has not been my goal since I was 12 to work for the New York Times,” the “woke millennial reporter” told me. “I’m not so blinded by how great the place is that I’m going to ignore the problems.”

Many of the insurrectionists were coming from places the Times didn’t traditionally recruit from, like new digital-media companies and outlets that practiced advocacy journalism, and part of the challenge had become integrating those employees into the Timesian way of operating. “There’s a generation at the Times that’s kind of been raised by wolves, by Times standards,” one institutionalist told me. The new recruits were brought in to help supercharge the company’s efforts at modernizing its news operation, but the Times hadn’t fully understood what it would mean to have a new breed of journalist inside the building. “We set out to diversify the newsroom, but didn’t say, ‘Isn’t the next step to take what these new voices have to bring?’” Baquet said on the Longform podcast this summer. “We started hiring from BuzzFeed; we started hiring from other places, and it was almost like we thought, Okay, now they’re just going to become just like us.”

Of all the fronts on which the Times was being pushed to change, the strongest insurrectionary energy was coming from legions of newsroom-adjacent employees in digital jobs that didn’t exist a decade ago. The employees responsible for distributing the Times in the past — typesetters, pressmen, delivery drivers — had never been encouraged to speak up about the ethical questions at the heart of the paper’s journalism. But the app developers and software engineers who deliver the Times’ journalism to the world have held their hands up in just as many Ivy League seminars as their editorial peers. They might be too shy to march over to a masthead editor and complain about a clumsy headline, but #newsroom-feedback had opened a digital door to criticism. Reporters found that suddenly it was the Times’ programmers and developers, rather than their editors, who were critiquing their work. During the town hall about the Cotton op-ed, one data engineer said on Slack, “How many such process failures would be tolerated in tech?”

Many of the techsurrectionists had come from Facebook or Uber or Amazon to join the Times out of a sense of mission, leaving the ethical quandaries of the tech industry for what they thought were more virtuous pastures. “I joined the company for one reason, and it’s because I feel a responsibility to be a part of a mission that I believe in,” a product manager who previously worked at Apple wrote in #newsroom-feedback after the Cotton op-ed. “This feels like the rug’s been pulled out from under us — not just because it feels like that mission [has] been severely compromised by the decision to publish this piece, but even more so because the products we’re building were used to do it.”

“It’s like making telephone poles,” one software engineer added, “and finding out they’re being used as battering rams.”

Everyone in the newsroom recognized that they were beholden to the techsurrectionists, who didn’t seem to understand the messy humanness that went into the Times’ journalism, but did hold the keys to its business future. “We are competing for talent with the Googles and Facebooks, and what we have to offer these smart, talented people is our mission,” Carolyn Ryan told me. “Now, we’re at this inflection point where people to whom we have said ‘Come be part of this mission’ also want to raise their hand when they’re upset about why we’re not covering a story the way MSNBC is covering it.” But as the election approached, and the news cycle continued at its unceasing pace, and the techsurrectionists continued lobbing critiques at the journalists, the newsroom started to snap back. In mid-September, when a software engineer posted an article from The Atlantic arguing that the media had learned little from its 2016 mistakes, several of the paper’s senior reporters jumped in. “This channel has been a good place for specific, constructive feedback,” Matt Apuzzo, an investigative reporter, replied. “But essentially dropping an all-staff retweet of broad-brush media criticism doesn’t feel productive.” Baquet, along with more than a dozen others, appended a thumbs-up Slackmoji to the comment.

It is difficult to think of many businesses that have benefited more from Donald Trump’s presidency — aside from the Trump-family empire — than the Times. After Trump’s election, in 2016, subscriptions grew at ten times their usual rate, and they have never looked back. The Times has gone from just over three million subscribers at the beginning of the Trump presidency to its record of more than 7 million last month. It has hired hundreds of journalists to staff a newsroom that is now 1,700 people strong — bigger than ever. Its stock has risen fourfold since Trump took office, and the Times has consolidated its Trump bump into a business that includes Serial Productions, the podcast juggernaut; Audm, the audio-translation business; and a TV show based on the Times series “Modern Love” that was filming its second season this summer, until a COVID-19 false positive on-set forced it to halt shooting. More than a million people subscribe to its Crossword and Cooking apps alone, and the company has been able to weather the pandemic in part because it now has more cash on hand—$800 million—than at any point in its history. It has become the news-media organization to rule them all. (A few disclosures that illustrate the point: I’ve written for the Times; I have friends who work at the Times; I recently wrote a book that was reviewed by the Times; I’m a member of the same union as the Times’; and, until recently, I owned a small chunk of Times stock that I bought for $300 in the early 2010s as a bit of performative investment in the importance of journalism.)

A.G. Sulzberger, the newest member of the family to serve as the Times publisher, has rejected the premise that being part of the resistance is good for business, much as Baquet has rejected that impulse in the newsroom, but the business side has leaned into its role as a defender of truth. Identifying as a reader of the Times has become a marker of resistance, and parts of the paper amount to service journalism for participatory democracy — even if the journalists doing the work don’t see it that way. “There’s still this huge gap between what the staff and audience and management want,” one prominent Times reporter said. “The audience is Resistance Moms and overwhelmingly white. The staff is more interested in identity politics. And management is newspaper people. There’s an impulse to want to be writing for a different audience.”

What the audience wants most of all, apparently, is “Opinion.” On a relative basis, the section is the paper’s most widely read: “Opinion” produces roughly 10 percent of the Times’ output while bringing in 20 percent of its page views, according to a person familiar with the numbers. (The Times turned off programmatic advertising on the Cotton op-ed after some employees objected to the paper profiting off the provocation.) Now that the paper has switched from an advertising to a subscription-focused model, employees on both the editorial and business sides of the Times said that the company’s “secret sauce,” as one of them put it, was the back-end system in place for getting casual readers to subscribe. In 2018, a group of data scientists at the Times unveiled Project Feels, a set of algorithms that could determine what emotions a given article might induce. “Hate” was associated with stories that used the words tax, corrupt, or Mr. — the initial study took place in the wake of the Me Too movement — while stories that included the words first, met, and York generally produced “happiness.” But the “Modern Love” column was only so appealing. “Hate drives readership more than any of us care to admit,” one employee on the business side told me.

While Bennet’s impulse was for the op-ed pages to publish a wide range of views that challenged the paper’s readership, it dovetailed with the business side’s goals. “A.G. was absolutely James’s partner in bringing in a wider range of voices,” Jodi Rudoren, a masthead editor who left the paper last year, told me. “The first few times James got in hot water, A.G. said, ‘This was my co-decision.’ ”

By definition, Sulzberger is an institutionalist, but he has served at times as the paper’s most senior insurrectionist. He famously steered the Times’ Innovation Report, in 2014, that pushed the paper’s digital transformation, and well before this summer, he had pushed efforts to diversify the paper’s staff.

This summer, Sulzberger met with several groups of employees to talk about what it would mean to reimagine “Opinion” — although many people at the paper pointed out to me that figuring out what to do in the “Opinion” pages was a perennial problem. Everything was on the table. Don’t take columns from powerful people who already have a platform. Hire more fact-checkers. Publish less often. The one change that wasn’t seriously considered was tearing down the wall between the newsroom and “Opinion” entirely, never mind how blurry it had already become. Editors and writers moved back and forth between the sections — James Dao, the editor who handled the Cotton op-ed, moved to the “National” desk. “Opinion” writers had been doing more reporting of their own, at Bennet’s behest, while newsroom reporters regularly filed “News Analysis” pieces. Why hold on to a line that’s constantly crossed? Tradition, for one. “A.G. is a younger person himself, and wants to be seen as someone who is making that change,” a Times staffer who is friendly with Sulzberger said. “But he also has the weight of the legacy. If he were to go, ‘There’s no news and opinion divide anymore,’ then he’s not just changing the furniture; he’s redoing the blueprint.”

In the meantime, the section sometimes ran into the same problems. Last month, “Opinion” published a column by a Chinese government official arguing for the country’s military crackdown in Hong Kong. It was a virtual repeat of the Cotton situation. The #newsroom-feedback channel lit up briefly, but the conversation was muted. “The China op-ed didn’t hit home because everyone is exhausted,” one Times reporter told me. “You can’t be mad all the time.” Everyone agreed that broader reforms would have to wait until after November.

As Dean Baquet thought through how the Times should adapt to covering the unprecedented nature of the Trump era, he has often talked about interrogating what is core to the Times’ journalism versus what had been done out of habit. This summer, several masthead editors convened a working group to sort out how concerns about diversity intersected with how the paper’s journalism works. Even some of the insurrectionists, who felt the paper needed to diversify and change in various ways, told me that doing so was hard. “The complainers are always right,” one editor told me. “But, as someone who has complained a lot professionally in my life, the solutions are hard.”

As just one example of the ways Times journalists were struggling to adapt, many told me they were grappling with how much of themselves they were supposed to be bringing to work. The Times had put its journalists front and center in the paper’s branding and, increasingly, in the production of its journalism. After a survey revealed that many readers didn’t even realize its reporters were actually on the ground reporting from Afghanistan and Iraq, the Times made a decision to include more first person in its foreign reporting. The artwork for Caliphate, a podcast about an ISIS recruit, hosted by Rukmini Callimachi, a star Times correspondent, featured Callimachi’s face; the paper is now conducting an investigation into whether the central premise was fabricated. Twitter presented innumerable headaches, with reporters having to be chastised for being overtly political, or simply for sounding un-Timesian in their pursuit of likes and retweets. “There’s a very sad need for validation,” one Times journalist who has tweeted tens of thousands of times told me.

Some of the trickiest jounalistic questions have centered on what the Times is or isn’t willing to say. After Bennet’s ouster, Sulzberger met with a columnist for the “Opinion” section who had expressed consternation about the decision. Sulzberger promised the columnist that the Times would not shy away from publishing pieces to which the Times’ core audience might object. “We haven’t lost our nerve,” Sulzberger said.

“Yes, you have,” the columnist told Sulzberger. “You lost your nerve in the most explicit way I’ve ever seen anyone lose their nerve. You can say people are still gonna be able to do controversial work, but I’m not gonna be the first to try. You don’t know what you’ll be able to do, because you are not in charge of this publication — Twitter is. As long as Twitter is editing this bitch, you cannot promise me anything.”

While Bari Weiss’s description of a young woke mob taking over the paper was roundly criticized, several Times employees I spoke to saw truth to the dynamic. They scoffed at the idea that Cotton’s op-ed had put Black employees in danger, and were annoyed that the paper’s union had presented a list of demands that included a more formalized process for sensitivity reads on stories before they were published —a union representative said they just wanted to make sure employees are compensated for doing this work — wishing that the union would stay out of editorial issues and focus more squarely on its upcoming contract negotiation in the spring, when it hopes to reap some benefit from the company’s financial success. This summer, several union members started compiling examples of Times journalism they deemed problematic, intending to present them as evidence of the issues that came with a lack of diversity — only to abandon the effort when someone pointed out that their fellow union members were the ones doing this work. Solidarity was hard for millennials and boomers alike.

But the insurrectionists had plenty to complain about as well. The paper didn’t cover class half as well as it did race, they said; a proposed LGBTQ+ newsletter was considered “tiptoeing into advocacy or activism.” “I have been told, straight up, that I can’t have racist and Trump in the same sentence,” Wesley Morris told me. “Or maybe I can in the same sentence, but not right next to each other.”

The ideological turf war at the Times had become most heated around “The 1619 Project,” a special issue of the Times Magazine focused on centering American history around the lingering stain of slavery, which was then developed into a podcast, a book, an elementary-school curriculum, and the centerpiece of a Times campaign. The groundbreaking project had won a Pulitzer Prize, but had since come under attack, with some questioning its historical accuracy and others probing its ideological intentions — while President Trump used it as a political cudgel. In October, Bret Stephens published an op-ed critiquing the project from within the Times itself, which prompted the paper’s leadership to both approve of Stephens’ attempt at self-critique while backing the project and Nikole Hannah-Jones, its architect, with defensive notes from Sulzberger and Baquet, who called it “one of the most important pieces of journalism The Times has produced under my tenure as executive editor.”

The Times was trying to handle various topics with extra care. Several reporters pointed me to an unusual arrangement in which Carolyn Ryan, one of the paper’s four deputy managing editors, was now editing a trio of reporters that Times journalist described as sharing an impulse toward “poking the bear.” The group included Ben Smith, the paper’s flame-throwing media columnist, and Michael Powell, a 13-year Times veteran who transitioned this year from sports to covering “free speech and identity politics.” Powell was one of the few Times employees who spoke out publicly in favor of publishing the Cotton op-ed in the name of presenting a diverse range of perspectives; his new role included a story about epidemiologists grappling with their willingness to look past the virus-spreading potential of Black Lives Matter protests, and another about the suddenly commonplace deployment of the phrase white supremacy. “It’s constructed as a bit of a third-rail beat,” Powell told me. “I do believe we are hostage to a lot of polarized orthodoxies, and in some way, the New York Times has to be able to address that.”

Ryan was also editing a few stories written by Nellie Bowles, a business reporter with a well-deserved reputation as a dry chronicler of the excessive inanities of Silicon Valley who had veered off her beat this summer to report several pieces that complicated the progressive narrative about the Black Lives Matter protests. One took a critical look at the police-free autonomous zone activists had established in Seattle, and the other followed a group of masked, mostly white protesters who may or may not have been antifa members protesting in suburban Portland. Some of Bowles’s colleagues looked at her reporting skeptically, in part, they told me, because of her relationship with Bari Weiss. The accusation was that Bowles’s reporting had become tinged with her partner’s ideology. One day this summer, a masthead editor was dispatched to deal with a problem that would have been confounding to Abe Rosenthal. Taylor Lorenz, a reporter in the “Styles” section, had tweeted a Bloomberg story about the Seattle autonomous zone that appeared to be a subtweet of Bowles, who had published her own story on the subject a day earlier. A Twitter account with the name 🔥 Burn 🔥 the 🔥 Witches 🔥 had flagged the tweet — “Here comes Taylor with the passive aggressive shot at @NellieBowles” — and Lorenz was asked to apologize to Bowles and respond to 🔥 Burn 🔥 the 🔥 Witches 🔥, assuring an account with 15 followers that there wasn’t any dissension in the ranks of the New York Times.

Ryan’s involvement with the three writers was unusual for an editor on the masthead, an acknowledgment that certain topics required an extra level of supervision to get right. This summer, Ryan had begun holding biweekly meetings with the heads of every department in the newsroom to discuss stories that would fall under the umbrella of “identity.” “Looking at questions of expression and who gets heard and how things get reflected in public debate,” Ryan told me. “There are a lot of ways you could get that wrong.”

In June, during a town hall shortly after the Cotton op-ed, Sulzberger objected to a question from a Times employee about what the paper would do once Baquet was gone and the Times no longer had the shield from criticism that comes with having a Black journalist at the top of its masthead. Both the institutionalists and insurrectionists like and respect Baquet, but both sides were quick to point to the fact that his presence had helped the Times stave off some criticism, in much the same way that Obama’s presidency seemed to convince some portion of America that racism no longer existed. “I don’t think it’s insignificant that we have a Black leader who is a traditionalist,” one prominent white Times reporter told me, of Baquet’s ability to appease both sides.

Per Times tradition, Baquet is expected to retire in 2022, when he will be 66, and it is impossible to talk to a Times employee without the subject of his eventual replacement coming up. Until this spring, three people were considered serious candidates: Joe Kahn, one of Baquet’s top deputies; Cliff Levy, who runs the “Metro” section; and Bennet, who is no longer an option. Kahn and Levy are well regarded but classically Timesian in temperament and background — East Coast raised, white, Ivy League — and it was now unclear if they represented the future. Ryan, who was recently promoted, would be only the second woman in the job and is leading some of the paper’s diversification efforts. Marc Lacey, the “National” editor, is Black and well liked, but he is just as journalistically conservative as his peers. An irony for those looking to add more voice and perspective to their journalism is the fact that the person most inclined to pursue that vision of the Times may have been Bennet.

All of this is guesswork, and Sulzberger, for his part, has expressed little interest in pushing Baquet out the door, according to people who have spoken with the publisher about it. If Baquet sticks around beyond his Times-mandated expiration date, the paper could consider an even wider slate of candidates. “Could Dean hang on long enough to skip over that next generation?” one Times reporter said. “If you’re the queen of England, you skip over your son and give it to your grandson. There’s a potential these princes could be passed over.”

Whoever leads the paper will preside over a media juggernaut forced to look in the rearview mirror at what the Trump era has done to it, and consider where it goes from here. Trump has been a unifying force for the institutionalists and insurrectionists, both of whom object to his assaults on American democracy. The issues being punted until after the election, from diversity to the future of the “Opinion” section, will need to be resolved. The paper is “working on guidance” for Dargis’s question about what #newsroom-feedback should be — good news, because the Times doesn’t expect to have employees back together in a physical newsroom before the Fourth of July holiday next summer. A member of the “Standards” desk was recently promoted to a new position, “director of journalism practices and principles,” meant to help translate the newsroom’s mysterious ways for the non-journalists now supporting their work.

Many people inside the paper think some of its problems could be resolved by bringing back the public-editor position that was discarded just as the Trump administration began. But when I asked Liz Spayd, the last person to have the job, whether she thought reinstating it would make much difference, she wasn’t so sure. “There’s clear benefits to having someone with free rein to report inside the building and to speak for the public,” Spayd said. “But does that translate into the Times listening to that and taking action? Clearly not.”

Change does not come swiftly to the Times. Readers were distressed to wake up on Election Day and find out that the paper was bringing back its infamous needle, and the days that followed were filled with recriminations about how the Times had kept readers in a bubble — never mind that the warnings about the shifting Cuban vote in Florida and the lengthy vote-tabulating process ahead were there in the news pages for anyone who had taken the time to look there, rather than feeding themselves another dose of their favorite “Opinion” columnist. The paper attracted more readers to its website than ever before. As its journalists got to the task of narrating the end-stage of the most extraordinary period of American history in living memory, Joe Biden was promising to bring the two Americas back together. The Times had become the paper of the resistance, whether or not it wanted the distinction. The months ahead will determine whether it can again become the paper of record.

*This article appears in the November 9, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

*This story has been updated to more accurately characterize Sen. Tom Cotton’s op-ed.

**This story has been updated with the most current information about performance reviews at the Times; and to include comment from a union representative about the paper’s procedures for sensitivity reads.