Earlier this month, a bipartisan group of senators reached agreement on an outline for a $908 billion COVID-19 relief package. The Democratic Party’s congressional leadership swiftly endorsed the framework. And, when the authors of the package agreed to split off its two most controversial provisions — fiscal aid to states and a temporary liability waiver for employers — Republican leaders warmed to what was, in effect, a slightly larger version of bills they’d been pushing for months.

Under the bipartisan framework, America’s jobless would have received $300 a week in enhanced unemployment benefits for up to 16 weeks. Gig workers and independent contractors would have also received $300 a week through an extension of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program.

But the bipartisan outline did not include funding for a new round of $1,200 relief payments. Those stimulus checks had been among the most popular and salient features of the CARES Act, and had put vitally needed cash into the hands of many Americans who could not access unemployment benefits, either because of ineligibility or logistical challenges to getting enrolled. Thus, many progressives argued that the final compromise bill must include such checks — while Bernie Sanders joined with Republican senator Josh Hawley in threatening to block the bill’s passage if relief payments were not appended to the legislation.

Negotiators heard this call and adjusted the package accordingly: The latest version provides $600 checks to individual adults (who earn less than $75,000), along with $600 per child or dependent adult within a household. But instead of layering funding for checks on top of the bill’s other provisions, congressional leaders opted to pare back unemployment benefits to finance the relief payments. Now, instead of providing America’s jobless with 16 weeks of enhanced benefits, the legislation affords them just ten.

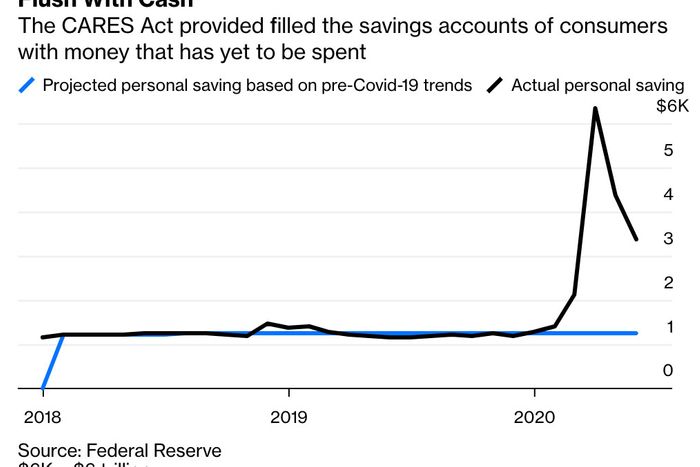

Some policy analysts see this outcome as a left-wing own-goal: Whatever its intention, the effect of a late push for relief checks was to shift a politically fixed pot of money away from the long-term unemployed and toward households that earn up to $150,000 a year. This trade seems perverse to some progressive economists, not least because a significant percentage of households eligible for relief checks are better off financially now than they were at the pandemic’s onset. The unemployment rate among Americans who earn more than $60,000 per year is a percentage point higher today than it was on February 1, according to the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker.

Meanwhile, since most middle-class Americans never lost their jobs during the pandemic — but did receive a stimulus check in the spring, while dramatically reducing their spending amid a giant contraction in opportunities for (safe) travel and consumption — the typical middle-class household appears to have a higher net worth today than it did last year.

The economic pain of the COVID recession is not universally dispersed, but rather, viciously concentrated on a (large) minority of the public. Why then, some analysts ask, should the disbursement of universal checks be a higher priority for progressives than robust aid to the unemployed?

Of course, for Sanders and his allies, the goal was never to prioritize relief payment over unemployment insurance but rather a more comprehensive stimulus package over abstract concerns about the deficit. As Sanders told the Washington Post this week, “I don’t understand how Democrats accepted — when you had [Treasury Secretary Steven] Mnuchin talking about $1.8 trillion and this large Heroes bill — I don’t know how Democrats started accepting a framework of only $900 billion.” Here, the Vermont senator references the fact that before Election Day, Steve Mnuchin had floated a $1.8 trillion relief package that would have included fiscal aid to states and cities, among other things. House Democrats ultimately snubbed that offer, citing its inadequacy relative to the $3 trillion package they had passed back in May. But before November 3, Donald Trump’s reelection campaign stood to benefit from the passage of a relief bill. Today, Joe Biden’s approval rating early next year would likely be buoyed by such aid. Therefore, Democrats seem to believe that their leverage has diminished since earlier this fall (and even back then, it was not clear whether McConnell would support Mnuchin’s offer if Pelosi had accepted it).

Regardless, assuming that progressives can’t force through a larger package, would they have been wiser to accept the initial bipartisan framework over the new one, checks be damned?

This strikes me as a complex question that I don’t have the resources to answer with certainty. But, as far I can tell, the case for taking the checks, even at the expense of unemployment benefits, goes like this:

1) Checks will put cash into the hands of the needy faster than UI will. Unemployment benefits are distributed through 50 different state bureaucracies, many of which are shoddy by design. And since Congress procrastinated so long on extending UI benefits, many states will need to reprogram their systems to dispense further aid. The holiday season is likely to elongate the delay between the passage of new benefits and their receipt by beneficiaries. Which means that many of the long-term unemployed are about to see their income crater amid the darkest winter in modern memory. Although there are logistical challenges to distributing relief checks, the IRS allocated the CARES Act’s payments more swiftly last spring than many state unemployment offices did. As of May, only three in five Americans who’d applied for unemployment benefits had secured them. The second time around, it should be easier for the IRS to rapidly distribute aid. Given the desperation of America’s least fortunate, quick relief is preferable to the well-targeted kind.

2) Checks reach needy people whom UI does not. Relief checks provide direct aid to nonworking Americans who aren’t in the labor force, such as children and the elderly, groups that suffer disproportionately from poverty. For this reason, universal cash payments would do more to reduce poverty, dollar for dollar, than increasing traditional unemployment insurance benefits would, according to research from the UBI Center. That said, the tradeoff here is not between cash payments and traditional unemployment; when combined with PUA, the CARES Act’s unemployment benefits reached a much larger universe of nonworkers than conventional UI.

3) Checks are popular, and serve to make the American public more conscious of the government’s capacity to directly help them. One recent poll put support for another round of stimulus checks at 70 percent. The popularity of the policy is inseparable from its lack of targeting: Because the relief was not concentrated on the needy, the constituency for doling out more aid is unusually large. Doing popular things isn’t an end in itself. But it’s possible that a second round of stimulus checks will make the first one feel less like a one-off aberration, and more like “what the government does when times are tough.” Given that American progressives have long found it politically difficult to provide unconditional cash assistance to the poor — and to persuade the median American that the government can in fact intervene in the economy to make their lives easier — there may be a long-term political upside to normalizing the periodic distribution of relief checks to a majority of Americans.

4) If Democrats win in Georgia, they can simply extend the duration of the unemployment benefits. Finally, if Democrats sweep the Senate runoff elections in Georgia next month, they’ll secure a Senate majority and, thus, the power to extend unemployment checks for whatever duration they choose.

Nevertheless, absent further legislation, America’s long-term unemployed will be worse off under the current stimulus framework than they would have been under the original bipartisan one. Ideally, Democrats will leverage the current bill’s inadequacies into a Peach State triumph in January, and pass a more comprehensive relief bill shortly thereafter.