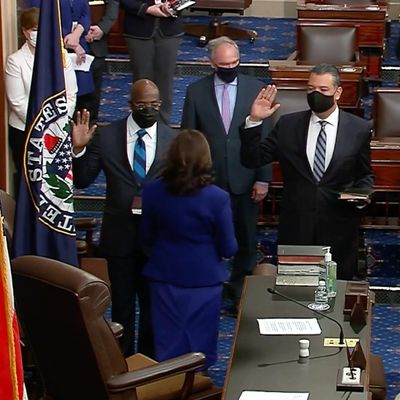

Though it’s being understandably overshadowed by Joe Biden’s inauguration and Donald Trump’s departure, Democrats are also cheered today by the swearing in of new Georgia senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, which in combination with Kamala Harris’s ascension to the vice-presidency flips control of the Senate to Democrats.

There has already been some jockeying between outgoing Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and his successor Chuck Schumer over a “power-sharing” agreement so that Harris doesn’t have to spend most of her time breaking ties in the Senate, with McConnell demanding (and so far not securing) assurances that Democrats won’t zap the legislative filibuster, the main source of Mitch’s power. And we have been reminded of a previous arrangement the last time the Senate was equally divided between the parties.

But there is another bit of history Democrats would be wise to think about at this moment of celebration. The Senate flip gives them a governing “trifecta” with control of the White House and both houses of Congress. The last two times they enjoyed this position were in 1993, when Bill Clinton became president, and in 2009, when Barack Obama and his trusty sidekick Joe Biden were inaugurated.

In both cases, things did not turn out that well the next time Democrats faced the voters. The Republican landslides of 1994 and 2010 ended a lot of early Clinton and Obama administration ambitions. The 1994 midterms put the House out of reach for Democrats for 12 years and the Senate for the same length of time, except for a brief interregnum in 2001 and 2002. And while Democrats had too large a Senate majority to lose control of that chamber in the 2010 debacle, they lost the House for eight years and eventually lost the Senate in 2014 and the White House two years later.

Yes, the midterm losses Democrats experienced after winning trifectas were in some measure cyclical in nature: Republicans lost their own trifecta, after all, in 2018, and only twice since 1934 has the party controlling the White House made gains in midterm House elections (in 1998 and 2002, as it happens). But the quick Clinton and Obama setbacks offer a cautionary tale for today’s Democrats: With the narrowest possible margin in the Senate and only a four-seat margin of control in the House, even a mild Republican midterm wave in 2022 could disrupt all the Biden administration’s plans while putting a rude end once again to any notion of an enduring Democratic governing majority. The best news for the Donkey Party is that the 2022 Senate landscape looks manageable, and the combination of relief from the chaotic atmosphere of the Trump presidency and the prospect of an end to the COVID-19 pandemic could give the governing party an unusual midterm lift.

Joe Biden, obviously, experienced these moments of triumph followed by defeat and disappointment; he was near the seat of power in the second cycle and had a mixed record at best in the assignment Obama gave him to implement a legislative agenda despite Republican obstruction the first two years and Republican power for six more. He was part of a presidential ticket that bounced back from the 2010 debacle to win a second term. He’s been here before and will face the same inevitable trade-offs between quick but unpopular accomplishments and future electoral successes. Now as before, the thrill of victory could fade very quickly.