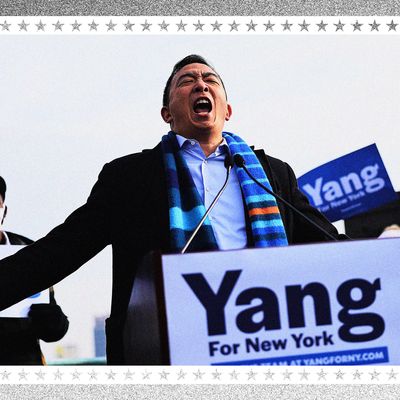

When Andrew Yang dropped off his petition signatures at the Board of Elections on Tuesday morning — something all candidates must do to appear on the ballot — he ran through a gauntlet of supporters, slapping elbows all the way. He announced to the crowd how many he had gathered (more than 9,400) by signing it to the tune of “Seasons of Love” from the musical “Rent”: “How many signatures could you get in a year?” He dared anyone there to feel exactly how much all those petitions weighed, as cameras clicked and reporters live-tweeted the spectacle.

Yang wasn’t the only candidate to invite the press to watch him drop off his signatures, and the total number he gathered was smaller than that of many others in the field, a few of whom submitted over 20,000 signatures. But he was the only one to turn what is usually a dry ritual before a municipal bureaucracy into an event, getting the kind of coverage that the rest of the field no doubt envies as each candidate rolls out high-profile endorsements and ambitious policy positions to an audience of almost no one.

Yang entered the race for mayor two and a half months ago. Few political insiders thought he would last. Conventional wisdom had him getting eaten up by the press corps after showing how little he knew about New York City and its government, failing to impress the union bosses and political leaders who yield power in this town, and probably getting bored along the way. The first poll of the race was in the field more than a month before Yang got in the race; he led that one. The same conventional wisdom tended to discount this as a short-lived state of affairs, based purely on his fame as a presidential candidate. But he has continued to lead in every other poll since, often by a fairly sizable margin. He raised over $6.5 million in just 57 days, with more New York City donors than any other candidate, even those that have been raising money for years. There are now less than three months until Election Day. Which raises the question: If Yang is going to be stopped from becoming the 110th mayor of New York, what is going to stop him?

Yang’s rivals insist that his decline is still imminent, that his numbers are soft. One person working for a rival camp told me that its poll numbers show that half of Yang’s supporters can’t say why they are voting for him, evidence that his lead is more a function of his name ID than of actual support. “Nine out of ten voters know who he is, and he is at 25 percent. Half of them think of him as the free-money guy. That is a bigger problem than his campaign lets on.”

Pollsters say that voters aren’t really paying attention to the race yet. There has been a lot for the news-consuming public to pay attention to lately: a Capitol insurrection, a peak in COVID cases and mass-vaccination rollout, a $1.9 trillion recovery package, and, of course, the ongoing sexual-harassment and nursing-home-deaths scandals involving Governor Cuomo. Some evidence supports the theory: A new survey showed that half of New Yorkers have not made up their mind. Operatives think that most voters won’t start focusing on the race until April or May. The history of recent mayoral primaries show one candidate hitting their stride with sometimes just a month to go and upending the race. In 2013, Bill de Blasio wasn’t consistently leading the polls until three weeks before Election Day; in 2005, Anthony Weiner jumped 15 points in the final two weeks to nearly make a runoff.

If the assumption when Yang entered the race was that he wouldn’t know how many boroughs there are in the city or what rezoning is, that hasn’t quite happened. But he has made a series of gaffes, which range from the silly (like thinking a well-lit corner store is a bodega) to the more head-scratching, like his suggestion that the city should build a casino on Governors Island, even though federal law prohibits it. None of those have dented his standing yet, and it is hard to guess when they will, since owing to the city’s campaign-finance system, Yang’s rival campaigns are unlikely to be doing much advertising against him until at least the beginning of May.

But the attacks are coming. Campaigns have discussed eschewing the traditional bio spots introducing candidates to the public in favor of going after Yang — a sign of how much his rivals have been unsettled. “He’s going to be getting it from all sides, and it is very hard to defend yourself from that,” said one operative working for a rival campaign. Because the campaigns are limited by how much they can spend, several are hoping that a super-PAC funded by wealthy supporters of Ray McGuire, himself a former Wall Street executive, will mostly focus on attacking Yang rather than pumping up McGuire. But there is no evidence yet that Yang, a center-left candidate with a long background in the business world, is particularly worrisome to New York’s elite.

In recent days, some of Yang’s rivals have decided not to wait for help, going after the candidate directly. When Eric Adams was endorsed by 32BJ, one of the most powerful unions in the city, he referenced Yang’s fleeing the city for New Paltz during the height of the COVID pandemic. “Don’t make me pull out the milk carton with your face on it saying you was missing when the city needed you. I am not MIA,” Adams said. At a recent Zoom forum, both City Comptroller Scott Stringer and McGuire eviscerated Yang’s signature plan for universal basic income, and at a recent speech before the august Association for a Better New York, Stringer unloaded on the front-runner for disparaging the teachers union for slowing school reopenings. “I don’t begrudge Mr. Yang making decisions that he felt were best for his family,” Stringer said, another reference to the Yang Family Country Home. “But he clearly doesn’t understand what so many went through, and the least he can do for our teachers is to take the time to learn, and show them some respect as the front-line workers they are. The truth is that this is par for the course for Mr. Yang — whether it’s an illegal casino on Governors Island, housing for TikTok stars, or being baffled by parents who live and work in two-bedroom apartments with kids in virtual school. We don’t need another leader who tweets first and thinks later.”

The speech stunned the other campaigns, but it showed exactly where Stringer and the rest think Yang is vulnerable — that he is an unserious person who lacks city ties, a striver consumed with personal ambition who would come to City Hall with no government experience and a thin record of business success. “Every negative story that has been written about him so far is going to be strung together in every ad in May and June, and it is all going to be about: This is a serious time. Do you really want this guy in charge?” the rival operative said. “I think New Yorkers understand that being mayor is a serious job and the way Yang has a slapdash approach to everything is going to be his undoing.”

Yang’s 2020 presidential run, in which he raised over $40 million and netted zero delegates, is likely to come under scrutiny — including allegations of a sexist campaign culture — in the mayor’s race, as Yang’s rivals look for ammunition. “Here is a guy who went away to prep school, who grew up in Westchester and then fled the city in its hour of need. Every ad is going to ask voters if they think he is someone who you recognize, if he is someone who shares your concerns and your struggles.”

The other campaigns believe that while the race has been covered by online and print outlets, eventually local TV will start covering the race, and that, plus the advertising blitz, will get voters to pay attention, and that they will begin asking questions about Yang’s readiness and his background.

Yang’s campaign is aware that this line of attack is coming and are wary of the rest of the campaigns and their union allies and financial backers ganging up them. A “Yang vs. the World” dynamic could complicate the Yang campaign’s desire to be seen as the fresh-faced outsider.

But if Yang is such an inviting target for attacks, it raises the question of why none of the attacks have worked quite yet and, more to the point, when they will start to. Yang’s rivals pounced on him the day he announced, and he’s still the front-runner. Maybe the ads will start running in May, and local TV will tune in to the race, and all of this supposed baggage will be Yang’s undoing, but it’s getting late early out there, and New Yorkers appear to like Yang more than the political class seems to understand.

“New Yorkers want hope and optimism,” said Yang campaign manager Chris Coffey. “The only press the other candidates get is when they complain about us. We understand that this campaign is going to get nasty and negative. We are going to stay positive and focused on getting the city back on track.”

The jibe about the press only being interested in Yang might resonate with rival campaigns. “It blots out the sun,” said one operative, who noted with both pleasure and dismay how eager reporters are to run with the negative stories on Yang.

“I get so many more calls these days from reporters wanting me to comment on Andrew Yang than any other candidate,” said Neal Kwatra, a longtime local campaign operative currently unaffiliated in the race. “It tells me what people are interested in. Yang is driving the race right now. Politics has changed, and I think a lot of people haven’t quite caught up to how.”