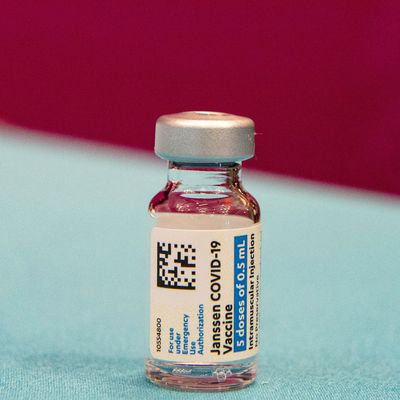

On Tuesday, the FDA and CDC recommended pausing the administration of the Johnson & Johnson COVID vaccine while the agencies investigate an extremely rare possible side effect. Six women in the U.S. who received the J&J vaccine — all between the ages of 18 and 28 — experienced a blood- clotting disorder called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the days after getting their shots, and one has died. It’s not yet clear if the clots were related to the vaccine, though a similar disorder has occurred abroad among some recipients of the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine, which uses the same adenovirus-vector technology as Johnson & Johnson’s. As scientists continue to research the cases to determine if and how they may be related to the shot, U.S. regulators’ sudden decision to pause J&J’s distribution has prompted widespread reaction from across the COVID-expert community. Below is an overview of what they are saying.

Brown University School of Public Health dean Ashish K. Jha called the move “the right step,” arguing that “central to vaccination success is ensuring people have confidence they are safe.” He and many others, including the nation’s top infectious-disease official, Dr. Anthony Fauci, have said the pause demonstrates that the FDA and CDC are being appropriately thorough. The Atlantic’s Katherine Wu spoke with 12 COVID experts after the pause was announced, and they “all struck a similar note”:

The pause is a reflection, they told me, of federal regulation in action — responding to even the tiniest hint of a safety issue, in case it blossoms into something serious. In similar situations, other vaccines have been subject to the same scrutiny; it’s not that uncommon for products to hit roadblocks after initial clearance. “I’m somewhat concerned, but I’m not freaking out,” [Yale vaccine expert] Saad Omer said. With the right monitoring systems in place, investigations like this can and should happen, with transparency. “This is the system working as intended,” Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at the University of Florida who studies vaccine trials, told me. “We’re paying close attention to even these exceedingly rare outcomes.”

James Hamblin, a doctor and journalist who is a colleague of Wu’s, said in a tweet on Tuesday, “Pausing vaccination to look into a possible one in a million side effect may scare people. It could just as easily be seen as reassuring, proof that close attention is being paid to, and extremely high priority put on, vaccine safety.”

As FDA and CDC officials stressed on Tuesday, one critical reason for the move is to alert doctors to the potential problem and make sure they know how to treat it — particularly since one of the standard treatments for blood clots may, in the case of this specific disorder, make it far worse. New York City doctor Craig Spencer underlined that point in a Twitter thread on Tuesday night with a real-world example:

I was in the ER today. One of the first patients I saw after getting briefed on the J&J decision was a young woman in her 30s. She got the J&J vaccine a week ago. She had symptoms that overlap with those we were told to look out for. Today’s announcement changed my differential diagnosis & impacted my clinical management. That’s exactly what it was meant to do. It’s also how we’ll get the data we need.

He added that the regulators’ decision to pause the J&J vaccine “should drastically improve our faith in the public health institutions tasked with protecting us. With how they had been politicized and over-ruled by the previous admin, this is critical. And that’s exactly why I think today’s decision was the right one.”

Former FDA director Scott Gottlieb also cautioned against overinterpreting the move during an interview with CNBC on Tuesday morning: “Let’s start with what the FDA didn’t do: They didn’t revoke the emergency-use authorization; they didn’t order this off the market. This was a requested pause, which is an awkward regulatory step, but it reflects a level of caution on their part not to appear too forcefully here that it becomes hard to unwind this action.”

He added that the pause may be a product of how well the vaccination effort is proceeding, explaining that “we have many more people vaccinated [and] more supply of the mRNA vaccines,” which means the FDA’s risk-benefit calculation on how to proceed in light of the reported blood clots “probably changes in that environment.”

Johns Hopkins’s Tinglong Dai, who has been studying management-and-operations issues during the COVID-vaccine rollout, made a similar point in a Twitter thread, noting that because the U.S. is in an “enviable supply position” and J&J’s vaccine made up only a tiny fraction of the doses being administered and is now experiencing manufacturing disruptions, “it’s an okay timing [for the FDA] to pause and look into what’s going on.”

Gottlieb speculated, however, that the pause would “fuel” hesitancy about the vaccine. Jha said he wasn’t sure about that or whether, as some argued on Tuesday, the move would do more harm than good: “My sense is confidence comes from people believing that we have a vigorous system that takes adverse events seriously. We do. This is how it works.”

In a MedPage Today op-ed, Dr. Tim Lahey argued that a long-game mentality is needed when analyzing the risk benefit of spooking the public:

COVID-19 vaccines confer massive protection from hospitalization and death from COVID-19, not to mention protection from persistent symptoms that have dogged upwards of a third of people afflicted with COVID-19. These benefits come at the cost of common side effects like sore arm, low-grade fevers, achy muscles and fatigue, as well as extremely rare toxicities like blood clots arising from the auto-immune generation of antibodies that activate platelets.

Scientific transparency is similar. Most people are reassured that scientists and regulatory officials are being exceedingly careful with COVID-19 vaccines, including pausing distribution to investigate safety signals. Surely this can drive short-term vaccine hesitancy, but since vaccine hesitancy derives from mistrust of science, trying to hide vaccine side effects will only exacerbate the problem over the long term.

We should tolerate the short-term side effect of temporarily increased vaccine hesitancy in order to derive the long-term benefit of public trust in global efforts to scale up COVID-19 vaccines to protect our loved ones and restore our beloved normal ways of life.

Many experts (and nonexperts) who reacted to the pause on Tuesday tried to emphasize how unlikely it is that recipients of the J&J vaccine will develop a severe blood clot.

Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT, “You have a greater chance of being in a car accident on the way to getting this vaccine than you have of having a problem from this vaccine. But that’s not how people view risk.”

But epidemiologist Caitlin Rivers added that the numbers may look different in the end: “One in a million will not be the final estimate for the unconfirmed J&J events, and I think we should be cautious in citing it.”

Some experts were critical of the FDA’s decision, including Johns Hopkins School of Public Health professor Marty Makary, who tweeted on Tuesday that “the intense paternalism of the FDA [is] vivid right now” and, pointing to the rarity of the blood clots, commented, “If the FDA starts blanket banning things that have [led to] one death in seven million, we wouldn’t have 50 percent of medications and 80 percent of medical devices that we use.”

He and others argued that the FDA’s J&J pause should have been selectively applied to the demographic in which the six cases were observed — women between the ages of 18 and 49 — as well as those already at risk of a blood clot. Indeed, many experts are speculating that the FDA will do exactly that after it finishes investigating the issue next week.

And sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, who has challenged status quo thinking throughout the pandemic, emphasized the communications challenge the news presents. She argued that regulators and those who amplify them need to better account for how this type of news typically plays out, suggesting, “One principle … would be to minimize as much as possible the free-for-all in the news cycle (now at least 48 hours) and be a lot more ‘muscular’ in the announcement — today felt like communication to doctors, rather than the whole anxious world.”