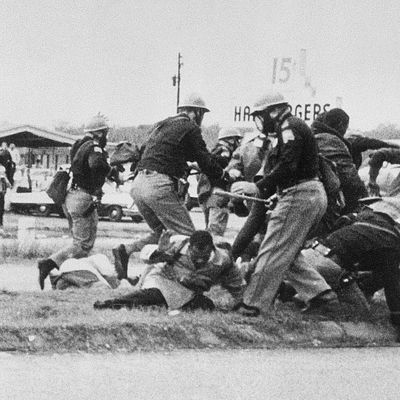

On a strict party-line vote before taking its August recess, the U.S. House passed a revised version (H.R. 4) of the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. The bill is designed to restore provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (itself inspired by Lewis and other protesters in Selma, Alabama, who were brutalized by state troopers during a march for voting rights) that have been gutted by U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2013 and earlier this year. An earlier version passed the House in 2019 but was never taken up by the Republican-controlled Senate.

The bill is often discussed in tandem with another piece of voting rights legislation passed by the House earlier this year, the For the People Act (S. 1), which stalled in the Senate when Democrat Joe Manchin joined all 50 Republicans in opposing it. Manchin and one Republican senator – Lisa Murkowski of Alaska – have in the past supported some version of the John Lewis Act, and Manchin is making it the centerpiece of his efforts to come up with a bipartisan compromise on voting rights. On the other hand Manchin (along with Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema) has ruled out any reform or limitation of the right to filibuster that might enable actual passage of the bill. (It is generally assumed that voting rights measures are not budget-germane, which means they cannot be included in a budget reconciliation bill to sneak past a Senate Republican filibuster.)

Here’s a look at what the John Lewis Act would do, and its chances of ever becoming law.

How does the John Lewis Act differ from the For the People Act?

Descriptions of the two pieces of legislation are often boiled down to the For the People Act as broad and the John Lewis Act as narrow. That’s true, but the bigger difference is that the For the People Act is a highly prescriptive bill that preempts state voting and election laws, mandates many practices (e.g., automatic and same-day voter registration and easily available early voting) and prohibits many others (e.g., unnecessary voter-roll purges and partisan gerrymandering).

The John Lewis Act would create procedural rules governing voting-rights violations. This is similar to Section 2 of the original Voting Rights Act, which established legal grounds for private parties or the federal government to challenge state laws that are intended to, or have the effect of, diluting minority voting rights. (This section was significantly curtailed by the conservative majority of the U.S. Supreme Court this year in Brnovich v. DNC). The far more powerful Sections 4 and 5 created a system whereby jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory practices would have to submit changes in voting and election laws to the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department for review and “preclearance” as non-discriminatory before they could take effect. It was Section 4, which set up a formula for determining which jurisdictions fell under the Section 5 preclearance requirement, that the Court killed largely killed in its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder ruling, claiming it was based on outdated evidence of discriminatory practices.

Since both Supreme Court decisions modifying the VRA were based on statutory interpretation, they are susceptible to a congressional “correction.” The revised John Lewis Act would seek to neutralize Brnovich by emphasizing a right to use Section 2 to address the discriminatory consequences, direct and indirect, of voting and elections changes,

“instruct[ing] courts to consider other discriminatory factors when hearing such cases, including the history of discrimination in the state and the impacts of racism across impacted jurisdictions, from education and employment to health disparities.” And to counter Shelby County it would revise the Section 4 formula for preclearance to cover states with “15 or more voting rights violations” in the previous 25 years, or just 10 violations if “at least one [violation] was committed by the state itself.” This is intended to be a self-updating formula which will keep the courts from future challenges to the law.

Would the John Lewis Act stop the current explosion of state laws restricting voting rights?

Many of the provisions in the state Republican-enacted voter-suppression laws that popped up after the 2020 election would be flatly (and retroactively) prohibited by H.R. 1/S. 1. The John Lewis Act would also stop future laws and procedural changes from taking effect without a Justice Department preclearance. It’s hard to know exactly which laws and procedural changes would and would not pass muster, and it’s worth considering that a future Republican administration might very well reverse pro-voting-rights guidance set down by the Biden administration.

But without question, the John Lewis Act would slow down, and might well inhibit, voter-suppression activity.

Can the John Lewis Act conceivably get through Congress without being filibustered?

The premise of Joe Manchin’s argument for making the John Lewis Act rather than the For the People Act the main vehicle for voting rights action in Congress is that the Voting Rights Act was last extended (in 2006, seven years before the Court gutted it) by a unanimous Senate vote and a Republican president (George W. Bush). Thus legislation to restore it should command considerable bipartisan support. The trouble is, it doesn’t. When the bill passed the House in 2019, only one Republican (Brian Fitzpatrick of Pennsylvania) voted for it. As noted above, no Republicans voted for the new version.

It is true, perhaps, that killing the John Lewis Act would be marginally more embarrassing to the GOP than killing the For the People Act, given the party’s past support for the VRA. But there’s little doubt Republicans will find a way to justify doing it in, by either (a) taking the Supreme Court’s position a bit further and arguing racial discrimination in voting simply no longer exists, or (b) arguing any voting-rights legislation must include “election integrity” provisions addressing their (and Trump’s) phony-baloney fraud claims. “Whataboutism” has become the standard Republican excuse for refusing to do the right thing. So actual passage of anything like the John Lewis Act remains impossible for the foreseeable future, at least so long as Democrats cannot muster the internal Senate support to kill or modify the filibuster.

This piece has been updated.