In mid-September, King County, Washington, in which Seattle is located, released an eye-popping slide about vaccine efficacy and breakthrough prevalence: Vaccines had reduced the risk of infection from COVID sevenfold, county data showed, and reduced the risk of hospitalization and death 41-fold and 42-fold, respectively.

These ratios, though bigger than those found in other studies released in recent weeks, are nevertheless in line with an obvious emerging consensus in the data: Vaccines do clearly reduce transmission and dramatically reduce hospitalizations and deaths, making the threat of severe outcomes to the vaccinated much more like the risk associated with other, far more quotidian diseases. A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study of Los Angeles found a 29-fold reduction in hospitalization from vaccines early this summer, for instance, and another quasi-national study suggested an average 11-fold reduction in mortality risk overall.

But in small type, King County included some other data that paint what seems at first blush like a very different picture: Fully 25 percent of deaths were among vaccinated people, the county reported. How can this be? If the vaccines are so effective that they reduce mortality 42 times over, how could the vaccinated account for such a large proportion of the deaths? The answer is actually quite simple: the overwhelming age skew of the disease, which — in the time of vaccines, breakthrough cases, and Delta — we are still, as a public, hugely underestimating and which is governing the post-vaccine pandemic landscape as clearly as it did the pre-vaccine landscape. To put it more bluntly: in assessing an individual’s risk of dying from COVID, age appears still as important — and maybe even more important — than vaccination status. And while encouraging further vaccination remains by far the best tool we have in fighting the pandemic to an endgame détente, we should also be clear along the way about the continuing risks to the vaccinated elderly and what might be done to protect them.

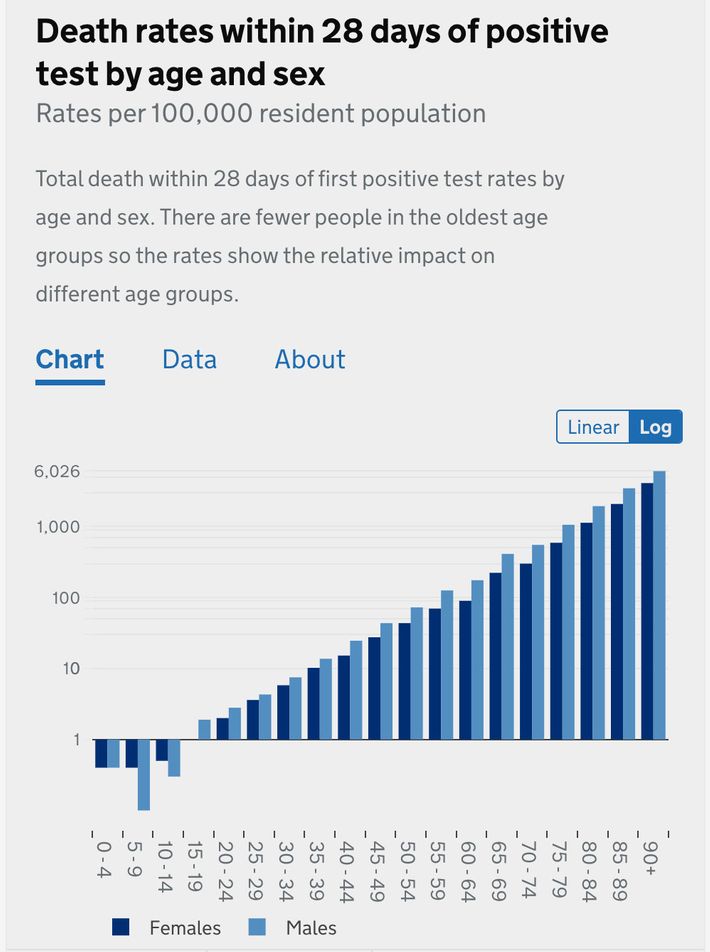

Most people know the pandemic has hit the elderly hardest — that is the meaning of the age skew, that the disease grows much more severe the older you are. But if they have seen a chart illustrating this, it probably looks like this gentle upward slope, from the UK’s NHS:

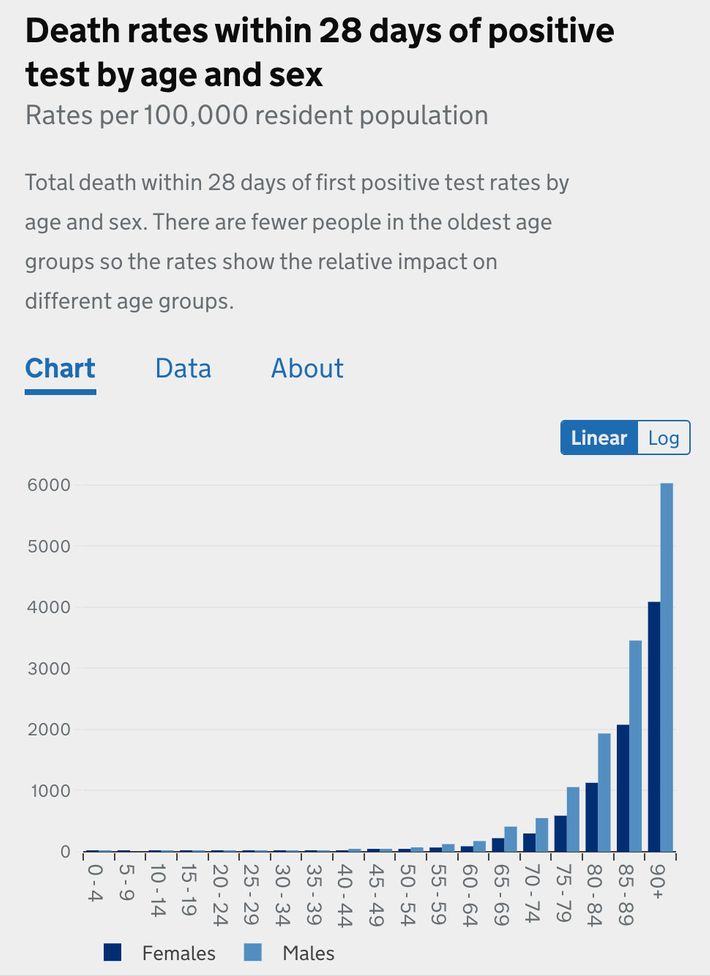

That is a logarithmic chart, which means that the y-axis scales exponentially — a change from one to ten looks to the untrained eye like a change from one to two). That means a huge variation is concealed by presenting mortality risk data in logarithmic form. A chart of the same British information presented linearly (the graphing format you remember from elementary school).

Viewed this way, the deaths from those under the age of 50 are more or less invisible. To scale the graph to make them visible — which would show that the risk slope from children to 50 year olds is about as dramatic as the slope from 50 year olds to 90 year olds — would require zooming in so close that the bars representing elderly outcomes would tower far above the top of your screen.

After 18 months of public-health guidance promoting universal vigilance, I think hardly any American has a clear view of just how dramatic these differentials are. All else being equal, an unvaccinated 66-year-old is about 30 times more likely to die, given a confirmed case, than an unvaccinated 36-year-old, and someone over 85 is over 10,000 times more at risk of dying than a child under 10. And although many infections still go undetected (complicating any attempt at a universal calculation of risk), your chances of dying from a confirmed case roughly double with every five to eight years of age, as countless data across multiple countries demonstrated last year — an effect larger than even the most significant comorbidities. The “exponential growth” of mortality risk by age is, in other words, another aspect of the pandemic we have processed only poorly.

Over the past nine months, vaccination has utterly transformed the shape of the pandemic in the places where it has penetrated the whole population. The effect isn’t just visible in countries like Portugal or Iceland — where the threat appears to be fast receding and which give an encouraging picture of our possible future — but in parts of the United States as well. But for all its transformative, liberating power, vaccination has not broken the basic age skew of the disease or offered anyone an exit ramp from it. Instead, in two profound ways, vaccination has confirmed the age skew: by producing severe breakthrough cases concentrated overwhelmingly in the elderly and by reducing the risk faced by individuals by an astonishing degree that is nevertheless smaller than the still more striking effect of age.

Although vaccines do substantially reduce the risk of infection, too, breakthrough cases are not terribly uncommon, accounting for perhaps as many as one-quarter of all new infections these days, as the CDC estimated in Los Angeles. But they are overwhelmingly mild, and in the rare cases when they do grow severe, they tend to be among the old and very old. According to the CDC, 70 percent of breakthrough cases resulting in hospitalizations and 87 percent of those resulting in death were in patients over 65. The median age of breakthrough deaths in England was 84; in King County, it was 79.

The second confirmation follows from the first and explains why, even given the power of vaccines, there are still some number of severe breakthrough cases and deaths. That 11-fold reduction of risk found in the national CDC study, for instance? Enormous, of course, but it is an average across the observed population as a whole and represents only the equivalent of the difference between an unvaccinated 86-year-old man and a 61-year-old one, all else being equal. According to an analysis of British data by the Financial Times, a vaccinated 80-year-old has about the same mortality risk as an unvaccinated 50-year-old, and an unvaccinated 30-year-old has a lower risk than a vaccinated 45-year-old. Even a 42-fold reduction, as was found in King County, would only be the rough equivalent of the difference between an unvaccinated 85-year-old woman and an unvaccinated 50-year-old — the sort of person who was very worried last year before the arrival of vaccines and who may this year be worrying many of those around them by not getting one.

To be clear: They should get one since doing so reduces disease transmission significantly, thereby limiting the future course of the disease, and because it would reduce their own risk of death from COVID by such a dramatic degree that it doesn’t even make sense to call it a degree. But it’s a sign of just how large the age skew is to begin with that getting vaccinated doesn’t deliver you into an entirely new category of pandemic safety — safer and more protected than anyone who hasn’t gotten vaccinated — but simply pushes you down the slope of mortality risk by the equivalent of a few decades.

On the other end of the age spectrum, the same skew is more comforting. Recent data from the U.K. illustrate the phenomenon neatly: unvaccinated children are safer from COVID-19 death than vaccinated adults of any age:

According to that data, an unvaccinated 10-year-old, who may look like the very picture of COVID vulnerability heading into the school year, faces a lower mortality risk than a vaccinated 25-year-old, whom we might today regard as close to safe as can be. In England, the incidence of hospitalization among unvaccinated kids was lower than that of those vaccinated aged 18 to 29, and in recent weeks, the hospitalization rate among kids ages 5 to 14 has been only about one per 100,000. Over the course of the entire pandemic, which has killed more than 135,000 Brits, just one boy and seven girls between the ages of 5 and 9 have died; between the ages of 10 and 14, nine girls and five boys have died. These are all tragedies — and each means many more years of life lost than with a death among the elderly — but they are nevertheless relatively few in number. As schools reopened on the backslope of the U.K.’s Delta surge, there were about seven times as many British kids under age 5 hospitalized with the respiratory disease RSV as there were with COVID.

Of course, infectiousness matters too; the impact of a disease is a product of both how contagious it is and how severe it is for those who catch it. With COVID, death is not the only outcome of relevance either, and the age skew of COVID hospitalization is less dramatic than that for COVID mortality — with the very elderly, according to CDC data, only 15 times more likely to be hospitalized than those in their 20s. But while some recent studies suggest that hospitalization rates might not be as meaningful as we’ve thought, the effect of vaccines on serious-but-not-lethal infections is, if not sufficient to eliminate the risk, then nevertheless game-changingly large. As for worry about “long COVID,” there are growing indications that the phenomenon, while real, may be considerably less prevalent than many self-reporting surveys have indicated; as the BBC put it recently, long COVID in children is “nowhere near [the] scale feared.”

This is not to say that unvaccinated children face absolutely no risk from COVID, given that many millions of Americans under the age of 18 have gotten sick, and almost 500 have died, over the course of the pandemic. It’s just that the risk those 73 million minors do face is — relative to the risks faced by their parents and grandparents — very, very small. (As I wrote a few months ago, though a better, clearer first line would have been not “The kids are safe,” full stop, but “The kids are safe, relatively speaking”). Precautions are still worthwhile for the unvaccinated young: regular testing, better ventilation in schools, perhaps mask-wearing, too, when community transmission is high. But it is strange and perhaps unfortunate that in the ongoing, unnecessary, often ugly debate about the vaccines — their efficacy, the risk of breakthroughs, and what additional precautions among the vaccinated may be necessary or advisable — almost invariably the discussions describe two groups, the vaccinated and unvaccinated, as though they occupy two uniform and entirely different spheres of risk. Because while the vaccine culture wars are indeed largely binary, and the future of the pandemic in the U.S. largely a matter of how many unvaccinated will get vaccinated, when we discuss individual risk, it simply doesn’t makes sense to talk about vaccinated 15-year-olds and 95-year-olds in the same breath and unvaccinated 15-year-olds and unvaccinated 95-year-olds in a different breath. In fact, it distorts the picture of the pandemic as a whole when we regard risk as neatly divided by vaccination status. That’s because a vaccinated 95-year-old is still probably over a thousand times more at risk of death, all else being equal, than an unvaccinated 15-year-old. Which means we probably shouldn’t be giving those two groups the same advice about masks or social distancing or boosters.

When I asked the CDC about the case fatality ratios implied by its quasi-national study — which suggested, during the observed period, vaccinated seniors were twice as likely to die, given a confirmed case, as unvaccinated people between the ages of 50 and 64 — the lead author suggested that it would be better to consider the incidence rate, which looks at how many people in a given time period suffer a particular adverse event. According to that measure, death among vaccinated seniors was two and a half times more common than death among unvaccinated people ages 18 to 49.

Over the past few months, as we first began hearing reports of breakthrough cases and even breakthrough hospitalizations and deaths, Americans have been treated to a fair amount of columnizing about how, as the vaccination rate grew, we shouldn’t be surprised that the share of serious outcomes among the vaccinated would grow, too — that we should expect it, in fact, and that it would be a sign of vaccine success, not vaccine failure, since it would signal the ongoing penetration of vaccine protection through the population. This is true, in principle, since in a country with 100 percent vaccination, all severe outcomes would be among the vaccinated. But it is also an implicit acknowledgment that some share of the vaccinated population will continue to be at risk. At least for now, plenty of people are still dying, most but not all of them unvaccinated.

And so to believe that the vaccinated elderly are now perfectly safe, as can be tempting to all of us who are desperate for the unvaccinated to get with the program, is to raise an uncomfortable set of questions about the way we have processed risk by universalizing it. If we want to believe, say, a vaccinated 75-year-old is safe, have we now simply normalized a higher level of individual risk than seemed moral to accept as recently as 12 months ago, given that they may not be any less in danger of dying than an unvaccinated 53-year-old? If we are now debating what we can do, in schools especially, to protect unvaccinated children, who are much safer still, should we not be discussing at the same time what measures can be taken, beyond boosters, to protect the vaccinated elderly? Mask wearing offers differential benefits, too: according to the much-applauded study in Bangladesh, cloth masks of the kind typically worn by children offer very little protection, and the strongest effects of surgical masks were observed among the elderly.

These are questions not just for individuals but also for communicators and public-health messaging. Is it now more important to emphasize the protections offered by vaccines in order to encourage further uptake? Or to emphasize the enduring risks faced by the most vulnerable, who might take additional precautions as a result? Because as long as the disease continues to circulate — in part because of frustratingly slow vaccine uptake — there will likely continue to be severe cases and deaths. That’s the brutal logic of the age skew and the vulnerability of the very old it describes. Even universal vaccination among the elderly can’t eliminate those risks, only reduce them. In fact, in several of the recent studies of vaccine efficacy, the effect is notably smaller among the old. (In King County, for instance, where vaccination was calculated to reduce the overall risk of death 42-fold, the effect among seniors was only eightfold.) These studies’ findings obscure confounding variables — that is the nature of epidemiological analysis in real time — but taken together, they suggest that, as long as the disease continues to circulate, even the vaccinated elderly will continue to be vulnerable to some extent.

To what extent? “Post-vax COVID,” as Katherine J. Wu called the “new disease” recently in the Atlantic, is much less lethal overall than the pre-vaxx or unvaxxed variety. But making COVID only as lethal as pneumonia or the flu would still mean, as long as the disease sticks around, probably tens of thousands of American deaths annually. Perhaps a young person can squint at that future and see something that still looks “normal.” But they probably wouldn’t want to tell their grandparents to be blasé about catching pneumonia or the flu, even if they’ve had their annual shot — and might hope that public-health policy focused a bit more on those vulnerabilities rather than simply accepting them.

As we head into the fall, debate over vaccine policy has coalesced around two anchors: the matter of juvenile vaccination and the matter of boosters. On September 22, the FDA authorized booster doses of the Pfizer vaccine for the elderly, high-risk individuals, and those with frequent exposure but not the population as a whole; later in the same week, the CDC director overruled internal advisers to make the same recommendation. To this point, much of the debate around boosters has focused on waning immunity — and it is clear now, in study after study, both that protection does wane and that boosters, already delivered abroad in more than a dozen countries, help significantly. The waning is most visible among the elderly, as many of the studies have shown. But just as important, and much less discussed, is what it would mean to restore that immunity to that group. Because of the age skew, the social impact of elevating protection among the most vulnerable by even a few percentage points would be absolutely enormous. That’s because if vulnerability is hundreds of times higher in one group than another, the impact of that boost is going to be much, much larger too.

That is one reason why a country like the U.K. — enthusiastically considering boosters for the elderly — is at the moment advising against vaccinating even the teenagers already eligible here in the U.S. Vaccines for kids are a reassuring prospect for worried parents and have often been described as an important milestone for school reopening, too (though, to date, less than half of eligible teenagers have been vaccinated, and the rates among younger kids may well turn out to be lower). But in terms of shrinking the country’s overall mortality risk, the enduring fact of the age skew suggests that boosting the immunity of the elderly would be much more consequential. Of course, the effect is not nearly as large as administering new first doses to the elderly in the developing world. Why hasn’t the White House committed to fully funding that effort, again?