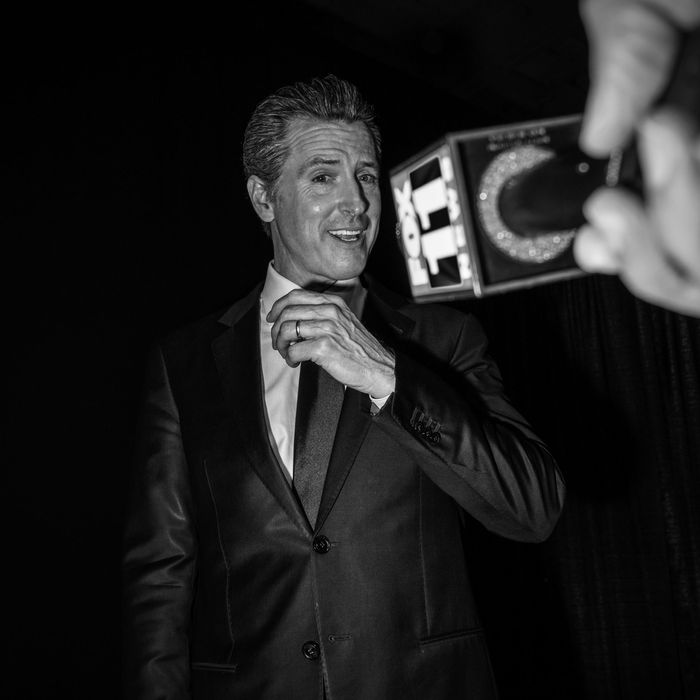

In 2018, Gavin Newsom ascended to the governorship of California with an unprecedented mandate. The former mayor of San Francisco and lieutenant governor of California had been marked for the highest office in the state for decades, thanks to a close association with the most powerful families in California, and he breezed into office with a nearly 3 million vote margin, winning even deep-red Orange County on the way to the biggest landslide for a nonincumbent since the Great Depression. The Biden administration then stocked itself with an impressive corps of California state officials, establishing a California-Washington pipeline that left Newsom positioned as well as anyone in the Democratic Party to make a presidential run at some point in the next decade.

But three years and one pandemic later, Newsom now faces the prospect of being yanked out of office by a special recall election, which will be held on September 14. Permanently mad right-wingers have been trying to recall Newsom since he assumed office in 2019, though their efforts failed to clear the state’s (bizarrely low) bar to actually trigger an election until this year, when they were able to leverage COVID rage to finally squeeze enough signatures out of the state’s electorate and put Newsom on the block. A series of polls in August showed the race narrowing to a dead heat (or worse), though recent polling has put him in a more commanding position.

That Newsom is hated by a certain subset of the California population should be taken as a given. The state may be as reliably blue as any in the union, but its nearly 40 million people are far from a monolith, and California, after all, inflicted both Nixon and Reagan on the rest of the country. Still, seeing Newsom this close to a humiliating defenestration is a real shock. Even if the effort to oust him is being led by far-right paranoiacs, his brush with political death suggests there’s something more to it than the ever-present reactionary forces using the pandemic to take their shot, particularly when you consider that voters under 30 are one of the most reliable pro-recall blocs.

For almost two centuries, California has been built on extractive industry, industrialized agriculture, and, most importantly these days, real estate. But the gold’s all gone now, the money from the tech boom has been mostly hoarded, and the Central Valley heartland is becoming increasingly dystopian, thanks to the megadrought and global-warming–amplified wildfires. Meanwhile, California’s infamous housing crisis is, if you ask experts, really more like three nesting crises: an outrageous 160,000 Californians are unhoused, low-income renters are rapidly being pushed out of cities to the exurbs, and soaring prices limit new ownership to the wealthy.

These issues are not directly Newsom’s fault, even if he comes from California political royalty. He’s just the guy in charge as the slow contraction of what he himself termed the “California Dream” makes itself unavoidably apparent. California is now and always has been the frontier of the American continent, its booming industries built on forever expansion. What happens when the frontier comes to an end?

The wacky and profoundly anti-majoritarian structure of California’s recall system is more central to Newsom’s recall than the substance of the right’s grievances with the governor. While other states have laws on the books that allow for the electorate to trigger a recall election, most of them require petition circulators to obtain the signatures of 25 percent of voters in the most recent gubernatorial election. Thanks to a century-old law intended as a check on the Southern Pacific Railroad’s power, California sets its bar at 12 percent.

This is only one of several oddities about the election. The signature-gathering campaign would have fallen well short if Trump-appointed conservative judge James P. Arguelles hadn’t granted a five-month extension to the campaign, which was being represented by Arguelles’s former partner Bradley Benbrook. Voters have two questions on their ballots, a Yes/No on the question of whether to recall Newsom and then an option to choose one of 46 candidates to serve as governor if Newsom is recalled. If the “Yes” side wins, the huge field will severely dilute the margin of victory. Californians could be left with a new governor who will win with 10 percent as many votes as Newsom earned in 2018.

Because the recall will be held in late summer of an off year (amid a COVID surge that state party officials did not see coming when they planned the election for what they thought would be a post-vaxx, pre-wildfire sweet spot), the primary factor that matters will be turnout. Newsom should win if a sufficient number of people show up, and every registered voter in the state has already been sent a mail-in ballot. While Newsom’s approval rating is relatively strong, he isn’t particularly beloved by Democratic voters. He also made one of the worst gaffes in recent political memory, when he defied his own rules about indoor dining last year to attend a fancy dinner party at the French Laundry. Making matters worse, it was a dinner party thrown in honor of the well-connected lobbyist Jason Kinney, who represents energy-industry interests. It is not possible to generate a more symbolically potent image of an out-of-touch elite than to fête a bagman for the oil industry at the most exclusive restaurant in the state, miles down the road from two acutely destructive wildfires.

A petition has successfully made it to the ballot just once before, and it had nothing to do with robber barons. In 2003, Arnold Schwarzenegger rode a wave of resentment bearing down on then-governor Gray Davis, over his handling of an electricity crisis, to a most unlikely seven years at the helm. Davis’s taxidermied political career serves as a reminder to elected officials that popular frustration can be channeled by sufficiently angry lightning rods and redirected toward them. An important character in the story of the 2003 recall was one such lightning rod, talk-radio host Eric Hogue. Hogue was the most prominent radio host who pushed the recall ballot, eventually getting enough signatures to convince Representative Darrell Issa, last seen unfortunately not retiring, that it was worth throwing a couple million dollars at.

A somewhat similar dynamic is playing out this time around — which brings us to Randy Economy. Like Hogue before him, Economy (yes, that is his real name) is an AM-radio yeller who’s leveraged the loss of his right eye into a persona as a “superhero pirate” who can “spot fake news a mile away.” He lives in the Coachella Valley, and before he started devoting an alleged “17 hours per day” to juicing the recall effort, he spent a few decades flitting back and forth across the line between local journalism and local politics. This led him to the Trump campaign, a job advising Eric Early’s hilariously doomed challenge to Representative Adam Schiff in 2020 (Early lost by 45 points), and, finally, back to Los Angeles–based KABC.

Economy boosted the profile of Orrin Heatlie — the disgraced former Yolo County sheriff’s deputy who started the original recall petition — and helped the recall effort grow into the threat it is today. Economy has since left the RecallGavin2020 campaign, though he’s still actively working against Newsom, and really, his work is done anyway.

Economy crystalizes another important theme of the Newsom recall: the overflowing abundance of weird cranks. Even the people funding the recall effort are, by the standards of dark-money donors, small-time kooks rather than deep-pocketed ideologues. Hell, Newsom’s war chest is more than twice as big as his entire opposition’s. And the lead candidate to replace Newsom, Larry Elder, is fittingly weird.

Elder has been a prominent libertarian AM-radio host since 1993, and he’s used his platform to cast a skeptical eye toward global warming, rail against women’s rights, and let COVID conspiracists take center stage. He’s taken money from the far-right Epoch Times, and even the state’s leading Republicans are like, “Go home, man.” Elder has also been accused of brandishing a gun at an ex-girlfriend during an argument in 2015.

Newsom is, probably smartly, seeking to turn this into a Newsom versus Elder election. And strangely enough, given Newsom’s middling pandemic track record, COVID is one of the main issues he’s staked the race on. Elder, Economy, and Heatlie constantly vent their rage over Newsom’s mask mandates, and pretty much any responsible public-health measures he’s taken to minimize people dying from COVID, but voters tend to overwhelmingly support vaccine mandates and other COVID prevention efforts.

Certainly, Elder or any of the other right-wingers lining up behind him would do a markedly worse job containing the coronavirus, or really meeting any of the challenges the governor of California will be expected to meet. The stakes of this race are as high as the process is odd, and a violent spasm of reaction should not bear anywhere near this much weight. And it wouldn’t, really, if these were normal times, but unfortunately for Newsom, they are not.

Take the fires, for example. Gavin Newsom did not personally doom California to a drier, smokier future. He did not make the choice to mangle fire management by militarizing it rather than ignoring centuries of effective Native mitigation and prescriptive burn strategies, or start the practice of using incarcerated people as an essentially free labor force (though he has not done anything substantial to shift the management paradigm). The eight largest wildfires (and the single deadliest) in California history have incinerated a combined 4 million acres during his governorship, which would have happened under anyone’s watch, because lightning is a famously nonpartisan force.

But Newsom has kicked the can down the road on his promise to end fracking in California, and when asked why he wouldn’t block new construction in the most fire-prone parts of the state, he invoked California’s “pioneering spirit.” That’s a fairly lofty justification to keep doing what the real-estate industry prefers.

Newsom is also a close pal of the tech industry, a force that’s helped California surge to a huge budget surplus. Yet the tech boom has only exacerbated income inequality, and the average Californian has likely experienced the surge less as a direct source of upward mobility and more as an invisible hand that’s made housing unaffordable. There might not be a way to get this rising tide to meaningfully lift some boats instead of swamping them, as the tech industry is so massive that it can buy its way out of scrutiny for a pittance. But there’s a huge lie at the center of the utopian “California Dream” rhetoric that surrounds the tech industry, one that Newsom cannot separate himself from, as long as he’s close to those at the top.

The issue for Newsom is not that California is, as the cynical tax-dodgers who gush about Austin will tell you, a collapsing state being failed further by a gridlocked bureaucracy. The fact is that a state built on the promise of “more, forever” can only expand for so long before being forced to reckon with its contradictions. Newsom may very well survive this shambolic attempt to unseat him, but next time, his enemies won’t be so easy to vanquish.