This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

At some point in the past few years, I looked around at my male friends and realized that they were on drugs.

Not Lexapro or benzodiazepines or Wellbutrin — which everybody was also on — but the kinds of drugs that are taken for age-related complaints. The most common seemed to be Viagra. For a few years in the 2010s, my friend Paul, then barely out of his teens, was buying it over the counter at airport pharmacies in Mexico. He consumed it like an anti-venom for the other drugs he took, to have sex when he was drunk, or high on MDMA. Alex, a TV writer in his early 30s, kept generic Viagra in his wallet for big dates. Without it, he was too nervous to perform with women he’d just met. Lucas took it during group-sex encounters, to fortify himself. Diego, a musician in his late 20s, had started generic Viagra in 2020, when the chemical steroids he used for his workouts unintendedly tanked his testosterone levels, which screwed up his sexual function. He would swallow a pill in the car on the way to his girlfriend’s house, or he’d slip into the bathroom right before they went to bed. As far as he could tell, she never knew.

I was hearing about testosterone therapy, too. Testosterone, to treat a supposed hormone deficiency called “low T,” had risen from a negligible market in 2000 to a multibillion-dollar one in 2020, driven partly by demand from cis males, many of them young. One acquaintance of mine, a trans man who works in health care, wittily described these new practices as “gender for men.” He meant that the act of modifying one’s body chemistry based on sex had previously been associated with women (birth control) and the trans community (estrogen and T).

There was another drug I heard about often: minoxidil, the active ingredient of Rogaine. My friends were not buying Rogaine-branded products, because having a bottle of Rogaine in the shower was not a seductive quality in a young male. Rogaine suggested the kind of guy who, standing in front of the mirror each morning, made a pistol with his finger and shot at his reflection while clicking his tongue. But here was Noah, a contemplative sound engineer in his late 20s, sitting across from me at a bar in East Williamsburg telling me his minoxidil tale. “I was complaining about my hairline, and my iPhone heard me,” he said, “and a couple days later, I’m getting bombarded with these ads.” I studied his hairline. Receding. He was typical of the new minoxidil customer: a man who wouldn’t walk out of a drugstore with a Rogaine bottle but was willing to buy it on an app.

While researching minoxidil, Noah had considered a stronger drug, finasteride, one of the most popular prescriptions in the States for older men. Finasteride raises the level of testosterone in such a way that promotes hair growth. But Noah had read online that finasteride could have sexual side effects. His situation resembled one of those puzzles presented in an undergraduate ethics class, where you find yourself at the wheel of a train that’s on track to run over six people if you do nothing — or you can actively divert the train and kill a single person. Would he rather have hair without erections, or erections without hair? As Noah wrestled with his decision, he ordered a natural hair-loss-prevention shampoo from the company that had served him the minoxidil ad: a San Francisco start-up called Hims. Noah was happy with his purchase. He liked that the packaging was discreet.

Hims was one of a flock of direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies — basically, apps that connect you with doctors who can write prescriptions — that had been founded in the late 2010s to offer minoxidil, generic Viagra, and finasteride to young men. At first glance, the competitors seemed similar, even down to their ads. Hims, which launched in 2017, featured close-up shots of clear-skinned millennials, sometimes embracing; another company, Roman, featured queer couples lounging in the morning-after sheet tangle. One possible exception was a third firm, BlueChew, which sold itself as a rough-and-ready erection-pill merchant with traditional gender roles in mind. In one ad, a husband who cleans the house is rewarded with a BlueChew packet, then starts making out with his wife.

BlueChew had the narrowest business model: It sold sildenafil (as generic Viagra is called) for a low cost and didn’t bother with distractions. Roman pursued a broader strategy, offering so many different medications and supplements — smoking-cessation aids, vitamins — that sildenafil comprised a minority of its revenue. Its average customer was 46 years old.

Hims set out to chase a younger demographic. While Viagra had been a kind of luxury good for older men — the spokesperson was a Republican senator from Kansas — Hims catered to that man’s woke grandson. In the words of one of the brand’s designers, the core customer was “coastal or urban, with a diverse cohort, aware of what’s going on in culture, cares about how they look.” The Hims Man could order sildenafil while waiting in line for Sweetgreen, changing in the Equinox locker room, obtaining knitwear on Mr Porter. In the first three years, annual revenue grew 128 percent, to $130 million, and the number of patient consultations via the app quadrupled to 2 million by the middle of 2020. Most of the customers were men in their 20s or 30s, and they were spending most of their money on sildenafil. Hims claimed there was an undiagnosed epidemic of erectile dysfunction among men under 40, which made them eager to buy these wares. Or perhaps there was another explanation behind the sales figures, a combination of cultural forces that was changing the way men behaved in secret.

In January 2021, Hims went public in a SPAC deal, the first millennial telemedicine company to be listed on a stock exchange. There are now almost half a million Hims customers. In a phrase the CEO uses constantly, Hims wants to become the “front door” of the entire health-care system, the country’s main platform for nonemergency medicine. In addition to sildenafil and finasteride, the brand has expanded to virtual visits with therapists, access to psychiatrists who can prescribe antidepressants, beta-blockers for anxiety, aerosolized lidocaine that is sprayed beneath the penis to delay ejaculation, skin creams, cosmetics, sex toys, a limited form of primary care, and birth-control pills for women (having launched a women’s brand in 2018, the company is now known as Hims & Hers). “We pick up our phone, we click a button, we have full access to the food, the services, the retail — everything we want to buy. It’s a beautiful experience,” the CEO recently told an audience of Wall Street investors. “The only industry where that hasn’t shifted is in health care.” Asked who his core customers were, he said, “The strategy has always been to go after the next generation of health-care consumers: those in their teens, their 20s, their 30s.”

Wall Street has been skeptical so far. Today the company’s stock is down 50 percent from its debut, partly on concerns that it is buying its customers with unsustainably expensive marketing. Hims & Hers is either another scuzzy SPAC in a year that has seen many of them, or it is about to be the Amazon of health care and everybody is asleep and missing it. Whatever the answer, the company is betting that a new male anxiety could be the seedling of an empire, an empire that will spring to life from the little blue pill.

In the winter of 2016, Andrew Dudum, a 29-year-old partner at a start-up incubator called Atomic Labs, was sitting in his office in the idyllic Presidio neighborhood of San Francisco, excitedly following developments in the field of telemedicine law. Dudum grew up in the Bay, raised by Palestinian Christian parents who had fled the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. In high school, he was a music kid, a professional wedding cellist, and an amateur Christian rocker. “It’s a beautiful thing,” he sang in one of his self-released singles, “when the angels fly you to the sky.” As a business-school student at Wharton, he became interested in more earthly forms of ascent, so when he graduated, he went to work at Atomic, which was partially funded by Peter Thiel.

Atomic focused on areas in which the law was shifting, and in 2016, it seemed as though an enormous change was about to occur in the $3.3 trillion health-care market. For as long as there had been an internet, regulators had been cautious of allowing people to get medical care and medications via the web. In the 1990s, states and the federal government had tried to rein in pirate websites selling counterfeit pills, and in 2008, after an 18-year-old man fatally overdosed on Vicodin that had been prescribed to him online, Congress restricted the selling of controlled substances over the internet unless a patient saw the doctor in person first. But as smartphones became ubiquitous, and network speeds fast enough to handle video-conferencing, regulators were under pressure to relax. In 2016 in Texas, home to one of the most restrictive state medical boards in the country, a telemedicine company was pursuing a successful challenge to the rule that said a patient’s initial visit with a doctor had to occur in person. To Dudum and his Atomic Labs colleagues, it was obvious that soon — much sooner than most people realized — the majority of health-care interactions could take place over an app.

The Atomic partners knew something else, too. By one of the luckiest coincidences in American business history, one of the most popular drugs in the country was about to go generic: sildenafil. Another, finasteride, had already come off patent a few years earlier. (U.S. patent law gives a drugmaker 20 years of protection; sildenafil and finasteride had both gone on the market in the 1990s.) Dudum and his colleagues homed in on the concept of a telemedicine business that would begin by offering sildenafil and finasteride to Gen Z and millennials, then gradually expand to other categories.

When Pfizer had run its clinical trials on Viagra in the late 1990s, the scientific literature pointed to an older age of onset for erectile dysfunction. Most young men couldn’t have afforded Viagra even if they needed it: At its peak, Pfizer’s valuable “Vitamin V” cost as much as $60 a pill. Dudum, like many people, was curious about what would happen when the drug went generic and its price fell precipitously. At Atomic, an aspiring founder would sometimes launch an app and website for a nonexistent business and hire an agency to push it using the power of targeted advertising, just to prove that demand existed for its hypothetical product. Dudum joined with two co-founders, Hilary Coles and Joe Spector, and launched an app to test demand for the products among the under-40 demographic they wanted to pursue. Club Room, as the early app was called, started by offering white-label Rogaine, delivered via programmatic advertising into the feeds of young men. “Normally, you serve 100 ads and get zero clicks,” Andy Salamon, a former Atomic partner and early Hims investor, said. “With this, we got 15 clicks. And all of them were actually signing up. It was mind-blowing.” When the team attempted similar experiments with sildenafil, their minds were blown again. Dudum interpreted the demand to mean that erectile dysfunction was widespread among young men but socially stigmatized and therefore underdiagnosed. “These markets that people thought didn’t exist were freaking massive,” he said.

In themselves, however, the pills were just commodity goods. To get big, a company would have to mark the pills up, then cross-sell them with other products and services. It would have to explain to young men why they should feel comfortable taking drugs that had previously been marketed to their middle-aged — even geriatric — fathers and uncles. By the summer of 2017, what had started as an arcane regulatory issue was a contest over selling masculinity.

Dudum wanted to win the contest. That summer, he flew to New York to meet with Anthony Sperduti, co-founder of the branding shop Partners & Spade. Sperduti had helped conjure the personalities of Warby Parker, Harry’s, and Shinola. Dudum had a business plan but nothing else. Sperduti got the sense that Dudum was in a hurry. “These drugs were going generic, so there was going to be a race,” Sperduti said.

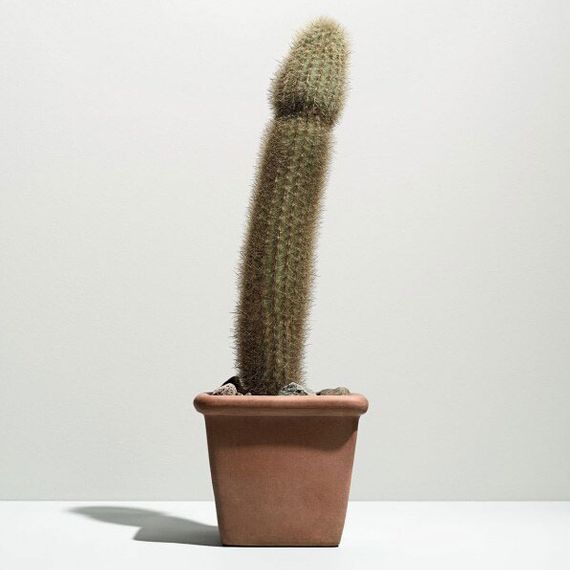

Sperduti and his team invented a persona. For the tone, they settled on something friendly and self-referential, in the vein of the superhero blockbuster Deadpool, which made fun of itself for being a superhero blockbuster. Dudum hired a second agency, Gin Lane, to build the website and make the ads. Gin Lane was associated with the same kinds of millennial proper nouns as Sperduti: Sweetgreen, Warby Parker. A partner there, Dan Kenger, came up with the ads that got Hims the most attention in the early days: pictures of plump cacti with slogans about ED plastered across New York City subway cars. The cactus was shrewd because it held one’s attention while resisting any effort to be taken seriously, the embodiment of both candor and self-awareness. (“You deserve to have an erection when you want one, not just when your penis says it’s allowed,” one tagline read.)

In September, I met Dudum outside his house in San Francisco. The house was big and pink and newly purchased, a clear plastic tarp sighing in the breeze over the front door signaling renovations. The thick-haired 33-year-old who emerged from beneath it wore blue jeans and Jack Purcell–edition Converse, a wooden-bead bracelet on his left wrist. His Arc’teryx windbreaker was swag from Thrive Capital, the VC firm owned by Jared Kushner’s brother, Joshua, an early investor in Hims & Hers.

As we started walking, Dudum unfurled his vision. He said that he pictured a world in which health care became a consumer product that was cheap and convenient: You’d still have insurance for emergencies, but for everything else, you’d use a platform like Hims & Hers. That sounded good at first. But the insurance business relied on a risk-pool model: people paying for the product and not using it. If every healthy young person started avoiding the health-care system in favor of an app, we could wind up with an upstairs-downstairs problem even more acute than the one we currently have. Healthy people with iPhones would get care on their apps while everyone else would rely on traditional hospitals and doctors’ groups that were starved for the easy revenue that they used to make on simple visits. I asked Dudum whether his concept, if fully realized, would upend the health-care system as it existed. “Zero question,” he said.

Dudum’s visions of gender were equally sweeping. Men were averse to getting treatment for things that made them feel vulnerable, he said. Hims was “destigmatizing” those conditions. It was “breaking the masculinity media dynamic.” He said his app would hasten the erasure of gendered expectations. “Masculinity and femininity will be blended. There will be a fluidity between those two.”

Dudum still had a lot to prove. Though there had been a couple of big hires — Lori Jackson, the logistics wizard who had designed Netflix’s mail-order DVD program; Pat Carroll, formerly the chief medical officer of Walgreens — a promising earnings call a few days earlier had done nothing to stop the share-price decline or reassure Wall Street of Hims’ long-term viability. “As a public CEO, most of my job has become talking to the market, to analysts and health-care investors,” Dudum said. “And most of them still don’t get it.” The doubt of others had only made him more evangelistic. “Most people are still coming from a place of defensiveness, of, How do I protect the business and industry that I’ve been monetizing so well? The market is unaware of our opportunity. We have this connectivity with the youth, and 20 years from now, they’re going to be the largest spenders in health care. We’re gonna have the relationship with them. We’ll know what they want and love.”

Male lifestyle brands used to have an obvious purpose: to teach straight men how to entice women. Playboy, the most influential men’s brand of the 20th century, was less a porn magazine than it was a manual for behavior. Even if a man occasionally used his copy as an aid for more solitary pastimes, the magazine’s editorial mix aimed to improve his performance before he got to the bedroom. The articles supplied material for conversation during dates. Advertisements and photo-editorials gave instruction in clothing and posture — how to wear a suit, cross your legs, hold a rocks glass. As the critic Dave Hickey wrote in an iconoclastic essay, Playboy aimed to “civilize” its readers: to lure them into an aspirational world where being a man entailed listening to jazz, caring about art, appreciating wine, being cosmopolitan. Masculinity was about fulfilling a role in the social arena.

Straight-men’s brands since Playboy have mostly hewed to this idea that what unites men as a class is wanting the tools for sexual pursuit — social currency, expensive trappings. You needed the convertible to pick her up. You needed the watch to show her you could afford it. You needed the scent to turn her on. When I was in high school, the tagline for Axe deodorant was “Spray more, get more.”

By the middle of the Great Recession, straight men had plunged from a stable category that advertisers didn’t have to worry about into the center of an identity crisis. The internet had fractured culture into a million pieces, making the idea of “men” as a singular demographic group, with distinct interests you could market to, seem dubious and stale. Nearly every model of aspirational masculinity began to feel passé. Every day, there was another article about whether men were fading into irrelevance. They were less educated than before. There was speculation in academic studies that sperm counts were down by 50 percent since the 1970s for reasons nobody fully understood.

If men’s brands — to say nothing of actual men — were already in a state of confusion, they entered a state of near hysteria in October 2017, when the Times broke the story of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuses. Aggressive male sexuality seemed terminally disgusting, and the details of Weinstein’s own erectile habits were plastered in the Paper of Record, where they seemed sad and pathetic and lurid. Weinstein had paid his assistants to administer alprostadil, an injectable medication for ED, the Times reported in December. His assistants would sometimes “deliver the medication to hotels and elsewhere before his meetings with women.” This sentence was published one month after Hims launched.

Old-school men’s lifestyle brands went crazy in the wake of these stories; even the most banal categories of men’s products were not immune. Gillette, eager to seem of the moment, ran an ad called “The Best Men Can Be,” in which a male narrator patronized the firm’s core customers for 90 seconds in a humorless voice. “We believe in the best in men,” he said. “To say the right thing. To act the right way. Some already are. In ways big and small. But some is not enough. Because the boys watching today will be the men of tomorrow.” Although the ad was conceived and written by a male team at Gillette’s agency, it was the female director, who had joined the project as a hired gun, who was singled out for online harassment. On YouTube, “The Best Men Can Be” remains one of the most disliked videos of all time.

The fact that a company could uncontroversially market Viagra to 25-year-olds while the Me Too movement gathered force is something that requires an explanation, and the explanation begins with the Hims Man. In advertisements, he is never in a social context: He is floated on a background of desaturated pink. There is never a clue as to his profession, never a glimpse of an office, a car, or an apartment. When we see him with a woman, they are practically disembodied — an arm on a shoulder, a closely shaved neck, two eyes gazing into the lens. It’s a post-social landscape where maleness is purely physical. There is no process of seduction. Nobody is in pursuit.

In September, I ordered a pile of Hims products to my home: the anti-wrinkle night cream, the azelaic-acid face cleanser, which arrives in a frosted-plastic jar with a rose-gold top. Inside the box of beta-blockers, which the company once suggested taking to quell nerves before a date, a Hims Man appears on a postcard — late 20s, a redhead, dressed in gym-teacher clothes that I am meant to read as ironic (he’s making pistols with his hands, like a Rogaine Man). On his knee he balances a trophy from the 1950s, the faded surface suggesting age, like it’s Dad’s. The burlesquing with athletic equipment indicates distance from the archetype of the jock. The ironized nostalgia indicates a separation from the previous generation’s norms.

Applying my anti-wrinkle cream before bedtime — the smell is sweet with a base note of coconut, a rebuttal to the muskiness of Old Spice — I try to place the name. Hims. Why is this word familiar? It’s not something I hear in my day-to-day life, but it doesn’t feel like a whole-cloth invention, either. Then I realize: It’s baby talk. “Children make mistakes because they can only use the pronouns they have already learned,” a child-development handbook tells me. A 3-year-old who is trying to distinguish the subjective, objective, and possessive pronouns will sometimes utter a garbled combination. “Jackson brought hims truck today” is the example the handbook provides. It was as though adult masculinity had become so fraught that Hims had decided to dispense with it altogether, casting the Hims Man as a boyish creature earnestly invested in self-improvement. Every time I get an email from Hims, there’s a slogan at the bottom of the message: “Future you thanks you.”

I click SEX at the top of the homepage and am directed to the intake form for sildenafil. A 17-question survey confronts me. The survey includes a modified version of the so-called “Erection Hardness Score,” which was developed during Viagra’s clinical trials. “How often are you having trouble getting hard or staying hard.” “Rate the typical hardness of your erection during masturbation.” “Rate the typical hardness of your spontaneous erections in the middle of the night or the morning.” “Rate the typical hardness of your erection with a sexual partner.” “Do you have any allergies?” My case is assigned to a doctor — he happens to be licensed in Washington, D.C. — who reviews my virtual visit.

Five years ago, this interaction would have occurred in a physician’s office, sometimes at the end of the session in a “hand on the doorknob” moment: “By the way, my friend mentioned …” For the generation below me, it will never not have been this easy. “This is a generation that was spoiled by Amazon,” Dudum had said. Forty-five minutes after submitting the form, I get an email telling me my prescription was approved, and I am charged $36 for six pills. At the bottom of the message: “Future you thanks you.”

Some of my friends were dismissive of the idea that men under 40 were using sildenafil for anything other than fun. “This is about young guys in gamer chairs taking a pill and jerking off,” one friend in his early 30s said. “I’m sure you’ll come up with some empathic bullshit about how being a man is complicated now, but that’s what your article is actually about: jerking off.” The podcast Cumtown, which BlueChew sponsors, made fun of this point of view while endorsing it. The ad spots were self-mocking monologues about using sildenafil to get yourself off. “When I want to get my dick stiffer than a fucking board, when I want to get my dick hard as all fucking hell, I just pop a fucking BlueChew, pal,” went a typical bit. “I popped a couple and went over to my ex-girlfriend’s LinkedIn profile — she’s got me blocked on everything.”

It is difficult to derive meaningful data from scientific studies of erectile dysfunction, in part because they rely mainly on men who sign up to participate and who subjectively self-report their conditions. But in a number of recent papers, separate researchers have reported a possible simultaneous increase in sildenafil use and erectile dysfunction among young men. Dudum said that 20 percent of men in their 20s and 30 percent of men in their 30s experienced ED. Hims & Hers’ head of urology, a physician named Peter Stahl, said he wasn’t sure of the precise number, but “there are lots of younger men that have erectile dysfunction.” Other urologists I interviewed said Dudum’s numbers sounded slightly exaggerated. (Hims played fast and loose even with its own exaggerated statistics. In an Instagram post from 2020, the figure had momentarily jumped to “50% of men in their thirties,” inflating the company’s own addressable market considerably.) But whatever the exact number, the prevalence seemed to be rising. When I asked Jim Hotaling, a urologist and professor of men’s health at the University of Utah, why ED might be more common now than ten years ago, he took a deep breath. “I mean, it’s antidepressants, recreational drugs, pandemics, anxiety, increasing stress, poor sleep, obesity, western diet, on and on and on,” he said. “Good luck with the article.”

Technology and pharmaceuticals were altering every aspect of our psychological and social lives, and chemical interventions were commonplace. Why would sex be exempt from this process of colonization? Most of my friends who used sildenafil weren’t doing it for fun; they were choosing a pharmaceutical solution to a problem of modern life. Diego, for example, used it to have sex with his girlfriend after screwing up his chemistry with steroids, which themselves were a pharmaceutical fix. These were expedient responses to contemporary conditions. (I’ve used pseudonyms and altered identifying details for all the friends in this article.)

For young, single straight men, especially those in their 20s, sex outside relationships often meant isolated encounters with women they didn’t really know. After a few hours of interaction, they were expected to perform in bed. By now, the more evolved guys had realized that sex need not be a story whose climax was their own orgasm, but what hadn’t changed was the notion that men should be able to have sex at the drop of a hat, while women required more factors to align — an emotional connection, a lack of stress, a feeling of security. A man might fear hurting a woman’s feelings if he didn’t instantly respond to her physically, and there was no cultural script to ease that tension. In the porn videos that taught a man how to have sex, he rarely saw an actor lose an erection — or get one, for that matter. He might be on antidepressants that helped his mood but had side effects that embarrassed him. A pandemic had shredded his sense of social fluency. He’d be sheepish when asking his doctor for help — assuming he could afford health insurance, which he probably couldn’t. In this environment, it might be impossible to distinguish a physical problem from a psychological one, an organic disorder from an inevitable response to the weather in the sexual atmosphere.

In September in San Francisco, Hilary Coles, the co-founder who is now a senior vice-president, ran a meeting with her design team to discuss the marketing of a new product: talk therapy. Unlike primary care — another area that Hims & Hers was testing — therapy offered the possibility of a weekly recurring revenue stream from hundreds of thousands of subscribers.

Recurring revenue was important because, underneath the high subscriber numbers and the visible brand personality, Hims & Hers was losing a lot of money. Fifty million dollars had gone out the window just last quarter. Like many start-ups, H&H burned much of its cash on social-media advertising. According to its financial filings, it spends $376 to acquire each new customer, which means it has to make an average of $376 off each customer in order to be profitable. There were two ways out. It could get a lot more customers and hope those customers stuck around, or it could start making a lot more money per customer — turning each sildenafil user into a therapy patient, for example. These were the stakes of the meeting Coles was holding with her team.

Dan Kenger, the cactus-ad visionary who had left Gin Lane and become Hims & Hers’ chief designer, presented some possible ads for Coles’s approval. In the first picture, an athletic middle-aged white man with a salt-and-pepper beard was dressed in a black suit jacket, looking over his left shoulder and holding a football. “Get your mind right,” the tagline read. The next image was a younger biracial guy in a tank top wearing Bluetooth headphones. His eyes were closed in the coiled-spring focus that is familiar from the black-and-white portraiture in Nike ads. The tagline read, “Your mind takes no days off.” A third image showed a rugby-captain-looking white guy with a menacing squint, who seemed as though he was about to leap out of the frame and tackle me for not confronting my commitment issues. Tagline: “Get your head in the game.” Shelby Neal, Hims & Hers’ head copywriter, had ideas for ad copy. “Just like a guy will master a new skill on the court,” she said, “they’re putting this effort into mental health. That might sound like an overwhelming task, but with Hims, we make it easy.” She pitched a tag: “As you’re calling the shots, we’re here to help you make them. Hims is here to help you get your head in the game.”

With enough of an advertising budget, and a constantly expanding network of physicians and therapists, Hims could make itself into an essential part of life for hundreds of thousands of people, many of whom would never otherwise get treatment. They could enjoy the ease of access, the nice design, the quick responses to their messages from doctors who were thousands of miles away. What they couldn’t do was leave the profit-making ecosystem: Health care was becoming a lifestyle product, and the core feature of the lifestyle was continuing to pay for treatment.

Neal finished her pitch, and Coles considered for a moment in quiet. “It’s missing a little humor,” she said finally. “ ‘Get your mind right’ — what does that mean? Does that make me want to go hit up the Hims mental-health page? Remember that insight we were playing with a while back? ‘How far would you go if you could stop outrunning your problems?’ ”

A few days later, I went home to Los Angeles, where the rose-gold top of the azelaic-acid cream was glinting on the shelf in my bathroom. There was anti-wrinkle cream beside the sink. Sildenafil was in the mail, pills I wasn’t sure whether to throw away or keep. Categories were changing, and the social performance of maleness allowed more openness. You could be fluid; you could be vulnerable. As long as you were also hard as a rock.