Yesterday, Omicron panic swept across the internet, and through the city, as informed Americans started belatedly reckoning with what terms and phrases like “doubling every two days,” “Rt of six,” and “two to three times as infectious as Delta” really meant: a coming tsunami of cases, quite likely bigger than anything we’ve seen before in the pandemic. The U.K. set a new record high for cases yesterday, after setting one the day before, and there are warnings of a million new infections per day by this weekend — the equivalent of 5 million in the U.S.

What that tsunami means in terms of ultimate outcomes is still not clear, but on two critical questions — the likely duration of an Omicron wave, and the relative severity of disease caused by the new variant — there has been some news recently, too. And it is — all things considered, given the near-inevitable scale of the coming case surge — encouraging.

The first piece of good news is that this wave might be shorter lived than those of other variants. Every country is different, of course, with different population structures and different levels of immunity, both “natural” and from vaccination. But in South Africa, it appears that, while test positivity is still growing throughout the country, in the Omicron epicenter of Gauteng the wave may be peaking already, with cases and hospital admissions both taking a visible turn, barely three weeks since the variant was first publicly announced and just five weeks since the first likely case. Gauteng is not all of South Africa, of course, but a fast local peak still suggests the possibility of a very fast first wave. If the pattern holds and is replicated in the U.S., it could mean an American Omicron peak of cases sometime before the end of January.

But while this is much better than the alternative — a longer South African wave, with many more cases, reaching ultimately a much larger share of the population — it is also not necessarily a safe bet to be replicated elsewhere. In South Africa, it appears Omicron may now be peaking with only roughly as many recorded cases as were recorded at the peak of the country’s Delta wave; in the U.K., they have already broken their all-time record, and are heading way up from there. Perhaps this means that South Africa is vastly under-testing, and the true infection count is, in fact much higher — though this would be encouraging, too, since it suggests that an even larger proportion of total infections are too mild to register. But it could also mean that — perhaps because of population structure, perhaps because of differences in acquired immunity — we simply can’t extrapolate the South African experience to other countries. Two years into the pandemic, there is still an awful lot we don’t truly understand about the dynamics of disease spread and precisely why waves taper, peak, and decline, often well before reaching most vulnerable people. Time will tell, since if the U.K. is following the South African path we’d probably see that curve bending within a week or so.

The second piece of good news is that as the wave progresses in South Africa, the cases continue to appear mild. This data is still early; typically, infections take several weeks to complete their clinical course, and probably we won’t have a clear picture of the relative severity of Omicron in South Africa for another week or two, either. (As science journalist Kai Kupferschmidt wrote recently, “This pandemic has been all about communicating uncertainty and it doesn’t get more uncertain than early data on new variants.”) On top of that, the picture will reflect conditions in South Africa as much as the “inherent” severity of the new variant, which means that, while illuminating, that forthcoming data will not be definitive, at least as concerns the future course of the Omicron elsewhere in the world. As William Hanage and Roby Bhattacharyya have argued, the early data might just reflect local acquired immunity, which offers significant but incomplete protection against severe disease, rather than innate properties of the variant itself. (This would make the relative protection of a given population a much more significant factor in the ultimate course of the wave than even how severe Omicron itself is.) But while excess deaths are beginning to grow in Gauteng, indeed at the same rate as earlier waves, there are reasons to believe that the ultimate toll will be smaller than with Delta and earlier variants — namely that, unlike in those previous waves, deaths in this wave are increasing at a much slower rate than cases are. At the moment, as John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times has tabulated, cases in Gauteng are at 95 percent of their Delta peak, with deaths at only 10 percent of that peak; in the U.K., the proportion is the same. That is not to say that we should expect, at the end of the wave, proportionally only one-tenth as many deaths as were observed in the earlier waves — there is a lag, often several weeks long, between case peaks and death peaks. But it is nevertheless an encouraging sign that the early indications that Omicron might produce, overall, more mild outcomes are still holding.

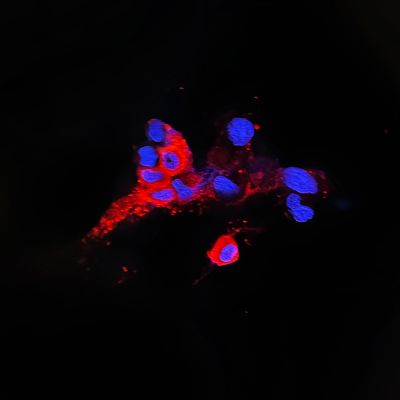

And the third piece of good news is that we now have a possible biological explanation for reduced severity, which gives the observed preliminary data another layer of plausibility. That comes from research by the University of Hong Kong, which finds that the new variant is much more efficient in reproducing in the upper respiratory tract, where you can cough and sneeze it out onto others, and much less efficient in the lungs, where it will be most dangerous to the infected host. A few weeks ago, in the very earliest days observing Omicron, the epidemiologist Francois Balloux called this the “highly optimistic scenario” which, if it came to pass, would mean the world had gotten “really lucky.” (He also suggested it could be a sign that the virus was, in fact, evolving in response to vaccines — not in the way anti-vaxxers believe, by making it more virulent, but the opposite.)

There are massive caveats here, including that it is still very early; that we are still trailing the lag between cases and severity; that we don’t know that much more about this variant than we did a few days ago; and that, especially in a population lacking in immune protection, a massively transmissible variant can be devastating even without being especially virulent. (Indeed, this is how COVID-19 has killed all along, not by being apocalyptically severe, but by spreading so quickly through an immunologically naïve population.) But the biggest note of caution I would offer about the likely American experience of Omicron is this: When the U.K. had its big Delta surge, over the summer, its level of vaccination (particularly among the elderly) meant that, compared with the number of cases, the level deaths fell ten-fold from the ratios of the winter surge; when Delta hit the U.S., our notably lower level of vaccination (particularly among our elderly) meant that, compared with the number of cases, our level of death did not fall at all.

The U.S. is not much more vaccinated now than it was then — indeed, our Delta wave is still ongoing, though down from its peak in September and October. According to CDC data, there are 130 million Americans who don’t yet qualify as “fully vaccinated,” and 280 million who have not yet received a booster. Among seniors, there are about 10 million who aren’t yet “fully vaccinated,” and 20 million who haven’t yet received a booster. We know those numbers are unreliable and overstate the degree of protection; and we know that waning immunity means more Americans are probably losing protection right now than gaining it through new vaccinations or boosters. And while a significant share of unvaccinated Americans have been exposed to the disease already, that share is far from 100 percent, and we have reason to believe that previous exposure is less protective against Omicron than it has been against earlier variants. Which is all to say that, whatever good news there is already emerging from South Africa and the U.K. and whatever good news may come over the next several weeks, a tsunami of cases may well produce considerably more brutal outcomes here.

Sharing the Hong Study, the virologist Muge Cevik cautioned … caution. “The only thing I am sure of is that Omicron will spread so quickly through the population, making it likely impossible to contain even with the most stringent measures & giving us very little time over the next few weeks,” she wrote. “Get your vaccines & boosters!”

More on omicron

- What to Know About the New COVID Booster Shots

- The Dismantling of Hong Kong

- What We Know About All the Omicron Subvariants, Including BA.2.12.1