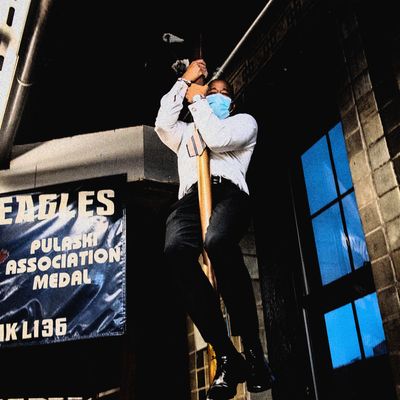

“I’m going to put in long hours — no one in this city is going to outwork me,” Eric Adams said on day one, and he went on to rack up at least 47 public appearances in his first ten days as mayor — traveling to work on a Citi Bike and the subway, shoveling snow off the steps of his Brooklyn brownstone, sliding down the pole at a firehouse, making guest appearances on national news programs, and solemnly attending a vigil in the Bronx following a horrific fire that claimed 17 lives.

“It’s not about showmanship — it’s about showing up,” he said in his first address to the city. Like Mayor Ed Koch, who took the reins at City Hall four decades ago in the shadow of a fiscal crisis that required massive layoffs and belt-tightening, Adams is making hard choices — his budget chief has already ordered agencies to outline plans to reduce spending by at least 3 percent before the end of the month — but he is also trying to cheer up a weary city in need of a morale boost as we head into the third year of the pandemic.

“When a mayor has swagger, the city has swagger,” Adams said in unscripted remarks at a school in the Bronx, flashing a big, bright smile. “We’ve allowed people to beat us down so much that all we did was wallow in COVID,” he added. “We no longer believed this is a city of swagger. This is a city of resiliency.”

New Yorkers should expect to hear more pep talks from City Hall as our faltering local economy struggles to get up on its feet. Right now, the city’s 9 percent unemployment rate is nearly twice the national average, and we still have 350,000 fewer jobs than before the pandemic and aren’t expected to fill them until 2025.

Adams, pleading with city employers to end remote work and reopen offices, raised eyebrows at a press conference by making a tone-deaf reference to “my low-skill workers, my cooks, my dishwashers, my messengers, my shoeshine people, those who work at Dunkin’ Donuts — they don’t have the academic skills to sit in a corner office.”

Critics including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez quickly pointed out that the mayor should be more concerned about the low wages of essential workers than offering pejorative comments about their perceived educational backgrounds and skill levels. Adams later took to Twitter to point out that he had worked as both a cook and a dishwasher himself.

The mini-gaffe is likely to be remembered by the chattering classes but surely did nothing to shake Adams’s connection to the working-class families that make up his political base. A more serious set of challenges has emerged in the form of harsh headlines and scolding editorials — which he knew were coming — about ethics issues surrounding his personnel picks.

“It’s a bit dispiriting to see the new mayor really want to launch his war on crime this way,” wrote the New York Post editorial board, slamming Adams for trying to steer his younger brother, Bernard Adams, into a top NYPD job and for picking Philip Banks — a friend, business associate, and travel companion of several men convicted in a corruption scandal — as deputy mayor for public safety.

The Daily News also had tough words. “The mayor skipped important steps in the process. He should change course,” the editorial board said of the plan to hire Bernard Adams. As for Banks, the paper warned, “By bringing into his inner circle a man who played a sizable role in one of the most sordid chapters of de Blasio’s term, Eric Adams is taking a risk.”

Adams has indirectly responded to the criticism. After first announcing his brother would be a deputy NYPD commissioner, Adams downscaled his proposed responsibilities to running the mayor’s personal security detail, and he agreed to abide by whatever guidance comes from the city’s Conflicts of Interest Board. “I need someone that I trust around me during these times for my security, and I trust my brother deeply,” he told CNN’s Jake Tapper.

And while Adams continues to defend Banks — the brother of his schools chancellor, David Banks — the mayor took the unusual step of allowing him to announce his own appointment in an op-ed article, a sharp contrast to the lengthy televised press conferences at which his first five deputy mayors were introduced.

Adams is clearly betting that complaints about his personnel choices will fade from the headlines if his team can deliver on his core campaign promise: making New Yorkers feel our streets and subways are safer and more orderly.

It’s been done before. In the 1990s, one reason Rudy Giuliani became a two-term Republican mayor in our overwhelmingly Democratic city is he strongly accelerated a drop in street crime that began under his predecessor, David Dinkins, and took sole political credit for the subsequent dramatic rise in safety, picking up crossover Democratic voters in even the most liberal neighborhoods who were at wit’s end over crime and disorder.

Famously, when Giuliani’s flashy, innovative NYPD commissioner, Bill Bratton — who’d conceived and led the implementation of the department’s data-driven CompStat management system — showed up on the cover of Time magazine, Giuliani fired him within a matter of weeks, replacing him with a fire commissioner, Howard Safir, who kept a low profile and took care to never upstage his boss.

Adams, in the Giuliani mold, is clearly planning to run the NYPD from City Hall and to take 100 percent of the credit if crime gets driven down.

Consider his appointment of Keechant Sewell as police commissioner. A rising star in law enforcement, Sewell had never worked in New York City government, and her experience managing the 350-member detectives bureau of the Nassau County Police is dwarfed by the NYPD’s 50,000 uniformed and civilian personnel. It will take time for Sewell to master the vast scope, culture, and internal politics of the NYPD in contrast with the men she will report to, Banks and Adams, who are veterans with longstanding allies and connections throughout the department.

Adams, Banks, and Sewell have yet to unveil any major initiatives or fundamental changes to NYPD strategy. If they are open to new ideas, a couple are ripe for the taking.

Naveed Jamali, a technology and national-security expert, has been preaching the merits of having the NYPD share its 911 dispatch data. “We’ve become a society of data. And the NYPD is no slouch in the amount of data that it produces,” he told me recently.

Jamali said a close analysis of 911 calls — most of which never result in an arrest or evidence of a crime — would likely generate valuable information about where problems are likely to crop up in the future. Repeated police visits to a particular address could serve as a warning system that gun violence, domestic violence, illegal drug sales, or a mental-health crisis is likely to occur.

“That is what we in the intelligence world would call ‘indications warning.’ You’re indicating there’s a trend here that’s showing that this is leading to some crisis,” he said. “Whether it’s gun violence, whether it’s any of this stuff, the idea is to try to disrupt it before it reaches that critical phase. And what my hope would be is that the NYPD, which siloes this data, would be potentially willing to open it up to other agencies — not to use it themselves but instead open it to other agencies that can help make their job serving the city better.”

A similar logic is driving a group of advocates who filed a class-action lawsuit against the city in the final days of the de Blasio administration. The group argues that the NYPD has violated the state and federal Constitutions and the Americans With Disabilities Act by allowing police officers who lack medical training to make snap, on-the-street diagnoses of who is an “emotionally disturbed person” and subject them to arrest, imprisonment, or deadly force.

The coalition behind the lawsuit is calling on New York to get cops out of the business of responding to so-called EDP cases and instead to dispatch trained, unarmed medical specialists and peer-group members, modeled on a program in Oregon called Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets that has operated successfully for nearly 30 years. In 2019, the program responded to 24,000 crisis cases with police backup called in only 150 instances.

“This isn’t really about the police and how the police can do things better — it’s about getting them out of the picture entirely,” said Ruth Lowenkron, director of the disability-justice program at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest. “It’s not a criminal legal matter; it’s a health matter. And we want to therefore send in a health response.”

Lowenkron hopes the coalition suing the city can meet with Adams, who talks frequently about breaking down barriers between city agencies. “I have been very vocal with people on the transition team to let them know what I’m thinking. And I’m cautiously optimistic that my message is getting through,” she said.

That question — Is my message getting through? — is one that countless advocates, business owners, parents, and homeowners are asking. Adams has talked a strong game up until now, but will he make good on it?

“I think his first week in office has been quite extraordinary,” said Betsy Gotbaum, the former two-term public advocate who now runs the good-government organization Citizens Union. “We just had a board meeting, and of course everybody was talking about the optics of his appointing his brother and his friends,” she told me. “But they also feel there’s somebody in charge in the city. He’s having a good time — but boy, was he on top of things when things didn’t go so well. On one level, it was a terrible week for him, but he handled it really well.”

More on eric adams

- The Woman Who Ate Eric Adams for Breakfast

- On Patrol With the New York City Rat Czar

- Earthquake and Aftershock Shake New York City: Live Updates