For three weeks in November, I became addicted to the livestream video from a commercial courtroom in lower Manhattan, waking at 5:30 a.m. in my apartment in Los Angeles so I could be stationed at my laptop by 9 a.m. ET. My addiction wasn’t easily explained, because the dispute in this trial seemed extremely boring. Actually, it seemed like the most boring thing I could imagine: A rich guy was suing his former company for money that would make him even richer. Sometimes, when I clocked in at 5:50 a.m., I felt that I was subconsciously punishing myself. And that was in the rare moments when I could even see what was happening: Most of the time, the livestream was configured so that the speaker’s head appeared in a blurry corner of an otherwise all-black screen. Every so often, the feed would totally crash, and the trial would pause while the judge called the tech-support person to come downstairs and help him.

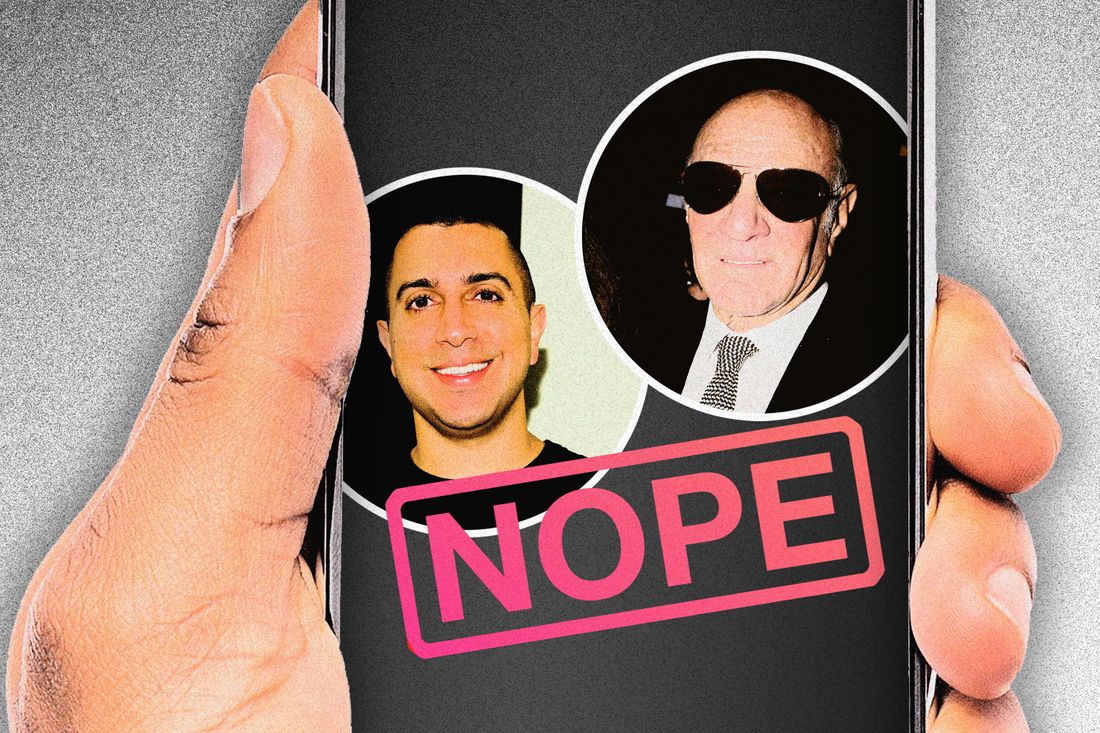

What kept me watching was that, beneath the arguments over money, another story was playing out. That story was the emotional drama between the parties: Sean Rad, the impulsive 35-year-old founder of Tinder, and Barry Diller, the 79-year-old yacht-riding media mogul. Rad had spent three years pursuing Diller through the court system, seeking money that Diller’s firms had allegedly stolen from him. The single-mindedness of Rad’s hunt and his refusal to take a settlement — most commercial cases are resolved without a jury entering the picture — had the unrelenting quality of a revenge quest, in which the protagonist doesn’t give up until he confronts the antagonist and kills him (or is killed by him). The only difference was that instead of shooting and dismemberment, the action took the form of witness testimony and courtroom motions by lawyers from white-shoe firms.

In 2018, Rad had filed a 55-page complaint against Diller’s media conglomerate, IAC, which at that time owned Tinder. According to the complaint, IAC had scammed Rad personally out of more than $1 billion. The mechanics of the alleged scheme were dark and shadowy, involving a monthslong financial conspiracy, doctored financial projections, secret meetings, and unscrupulous investment bankers. As I read through the case file, though, the alleged tactics began to intrigue me less than the broader picture that the lawsuit had inadvertently revealed. There were 2,500 documents in evidence. They introduced me to a story I’d never known about — the contest for ownership of the intellectual property that had changed the way a generation had sex and fell in love.

The tone of the dispute, revealed in hundreds of formerly private texts and emails, was vicious and profane, like a bad divorce. Rad had written, “Fuck him. We’re at war. We will destroy him,” about the CEO who had replaced him at Tinder. In a separate filing, that CEO was quoted as calling Rad a “fucking nut.” There were claims that a sexual-harassment incident had been disclosed against the will of the victim in order to damage the career of the alleged harasser.

By the time pretrial got going in October, both sides had availed themselves of experienced PR agents. Diller’s company chose Justine Sacco, famous for being the first person to be globally canceled: In 2013, she had tweeted before departing on a flight for South Africa, “Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” (When she landed, she learned the tweet had gone viral.) Rad’s side was using a boutique firm run by a young woman named Ashley Rust, whose website advertises assistance with “a broad spectrum of online issues and challenges.”

The opening day of arguments in Rad v. IAC arrived in November. When Sean Rad walked into the courtroom, he seemed at first to be bland and unassuming, his crew cut and understated blazer suggesting an almost self-conscious distance from the hotheaded younger man who had threatened to start a war to “destroy” a business rival. When he sat down on the witness stand, though, the traces of that other person were visible. Rad bristled with the barely contained energy of a person who has over-rehearsed for a confrontation.

“Are you nervous?” his lawyer, Orin Snyder, asked him.

“Yes.”

“Why are you nervous?”

“I waited a long time to be here,” Rad said. “It’s been a long road.”

In February 2012, when Rad was 25, he took a job at a start-up incubator in Los Angeles at a salary of $160,000 a year. Rad was a USC dropout from a wealthy Iranian American family in the Valley with nothing much on his résumé except for a few stalled start-ups. He described himself as awkward and shy, especially when it came to approaching women.

That spring, the incubator held a hackathon — a contest to come up with the best idea for a new business. Because most people’s ideas for new businesses are terrible. But Rad’s team turned over an ace: a dating app that would connect users only if they had already expressed mutual interest. Rad thought the business should be called “Tender,” as in the emotion, but his co-founder Whitney Wolfe thought it sounded too mushy and suggested changing the e to an i. About a year later, Rad and his co-founders filed U.S. patent application No. 9,733,811B2, for a “Matching Process System and Method” that enabled communication between users who made a rightward “swipe gesture” on each other’s profiles. In the industry, the technology became known as “double opt-in.”

According to Rad’s agreement with the incubator, called Hatch Labs, any ideas he conceived as an employee became “the exclusive property” of Hatch. Rad was Tinder’s CEO but not its legal owner. The Tinder name, double opt-in, the brand — none of it belonged to him. Hatch Labs, for its part, was partly owned by the Match Group — the dating-site roll-up that included Match.com, OKCupid, and Plenty of Fish. And Match was owned by IAC, meaning Barry Diller.

Rad knew just a little about Diller: He believed that the older man was “a very powerful media mogul” in New York. If anything, this understated Diller’s position. Formerly the chairman and CEO of both Paramount Pictures and 20th Century Fox, Diller is the kind of vintage legacy-media mogul whose fingerprints seem to be everywhere. He had green-lit The Simpsons; he ran Expedia.com; he had basically launched Vimeo. Among his former mentees — called “Killer Dillers” in the business press — he counts the CEOs of both Uber and Disney and a co-founder of DreamWorks. In 2001, he married the fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg. He is larger than life.

As Tinder grew, its success came to Diller’s attention. “Talking today to one of the deck crew on my boat,” he emailed Rad in March 2014. “They said that Tinder has been a social godsend in more ways than browsing. The boat travels a great deal, and is now in the Caribbean, lots of islands to and fro. They’re always seeking information on good restaurants, activities, etc. and once they’ve got some matches, they then start a dialogue.” He continued, “You probably have endless anecdotes, but for me, this one confirmed in a real way that the platform can be used in many ways other than ‘dating.’”

Rad responded politely, but privately he was unhappy about the relationship between himself, the Match Group, and IAC. If he had been like any number of tech founders, a person familiar with the lawsuit told me, he would have raised some VC and owned the company; he would have been Mark Zuckerberg. Instead, he was making money for other people. When Rad met Diller in person for the first time, at the Beverly Hills Hotel in Los Angeles in 2014, he said that he hoped to redo his deal.

That summer, IAC agreed to give Rad and the Tinder co-founders a new compensation agreement. Beginning in May 2017, Rad would receive a package of stock options worth 12 percent of the value of Tinder. Plain and simple on one level, the deal actually contained a land mine. The land mine was, how do you determine the value of Tinder?

In the public markets, a company’s market capitalization becomes a kind of shorthand for its value. Apple is “a $3 trillion company”; Pfizer is “a $300 billion company.” Whether this metric means anything is debatable — particularly as markets seem to do nothing but go up, even in the face of civilizational breakdown — but at a minimum, there’s an objective, external way for two people to look at the same business and say what it’s worth. Tinder had no market capitalization, because it was not a public company; it was a subsidiary of a public company, the Match Group.

The 2014 agreement landed on a convoluted solution. When it came time to value the business, Rad and Tinder management would each have their own investment banker, who would comb through the financial data and eventually agree on the number. Because the financial data was all on Tinder’s computers, the process depended on Tinder management disclosing all the data honestly to the investment banks. In 2014, that probably didn’t seem like a big deal: Rad might have had every reason to think that he would be running Tinder when the valuation process occurred — that he would be in charge of providing the data to the banks.

In June 2014, just as Rad signed the options deal, the Tinder co-founder Whitney Wolfe filed a lawsuit against Tinder and Match alleging “atrocious sexual harassment and sex discrimination.” Wolfe had been dating Justin Mateen, another co-founder, and when the relationship ended, Mateen became aggressive, calling Wolfe “a gold digger” and a “disease.” He called her a “whore” during a company party. Feeling threatened when a blogger wanted to write a feature on Wolfe, Mateen said that he would “fuck” the blogger’s wife, and that the blogger would “be a handyman for my backyard and will be on a leash.” Mateen elaborated, “I will shit on him in life.”

According to Wolfe, when she raised Mateen’s behavior with Rad, he’d declined to discipline Mateen. Instead, he’d pressured Wolfe into resigning; if she didn’t, according to Wolfe, Rad threatened that “things were going to get ugly.” When the complaint went public, along with screenshots of the relevant texts, it stained Tinder’s reputation. The Daily News headline was “Female Tinder Co-founder Was Pushed Out, Called ‘Slut,’ ‘Whore’ in Front of CEO.” Gawker published “Every Fucked-up Text From the Tinder Sexual Harassment Lawsuit.”

Rad made things worse whenever he got in front of an interviewer. The year after the Wolfe lawsuit, he described his romantic taste to the Evening Standard:

Attraction is nuanced. I’ve been attracted to women who my friends might think are ugly. I don’t care if someone is a model. Really. It sounds clichéd and almost totally unbelievable for a guy to say this, but it’s true. I need an intellectual challenge. Apparently there’s a term for someone who gets turned on by intellectual stuff. You know, just talking. What’s the word? I want to say “sodomy”?

The article included made-up financial data, exaggerating the number of Tinder’s active users by several million. The fake numbers weren’t attributed to Rad, but he didn’t contradict them, which looked bad. In response, the Match Group filed a document with the SEC that hung Rad out to dry. “Mr. Rad is not a director or executive officer of the Company and was not authorized to make statements on behalf of the Company for purposes of the article,” the filing read.

From his offices at IAC, Diller followed the unwelcome twists at one of his fastest-growing subsidiaries. Rad seemed like a jockey who was riding a prize horse all wrong: Tinder revenue was growing at triple-digit percentages every year, yet every day seemed to bring a fresh stumble. Diller decided that Rad would need to be replaced.

Holding companies like IAC will frequently shuffle their trusted executives from one subsidiary to another as a means to exert control over the empire. The man Diller had in mind for Tinder, Greg Blatt, had been CEO of the Match Group for several years. Whereas Rad was a young and inexperienced dropout with a great idea, Blatt, then 48, was a lifetime corporation man with a law degree from Columbia and a ferocious temper. Before working for Diller, he’d served as head lawyer for Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia during Stewart’s insider-trading scandal. Blatt did not ask to be assigned to Tinder; he was happy where he was. But Diller flattered him, telling him that true leaders go where the trouble is. “As hard as it may be,” Diller wrote to Blatt, “go out there and stay until the problem is solved one way or another.”

Blatt got to Los Angeles in December 2016. “As I sit here in my LA office, 8am on Saturday morning after a string of 13-hour days since New Year’s,” he wrote to Diller a few weeks later, “I can tell you this place is so fucked up that it’s unbelievable. To call it amateur hour would be an indefensible insult to amateurs.” According to a Tinder employee who worked at headquarters at the time, Blatt thought Tinder had gotten fat on its initial success with no processes in place to replicate it. “Tinder had grown like a weed by chasing cool kids,” a former employee told me, “but they actually didn’t know what drove their growth.” Blatt wanted measurable results, long-term plans, accurate financial forecasts.

He clashed with Tinder’s culture. At one meeting attended by multiple Tinder employees, Blatt seemed to confuse the acronym IRL with the country code for Ireland. This seemed metaphoric: The head of the app that converted online interactions into physical dates was unfamiliar with the phrase “in real life.” (A spokesperson for Blatt dismissed this anecdote as “absolutely ridiculous.”) His effort to modify the lavish meal program — which Blatt thought might be a tax liability — led some Tinder employees to fear that he would terminate free food altogether. “I said, ‘You can’t do that,’” one former Tinder director told me. “‘There will be a revolt.’”

As CEO of Tinder, Blatt would be in charge of the valuation that was mandated by the 2014 contracts — the process that would determine how much Sean Rad’s options would be worth. But Blatt had another role, too: He remained the CEO of the Match Group, Tinder’s parent. Rad believed that this constituted a conflict of interest: Because Match was the counterparty to Rad’s stock options, the more that Tinder was worth, the more Match would have to pay. Rad suspected that Blatt would favor the interests of Match and IAC over the interests of the Tinder founders.

Blatt had been sent to L.A. largely to deal with the fallout of an enormous sexual-harassment scandal, which made his behavior at the 2016 Tinder Christmas party darkly ironic. That night, Blatt got drunk and flirted with Rosette Pambakian, the VP of marketing and communications. They wound up in a hotel room along with two other employees. In a legal deposition several years later, Pambakian said that Blatt then “climbed on top” of her on the bed and started “kissing my arms, my shoulder, my neck.” Blatt said only that they consensually “engaged in some snuggling and nuzzling.”

Pambakian worried that it would ruin her life to report the incident: She wanted her accomplishments at Tinder to define her, not Greg Blatt’s behavior. To protect herself from the media spectacle, she decided not to raise the party with Tinder human resources. It seemed as though it would stay secret.

That spring, the valuation process started. At first, Blatt and Rad attempted to bypass the complicated valuation process and agree on a number between them. These discussions broke down when Rad’s figure dwarfed Blatt’s. Rad hired an investment banker named Storm Duncan, who came from the respected firm Jefferies. Duncan and Rad concluded that Blatt would try to tank the process intentionally, and they resolved to fight for a high valuation. While Duncan worked the official channels, Rad was on a group chat with an anti-Blatt faction of Tinder vice-presidents, who strategized how to game their meetings with the banks (one idea was to refer to the financial model as “this model” instead of “the model” to “subconsciously open their mind up”).

Rad believed that Tinder was comparable to an early-stage Uber or Facebook and thought the valuation should come in around $12 billion. If they landed anywhere close to that number, he became a billionaire almost overnight. But the Match board believed that a fair valuation would be much lower. “If Sean pushes for more without any basis, we will go fully nuclear in response,” Blatt wrote to a colleague. By April, Rad was frozen out of the discussions that were occurring in Tinder headquarters in Los Angeles.

On April 18, Rad wrote Storm Duncan an email about Blatt: “Fuck him. We’re at war. We will destroy him. This is going to be the biggest lesson of his life.” Nine days later, something shocking occurred: An employee filed a report with Match’s general counsel accusing Greg Blatt of misconduct at the December 2016 Christmas party. The employee who filed the report was not, as would be expected, Rosette Pambakian, the alleged victim. The employee who filed the report was Sean Rad. The timing made it appear as though Rad had reported Blatt in order to knock him out of the CEO chair during the valuation process.

Blatt worried that the allegation would leak and expressed his anger to colleagues. A few weeks after Rad reported the Christmas party, Blatt received a disturbing email from a director at the Match Group: The director had invested money in the Fyre Festival and was giving Blatt a heads-up about imminent “salacious” press. But Blatt’s attention was elsewhere. “I have much bigger problems,” he wrote. “Sean has gone off the reservation and is trying to burn down the house. Barry had to just get involved and threaten to go after him for everything that he has, his parents have, and anyone he knows has. It’s really awful. He’s a fucking nut.” (Blatt later told the court that his description of Diller’s threats were only “figuratively true.” Rad testified in court that the “destroy him” email did not refer to the Christmas party allegation.)

If Rad wanted to get Blatt fired before the valuation could be completed, he failed. In July 2017, with Blatt still in charge, Barclays and Deutsche Bank — the banks in charge of mediating between both sides — produced their final report. The final number was a blow to Rad: Tinder was worth only $3 billion.

Shortly after the banks’ report was finished, Blatt announced his resignation. In a draft of a resignation letter, which he never sent, he said the Christmas party was unrelated to his departure, and explained the incident as a “stupid thing” he’d done after having “a few too many drinks.” (Blatt, Rad, Diller, and Pambakian declined to comment for this article.)

At the $3 billion figure, Rad’s options in Match were worth about $360 million. He cashed in, selling all of his shares immediately. He bought a house in the Hollywood Hills for $26 million. He spent another $11 million on Ellen DeGeneres’s old ranch.

Tinder became the most popular dating app in the U.S., and its influence saturated the industry. It was important as a model but also as a cautionary tale, something to correct against: The second-most-popular app in the country, Bumble, was founded by Whitney Wolfe — the Tinder co-founder who had left after being harassed. (Her second act made her a billionaire.) When IAC finally spun out the Match Group as an independent company, the market valuation hit $30 billion. Match’s most valuable property was Tinder.

As Match’s stock continued to rise, Rad couldn’t seem to shake the feeling that Blatt had fleeced him. He told a friend: “Fucking — I can’t — I can’t look at it and be happy. Nothing. Every dollar it goes up makes me more sad and upset.”

Everyone knew that Rad would try to take the Match Group to court. As early as May 2017, James Kim, Tinder’s vice-president of finance, emailed Blatt to warn that “if it’s a number he’s not satisfied with, he’ll basically try to sue.” Standing to make a lot of money if their options were revalued, early Tinder employees — including Kim and Pambakian — joined up with Rad. Despite whatever circumstances had divided them, the promise of a windfall was a powerful unifier.

The core of Rad’s case was that Blatt had lied to the investment banks. In public, Blatt had praised Tinder’s growth, calling the company a “rocket ship.” But in private — to the banks — he said the growth was slowing.

In court, a series of emails seemed to condemn Blatt. “There is already too much revenue,” Blatt wrote to a senior executive, Amarnath Thombre, during the valuation process. “We’ve really goosed this thing beyond what I think it can do.” Then, when Thombre sent him a model that showed new-user registrations increasing, Blatt responded that the numbers should actually be decreasing. “This is unacceptable,” he wrote. “It’s going to totally fuck us. Totally. I don’t know how we didn’t focus on this part of the fucking process. Goddammit.” Later, Tinder’s COO, Shar Dubey, emailed Blatt to say that a new feature was ready to launch: “Likes You,” which allowed users to see who had swiped on them, would probably generate a lot of revenue, increasing Tinder’s value. Blatt responded to Dubey, “I may want to delay it.”

There was also the issue of a slide deck that had been prepared in the spring of 2016 — a “recruiting deck” intended to persuade one of the Valley’s star engineers, Maria Zhang, to take a job at Tinder. To show Zhang how valuable her stock options could become, the deck gave a range of Tinder’s possible future values, from $7.05 billion to $11.75 billion. Rad’s lawyers held up the deck as an example of the conspiracy: Blatt knew the business was worth as much as $11.75 billion when talking to Zhang but pretended it was worth $2 billion when talking to the investment banks.

But the defense had an alternate story for each of the key exhibits. The email about “too much revenue” referred, they claimed, to Blatt’s concern — as the CEO of a public company — that he not overstate projections to Wall Street. “This was unacceptable” expressed his view that Tinder’s rate of growth was slowing even as revenue continued to rise. The delay in “Likes You” was the App Store’s fault. And the recruiting deck — which Match’s lawyers referred to dismissively as “the little deck” — represented nothing more than advertising, big-time talk to entice a new hire.

Rad’s testimony ran over multiple days. The role he played, of an innocent naïf who was robbed by older men, seemed plausible enough given the culture of the Valley, but he kept tripping on his own anger. He wanted to respond in paragraphs when the lawyers asked for “yes or no.” I couldn’t tell whether six jurors would sympathize with him or consider him greedy. He’d already gotten $360 million.

On the stand, Blatt played the role of seasoned public-company CEO who corrected the misconceptions of a disgruntled kid. In response to the allegations that he’d depressed the valuation, he explained the “law of large numbers” to the jurors: He wasn’t saying that revenue was decreasing; he was describing a mathematical law: As the numbers got bigger, they got harder to beat. Luckily for him, the judge had excluded the Christmas party incident from coming into court.

Most commercial court proceedings are unbearable to watch, but Rad v. IAC was different. Weird things happened. The second week of trial, lawyers for IAC got up in front of the judge and announced that they had taken cell-phone pictures of Rad and his lawyer entering a “private room” together during a break in testimony — if true, a violation of rules about witness coaching. Rad’s lawyer responded by asking “what Orwellian reality we’re living in here that people are taking pictures of us,” before confessing that he had entered a room with Rad: “I walked into the men’s room, and at the urinal was Mr. Rad.”

In another long detour, Rad’s lawyers accused Greg Blatt of having “forcibly grabbed” Rad’s arm in the hallway during a break, then “approached two women on our team, and acted so inappropriately and shockingly in a way to intimidate … we were so shaken by it.” A full hour went by in court as the two sides debated (a) whether Blatt had done these things (Blatt said no; Rad’s lawyers said yes), and (b) if he did, what should be done about it. The mood seemed halting, disjointed, and vicious. The ventilation in the courtroom was poor, and it was hot.

One thing that kept me glued to the screen was my own confusion: I didn’t understand why any of these gambits would help either side win over a jury. The material was so arcane to begin with, and the sniping so intense, that by the end of the third week I had absolutely no clue what the jurors would decide. My instincts for jury decisions — terrible on a good day — had been reduced to absolutely nothing.

That they were effectively careening toward a multibillion-dollar dice roll was a realization that seemed to settle on the lawyers just before Thanksgiving weekend. For several days, in phone calls and Zoom meetings, they began to negotiate a settlement — taking the process back from the hands of the six average New Yorkers in the jury box and into their own. While we were all fixated on the courtroom, the real business was transacted offstage, where the stakes weren’t emotional but only numbers on balance sheets. According to the settlement, Match agreed to pay $441 million to Rad and his co-plaintiffs.

The day of the settlement, Match’s stock price barely changed at all; it’s still a $35 billion company. Diller remains a billionaire. Greg Blatt went to work for a biotechnology company in Dallas. And Rad, citing the “trauma” of the valuation process, went to work on an app that helps users relieve stress.

In December, I called a former Tinder employee who had worked for the company in 2017 and knew Sean Rad. There was one thing I still didn’t understand about the corporate revenge story I had just witnessed. When you accounted for all the costs that Rad had incurred — the litigation-financing agreement, all the lost hours, the fact that he’d have to share the settlement with multiple co-plaintiffs — $441 million fell far short of the total he wanted. What was the point?

“Sean went from nothing to this,” the former employee told me. “He captured this one idea. It’s his baby. ‘What if we did this thing that made it easy for people like us to meet girls in bars?’ He’s an awkward L.A. guy, and he did this one thing.”

“Okay,” I said, “but he already made $400 million. Some people might say, ‘Who cares about another $100 million, even another $500 million?’”

“It’s irrelevant that he’s got $400 million,” the former employee said, in the tone you use with someone who just doesn’t get it. “Because it’s human nature to think about what you’ve lost.”

This post has been updated.