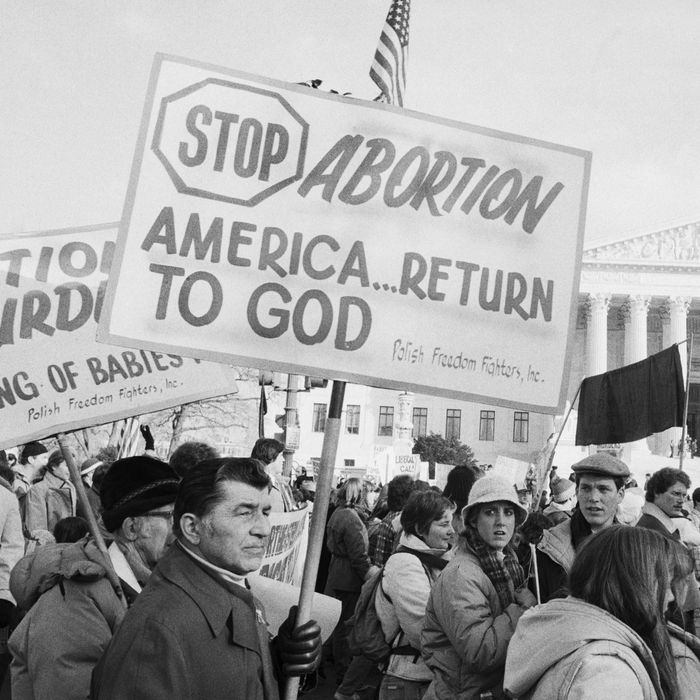

For decades, the anti-abortion movement depicted the nation in stark, bloody terms. Abortion is a genocide, a new Holocaust, a contemporary moral crisis like no other, they claimed. The procedure was not only the product of an individual woman’s sin but also a symptom of a culture gone to hell. “Why is a human life worth saving? Why is it worth the trouble?” the late theologian Francis Schaeffer wondered in the first episode of his influential 1979 series Whatever Happened to the Human Race? Many people, Schaeffer claimed, no longer believed that human life held much value at all; the era of legal abortion ushered in six years earlier with Roe v. Wade had led to infanticide, he said without evidence. Through such baseless claims, and the influence of radical rhetoric, abortion opponents such as Schaeffer mobilized a powerful political movement. Now they have the outcome they seek: Roe is no more, and in much of the country, it will become much more difficult to access abortion. If Schaeffer was right, then a great injustice is over. Human life is worth saving again.

But the early days of life after Roe suggest quite a different outcome. The case of a 10-year-old Ohio girl, pregnant through rape, captured international attention and threw the right wing into disarray. Because of Ohio’s strict abortion laws, she had to travel to Indiana to receive treatment. The first instinct of many in the conservative press was to either insinuate or insist outright that the story was fiction. After the arrest of the girl’s alleged rapist corroborated the story, abortion opponents faced a difficult choice: They could admit that they wanted to force a child rape victim to give birth or they could pretend she qualified for a rare exemption to Ohio’s abortion restrictions. (She likely doesn’t, according to reporting from legal journalist Chris Geidner.) One abortion opponent adopted a third position during a congressional hearing.

“If a 10-year-old became pregnant as a result of rape and it was threatening her life, then that’s not an abortion,” Catherine Glenn Foster of Americans United for Life told Representative Eric Swalwell. “So it would not fall under any abortion restriction in our nation.” She is incorrect on both counts. Any procedure that terminates a pregnancy is an abortion. A life-saving termination, such as in the case of ectopic pregnancy, is an abortion. A termination performed on a 10-year-old girl is an abortion — and ends a human life, by the anti-abortion movement’s own standards.

Jim Bopp, the powerful general counsel for the National Right to Life, offered a more honest view of the situation in an interview with Politico. “She would have had the baby, and as many women who have had babies as a result of rape, we would hope that she would understand the reason and ultimately the benefit of having the child,” he said. Consider both the psychological and physical implications of Bopp’s statement: In order to preserve a fetus, a child must remain pregnant. She must live, daily, with the reminder of her rape. She must feel pregnancy deform her tiny body. She must then give birth, which can be traumatic for fully grown adults, and either raise her rapist’s child or surrender it for adoption — a decision that imposes its own set of psychological burdens, as adoptees and birth mothers have testified.

“The logic of abortion has been that you have to pick a side between the baby or the mother,” the Catholic writer Leah Libresco Sargeant claimed in a piece for the New York Times. Yet this is precisely the logic imposed by the anti-abortion movement. In the view espoused by abortion opponents such as Bopp, there is only one side to take — that of the fetus. The pregnant adult or child must sacrifice their own well-being to carry a pregnancy to term. Libresco Sargeant dreams of a world where “we can offer more love and material support to mothers and children, especially in the hardest cases,” but to abortion opponents, love is a weapon. Nothing can redeem the wounds it inflicts.

The anti-abortion movement has never acknowledged the violence it engenders. This applies both to direct acts of terrorism, to bombed-out clinics and murdered doctors, and to the everyday violence endorsed by its most thoughtful members. Proponents of a consistent ethic of life oppose the death penalty and support an expanded welfare state; they are also prepared to inflict grotesque violence on pregnant children and adults, as the last few days have shown. Even people who are not pregnant are experiencing the debilitating effects of a nation without Roe: The Los Angeles Times has reported that people with autoimmune disorders have been denied methotrexate, a common and effective drug, because there is a chance it could cause miscarriage.

A world without the right to abortion is a world filled with suffering. Abortion opponents are uniquely unprepared for the reality they created. The first major ethical dilemma to appear post-Roe, the case of the Ohio girl, has scattered them. They can’t decide if the story is a hoax or if the abortion is an abortion at all. Still others, like Bopp, affirm the innate cruelty of the anti-choice position. Such indecision insults the people they would force to remain pregnant; it is the mark, too, of a morally unserious movement. Abortion opponents have had decades to anticipate the “hardest cases” they would produce. Now the post-Roe era shows them to be fantasists at best and liars at worst. Not only is there no material support forthcoming in the states most likely to ban abortion, but the mere end of Roe did not transform unwanted pregnancy into a blessing for mothers. It more closely resembles a punishment. After warning for years of a great moral crisis, abortion opponents inflict their own on the world. They cannot answer the very questions they pose. To paraphrase Schaeffer, why is a little girl worth saving? Why is she worth the trouble? Because she is not an abstraction. She is not potential but a person. She is real.