Quick quiz: How many streaming services do you subscribe to? Okay. Now how much do they each cost? How about together? In my house, the domestic rota includes regular streaming audits: Showtime is out. Hulu is back in, at least until we watch The Bear. Criterion? Be honest with yourself. Somehow, the overall bill keeps creeping higher.

Streaming sprawl has infected the small talk of last resort — “What are you watching these days?” — converting straightforward show recommendations into reluctant sales pitches for yet another $8.99 service with four exclusive shows, one of which is worth streaming. Cue the rueful, worn-out jokes about how, once you add back sports streaming, you’re basically paying for cable. There’s a good chance you do that anyway!

One reason streaming feels like a mess is that it really is a mess after more than a decade of intense, flailing competition between tech companies and legacy-media firms to plan for the post-cable future, resulting in the launch of dozens of streaming options and unprecedented spending on new programming. It’s also experiencing its first real slowdown. Netflix, streaming’s longtime standard-bearer, saw its subscriber base in the U.S. and Canada grow by just 100,000 users last quarter after losing 1.28 million and 600,000 in the two quarters prior — its first losses in over a decade. These declines were a shock to Wall Street but, again, probably didn’t sound so weird to anyone with an internet-connected TV and an awareness of Stranger Things. It’s Netflix! Who is left to sign up? (The company’s reputation in the industry has been slipping as well, as Hollywood insiders told New York earlier this year.)

There were layoffs. Netflix implied that spending on new content — while still breathtakingly high — would be “moderated.” (It also estimates that its competitors, which have been spending lavishly to catch up with Netflix, which is profitable, are collectively losing at least $10 billion a year.) It emphasized, as every American tech company does when it reaches a domestic plateau, that it still has lots of room to grow overseas.

Netflix announced two changes to the product itself. First, it will start cracking down on account sharing, potentially locking out millions of viewers and asking them to pay up. Oh, and also, by the way, no big deal, it’s also going to start showing ads.

There are plenty of caveats here. Ads will be shown only to customers of a new, cheaper tier of the service — $6.99 a month — and only on certain content (albeit most of it). Netflix told investors it didn’t expect users to switch to the new tier but rather hoped it would bring in new subscribers, perhaps some of the ones getting booted from sharing. But industry Netflix watchers knew this was a big deal. Virtually every streaming service either has introduced or is introducing an ad-supported product. Hulu always had one. Disney+ is adding one. Peacock, Paramount, and Discovery+ have them. Amazon has one, sort of (ever heard of Amazon Freevee?). Even Apple is reportedly in conversations about advertisers for a new tier of Apple TV+. Netflix is making a serious concession here. It isn’t doing something other streamers would try to copy. It’s following the pack.

Netflix hasn’t just been a streaming service without ads — it also practically declared itself an anti-ad TV company intent on finishing the job TiVo started and a tech firm that would stand against the internet industry’s prevailing model. “We want to be the safe respite where you can explore, you can get stimulated, have fun and enjoy, and have none of the controversy around exploiting users with advertising,” CEO Reed Hastings said in 2020. This wasn’t new messaging. “We, like HBO, are advertising free,” he explained the year before. “That remains a deep part of our brand proposition.” (HBO Max introduced an ad tier the next year.)

In a 2014 New Yorker profile more or less heralding the end of traditional broadcasting, Netflix’s then-VP of content promised an era of creativity free from crude ad-driven demands:

The creative experience is different, too, she said; making “House of Cards” was akin to making “a thirteen-hour movie.” There was no need to recap previous episodes or to insert cliffhangers. Increasingly, show creators can work without executives’ notes, focus groups, concerns about ratings, and anxieties about whether advertisers will resist having their products slotted after a nude scene or one laced with obscenity.

Streaming companies have executives, too, of course, and show creators have become sensitive to the particular limits of their new environments, metabolizing them into jokes about “the algorithm” and a new generation of clueless suits, sketching a new “TV about TV” meta-comedy in the tradition of The Larry Sanders Show and 30 Rock except with more jokes about data science. On HBO, Curb Your Enthusiasm ran with a plot about Hulu for a season, and Barry took savage swipes at a thinly veiled Netflix.

On Hulu, you can watch Reboot, a sitcom about reviving an old sitcom for Hulu, which features gentle jokes about a data-obsessed but well-meaning “vice-president of comedy” who is “new to humor.” Or, on Netflix itself, you can watch BoJack Horseman, a withering assessment of the entire entertainment industry including streaming, of which Hastings is known to be a fan. (BoJack’s creator revealed, last year, that Netflix asked him to cut a joke that could have offended another more famous showrunner.)

These are familiar struggles represented in a familiar form, but they refer to a genuinely unusual time in TV production during which Netflix and its competitors spent enormous amounts of money at a very high rate on a staggering range of programming intended to achieve suddenly different goals.

It was a boom, and maybe a bubble, in TV and certain sorts of film production resulting from new priorities and incentives — namely, an applike emphasis on acquiring as many new users as possible as quickly as possible, by any means necessary, and worrying about the rest later. Streamers figured out that while plenty of content created for linear television was popular on streaming, not all of it was useful for driving sign-ups or keeping people subscribed. So commenced a decade of trying basically everything to unlock the secrets for getting subscriptions, which, to viewers, manifested as chaotic glut. Endless prestige shows! Experimental trash shows! Super-niche shows! Super-broad shows! Reality seasons released all at once. Reality seasons spaced out! Live sports? Sure, live sports! Shows ripped straight from TikTok! Vanity projects from legendary directors! Shows purchased from overseas! Shows about America with a capital A. Good docs, bad docs, long docs, short docs. In the space of a decade, for people who primarily watched streaming, “television” was recomposed into something familiar yet substantially new. Companies spent tens of billions of dollars making shows not to get ratings, which are basically a proxy for the ability to generate advertising revenue, but to convert subscriptions. This change was, as described in Vulture’s look back at the 2010s, creatively and financially profound:

It quickly became clear to writers, directors, and producers that the standard 60- or 30-minute episode was arbitrary, opening up all sorts of new possibilities for structuring stories and delivering fresh dollops of characterization and plot.

Then came the boom in original content, which begat the rise of not only Netflix, but Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, YouTube, Apple TV+, and the juggernaut Disney+, all treating TV as a way of drawing traffic and enticing new subscribers (the premium-cable business model all over again, somewhat modified). The tail wags the dog now, to such an extent that cable channels and networks alike have essentially become branded production houses supplying shows to streaming platforms that increasingly seem to be the only place people are interested in watching TV anymore.

Recent setbacks reasonably led to predictions that Netflix would double down on what has recently worked best to drive subscriptions (Stranger Things, Stranger Things, Dahmer, Stranger Things). But the company’s announcements, particularly the addition of the ad tier, hint at another sort of future for streaming — one that some of Netflix’s competitors might be eager to see. It would be a retreat, in some ways, to an older way of making TV.

Streaming used to work something like this: People subscribed to what they wanted, conscious of the cost, and canceled services if they were too boring or too expensive. Streaming currently works like this: People subscribe to what they want, conscious of the cost, and cancel services if they are too boring or too expensive, or maybe they consider a cheaper version of the service supported by ads. A large majority of Hulu viewers opt for the cheaper ad-supported subscription, and executives at Disney, which owns Hulu, have said they expect similar numbers when Disney’s ad-supported option debuts later this year. Streaming subscriptions add up quickly, but so do advertising discounts. A household subscribed to the standard plans for the eight most popular services could, at current prices, cut its bill from about $85 to about $45 by downgrading. Streaming inflation is real.

It’s not much of a leap to imagine that streaming could work like this: Many people subscribe to most services because they’re ad supported and cheap or even free, and a smaller number of people choose to pay to get rid of ads or to get access to premium programming. Avoiding ads becomes a luxury again — not unlike the deal you got with premium cable. Seeing a lot of ads and shelling out for various subscriptions would be the default.

From a user perspective, it’s a bit of a letdown — a return to the world we were told we were escaping. But from a corporate perspective, it’s better aligned with the industry’s new laser focus on “revenue per user” over subscriptions. “If you’re going to continue investing in content, the best way to increase the average revenue per user, in a way that feels familiar, is ads,” says Julia Alexander, the director of strategy at Parrot Analytics, an entertainment-research firm. “The idea of any streaming service saying the future of TV has no ads can only be said from a place of monopolization.” Today, Netflix is beset by competitors, many of which aren’t tech companies but subsidiaries of old-media conglomerates, which are eager to either build a bridge to the internet for their existing advertisers or more broadly recapture past glory. “The companies that are best positioned to enter this moment are those that have worked with advertisers for decades,” says Alexander. “They know that TV was always about advertising.”

This would be a scenario in which advertising isn’t just more visible to viewers, it’s also once again integral to how TV is produced, where something like old-school ratings come back into play and advertisers’ needs and demands are taken into account from before a show’s conception through to its cancellation. (Netflix’s advertising announcement was accompanied by news of a new partner: Nielsen!) Netflix, a company with an internal dashboard that algorithmically estimates a show’s total value to the firm, will have new information to factor in: how much content is worth to advertisers now and in the long term — that is, how well it converts customers for other companies, not just for Netflix. Just the sort of thing the company said we were done with in 2014.

This could suggest a return to types of shows that, while still commanding high ratings on linear TV, seemed to be on their way out: network procedurals and sitcoms. “When you look at Netflix domestically, shows like Criminal Minds, NCIS, and Grey’s Anatomy are consistently some of the most in-demand shows on the platform,” says Alexander. These are high-retention shows, meaning that while they don’t drive many sign-ups, they seem to help keep people around and streaming and, potentially, watching ads. They’re also types of shows that Netflix hasn’t successfully created itself. “You have to give them five years,” Alexander says, “but Netflix’s efficiency model has dictated that a show needs to perform in the first few years.” They also might become more expensive — or impossible — to license from companies with growing streaming services of their own. (Netflix’s nine-figure pursuit of Friends, which it lost to HBO Max in 2020, is instructive here, as was its awkward attempt at a traditional network sitcom, The Ranch.)

There are other clues about the streaming world to come. Absent from most media narratives about streaming and TV habits are three massive and growing services that are free to watch and supported by ads: Tubi, which is owned by Fox and has, at last official count, 51 million users; Paramount’s Pluto TV, which has an on-demand catalogue and some live channels and counts more than 70 million subscribers; and the Roku Channel, which is available for free to anyone with a Roku device, of which there are hundreds of millions. (There’s also Crackle, formerly owned by Sony but now owned, alongside Redbox, by Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment, as in the books, which, in case you were wondering, is a publicly traded company valued at more than $100 million.)

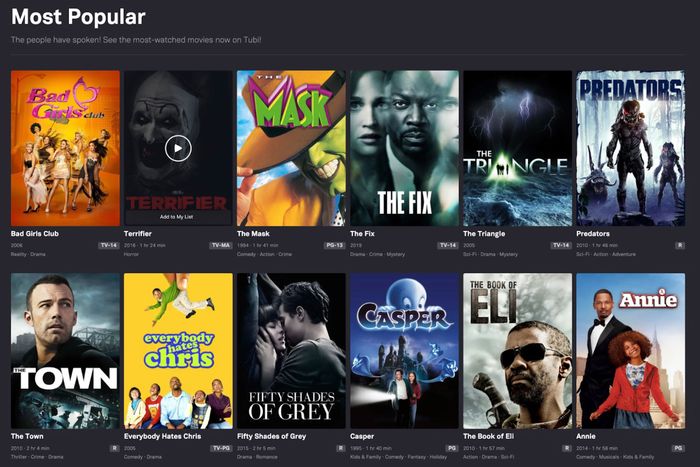

Tubi, in particular, offers a vision. It’s a popular service with plenty of fans and a compelling catalogue. Its most popular titles, at the time of writing, are well-known but older Fox family movies, reality shows, and sitcoms:

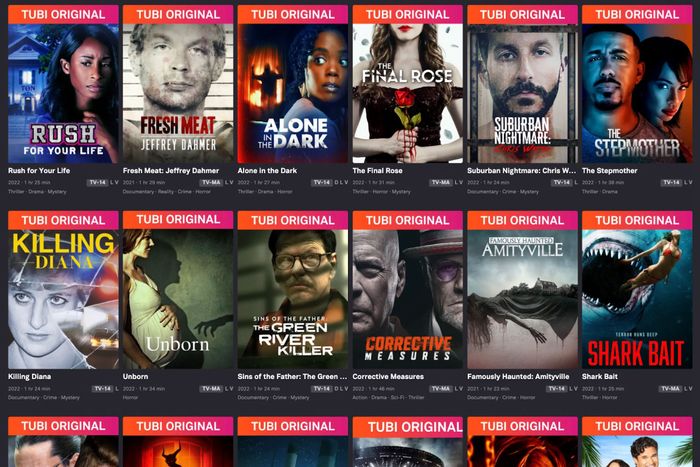

Tubi also releases some exclusive content of its own, offering a snapshot of one future of TV in which most things are free, viewers expect ads, and advertisers expect reach and value for their money.

True crime, geezer teasers, and documentaries ripped from the headlines. This ad-centric future of TV looks a little like Netflix around 2022, but it looks more like something older: basic cable.