You know things are serious when David Solomon, the Goldman Sachs CEO who spent the summer DJ-ing at Lollapalooza, hasn’t posted on Instagram about his music since August. The largest economies in the world — the U.S., China, the eurozone — are teetering on the edge of recession, and the coming months, maybe the next year or so, will probably be a time of rising unemployment, spreading bankruptcies, and the price of everything remaining high. Add to that a European land war and OPEC+ cutting oil production, and you’d expect Wall Street’s biggest banks would be hunkering down to protect themselves from a wipeout. To an extent, they are. This has been a rough year, with dealmaking all but halted, the stock market erasing two years of gains, and rampant inflation throwing the global economy off-kilter. Wall Street banks are designed to understand the economy better than anyone else. Assuming they do have some special insights, it’s worth reading their real-world-concern level: Just how freaked are the masters of the universe right now?

Well, that’s a bit complicated. Observers of the financial world have noted that there is currently no consensus view among the people who lead America’s biggest banks. For some, the economy is about to get much scarier, while others argue that consumers are still basically fine and that the U.S. may scrape by with relatively light economic damage.

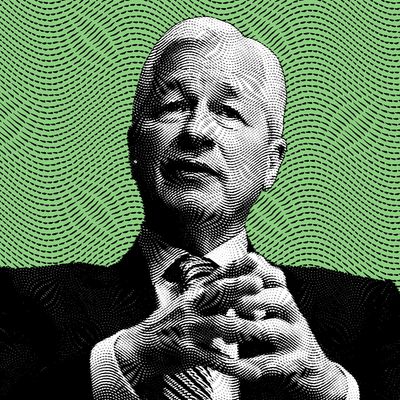

The lead spokesman for Team Fear is Jamie Dimon, the longtime head of JPMorgan Chase, which is the largest bank in the U.S. by just about every measure. Back in June, Dimon warned about an incoming economic “hurricane,” and he doubled down on that prediction last week when he said the country would likely be “in some kind of recession six to nine months from now.” From a certain angle, his bank is definitely preparing for some kind of downturn as it’s sitting on a mind-boggling $1.2 trillion in cash, or almost $4 million for each of its 288,000 employees (though that headline number is a little complicated — more on that later). And Dimon certainly has experience with this kind of thing. He’s the only CEO of a major bank who lived through the 2008 financial crisis, and he pioneered the idea of a “fortress balance sheet” that would protect a bank from going under in times of emergency.

And he’s not alone. Solomon — whose bank saw a 43 percent drop in profit last quarter — said on Tuesday there’s “a good chance we have a recession in the United States.” At the same time, he’s preparing to reorganize Goldman Sachs “toward businesses that generate steady fees in any environment,” according to a Sunday Wall Street Journal report. The idea here is that some businesses, like trading or investment banking, do better when the economy is good, and this reshuffling is meant to insulate the venerable institutions from a coming period when companies don’t want to go public or rich investors don’t want to trade stock. One interesting detail here is about Marcus, Goldman’s six-year-old experiment in online banking for the masses. Its consumer unit is famously expensive and reportedly under a regulatory investigation, but it was supposed to be a way to bring in cash and make the company less risky. It will have free rein no more. After the reshuffling, it’s getting new management and will be part of a broader group of businesses that make more money, like managing the assets of institutions and wealthy clients.

This matters because not all money is equal — and you can get a sense of what banks think will be important in the future. Goldman didn’t seek out money from the proletariat for the first 147 years of its existence; after the Marcus business started, it was paying some of the highest interest rates among all banks for those consumer dollars, at a time when interest rates were about rock bottom, in an effort to build up its base of depositors. Doing that is expensive for banks, though, as one of the surest ways they can profit is on the difference between the interest they get paid from money they lend and what they pay out for deposits. But now, the bank’s “incentive fees” for the unit housing Marcus — basically what it pays out to keep customers happy — have fallen 83 percent in the past year. The message is clear: While Goldman was glad to spend money to bring in new retail-banking clients when rates were low and times were easy, there’s less tolerance today for anything but the leanest of profit-making businesses.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. JPMorgan, Goldman, Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo have reported that they’re still making plenty of money, and analysts are expecting them to have to set aside only $5 billion or so for busted loans — one of the key ways a bank would get hurt during a downturn. And Brian Moynihan, CEO of Bank of America, is far more upbeat than Dimon is about the state of the world. “The customers’ resilience and health remain strong,” he said on an analyst call Monday morning. And while Dimon has made plain his fear about the future, he has pointed out that right now people are spending money. Even Goldman’s annual round of culling was fairly light as layoffs go. (Bonuses, however, are probably not going to be anything like last year’s absolute bonanza.)

To get a better sense of how to resolve all these data points, I talked with Mike Mayo, a financial analyst at Wells Fargo who’s known for challenging Wall Street CEOs, particularly Dimon, during the usually genteel quarterly earnings calls. Last week, Mayo got into a back-and-forth with Dimon, arguing that JPMorgan Chase wasn’t putting away enough money to prepare for the wave of bankruptcies that could come with a recession. “I’ve had some trouble reconciling Jamie Dimon’s actions with his words,” Mayo told me. “His words are like, A hurricane is coming, and it can be very destructive, but his actions are as if he’s buying kayaks, a surfboard, a WaveRunner, and a new swimsuit to prepare for a sunny day.”

Mayo is referring to the fact that federal regulators require banks like JPMorgan to set aside money for different businesses to prepare for losses — essentially segregating some cash so it can’t be put at risk. While Dimon is technically sitting on $1.2 trillion in cash, the money that’s set aside for these worst-case scenarios for bad loans is much less than that, about $268 billion in capital. And these reserves are slippery, often changing quarter to quarter. At one point last week, Dimon chastised an analyst who wanted more information about the money set aside for potential loan losses. “Honestly, I wouldn’t spend too much time on it because it’s not a real number. It’s a hypothetical, probability-based number,” he said.

But CEOs like Dimon have the luxury to say one thing while their bank does another. Since the passage of a package of reforms in 2010, banks have had to set aside more money to prepare for not only a recession but a complete systemwide failure. “It’s night and day from before the great financial crisis to today, from an oversight and financial-preparedness level,” Mayo said. The analyst noted that most people who work on Wall Street have been through only one major recession, in 2008, and that a more run-of-the-mill recession would be much more manageable for Wall Street. “The banks are signaling that they’re preparing for tougher times,” Mayo said, “but they’re not freaking out.”