In the 2020 election, Arizona backed Joe Biden over Donald Trump by 0.3 percentage points. This made The Grand Canyon State nearly four points more Republican than America as a whole. Had the national environment been a tad less favorable for Democrats, Arizona would likely have remained a red state.

Thus, in the election’s aftermath, the challenge facing Arizona’s two Democratic senators was clear: To maximize their odds of reelection, each would need to find a way of appealing to independents and moderate Republicans.

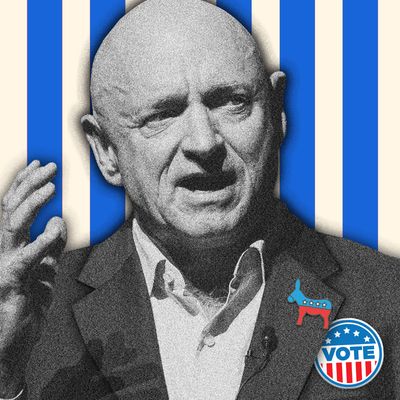

This was especially imperative for Mark Kelly. Elected in 2020, the former astronaut won his Senate seat in a special election. He therefore would need to face voters again in 2022, when Democrats were all but certain to do worse than they had in 2020; historically, the president’s party almost always loses seats in midterm elections.

Kyrsten Sinema, by contrast, didn’t need to face voters until 2024, a general-election year when Democrats could plausibly replicate their national margin from four years earlier.

And yet, it was Sinema — not Kelly — who decided to comport herself as a thorn in Biden’s side.

Kelly rubber-stamped the president’s top legislative priorities, lining up behind his Build Back Better bill and advocating for reforms to the filibuster, which would have enabled Democrats to pass voting-rights legislation with a simple majority vote.

Sinema, meanwhile, single-handedly gutted Biden’s plans for raising taxes on corporations and hedge-fund managers and withheld support for his partisan spending bill for even longer than Joe Manchin did. The former Green Party activist also styled herself as the filibuster’s staunchest defender.

Which isn’t to say that Kelly’s approach was diametrically opposed to Sinema’s. Arizona’s junior senator did break with the White House on several issues. Most consequentially, Kelly sought to shore up his support among Arizona business owners by torpedoing a progressive nominee to the Labor Department. And he also criticized Biden’s opposition to new oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, and the president’s supposed weakness on border security. Nevertheless, Kelly’s dissident gestures were far fewer and less consequential than Sinema’s.

And he’s poised to win reelection by a large margin, anyway.

As of this writing, only 82 percent of Arizona’s votes have been counted. But given the size of Kelly’s lead, and the likely composition of the remaining vote, the Cook Political Report’s Dave Wasserman believes that Kelly has won.

And he’s on pace to win by more than 5 percentage points. In 2018, when Democrats won the national popular vote by 8 percent, Sinema won her Senate race by 2.4 points. The precise figures could change as the final votes are counted. But right now, it looks like Democrats lost the national popular vote on Tuesday by a considerable margin and Mark Kelly nevertheless managed to win by more than twice as much as Sinema did in a “blue wave” year.

Of course, there are plenty of uncontrolled variables between these two test cases. Kelly was running for reelection, and therefore enjoyed the advantage of incumbency. He was also running in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s gutting of Roe v. Wade in a state where abortion rights are under attack. And he had the good fortune of drawing a political neophyte with psychopath vibes as his opponent.

But Kelly wasn’t the only vulnerable Democratic incumbent who toed the party line on Biden’s agenda and proceeded to outperform their party’s national margin. New Hampshire senator Maggie Hassan not only supported Biden’s Build Back Better plan, but also endorsed the president’s controversial cancellation of student debt. She won reelection by more than nine points.

Votes are still being counted in Nevada but, as of this writing, Catherine Cortez Masto is favored to win reelection in the Silver State after serving as a loyal soldier for the Biden agenda. Raphael Warnock was an unabashed advocate for Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID stimulus, his proposed democracy reforms, and his student-debt cancellation plan. And Warnock won a plurality of the vote in Georgia Tuesday. In other states, that would have secured the former pastor’s reelection. Instead, he will enter a runoff election as the race’s favorite.

Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania, John Fetterman won his Senate race by more than four points. The Keystone State’s lieutenant governor wasn’t in a position to vote for Biden’s agenda over the past two years. But he still advocated for the abolition of the filibuster, for the sake of getting more of the president’s progressive policies into law. Thus, he portrayed himself as the opposite of a check on the president’s power. And yet, he won his state by a larger margin than Biden did in 2020, despite the fact that the national environment this year was far worse for Democrats.

For anyone who believes that Democrats shouldn’t govern from a defensive crouch, these are heartening results. Given the party’s bare majority in the Senate, Biden accomplished a remarkable amount legislatively during his first two years in office. Democrats passed one of the largest stimulus bills in American history — and then the largest climate bill ever — with just 50 Senate votes. Were it not for Sinema and Manchin, Biden could have gotten more. Yet their intransigence was less remarkable than the loyalty of Kelly, Hassan, Warnock, and Cortez Masto. It is quite normal, historically, for vulnerable incumbents to derail their party’s legislative priorities. What’s unusual is that so many “frontline” Democrats agreed to play ball on an ambitious, partisan agenda.

Had these Biden loyalists lost reelection Tuesday, purple-state Democrats might have concluded that toeing the party line on major legislation wasn’t worth the trouble. The fact that they all (apparently) got more votes than their opponents — at a time when their president’s approval rating was historically low and inflation was historically high — might stiffen some front-liners’ spines the next time Democrats have a trifecta.

Of course, we don’t know whether Kelly, Hassan, & Co. would have performed even better had they joined Manchin and Sinema in carving up Biden’s agenda. One can find some evidence to support that hypothesis. Maine’s Jared Golden was the only House Democrat to vote against the Build Back Better bill. And, as of this writing, he is on pace to win reelection by more than three points, in a district that Donald Trump won by eight points in 2020. In other words, he did 11 points better in his district than Biden did. No swing-state Senate Democrat improved on the president’s performance by that much. Had Tim Ryan bested Biden’s mark by 11 points in Ohio, he would have defeated J.D. Vance.

So, there is some reason to believe that defying one’s party on major legislation can be electorally expedient. But Tuesday’s results nonetheless suggest that, for Democrats in purple states, it is not politically necessary. Sinema’s sabotage of the Biden agenda cannot be justified as the price of her political survival.

None of this means that purple-state Democrats don’t need to worry about placating popular opinion. In their campaign ads, virtually all of the party’s swing-state candidates performed gestures of moderation. Even Fetterman, a former Bernie Sanders supporter, portrayed himself as a staunch advocate of more police funding and fracking. The question isn’t whether Democrats need to appeal to voters more conservative than their base in order to win. Rather, it’s how Democrats should go about doing that.

And Tuesday’s results suggest that they can achieve that objective without obstructing their party’s top governing priorities.

Those results were complex and unusual. There was far more regional variation in Democrats’ performance than in recent election cycles. If you only looked at the results in New York and Florida, you would have thought that 2022 was a “red wave” election. If you only looked at Michigan and Colorado, you might have expected Democrats to easily win the House. Still, there does seem to be one fairly consistent pattern in the results: Democratic incumbents in close races greatly outperformed those in safe districts.

In districts where Democratic incumbents were heavily favored to win reelection, the party’s share of the vote declined by 2.5 percent from its 2020 level; in districts rated as “toss-ups” or “lean Democratic,” the party’s vote share declined by only 0.4 percent, according to a preliminary analysis by David Shor of the Democratic data firm Blue Rose Research.

One explanation for this remarkable discrepancy is that Democrats spent a lot more money — and aired a lot more TV ads — in competitive districts than they did in noncompetitive ones. And the party (and its associated PACs) had a lot of money to spend; 2022 saw more political spending than any midterm in U.S. history by a $3 billion margin.

If poll-tested campaign ads can do this much work for Democrats, then the party’s front-liners don’t need to differentiate themselves from their party in more substantively costly ways. Or, at least, a front-liner like Kyrsten Sinema — who represents a purple state, rather than a red one — has little excuse for obstructing tax increases on the wealthy, price controls on prescription drugs, expansions of the social safety net, and other broadly popular reforms.

Democratic incumbents won’t always have the benefit of running against heinously unpopular Supreme Court decisions. But then, they also won’t always have the burden of presiding over 8 percent inflation and campaigning in the shadow of a historically unpopular president.

The point of politics, in my estimation, is to win power and then use it to improve the lives of ordinary people. Declining to use one’s power for progressive ends can only be justified if doing so is imperative for preserving that power. In debates over political expediency, those who fight to withhold aid to impoverished children, or care for the elderly, or labor rights for workers assume the burden of proof. Given Tuesday’s results, Sinema can’t meet it.