This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In March, TikTok user scotty..pimpin posted from inside an anonymous run-down shipping facility. In the video, packages fall from a conveyor belt down metal slides, like a luggage carousel in reverse. Things are getting backed up. There are Amazon packages, generic cardboard boxes, and a variety of polyethylene packets. Mostly, there are the orange bags. “I’m gonna need y’all to stop ordering Temu shit,” the poster says. “Because what the fuck is all this? This is all work!”

At other nodes in America’s vast logistics infrastructure, workers are also noticing the orange. “All of a sudden it feels like 25 percent of my route is getting stuff from there,” a postal carrier wrote on Reddit last month. “Our package volume has literally tripled since people in town found out about them,” responded another. “I fucking hate Temu,” wrote one. “When I saw their ad during the Super Bowl, I just thought to myself, ‘fuck.’”

@scotty..pimpin overworking us with #temu

♬ original sound - Scotty

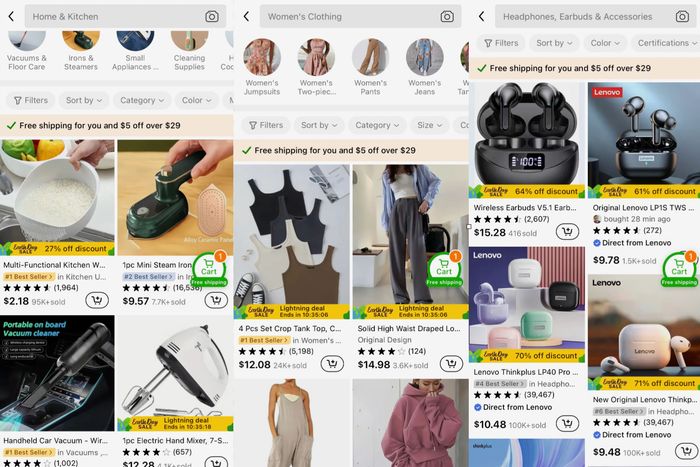

As Temu packages flooded delivery routes, ads for Temu flooded Americans’ smartphones, confronting them across social media and trailing them on search engines, with pictures of chaotic assortments of products — earbuds, wigs, dresses, auto parts, muscle massagers, fake Crocs — tagged with extremely low prices. Temu, a subsidiary of Shanghai-based Pinduoduo, an e-commerce platform with more than 750 million customers in China, launched in September 2022, and within weeks was the most-downloaded shopping app in the iOS App Store. In November, it climbed to the top of the overall App Store charts, above apps like TikTok, Google, and Instagram, where it remains today. Tens of millions of Americans had tried Temu by the time the Super Bowl ad made its self-consciously crass pitch — featuring a brief shot of a happy warehouse employee — to the rest of America: Shop like a billionaire.

Temu seemed to come out of nowhere, and now it’s everywhere, its customers summoning $5.79 yoga pants, $27.98 doorbell cameras, and $10.29 garment steamers by the thousands, directly from factories in China to their front doors within a week or two. In some ways, Temu could not be more out of step with some current trends in the American market, where delivery times are all-important, name brands carry enormous weight, and sustainability and ethical sourcing are marketing fodder. Like TikTok, it’s a corporate sibling to a major Chinese internet platform competing with entrenched American giants, which means it faces potentially existential political risks.

But Temu also represents the culmination of some much larger — if less conspicuous — trends that have been remaking the entire American economy for decades. American retail has long relied on imports from countries with cheaper labor and human-rights practices ranging from questionable to disturbing. The messy and often exploitative processes of overseas manufacturing are concealed behind domestic branding and acknowledged, if at all, with a sticker, a tag, or maybe some fine print. Domestic online retailers — most notably Amazon but also Walmart and Target — have spent the last decade outsourcing not just their products but their entire e-commerce operations to third-party sellers, many based overseas. Temu’s underlying proposition is brutally simple: If America’s retail giants are becoming mere middlemen, why not just cut them out?

Using Temu doesn’t really feel like shopping in the sense that one shops at a supermarket or a mall or a big-box store, or even on most e-commerce sites, moving from place to place, browsing a coherent selection, and then making purchases informed at least in part by conscious intentions. You can search, and you can explore different categories in which you’ll find thousands of products, but Temu is, from the first moment you open it, unapologetically hustling you.

To engage with Temu is to be cornered in conversation with an AI-powered salesperson who is ushering you past endless tables of assorted goods to sell, right now, with escalating special offers, chained promotions, exclusive limited-time discounts, and lots and lots of free stuff. In the space of a minute, an initial buy-seven-get-three-free promo morphs into a buy-four-get-two deal; “Gifts” pile into your inbox, nudging you through casino-style pseudo-games promising free products, and even cash, in exchange for inviting friends; $2 products that arrive later than expected result in $6 shopping credits. In any other context, a single one of these sales techniques would read as scammy and ridiculous. In Temu, they combine into a totalizing and strangely compelling promotional experience, where prices and timers keep ticking down while your account’s various credits — cash, tokens, invites — keep ticking up, suggesting some sort of climax: a payout or, much more likely, a tiny first purchase of just a few dollars. Lots of American retailers have dabbled in gamification to draw users back to their sites and apps, to make them feel like they’re getting a deal, and to nudge them closer to the checkout screen; Temu, like Shein, draws from promotional techniques that have been used to great effect by retailers in China, where such gamification has been common for years.

Temu isn’t done with you when you close it — it’s one of the most relentless notifiers and emailers I’ve ever encountered in more than a decade of professionally installing weird new apps on my phone. There is never not a sale or a special gift or a new promotion or a recommendation. Temu’s aggressive promotions mean that a lot of those orange bags are being flown across the world for free.

This version of Temu — the version you encounter first that runs in the background at all times, beckoning you back, and greets you with endless machine-learning-generated feeds of products based on data collected from your previous browsing habits — is an extreme expression of shopping via what’s known in the business as “Discovery.” In social-media terms, it’s a bit like TikTok, which swaps the illusion of control created by follower-and-friend models for total submission to a top-down recommendation algorithm programmed to meet its users’ base desires, or at least to keep them occupied for a little while. If you can step out of Temu’s aggressive sales flow to browse more freely, the experience is not entirely unlike using TikTok in that it won’t be long before you see something you weren’t expecting, which then multiplies in front of you, manifesting seemingly infinite variations of itself. On TikTok, the objective is to keep you scrolling in hopes that you eventually encounter and interact with an ad; on Temu, everything in the feed is already an ad, and the goal is to convince you, after an extended period of bent-neck brain-dead scrolling, to actually buy something, anything, for just a few dollars.

This is all very novel to Temu’s many new American users, who, in in-app reviews and posts on social media, express uncertainty and ambivalence about what they’re seeing, at least until the products actually show up at their door, surpassing rock-bottom expectations with their mere presence. Anyone who has used Temu’s much larger cousin, Pinduoduo, a Chinese discount-shopping app where hundreds of millions of users buy not just assorted off-price goods but local fresh produce and groceries, will recognize elements of its interface. But they will also clock the American version’s somewhat weird and shabby inventory, which is still expanding but reflects the particular appetites of U.S. users who see it as a place to “shop like a billionaire” — which in practice means buying things you probably don’t need without worrying about how much they cost.

Users of Shein, the ultrabudget Chinese fast-fashion app, will also note some similarities in layout, pricing, and promotional strategy, although Temu will, again, feel more chaotic. Shein sources and designs much of its own clothing, giving it a great deal of control over what it sells (while making its dismal labor practices and material sources more visible). Temu, instead, relies on a sprawling network of merchants, many connected directly to factories, who sell through its platform. In the United States, Temu will feel most familiar to users of Wish, the last general-purpose direct-from-China retail app to break through. Wish topped the App Store charts back in 2018, on the back of a multi-hundred-million-dollar social-media advertising push, offering users extremely cheap products shipped directly from China with delivery times sometimes stretching over a month. The full story of Wish’s rise and fall is long and fascinating. The short version is simple enough: The novelty of ordering $0.79 toe spreaders from 8,000 miles away wore off; its products were often junk, even for the price; its customers didn’t stick around to see if things got better, which they didn’t.

Wish offers some warnings for Temu. Temu, however, is up to something a little different and operating in a changed environment. Wish grew out of an American ad-tech company and struggled to build real relationships with Chinese merchants. Temu shares a corporate parent with an established Chinese tech giant with deep connections to domestic manufacturers and an extensive logistics operation. Like ByteDance, which was able to spend lavishly launching TikTok in the U.S., PDD Holdings, which reported nearly $19 billion in revenue in 2022, can afford to shovel money into Temu. (Here is as good a place as any to try to situate Temu, which does not go out of its way to disclose its corporate parent, in the world: The brand is technically headquartered in Boston; its much larger sister platform, Pinduoduo, is based in China; both are owned by a parent company called PDD Holdings, which, according to SEC filings — it has been traded on the NASDAQ under PDD since 2018 — was headquartered in Shanghai until March of this year, when it suddenly began listing its jurisdiction of incorporation as … Ireland.)

Analysts at China Merchants Bank suggested in a February note that they expected Temu, which is regarded internally as a successful launch, to lose about $1.7 billion for its parent company in 2023. (According to estimates by YipitData, as of January, the month before the Super Bowl ad, Temu was on pace for $2 billion in annual sales, though almost certainly, that number is meaningfully higher now.) Those low prices, constant promotions, and generous affiliate commissions — TikTok influencers post screenshots of thousands of dollars of credits, and hundreds of dollars in actual cash, that they’ve been paid for signing up new users — actually are, in other words, a little too good to be true, at least in the long run.

While there’s plenty of garbage on Temu — as well as obvious knockoffs, including $12.98 Marc Jacobs totes, $5.99 Pit Viper sunglasses, and, almost charmingly, a knockoff of a $20 Casio digital watch — there are also products that will function as portrayed by the app. They arrive at least relatively quickly (usually within two weeks, but none of the shipments to my New York home have taken more than eight days). In fact, once you look past the novel interface and dismiss the various promotional interruptions, Temu, in structure and even in some product offerings, bears some resemblance to a much more familiar company playing in American e-commerce: Amazon.

In the years since Wish made its run at American shoppers, Amazon has undergone a subtle transformation of its own, relying more and more on third-party sellers based overseas, mostly in China. For Amazon, which charges those sellers for domestic warehousing, order fulfillment, and delivery, among other things, this was a pretty good deal. Over time, however, it has gradually altered the experience of using Amazon. Shipping is still fast and customer service is (for the most part) unmatched, but trusted brands have been gradually crowded out by numerous and often indistinguishable discount alternatives with nonsense names and nothing but Amazon’s own reviews to vouch for them. These products are often perfectly fine, of course, but have collectively given Amazon the feel of a massive off-price retailer. In the last five years, while Wish has become mostly irrelevant, Amazon has become a little bit more like Wish: a portal through which merchants in the manufacturing capital of the world can directly reach customers in the United States and elsewhere.

Temu inhabits the shrinking gap between the two. One of the most popular electronics items on Temu, for example, is a model of (usually) sub-$10 earbuds made by Lenovo, the tech conglomerate that absorbed IBM’s PC division in 2005. They’re no AirPods, but they’re about what you’d expect to get for $20 on Amazon, which is to say that they’re good enough for podcasts. (If you don’t like them, you can return them for a pair of similarly priced buds from Xiaomi, the second-largest smartphone manufacturer in the world behind Apple.) Like Amazon, Temu handles some logistics for sellers, which it also pressures with customer-focused return and support policies; unlike Amazon, which offers participating sellers Prime-speed shipping with a massive network of domestic warehouses, Temu has to hustle its packages across the world before passing them off to local delivery services including USPS. (This, of course, is the source of the mail-package carriers’ irritation: What’s with all the orange bags?) And while the shopping experiences on Temu and Amazon are quite different, they overlap plenty — on Prime Day, when Amazon is overtaken by random recommended deep-discount deals, it bears a resemblance to its newer competitors.

Juozas Kaziukėnas, who runs the research firm Marketplace Pulse, describes Temu as emblematic of a long-coming change in e-commerce. “‘Made in China’ cut out domestic manufacturing,” he writes. “‘Sold by China’ cut out domestic sellers. ‘Marketed by China’ is cutting out domestic retailers.” Some of America’s biggest retailers have outsourced core functions of their businesses. It helped make them rich. It might have also left them exposed.

There are plenty of ways that Temu could fail, leaving behind little more than a few million tons of polyester and dead lithium-ion batteries as its legacy. But underneath its churning surface, there’s evidence of something sturdier than Wish. Temu has pushed hard into fast fashion and reportedly tried to poach suppliers and employees from Shein in an effort to replicate the app’s breakout success, which means a lot of its offerings are nonstandard, short-lived, and effectively unique to the platform. But in categories I know most intimately — bike stuff and electronics — I found a number of brands I recognized, selling their products directly through Temu: one called Spotti and its sister brand Qualidyne, which sell exercise clothing and are owned by a company called Shenzhen Qualicos E-commerce Limited; a company called RockBros that makes cheap but serviceable cycling gear and accessories; and ARSUXEO, another budget apparel company.

These aren’t exactly household names even to people who care about this stuff. What they are are successful Amazon brands — companies that have thrived during the platform’s third-party-seller era. (In recent years, Amazon purged some major overseas sellers it accused of breaking the platform’s rules, most around reviews — Temu can offer some of them another chance at the U.S. market.)

I even found a few of the exact same products on Temu and Amazon. A jersey on Temu was listed for a few dollars less than Amazon’s $24.99 price but, with one of the almost constant promotional discounts, was attainable for less than half that. An extremely popular pair of Amazon earbuds cost a few bucks less on Temu, and both were sold by the manufacturer directly. Some well-reviewed bike pedals were $21.59 (that’s sans a $5 Earth Day discount that ran for a week) instead of $25.99; a clever little handlebar bag was $5.99 (or nearly free after a surprise discount before checkout) instead of Amazon’s version at $13.99, the former shipping in an estimated 8–12 days with a $5 credit for late delivery versus the latter’s, well, tomorrow with Prime.

Setting aside the possibility of government intervention — legislation designed to wound or ban TikTok would likely affect Temu, whose parent company has similar political liabilities and has been accused of mishandling user data — we find ourselves approaching some sort of logical endpoint for globalized e-commerce. The largest online retailer in the U.S. and one of the largest in China are now competing directly in apps installed on the same users’ phones, selling the exact same items produced by the same labor, differentiated by just a few days or a few dollars — buyer’s choice.