The rent is already too damn high and will soar even higher if political leaders can’t resolve a stalemate in the state capital that has slowed the creation of affordable housing in New York to a crawl.

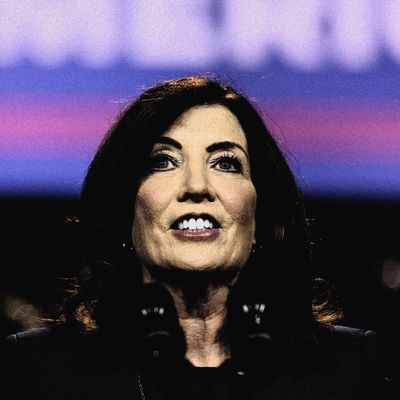

Governor Hochul has laid out an ambitious plan to build 800,000 units of housing statewide over the next decade; Mayor Adams has a similar “moon-shot” goal of building 500,000 units in the city during those same years. But both proposals face imminent danger of failure.

Progressive legislators are insisting that Hochul’s push for development be tied to a controversial measure called “good-cause eviction” that would cap automatic rent increases and make it significantly harder for landlords to kick out tenants. But Hochul and the leaders of the Assembly and State Senate — along with the state’s powerful real-estate lobby — are all opposed to the anti-eviction measure, which failed to pass the legislature in the past two sessions. An added complication comes from suburban legislators, who remain adamantly opposed to — and ended up defeating — a key provision in Hochul’s plan that would change or override local zoning rules that limit or prohibit the building of apartments in many parts of the state.

Hochul, Mayor Adams, and affordable-housing advocates say lawmakers in Albany should use the little remaining time in the current legislative session to find a compromise and spark a much-needed building boom.

“It’s important to not kick the can down the road. We can’t wait and say, ‘Let’s wait for another session.’ The urgency is now to build the pipeline,” Mayor Adams said at a recent housing rally in Brooklyn shortly after dispatching the city’s chief housing officer, Jessica Katz, and Deputy Mayor Maria Torres-Springer to Albany to make an in-person appeal to lawmakers. “We are all affected by this. There is not enough affordable housing for our families, our employees, our teachers.”

Adams faces housing challenges that include staffing shortages, zoning restrictions, and opposition to particular projects from City Council members. But his biggest obstacle is the ending of a state-tax program called 421-a that provided incentives for developers to build a mix of market-rate and subsidized apartments. The program subsidized more than 117,000 units in the city in the decade from 2010 to 2020, according to NYU’s Furman Center.

Admittedly, 421-a wasn’t a perfect program, which is why the legislature allowed it to lapse. As Comptroller Brad Lander has pointed out, 421-a provided more than $1.77 billion in tax breaks in fiscal-year 2022 alone, which critics called too rich of a subsidy to real-estate developers. And in some cases, depending on the particular project, the definition of “affordable” could be vague or misleading: Lander cited cases in which families earning as high as $139,000 a year for a family of three could get a subsidy and still pay $3,400 a month for a two-bedroom.

But no successor program has been created to replace 421-a, which is bad. Even worse is the fact that developers with 421-a projects in the works must get them completed by June 15, 2026, or risk losing the subsidy. Developers say they can’t meet the deadline and are asking state lawmakers to approve an extension so that current projects don’t lose the subsidy.

“There are dozens of projects that are at risk of stalling out,” Michelle de la Uz, executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit developer, told me. “Two-thousand of the 3,000 affordable units that are to be built as part of the Gowanus areawide rezoning are the ones that are really at risk.” Losing the state subsidy would leave many developers stuck mid-project.

“In my district alone, should we fail to extend the 421-a deadline extension, we are going to lose 3,000 units of deeply affordable apartments that are already in the pipeline,” State Senator Andrew Gounardes of Brooklyn said at an Albany news conference. “These are apartments for people making $50,000 and $60,000 a year, $70,000 a year — the missing middle in our housing market right now.”

But Housing Justice for All, the coalition fighting for the anti-eviction law, insisted that any fixes to 421-a be linked to stronger tenant protections. “Skyrocketing rents and evictions won’t be solved by wishing them away,” the group said in a statement. “They’ll be solved by doing the hard things: standing up to the real estate lobby and passing policies like Good Cause and rental assistance that have been proven to keep housing affordable.”

The coalition has the backing of politically potent allies, including the Working Families Party, the Democratic Socialists of America, and VOCAL-NY — and, crucially, the 53-member Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic & Asian Legislative Caucus.

“We need Albany to just act and do their job,” says Rachel Fee, president of the New York Housing Conference, a policy and advocacy coalition dedicated to affordable housing. Fee’s group has published a policy brief that suggests short-term fixes the lawmakers could implement while deferring a bigger deal involving 421-a and good-cause eviction.

A deadline extension should be granted to preserve the thousands of units currently at risk of losing their subsidy, Fee tells me, and the state should also reauthorize the J-51 property-tax exemption-and-abatement program, which expired this year. “That’s a preservation credit. This is getting owners to invest in their buildings and make repairs,” Fee says. “It just makes a lot of sense at this time. We have an increase in code violations. In the last two years, it’s gone up 54 percent. And over the next five years, we have nearly 60,000 units of affordable housing reaching the end of their regulatory agreements.”

Two other short-term boosts to New York’s housing stock are no-brainers: The legislature can and should authorize a regulatory process for converting office space to residential use — Fee estimates it could lead to 20,000 new apartments — and state lawmakers need to give the city the power to make basement apartments safe and legal.

Hochul has been urging members of the public to contact their legislators about the housing crunch. “Let’s get people demanding that their legislators be aggressive, deal with this, because otherwise we’re pricing New Yorkers out of their home state. And that’s not sustainable,” Governor Hochul told me last month.

The email address of every member of the Assembly is here, and you can find your state senator here. Please remind your representatives that New York’s need for affordable housing is an emergency that can’t wait. Even if lawmakers fall short in this legislative session, the issue needs to be front and center when they reconvene in Albany next year.