For decades now, major left-wing parties throughout the West have been bleeding support from the working-class voters whose interests they claim to represent.

In the mid-20th century, a voter’s socioeconomic position strongly predicted his or her partisan allegiance: In Britain, France, and the United States, voters with low incomes and only a high-school education tended to support left-of-center parties, while high-income, highly educated voters aligned with those of the right. In all three nations, this is no longer the case. All else equal, lower-income voters are still more likely to “vote blue” in the U.S. But that tendency is much weaker than in the past. Meanwhile, the relationship between educational attainment and partisan preference has flipped: Now, college-educated voters are more likely to support putative workers’ parties, while non-college-educated ones tend to favor conservatives.

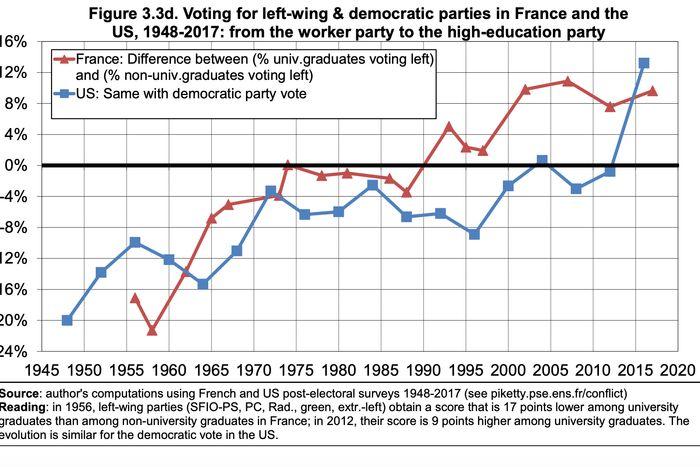

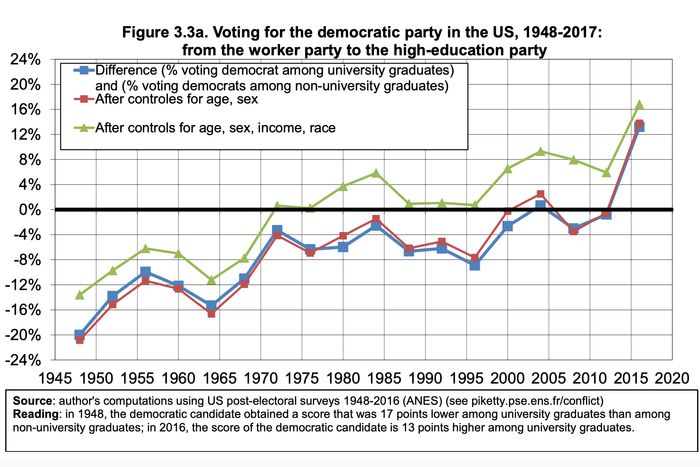

The French economist Thomas Piketty illustrated these trends in a 2018 paper:

The decline of class-based voting has long troubled the American left. And for good reason. Voters without four-year degrees are more numerous than those who have them, and America’s political institutions give the former disproportionate influence over election outcomes. For this reason, among others, the Republican Party has fared much better in the era of class depolarization than it did in the preceding one.

What’s more, the declining salience of class identity has exacerbated the challenge of enacting progressive reform even when Democrats do manage to secure power. Corporate America and the typical worker do not meet each other on an even political playing field. Effective civic engagement requires resources. It takes money to finance campaigns, time to monitor legislative and regulatory developments, and organization to bend those developments in one’s favor. The Chamber of Commerce can shoulder these costs much more easily than isolated working people. Traditionally, the left’s formula for overcoming this fundamental disadvantage has been to (1) help workers collectivize the costs of political engagement by organizing into trade unions, and (2) exploit the working class’s numerical supremacy to overwhelm capitalist opposition. Or, as socialist sloganeers have summarized it: They’ve got money, but we’ve got people; we are many, they are few.

But once workers stop organizing into unions, and stop voting on the basis of class identity, they cease to be “many” in the operative sense. Both major parties become intra-class coalitions in which working people’s interests as workers are either balanced against those of corporate coalition partners (as in the Democratic Party) or ignored (as in the GOP). Meanwhile, absent the concentration of working people into one dominant partisan coalition, America’s veto-point-laden legislative institutions — and the tendency of staggered presidential and midterm elections to produce divided government — render large-scale reform of any kind a Herculean task.

Put all these considerations together, and it seems less than coincidental that the decline of class-based voting in the U.S. (and Britain and France) has corresponded with an upsurge in income and wealth inequality.

So, the left is right to lament class depolarization. But some left-wing accounts of how this development came about, what implications it has for contemporary electoral politics, and how the working class can be “brought home” are less convincing.

It’s time for some “Marxist electoral theory.”

One prominent left-wing account of how the era of class politics was lost goes (very roughly) like this: In response to Nixon and the stagflation crisis — and then, even more vigorously, in the wake of Ronald Reagan’s election — the Democratic Party decided it needed a new agenda that would better appeal to professional-class voters in suburbia and big-dollar donors on Wall Street. In practice, this meant trading in the party’s New Deal–era veneration of organized labor and welfarism for a meritocratic liberalism that promised “equality of opportunity” (in the limited sense of abolishing discrimination against individuals on the basis of identity), while condoning gross inequalities of outcome. Although these shifts may have been rationalized as a reaction to working-class defections from Blue America, it really served to catalyze those defections. As both parties camouflaged their mutual complicity in middle-class decline by leaning into “culture war” conflicts, many workers gave up on politics and dropped out of the electorate — while some white workers yielded to the siren song of the GOP’s reactionary populism. All of this produced a self-reinforcing cycle — the more dependent Democrats became on college-educated voters, the less willing the party was to embrace a social-democratic message robust enough to repoliticize disaffected workers, and repolarize the electorate along class lines.

Not everyone on the left subscribes to this general narrative (personally, I think it has its insights and omissions). And many who do subscribe to it will surely quibble with my summary. But for our present purposes, the fine details of this history are of less relevance than two conclusions that some leftists have derived from it: First, that Democrats can dramatically increase their share of non-college-educated voters by campaigning on more robustly populist messaging and policies, and second, that the Democrats’ highly educated and/or suburban wing is a force for moderation within the party that must be overcome.

The 2020 primary — and Joe Biden’s triumph therein — has sparked a vigorous intra-left debate over these premises. For progressives partial to Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders’s failure to rouse working-class nonvoters from their apathy — or retain his white working-class support from 2016 — demonstrated the bankruptcy of “Marxist electoral theory”: Professional-class Democrats aren’t holding back the progressive movement, leftists who refuse to seek common cause with such Democrats (out of a baseless conviction that there is a slumbering proto-socialist proletariat whose imminent awakening will free them from the indignities of coalition-building) are. For some Sanders vanguardists, meanwhile, Warren’s underachieving campaign — and failure to keep most college-educated Democrats from rallying behind one moderate or another — proved that the left’s path to power cannot run through the suburbs.

In my view, some Warrenites can be too sanguine about the challenges that class depolarization pose for social-democratic reform (and their confidence that Warren was a better vehicle for progressives than Sanders in the 2020 primary seems unwarranted in retrospect). But their broad premises about electoral politics are closer to the truth.

What’s the matter with class reductionism?

The problems with the hypothesis that Bernie Sanders could rapidly remake the class composition of the Democratic coalition through the sheer force of his socialism were twofold: First, in the absence of institutions that cultivate class consciousness and solidarity, occupational status exerts only a very limited influence on voters’ views, even on questions of economic policy. Second, although educational attainment does serve as a rough proxy for class position, it also exerts its own independent influence on voter ideology.

The evidence for these claims extends well beyond the fate of Sanders’s primary campaign. Some socialist commentators have argued that the primary’s outcome did little to discredit the “political revolution” theory of electoral change. As Nathan Robinson of Current Affairs writes:

[T]he whole theory the left had was not that the primary was easy to win, but that we would win the general election, because we would be given an opportunity to court independents and the politically disaffected — the kind of people who do not vote in party primaries … We know that it’s hard for a socialist to win the Democratic primary; the open question is whether a leftist Democratic nominee would prove an effective antidote to Trump.

I agree with Robinson that how Sanders would perform against Trump in a general election is an open question. And I also think there is reason to believe that the Vermont senator had unique appeal with a certain subcategory of non-college-educated voter, and that this appeal may have made his general-election coalition marginally more working class than Joe Biden’s. But Robinson’s suggestion that Sanders’s message has less appeal among working-class Democratic primary voters than it does among working-class swing voters (or registered nonvoters) is dubious.

Bernie Sanders has had a national platform for four years now. He is one of the most well-known politicians in the country, and his signature proposals are fixtures of public debate. And in polls of the general electorate, Sanders performs about as poorly with non-college-educated white voters as any other Democrat. In a recent survey from Quinnipiac University, such voters disapproved of Sanders by a 56 to 30 percent margin, which was two points worse than Biden’s showing with that same demographic. By contrast, a recent survey from Grinnell College found that “suburban women” approve of the democratic socialist by a margin of 54 to 32 percent. In fact, in virtually every survey of registered voters, college-educated whites evince more sympathy for Sanders than non-college-educated ones (since nonwhite voters lean heavily Democratic regardless of class or education, the debate over whether the class basis of the Democratic coalition can be changed has centered on divisions within the white electorate).

The fact that Sanders boasts more support among suburban college graduates than whites with low levels of education shouldn’t be surprising. His agenda may have more to offer the latter in material terms. But in the contemporary U.S., college-educated whites tend to evince more progressive policy preferences than non-college-educated ones even on matters of redistribution. In a national survey fielded earlier this month, the progressive think tank Data for Progress asked voters, “Do you think it is the responsibility of the federal government to see to it that everyone has health-care coverage?” College-educated white voters said “yes” by a margin of 50 to 39 percent; among non-college-educated white voters, that margin was 43 to 39 percent.

The results of Maine’s 2017 referendum on Medicaid expansion lend credence to this finding. Given the opportunity to expand the availability of socialized health insurance, the most highly educated parts of the Pine Tree State voted in favor, while the least well-educated regions voted against. Material interests weren’t entirely irrelevant to voting patterns: Researchers found that, if one held education constant, then areas with higher incomes were more likely to oppose Medicaid expansion. But an area’s median income was still a less reliable predictor of its support for the policy than its average level of educational attainment; college trumped class.

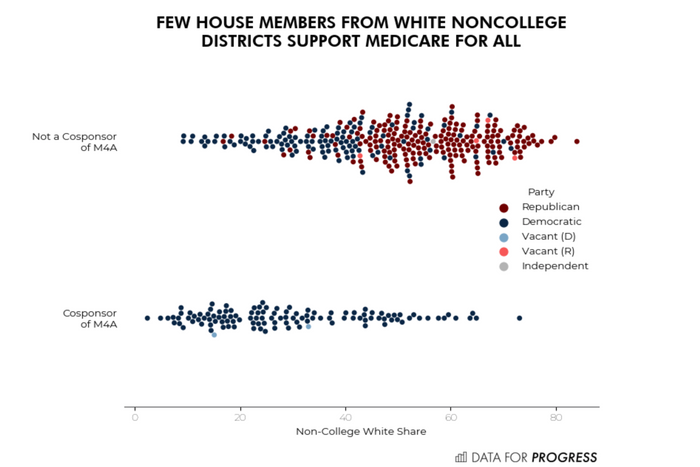

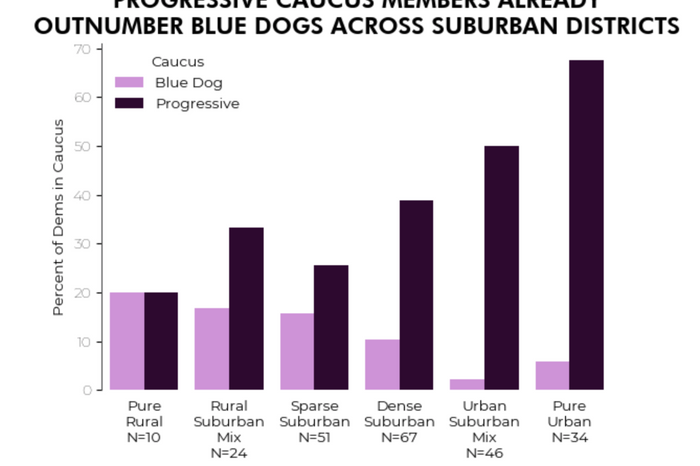

This same dynamic is reflected in the ideological tendencies of the Democratic Party’s congressional caucus. Democratic House members who represent districts with above-median levels of college-educated white voters are more likely to belong to the Progressive Caucus — and to co-sponsor Medicare for All — than those who represent districts with above-median levels of non-college-educated white voters.

Democratic senator Joe Manchin represents a state whose median income is $45,000 a year. He is among the most conservative Democrats on Capitol Hill, and said in 2019 that he would not vote for Bernie Sanders in a race against Donald Trump. Manchin’s House colleague, Ro Khana, represents a constituency whose median income is $141,000. Khana is among the most left-wing members of Nancy Pelosi’s caucus and co-chaired Bernie Sanders’s campaign. This is difficult to explain if one posits a tight correspondence between an area’s class composition and its appetite for social democracy. But it’s much less mysterious if one presumes a correlation between high levels of education and support for progressive politics: 60 percent of the adults in Khana’s House district are college graduates, while just 20 percent of those in Manchin’s West Virginia boast bachelor’s degrees.

Colleges really are vehicles for left-wing indoctrination.

Which raises the question: Why does college attainment have such a paradoxical influence on white Americans’ politics?

A generation ago, college graduates were a Republican constituency. And the material basis for that affinity remains sound. There is a reason that political scientists use educational attainment as a proxy for class: The college wage premium is large. To be sure, there is a large and growing number of economically precarious college graduates in the United States, and this surely explains part of the demographic’s leftward drift. Similarly, some non-college-educated voters are petty bourgeois business owners. And high-income, low-education Americans are indeed the most reliably reactionary voting bloc in the country. But car-dealership tyrants are exceptional; the typical non-college-educated Republican voter is a worker, not a capitalist. While highly imperfect, educational attainment does still bifurcate the middle and working classes reasonably well.

So why did the political significance of college attainment flip over the past four decades?

A 1979 study published in the American Journal of Sociology offers one compelling explanation.

Ironically, the paradox that this paper intended to resolve was the exact opposite of the one that befuddles the left today. To the political scientists Terry S. Weiner and Bruce Eckland, the tendency of college graduates to vote Republican in the 1970s was counterintuitive. After all, they wrote:

[T]he theory that colleges and universities function as important socializing agents in the development of a tolerance for ambiguity and a belief in civil liberties and equality would not normally lead one to hypothesize a positive correlation between educational attainment and identification with the “conservative” Republican Party …

There is considerable evidence that college generally does liberalize attitudes … This appears to be true on most measures of political liberalism, such as tolerance for ambiguity, openness to change, a belief in equality, and humanitarian attitudes.

Weiner and Eckland set out to reconcile these findings with well-established voting patterns. They reasoned that the correlation between college attendance and GOP-voting might disappear if one accounted for other confounding variables. For example, the children of the upper-middle class were more likely to attend college, and the upper-middle class was a Republican-leaning constituency. Given that partisan allegiances are partly heritable, the overrepresentation of Republicans in universities’ freshman classes could be sufficient to explain why most college graduates voted Republican — even if, all else equal, the experience of attending college made Americans more liberal. Similarly, they hypothesized that the higher socioeconomic status of college graduates, relative to the less credentialed, could also be obscuring the independent influence of higher education on political attitudes.

To test these hypotheses, the researchers examined two sets of data: a 1955 survey of high-school sophomores conducted by the Educational Testing Service, and a follow-up survey with those same Americans taken by the University of North Carolina in 1970 (since the South was still governed by one-party rule in this era, Eckland and Weiner limited their analysis to northern respondents). These questionnaires provided the respondents’ partisan affiliations as teenagers and as adults, their levels of educational attainment, their occupational statuses, and their parents’ partisan preferences.

As expected, the sophomores who went on to attend college were more Republican than those who did not. But once Eckland and Weiner controlled for parental partisanship, this correlation vanished: Among respondents with the same familial partisanship (or nonpartisanship), college graduates were more likely to support Democrats in 1970.

To the researchers’ surprise, occupational status and income had relatively little influence on the respondents’ voting behavior. Controlling for parental partisanship, higher-earning respondents were only marginally more Republican than lower-earning ones. Which is to say: The survey data suggested that college graduates’ tendency to support Republicans was already — in 1970 — primarily a vestige of a bygone era when class still dominated political behavior.

Partisan preferences are only partly heritable. You are more likely to vote the same as your father than to vote the same as your grandfather. Thus, if class-based voting among young people in the 1970s was largely an artifact of which side their parents took on FDR, then one would expect class-based voting to decline almost mechanically with each ensuing generation — unless some emergent circumstance restored class identity to its 1930s level of primacy in U.S. politics.

But Eckland and Weiner believed that novel circumstances were more likely to hasten the erosion of class-based voting. All else equal, going to college made Americans more left wing, especially (though not exclusively) on questions of morality and cultural identity. And since a growing number of Americans, from a diversifying array of socioeconomic backgrounds, were poised to attend college in the coming decades, education-based political divisions were likely to grow in salience over time, while class-based ones diminished. As the researchers wrote:

Between 1940 and 1960 the proportion of all 18-21 year-olds enrolled in college more than doubled. Even if this trend does not continue and the figures stabilize, the average educational level of the adult population nevertheless will continue to rise for at least the next 4 or 5 decades, just as it has for the past several decades. This opens up the possibility that higher education is strongly implicated in the decline of class politics.

Four decades later, that “possibility” has grown to resemble a proven fact.

The left has good reason to lament the decline of class politics. Class-based political organizations were the muscle behind virtually every major progressive reform in U.S. history. And a radicalized working class is a much more plausible agent for democratizing capital ownership than are affluent liberals (however comfortable the latter may be with western European–style social democracy). More mundanely, unless the Democratic Party staunches its bleeding with non-college-educated voters, it will struggle to assemble Senate majorities.

But in the absence of a strong trade-union movement or laborite media, class position exerts a much weaker influence on voting behavior and policy preferences than some socialists have assumed — while higher education exerts a much stronger one. Some of America’s most ardent dialectical materialists are themselves affluent college graduates whose politics grew more radical during their time at university. If academic socialization could teach such children of the upper-middle class to prioritize Marxist convictions above their 401(k)s, why couldn’t it also teach millions of “normie” college-educated Democrats to prize progressive principles above their marginal tax rates?

None of this is to say that leftists shouldn’t be fighting for the hearts and minds of white high-school graduates. Class position does not mechanically determine ideology. But neither does race or education. Tens of millions of white non-college-educated voters cast their ballots for Democrats every election year, and the party could not survive without their support. There is no inherent reason why a larger percentage of this demographic group can’t be won over to progressive politics. But there’s little evidence that mere advocacy for social-democratic reform will overwhelm the contingent reasons for the prevalence of white working-class conservatism and/or nonvoting. Only left-wing institutions with a footprint in non-college-educated voters’ workplaces and communities can plausibly overwhelm the hegemony that right-wing media exercises over the median white American’s political imagination. Whatever flaws the left’s account of class depolarization may have, its critique of the Democratic Party’s malign indifference to organized labor’s fate is unimpeachable. The failure of every unified Democratic government since the Second World War to prioritize labor-law reform doubtlessly exacerbated the rightward drift of the white working class.

Nevertheless, for the purposes of near-term electoral strategy, the left must presume that the class composition of the Democratic coalition cannot be drastically changed in the course of a single campaign — and that college-educated Democrats are as “natural” a constituency for the party’s progressive wing as any other.