When virologist Jeremy Kamil got a look at the Omicron sequence posted to GISAID — an open-source website and global nonprofit that helps scientists share genome sequencing — shortly after the new variant was identified last week, it shocked him. Kamil, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, co-authored a study in February identifying seven lineages of the virus that cause COVID-19. He did so by analyzing changes to the virus’s spike protein: the macelike, studded surface of the coronavirus. Intelligencer asked Kamil what it is about Omicron that has virologists gobsmacked and why public-health officials are so concerned.

What was your reaction when you saw the Omicron sequence?

I was just totally shocked. It was like coming home to your front lawn after vacation and someone hasn’t just planted a couple of flowers in the flower bed — they’ve totally remodeled everything. It was a tectonic shift in the antigenic landscape.

How does Omicron compare with other variants you’ve seen over the past year?

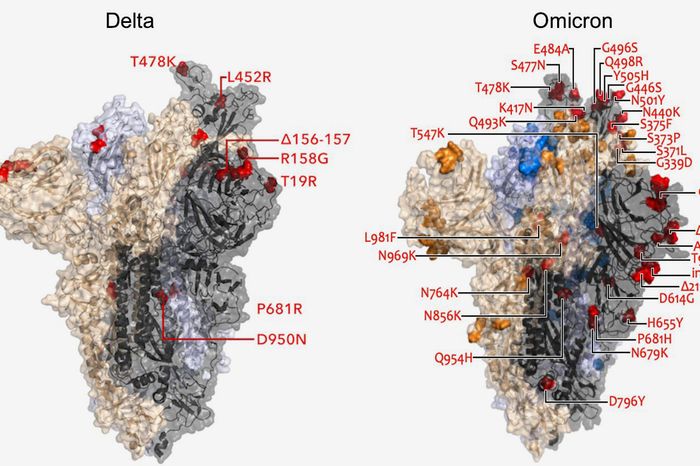

This variant has a whole slew of mutations far beyond what has been observed in any other variant we’ve seen. Depending on how you define the receptor-binding domain, there are somewhere between ten and 15 mutations just in the receptor-binding domain alone, which is just outstanding. I think Alpha had something like eight mutations across the spike, and this has over 30 across the spike. So it has a whole lot of changes going on, and that’s a lot of the reason people are concerned. The immune response has been trained against the ancestral spike present in the vaccines, or, if you’ve been infected, your immune response is trained against whatever variant you were infected by, which would be Delta for a lot of people. The only modest silver lining is that Omicron has at least a couple of changes in common with Delta. If someone did develop antibodies from a Delta breakthrough infection or a Delta infection, they may have some cross-protection against Omicron.

How long are we talking about until we know how protected we are?

Public-health authorities are telling us about two weeks. That sounds somewhat realistic because people are basically going to have to print synthetic DNA. What they do first is use these things called pseudo-viruses. They’ll take something called a lentiviral vector, and they’ll use the spike protein of Omicron to pseudotype it so it uses Omicron’s entry machinery instead of the natural HIV entry machinery. They’ll test serum from people who’ve been vaccinated or who have recovered from coronavirus disease, and they’ll look and see how well that neutralizes.

It’s a very valuable experiment to do even though it can be a little bit crude. The best experiments will be with actual Omicron-variant coronavirus. But that has to be grown up, and at biosafety-level-three labs, it’s harder to do that work because there are more precautions and less lab space. Pseudotype experiments can happen at biosafety-level two, which is what most research labs in the U.S. are.

So how concerned should we be about breakthrough infections at this point?

Due to how extensively mutated the spike gene is in this variant, there’s good reason to be concerned about breakthrough infections. We already saw a lot of breakthrough infections with Delta, and you’d expect this critter to be more evasive than Delta. The good news for Delta was that even if there were breakthroughs, we knew that the severity of the infection was usually far less in people who were vaccinated. The reason people are more concerned with Omicron is that we don’t know what the disease is going to look like even in vaccinated people.

I do think there are reasons to be optimistic. Some people are saying, “Hey, we’re back at square one.” That’s not really true. We have mRNA-vaccine platforms. We know that masking works. If you go back to March 2020, there was so much unknown. We were locking down playgrounds. We’re not back there. I think it’s just a sobering moment in which we have to remind ourselves that we’ve never moved through a pandemic of a coronavirus before. There’s nothing certain in human history about this. We know from seasonal coronaviruses that those probably started out as pandemics, but we don’t know for sure what it was like to live through one of those. We don’t know how many waves to expect. There are more human beings on the planet now than there ever were before, which means there are more potential hosts to drive rapid evolution of this virus.

A South African doctor, who was one of the early doctors to suspect a new variant, has described symptoms in patients as “very mild.” Is that anecdotal evidence worth much at this point?

I saw someone tweeted that. I even quote-tweeted it and said something snarky like, “Huge, if true,” but then I took it down because people didn’t realize I wasn’t being serious. It’s way too early to know. These cases, when they emerged in South Africa, they may have been people who had already survived a Beta infection, for instance. Or they may be younger. You don’t know from such small numbers. It would be great if it happens to be true that symptoms are mild.

If you talk to corona virologists, who are the real experts, they’ll tell you a lot of the biology comes down to the spike protein, and this spike is different enough from the ancestral spike that it’s not implausible that the disease characteristics might be different. However, I’d say that the safest thing to do is to presume for the time being that this is identical to Delta or Beta or Gamma or the ancestral Wuhan virus in terms of the danger of being infected by it. It’s something to be concerned about. It’s safe to presume that this is just as bad as getting the virus in 2019 until we have proof otherwise. We shouldn’t panic, but we should be careful. I wouldn’t go to a karaoke lounge right now or even a crowded bar.

Are you on the lookout in your own lab?

Our university center set up a giant testing center and sequencing lab, and of course we’re going to keep our eyes peeled for it. So far, there’s been nothing detected in the United States. It’s probably already here; it just hasn’t been seen. It’s probably going to be at least a 72-to-96-hour turnaround from a swab to a sequencing result, and from what I understand, our country does a much poorer job than a lot of other countries testing people who come in from airline travel and whatnot. We may not detect it as quickly as possible. I’m also concerned that a lot of people have pandemic burnout, and rightly so. I think a lot of people who get mild infections aren’t going to want to necessarily get a coronavirus test. There’s so much political polarization and misinformation. You have a good segment of the population who are burned-out and another segment of the population who don’t even believe in science. Neither of those segments of people are going to show up at a testing center if they have a mild disease. That’s a real risk for us going forward.

As we continue to make our way through a coronavirus pandemic, what kind of progress has been made, in terms of systems and processes, to identify variants?

That’s a really great thing that you asked. It’s really important that reporters mention GISAID because they have been heroic in setting up a way of sharing genetic information that removes the hesitation that scientists usually have about putting their data out right away in a public-health emergency. Scientists live by publications and grants, and there’s a huge disincentive to putting your data out in the public domain. Imagine walking around New Orleans with a microphone and telling a jazz musician that once you record them, you can do anything you want with their music. You’d have no jazz music recorded ever. GISAID was rolled out in 2008 with the idea that scientists like to have their name out there when they release something. GISAID enforces those terms. They allow anyone to see the data, but you have to register and agree to those terms, almost like a driver’s license.

With Delta, it spread for a while before we realized it, and I got the impression that maybe India sat on the data a little bit longer because they weren’t being compensated for it. The scientists, or government, were probably more bureaucratic about how and when they could share data. They released it when they felt like it was the right time to release it, but not necessarily as quickly as they could have. We didn’t have the warning that we might have had otherwise about Delta. Whereas with Omicron, we have a great head start. That’s why we have to thank Botswana, South Africa, and Hong Kong for sharing that data right away. There was no lag.

More on omicron

- What to Know About the New COVID Booster Shots

- The Dismantling of Hong Kong

- What We Know About All the Omicron Subvariants, Including BA.2.12.1