This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Henry Williams was 7 in 2008, and what he remembers about 2008 is that his dad lost his job. Henry’s suburban childhood was comfortable, but even so, it was shadowed by an awareness of precarity. For a time when Henry was growing up, an aunt in her 20s lived with his family while she was between jobs. The aunt had gotten an M.F.A. in film. In the years to come, an M.F.A. in film would seem like a bad plan to Henry.

When Henry Williams arrived at college, he was a STEM guy: Computers were what you did to be practical. Eventually, he imagined, he might get a Ph.D. in physics. But his undergraduate career at Columbia was still young when other events intervened. Freshman year, he and a friend started a not-quite-kidding presidential campaign for former Alaska senator Mike Gravel. (They had heard about the senator on the socialist comedy podcast Chapo Trap House.) The campaign consisted primarily of a vigorous presence on dirtbag-left Twitter, where the so-called Gravel Teens gave their 89-year-old candidate’s account an unlikely fluency. The campaign did not achieve its goal of sending Gravel to the Democratic-primary debates, though it did attract mystified attention and national press. Williams’s allegiance passed in due course to Bernie Sanders, whose campaign suffered irretrievable defeat just before COVID shut down Williams’s campus. Dissatisfied with remote school and disillusioned with college in general, he decided to take a year off — from class, but not from learning.

What he wanted, he told me, was to find someone who could explain “what the hell was going on in the world.” From Sanders’s loss, to the emergence of a global pandemic, to the economic fallout, “it’s this incredibly fast-moving maelstrom of events, and particularly if you talk about the economics of it, it’s almost impossible to get a grip on.” This was when Williams discovered the work of economic historian Adam Tooze.

In the corner of Twitter where Williams dwelled, Tooze had emerged as the explainer of first resort. He was the guy other guys recommended; he was also, from what Williams recalls, tweeting “a hell of a lot.” Williams heard Tooze on the Bloomberg Odd Lots podcast explaining how the current crisis was and wasn’t like 2008. He read Tooze in the London Review of Books explaining the pandemic’s effects across China, the U.S., and the eurozone. Starting with The Deluge, Tooze’s 2014 account of World War I and its aftermath, Williams proceeded to read all of his books — The Wages of Destruction (about the Nazi economy), Crashed (about the 2008 financial crisis), and Statistics and the German State, 1900–1945 (self-explanatory). His year off from college became, in effect, an independent study in Tooze.

In seminar rooms and on Twitter, Tooze has won a following: They are primarily young men, known sometimes as “Tooze Bros” or “Tooze Boys,” if boys can encompass a male population in its early 20s to late 30s. Like Williams, these fans tend toward the left and have occupations that enable them to spend hours on Twitter forming opinions. They concern themselves with American economic and foreign policy, with special attention to the fraught places where these two intersect — for example, in confronting climate change. Perhaps some would once have cast their critique in the shitpost mode of the Chapo heyday, but lately, in place of provocation, they prefer an avalanche of facts. The Gravel campaign, Williams reflected, “feels like forever ago. I feel a lot older than I was then.”

What Tooze gives a reader like Williams is not a piercing, singular insight but a sense of rigorous mastery. In March, drawing on work by scientists, work by economists, and context in German politics, he assessed the feasibility of a Russian-energy boycott by Germany. (Conclusion: certainly difficult but perhaps not impossible.) Tooze’s great intellectual power is a gift for synthesis. “He just digests staggering amounts of information,” said Ted Fertik, one of his former Ph.D. students and now a policy strategist. Tooze roves across vast fields of data — historical data, technical data, data about Russian currency reserves, data about the Nazi steel-tube industry — and returns with a reasonably accessible brief in hand. His omnivorously quantitative approach combines with his economic expertise to reveal familiar subjects in new ways. In Crashed, the book that was many readers’ introduction to his work, the financial crisis of 2008 becomes something even more complex and catastrophic than it might initially have appeared: an American housing bubble, yes, but also an international decade-long disaster brewed by the global dollar system.

As a historian, Tooze once observed that work drawing on quantitative sources had become “a minority interest” in the field, one greeted at times with “an attitude of hostility and incomprehension.” As a public intellectual, he has found a more receptive readership. Let the historians wring their hands about Foucault and power; off campus, numbers make you sound like you know what you’re talking about.

In the years since the financial crisis, a growing audience has sought answers regarding capitalism’s failures. Tooze, with his close study of what technocratic elites and free-market ideology have wrought, offered ammunition for leftist critique. As with the economist Thomas Piketty a few years prior, this has made him an unlikely celebrity. Crashed depicted the sheer scale of government intervention required to prop up global finance, and all the ways that falling short — doing too little or doing it too late — had led to needless suffering. To challenge decades of economic orthodoxy urging government thrift and free markets, it helps to have someone with the data to back up John Maynard Keynes’s assertion that “anything we can actually do, we can afford.” A figure like Sanders could make the case that things had to change, but a figure like Tooze could provide the proof.

Tooze’s ongoing study of past global disasters has arrived at a present rife with global disasters to explain. The events of spring 2020 vaulted him to prominence: As much of the world shut down, his schedule filled. On one occasion, when booked back-to-back, he left a Zoom panel with Emmanuel Macron while the French president was mid-sentence — just closed the window on Macron. In an email, Tooze recalled, “I was kinda in shock for days afterward ;).”

Tooze’s office at Columbia is approximately the height of two offices vertically stacked. Bookshelves run floor to ceiling along three of the walls, and on the fourth, beside a window open to the traffic noise of Morningside Heights, hang two oil paintings of airplanes. These were the first oil paintings Tooze bought, back when he was in graduate school. Originally commissioned for Shell’s London corporate headquarters, they capture technological optimism at a 20th-century peak — “Supersonic long-distance passenger travel as it was imagined in the early ’60s,” Tooze said, “with a little bit of a sci-fi turn thrown in.”

Although Tooze’s family is British, he spent much of his childhood in Germany, where his father worked as a molecular biologist. Growing up in the southwestern part of the country was, in Tooze’s telling, akin to growing up in a combination of Silicon Valley and Detroit — Mercedes and Porsche were both nearby. An early ambition of his was to become an engine and chassis designer for race cars. “I was quite serious about it,” he told me when we spoke in his office on a February afternoon. “I was doing, for that age” — early teens — “quite sophisticated calculations shaping the exhaust pulse as it exits the combustion chamber so as to minimize ‘back pressure’ and maximize scavenging and all that.” This was one of two great intellectual infatuations Tooze nurtured in his youth; the other was military history. “I’ve sort of sublimated those into more mature interests,” he said.

His fascination with the inner workings of complicated machines now attaches to such subjects as the global bond market. Not unlike a Porsche engine, it is a product of material constraints and countless decisions made by highly trained experts. And these experts — the people drawing up plans and issuing orders — stand at the center of his work. Just as traditional military history offers a top-down perspective, so too does the Tooze view depict a world of high-level strategy: A move like Mario Draghi’s 2012 declaration that the European Central Bank, of which he was then president, would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro is equivalent to a decisive cavalry charge.

Tooze’s parents had met at Cambridge, where his father was a scholarship student and his mother, he says, a child of the “Brahmanical upper-middle class.” Tooze, upon applying, was torn between studying economics and history. Because British undergraduate education involves a single focus, this choice appeared absolute. In economics, Tooze was by his own account “kind of on fire” — he’d been permitted as a teenager to teach a class on Keynesian models at his secondary school. His prospects in history appeared less auspicious; he enrolled in economics. With its entrenched traditions and exacting, unquestionable standards, the Cambridge approach to pedagogy makes intellectual life a kind of specialized craftsmanship. Tooze compares it to “being an Italian artisan in a very demanding trade like sausage-making or Parmesan-making or violin-making.” He chafed at the curriculum.

After getting his history Ph.D. at the London School of Economics and returning to Cambridge as an assistant professor, “I found it very confining. It made me depressed,” he said. His “lifeboat” in those years took the form of a course he devised on the end of history. Reading the venerable Marxist Perry Anderson on Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man had been a “life-changing” experience for Tooze — where many on the left saw a celebration of liberal capitalism’s triumph, Anderson saw a historical analysis worth serious scrutiny. Tooze took Anderson’s approach as inspiration for the class, and it proved “the first time I kind of got a sense of what liberated, intellectually creative teaching could be like at grad school,” he said. “And then that’s what I did at Yale.”

Arriving in New Haven in 2009, he found himself part of a new academic economy. Within the artisanal guild system of Cambridge, “if you’re the salami-maker, that’s what you do.” At Yale, by contrast, “you’re being hired as a senior partner to a small academic consultancy and teaching business with a very large capital base. And so what they’re interested in doing is maximizing your human resource.” Tooze spoke fluent German, so he could teach alongside the Germanists; he knew his military history, so he could join John Lewis Gaddis’s Grand Strategy program and “do the whole Kissinger thing.” He’d found a polymath’s paradise and, in his view, the style that would make his career. The interdisciplinary approach Yale encouraged is “why I’ve ended up with you interviewing me,” he said.

At Yale, he became interested in the financial crisis of 2008 as history — how its story was told even as events progressed. He soon saw that in order to understand the crisis as history, he would have to understand the crisis itself. “I realized it was a transatlantic story, like the story I told in Deluge and in Wages of Destruction,” Tooze said. “You had to relate European and American history, in this case, by way of their banks. The other thing I realized was that we were living through — as a result of globalization and financialization — a quite fundamental challenge to the framework of macroeconomics as we understood it.” Conventional macroeconomic models had failed to predict the crash, “and not by accident. The reason they had failed to predict it was the way they were built.” The lecture course that Tooze first taught in 2013 drew on economics, politics, and history. It also drew on Tooze’s particular charisma as a lecturer — his ability to convey a gobsmacked awe at the facts as well as the facts themselves. Attracting a mix of econ majors interested in being bankers and lefties interested in bankers’ failures, it became the kind of class where students showed up early to get a good seat. Crashed, essentially a book-length expansion of the course, was published in 2018.

Yale was also where Tooze began offering a graduate course on the philosophy of history. Fertik remembered Tooze’s role in the class as a “convener” more than an instructor: someone who was “surely in the top half of the group in terms of the depth of his existing knowledge of the texts,” but who acknowledged that some of the students had expertise surpassing his own. He came to the material with a sense of discovery. In 2011, when Fertik took the class, it unfolded alongside Occupy. While he and his classmates wrestled with ideas about the end of history, a few hours away, history seemed to be taking place. “I reacted to Occupy as indicating the possibility of an ‘end to the end of history,’ ” Fertik wrote in an email. “This only intensified the feeling that the texts we were reading had visceral stakes.” Recalled Tooze, “A bunch of my more radical students were doing Occupy part time and this course. A whole bunch of them were actually off their heads on pills, and I was off my head from just not sleeping.” He was struggling with writing The Deluge at the time. “And it created this intense — I mean, it was amazing. An incredible classroom dynamic.” The group sometimes gathers for reunions. “You can die happy after having that teaching experience once in your life,” he said.

The students who collected around the class and the reading group it spawned came from many disciplines: philosophy, history, political science. They were also predominantly male. Regarding the gender dynamic of the scene, “I worry about it,” Tooze said, “because there’s a way of interpreting it as exclusive. And that’s very delicate terrain. It makes me very thoughtful, really, because it isn’t true statistically that I don’t have any female students and haven’t worked closely with women.” Within the Tooze Boy milieu, “it’s a homosocial environment, and that’s easy. We know it’s easy. It’s also true for women,” he said. “It creates a kind of bond, there’s no question.” He is relieved that his current Columbia reading group has a roughly 50-50 gender split. Nevertheless, “there is this Tooze Boy thing, and they are boys,” he said.

When Henry Williams returned to school last fall, he saw that Tooze, who had moved from Yale to Columbia in 2015, was teaching a seminar called “Capitalism and Democracy.” The class was a graduate offering — technically, Williams was not qualified. When he showed up on the first day, “I selectively omitted the truth,” he said. Tooze’s eventual verdict was that as long as he kept up, he could stay. The next semester, Williams joined a Tooze-led reading group on the political economy of climate change. “The hope of this group is to be sort of generative,” Williams told me. “Breaking new ground, reaching new terrain.”

In February, on the night I sat in, the group was discussing the book Bolivia in the Age of Gas. “I’m finding this stuff very challenging,” Tooze told the group. “I’m finding it very unfamiliar and outside my comfort zone.” The discussion that followed alighted on thinkers from Max Weber to Andreas Malm. When listening very closely, Tooze bowed his head and shut his eyes. Williams ventured that the book undersold Evo Morales as a political figure. “All that is brilliant and right,” Tooze told him. Williams suggested that the extractive masculinist order in Bolivia resembled that of West Virginia. Tooze nodded forcefully — or Britain or Poland, he added. Later, Williams brought up meeting a person with a venture-capital-funded space-mining program, and there was laughter all around. Before Williams introduced himself to me after class, I had indicated him in my notes as “loud boy.”

Within the academy, Tooze embodied a certain graduate student’s fantasy: a scholar defying recent trends toward social and domestic history, focusing instead on the elites who dominated economic and political battlefields. When Yakov Feygin, now an economic-policy researcher at the Berggruen Institute, was getting his history Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, “I would joke that I want to be Adam Tooze when I grow up,” he told me. (He’s now at work on a book he describes as something like “Wages of Destruction for the postwar Soviet economy.”) Between Tooze and his students, the influence ran both ways. Those with whom Tooze worked most closely would read his publications in progress, inform his thinking, push him not to equivocate. The world as it appears in his work — as a place where global power brokers act with huge and often dire consequences — resonated with their experience. These were elite students who had graduated into the economic mess he described in Crashed. And if his own students have fared remarkably well (Tooze Boys can be found on the tenure track at Georgetown, Columbia, and Cornell), there are a legion of podcasters, reporters, tweet threaders, and think-tankers with similar pedigrees and fewer prospects.

This demographic may not have institutional power, but it sometimes has the ear of people who do. In corporate settings, in government settings, at economic ministries, “all the analysis is done by people in their 30s,” said Tim Sahay, a senior policy manager at the Green New Deal Network and one of Tooze’s friends. “Those are the people who have been paying attention to Adam.” In the offices of Senators Chuck Schumer and Elizabeth Warren, Sahay told me, there are staffers for whom Tooze’s work serves as “a kind of secret handshake.” (He saw shades of Tooze in the Build Back Better climate legislation, which combined economic and CO2 modeling.)

During the pandemic, the ranks of the Tooze Bros grew. Matthew Zeitlin, a reporter whose Tooze enthusiasm was perhaps the first I registered, remembered that in spring 2020, Tooze “was on a podcast every other day.” In Zeitlin’s most vivid memory of the early pandemic, he is simmering dried beans, he is listening to Tooze talk about the Treasury market on a podcast, and he is thinking, I’ve done this so many times.

Tooze’s wife, Dana Conley, runs a boutique tour company, and during the pandemic, her work disappeared. Tooze was busier than ever, meanwhile. He set aside the book he had been writing about the economics of the climate crisis and began to think and write about the COVID crisis instead; that book, Shutdown, was published last year. In 2020 and 2021, he started first a Substack called Chartbook, then a podcast called Ones and Tooze. Both allow him a wide-ranging mandate to explain numbers in the news. Tooze told me that a model that guides him is the BBC in its public-spirited educational heyday. A flautist in his youth, he fondly recalls an hour-long radio program dedicated to “discussing different recordings of late Beethoven string quartets, comparing passages.”

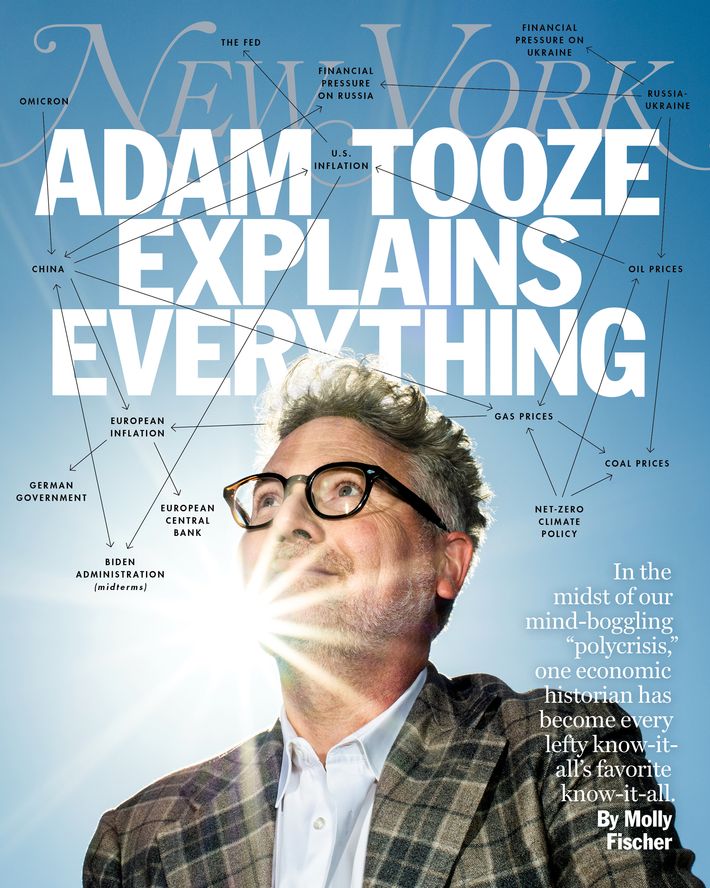

In January, he devoted an installment of Chartbook to mapping “the polycrisis we are in.” This polycrisis encompassed Omicron, U.S. inflation, European inflation, the need for net-zero climate policy, and the potential for war with Russia in Ukraine. “It comes from all sides and it just doesn’t stop,” Tooze wrote. “In German there is a compound noun: Krisenbilder — Crisis Pictures. I am going to draw some Krisenbilder.” What followed — the Krisenbilder — were thickets of color-coded arrows, increasingly dense, connecting such entities as “oil prices,” “ECB,” and “Biden admin (midterms).” Among them, further graphs charted the state of Ukrainian government debt, American oil prices, and E.U. gas imports.

“The German philosopher-historian Reinhart Koselleck spoke of the gap in modernity between the space of experience and the ‘horizon of expectation,’ ” Tooze concluded. “Given our present mood, talk of a horizon of expectation feels like a rather pastoral image. What these Krisenbilder sketch is more like a mind map of our fears. But, with Koselleck, let us hope that these fears do remain on the horizon.”

Another model Tooze said he looks to in his role as public intellectual is that of his maternal grandparents. “Leading synthesizers of global data on childhood nutrition,” Peggy and Arthur Wynn published research on poverty and family policy and together wrote a pseudonymous book attacking Tory business connections called England’s Money Lords. (Arthur was also, for a time, a Soviet-spy recruiter at Oxford.) They continued their work into their 90s. Arthur died over his word processor one night after Peggy had gone to bed; he was making a list of things to do.

It was in 2020 that Rachel Millman, a social-media editor at the Observer, noticed something afoot among her male friends. It began with a man she described as “aesthetically, a Long Island bro to the core — the accent, the flat cap, the polo, all of it” but “also a dedicated DSA member.” One day, the pair was hanging out when an alarm on her friend’s phone whipped him into action. “He was all, ‘Oh, there’s a Tooze talk I have to watch right now,’ ” Millman said. As another friend, then another, professed their devotion to Tooze, a phenomenon took shape in Millman’s mind. “Guys only want one thing and it’s fucking disgusting,” she tweeted above a screenshot of Tooze’s Twitter profile. Now, when a note-worthy piece of Tooze content “drops,” the tweet recirculates. (“I accidentally created the Bat-Signal,” she told me.) Because Tooze, like his fans, is constantly on Twitter, he too came across the tweet. He was alarmed at the possibility that it might imply something untoward; when he DM’d her, Millman reassured him otherwise. In her mentions, she watches as Tooze fans find a community she calls “the Beyhive of nerds.”

“Every dude on here’s dream blunt rotation is Mike Davis, Adam Tooze, and Fidel Castro,” tweeted journalist Aaron Freedman recently. “And there’s nothin wrong with that.”

Last year, the journalist Alex Yablon sent out a newsletter diagnosing the emerging Tooze phenomenon. (Under the heading “Tooze Clues,” it included Tooze’s bespectacled, beard-flocked face Photoshopped next to cartoon dog Blue.) Yablon, a self-described “dilletantish liberal-arts type,” wrote that he had undergone a pandemic-inspired conversion to caring about the economy. He and his wife had been counting on universal pre-K to make New York affordable, and now the program’s future seemed in doubt. “I became obsessed with the debates over federal, state, and local fiscal policy in spring 2020 out of naked, immediate self-interest,” he wrote. “Once I finally tuned in, I found that the economic-policy consensus felt more up for grabs than at any point in my lifetime.” Back when he was graduating from college, circa 2008, he and his friends had talked over beers about topics like fiction and indie rock; now they talked about the E.U.’s carbon border-adjustment tax scheme. “We joke about becoming ‘Tooze pilled,’ ” he wrote. A large part of Tooze’s appeal is that he “suggests that this stuff is comprehensible,” Yablon told me. “In 2008, I didn’t feel like that.”

“Is there a word for members of the Adam Tooze fandom,” wondered journalist Brendan O’Connor on Twitter last fall. What to call them? Tooze Boys, Tooze Bros, Tooze Hounds, Tooze Heads, Tooze Dudes, Toozers. (“Tooze Bro,” in my experience, seems to come up most often in relation to online fans, “Tooze Boy” in relation to students. I have heard, secondhand, of a complaint that everyone says “Tooze Bros” and no one says “History Boys.”) The name is contentious, the appeal inarguable. “For the Tooze Bros, what Adam does is he validates the little-boy interest in big machines and great men playing Risk while also embracing all the left-wing, anti-imperial, 21st-century politics we’re supposed to have,” said Ethan Winter, an analyst at the think tank Data for Progress. “That’s very fun.”

The media contingent of Tooze’s fan base are readers who relish a chance to “feel marginally superior to Matt Yglesias,” as journalist Alex Pareene put it. Tooze conveys substance — a sense of undeniable expertise — in a way few of his fellow explainers can match. “It’s remarkable the breadth of things he covers,” Pareene said. “It puts the rest of us to shame. You check his newsletter and it’ll be like, ‘Here’s the economic implications of what’s happening in the Ukraine. Here’s a complex discussion of cryptocurrency, which I don’t even like talking about yet I can talk about at length.’ And then everyone else is like, ‘Here’s a woke college student who complained in a meeting.’ So many other public commentators — it illuminates how parochial their concerns are.”

Tooze joined Twitter in 2015, at the suggestion of his teenage daughter (now a Columbia junior), and took to the medium energetically. “Every day, I can see him basically live-tweet-reading the Financial Times,” Pareene said of Tooze — partly under his inspiration, Pareene recently subscribed. The Tooze Bros look upon his productivity in wonderment. “It is mind-boggling. Beyond mind-boggling. I mean, I’ll see him tweeting at 4 a.m. sometimes,” Williams said. “I do that sometimes, but that’s really a mistake. That’s a problem for me.”

In the seven years that he has been tweeting “intensively,” Tooze believes he has managed to avoid significantly offending anyone. For him, the app has provided a cordial and sustaining intellectual community. “Those are my peeps,” he said. Twitter has “become far more important for me than academic seminars.” Lately, he said, the writing he enjoys most is “the short tempos” — the articles, newsletters, and other commentary. He suspects the climate book he is working on now will be the last he writes for some time. Since the beginning of 2022, Tooze has published eight articles in The New Statesman, Foreign Policy, and The Guardian; 40 editions of Chartbook (not including link roundups); and 1,500 tweets.

“The man’s output is insane,” said Winter. “He just crushes content. I have no idea how it’s possible.”

Never before have I written a story with which my male peers were so eager to help. They sent tweets, they sent podcasts, they proposed merch. “I really want to make one of those ’90s pop-star shirts for tooze,” one enterprising friend texted, along with a Backstreet Boys Etsy link. Maybe this is what Tooze feels like all the time, I thought — carried along by great gusts of boyish enthusiasm, lavished with informative chats. It felt good.

The texts arrived in a flurry when, in February, Elon Musk tweeted about Tooze. The Tesla co-founder had jumped into an exchange about the Canadian truck blockade to recommend The Wages of Destruction. “Well thank you @elonmusk much appreciated!” Tooze responded. Musk had cited the book in the course of comparing Justin Trudeau to Adolf Hitler. This came to Tooze’s attention only later. At the time, Tooze had been distracted: He was flying to the Bahamas, where he and his wife are rebuilding their house, which was destroyed by Hurricane Dorian. “I wish I had been more on top if it,” he told me. “But my initial impulse when somebody says something nice about my work is to simply say thanks.”

In the acknowledgments to Shutdown, Tooze thanks two therapists by name; in Crashed, he thanks an anonymous psychoanalyst. For a time, he was doing three psychoanalysis sessions per week, though lately he has cut back to two. “It helps me sort through the psycho-intellectual dramas of high-stakes intellectual life,” he said, such as interviewing Timothy Geithner. (“He lays a trip on you,” said Tooze of the former Treasury secretary. “He is a little Napoleonic figure. He’s very charismatic. He’s playing with your mind; he’s playing with your emotions.”) On a more quotidian level, “it helps me manage the fears around writing.” Despite his graphomaniacal recent output, Tooze has grappled with insecurity and writer’s block over the years. “I was an economist as an undergraduate. I wasn’t in a writey-writey discipline,” he said. “I didn’t think of myself as a writer.”

Sometimes the dramas of intellectual life take the form of reviews. “A lot of my graduate students had to talk me down after the Anderson piece,” Tooze said. In 2019, he was waiting to board a transatlantic flight in Paris when he received an email from Susan Watkins, editor of New Left Review. Tooze had contributed to NLR in the past, and Watkins was writing to share an essay on his work it would publish in a few hours. Tooze remembers struggling to download the text on his phone as he boarded the plane — “a horrific situation,” he said. The piece, when it arrived, was a long and scathing critique by Perry Anderson. Coming after Crashed had amassed a year of acclaim, its publication was “like watching gods fight,” one Tooze fan told me. Anderson cast Tooze as insufficiently critical of power, a thinker whose posture amounted to “running with the hare and hunting with the hounds.”

It is true that Tooze’s work deals almost exclusively with the doings of a tiny, powerful elite. This is his method and the basis of what fans on the left see as his critique. As Tooze put it to me, “If you want to do critical analysis of contemporary capitalism, stick with the trouble, stay inside the machine. Follow the people who are operating the machine and you’ll be amazed what they’ll tell you. Absolutely staggering what they will say out loud.” He sees his work as offering, in “quite explicit” terms, a class politics for his educated, white-collar readers — the professional-managerial class, or PMC. “It’s a matter of holding ourselves as the PMC responsible for our catastrophic fuckups,” he said. “In argument with Perry Anderson and people like that, I’ve become more and more conscious of this. It’s a kind of class politics. It’s a PMC class politics.” (He also said, “I mean, look at me, for crying out loud. I cannot be the bearer of a populist politics.”)

Reading Anderson’s account of his work left him “vaguely sick” and “dizzy”; he felt “travestied” and “misunderstood.” But Tooze, who describes his politics as “left-liberal,” was accustomed to political scrutiny. “My lefty friends in the United States were so disappointed in me for using the word ‘liberal’ about myself,” he said. He didn’t quite understand why it bothered them until witnessing the “full-on self-celebration of New York Times liberalism” in the wake of Biden’s election. “Nevertheless, you don’t need to witness that to know that liberalism has blind spots. It must have. All ideologies do. But it really has lots, and to my mind, reading Marxism has always been the most powerful corrective to that.” Tooze is a figure with unimpeachable Establishment credentials who takes the left seriously. The combination has made him, in the words of one Tooze Bro, “the only person who can make credible, respected appearances at the Verso loft or at Davos.”

Recently, an invitation to deliver a particularly prestigious lecture “unleashed a complete crisis,” Tooze told me. The honor was an occasion for “incomprehension and panic and almost shame — impostor complex.” The solution he and his analyst devised was to focus on what he might usefully say. Just be useful: This directive has of late become his “principal stabilizing device.”

“I’m no longer, I would say, principally driven by a striving for distinctiveness or radical originality or those things,” he said. (“Though obviously — and it does happen to me — when you come up with an original idea, it’s great.”) Shutdown, for example: “The purpose of that book is to be useful,” he said. “People need to understand what happened in the bond market last year, and most people don’t. So let’s really explain it and link it up to all the other things that happened and provide a map. And write that book, and write it quickly, and get it out, and like — it’s useful.”

Russia’s war on Ukraine, it soon developed, was yet another disaster that put Tooze’s services in demand. It was a crisis that entangled military strategy, diplomatic power, and international finance; it concerned both European history and the economic machinery that churned within global politics. It was textbook Tooze terrain. One night in early March, a week into the invasion, I received an email from him. “No doubt there are more important things to write and think about right now,” he wrote. “But this is a chronicle of a week in the life of Tooze.”

Below was a schedule listing some 21 items, which included giving interviews, filing articles, and attending a National Security Council advisory session on Indo-Pacific strategy. Tooze reported that he had just finished a 14-hour day that began with talking to Der Spiegel and ended with talking to Chris Hayes. Still outstanding were requests from 13 established organizations and outlets as well as six or so from “podcasts, etc.” whose names he did not recognize. He had taken to using two computers at once to ease toggling between events. “Plus,” he wrote, “many of the interviews and panels I’ve been doing are in German. So I get confused, at times, about what language I am in.”

On Ones and Tooze, he explained the fine print on energy sanctions; in The New Statesman, he explained Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. “Who do you think has gotten less sleep the last two weeks,” a friend later texted me, “Putin or Tooze?” The need for explanation was evolving so swiftly that Ezra Klein had interviewed Tooze twice in the space of four days. “In a moment like this,” Tooze wrote in an email to me at 10:56 p.m., “if folks feel I can help make sense of things, I am all in. I will work around the clock.”