In 2001, as he set out on his first, disastrous campaign for public office, Andrew Cuomo invited a columnist for this magazine to join him for a car ride through New York City. Bill Clinton had just departed office, leaving Washington in Republican hands after being impeached over his sexual relationship with an intern who worked for him, and Cuomo, the youngest member of his Cabinet, was impatiently angling to run for governor against George Pataki, the man who had defeated his father, the liberal giant Mario Cuomo. The story’s dynastic elements were irresistible, but the younger Cuomo sought to downplay them, portraying Clinton as his true model, emphasizing what he had learned from watching the master tactician.

In the backseat of his car, Cuomo deconstructed Clinton’s use of physical contact, clasping the (male) columnist’s shoulder, holding his hand, stroking his knee. “He knew every nuance of what he was doing,” Cuomo explained. “The effect of touching you there, or touching you here.”

You can say this for Andrew Cuomo: He always knew what he was doing — he was able to dissect, with a clinician’s eye, the many ways in which a man in power could control, dominate and humiliate those he touched. “You can’t build something …” he said, 20 years later, on the phone on the Friday morning after his shocking resignation. He paused and searched for the right metaphor for his heavy-handed philosophy of governance. “You can’t talk a nail into going into a board. You can’t charm the nail into a board. It has to be hit with a hammer.”

It was three days after he’d admitted defeat in a characteristically strange self-justifying, un-self-aware speech, and yet he was on the phone still fighting, spinning, waxing philosophical, relitigating, questioning the motivations of the people who benefited from his removal. He sounded calm and self-assured, even upbeat. He spoke in his usual musical lilt, drawing out vowels, asking himself rhetorical questions and providing the answers, a Socratic habit he picked up from his father. He went on like this for 80 minutes. He said he thought he would have won an impeachment trial but was leaving to spare the state further convulsion. He claimed, however implausibly, one more time, that he had no idea how his words and gestures would be interpreted by the women who gave damning testimony against him.

For those who watched Cuomo closely as he guided New York through the pandemic — commandeering ventilators, raising field hospitals, reassuring the public that a strong hand was in control — it had been disorienting to see him lose his grip so swiftly. Almost as disorienting as it had been to see him become, for a surreal, transitory moment last year, a beloved figure, unrecognizable to the political class he was known to terrorize. “I literally am not any tougher than I need to be to get the job done, because I understand there’s a price of being tough,” he said. “There is no long-term path to be a strong executive without being strong.

“And people resent the strength.”

The end came in the form of a report, produced by State Attorney General Letitia James and released to the public on August 3. Cuomo knew it would be embarrassing, but he’d preplanned a defense, his own 85-page rebuttal and a 14-minute video with an awkward photomontage of him innocently kissing and hugging all sorts of people. But it was far worse than he imagined, with more women — 11 in all — and more devastating details of harassment than he was prepared to counter. Worst of all, in the view of the governor’s dwindling number of defenders, were the allegations of a young female state trooper on his personal detail, who testified to investigators the governor alluded to her sex life and ran his hands over her body. Even friends who doubted the credibility or seriousness of the other accusations were aghast. “That trooper story, there’s just no explanation for that,” one person close to the governor said.

He quickly lost the support of his once pliant allies in the State Legislature, labor, the Democratic Party apparatus, and the New York business interests that had propelled him. “As cuckoo bananas as he is, his approach to governing is a pretty stable one, and he keeps a sort of political and ideological equilibrium,” a real-estate executive said shortly after James released the report. “What has happened in the last 72 hours is his existence has become destabilizing.” After a spell of denial, Cuomo realized he had just one lever left to pull. Almost no one was sorry to see him go.

The day afterward, one of the grand old men of New York State politics, former MTA chairman and onetime lieutenant governor Dick Ravitch, was asked to share his thoughts on the governor’s stunning fall. “Let me begin by saying I’ve known him a long time,” said Ravitch, who has a rich history of antagonism with the governor. “I think he’s a son of a bitch.”

The resignation rumors had been flying for days — especially after his loyal adviser Melissa DeRosa quit over the weekend — but it was still hard to believe that he would really give up. For ten minutes, sitting in a cold conference room at his office on Third Avenue, staring into a camera, he made his case. He was sorry. He didn’t mean what the women thought. His enemies were out to get him, as usual. “Rashness has replaced reasonableness,” he said. “Loudness has replaced soundness.” It wasn’t a valediction; it was justification.

Karen Hinton — a former Cuomo aide who wrote a column in the Daily News in May describing his alleged harassment, bullying, and practice of “penis politics” — was watching on her laptop in the living room of her home in New Orleans. “I thought, Well, shit — you know, this is more of the same,” she said.

“Now, you know me,” Cuomo was saying. “I’m a New Yorker, born and bred. I am a fighter, and my instinct is to fight through this controversy because I truly believe it is politically motivated. I believe it is unfair and it is untruthful, and I believe that it demonizes behavior that is unsustainable for society.”

“I was thinking, Okay, I hear the ‘but’ coming,” Hinton said.

“If I could communicate the facts through the frenzy, New Yorkers would understand.”

There it was: If. With that syllable, Governor Cuomo’s political existence became conditional.

In fact, New Yorkers understood him all too well for entirely too long. He was almost Trumpishly incapable of ever conceding an inch of ground, and appeared to be willing to do anything, however brutish, to survive. He didn’t seem to care a whit that Joe Biden and every Democratic official of any importance in the state had called for his resignation. Most worryingly to many in Albany, he seemed almost certain to win reelection next year, damn it all. But in that moment, the consummate maneuverer conceded he was out of moves. “Government really needs to function today. Government needs to perform,” he said in his speech, sounding at least to himself magnanimous.

It’s already difficult to imagine how it went on this long. Everyone knew what he was. Just open up the thick, dog-eared file of his press clippings. “The antipathy toward him,” Adam Nagourney of the New York Times wrote of Cuomo in 2002, “is visceral, driven by a vague impression that he is pushy, ambitious and too urgent in pursuing his career.” Eight years later, his colleague Jonathan Mahler wrote: “That Cuomo has become New York’s dominant Democrat figure is something of a political miracle.” Five years later, here’s Jeffrey Toobin of The New Yorker: “He is the uncommon elected official with a streak of misanthropy.”

Many people in New York politics seemed to be of the view that, gross and demeaning as Cuomo’s behavior with the women who worked for him was, it was only a symptom of a weird and disturbing power pathology. The 165-page report was accompanied by hundreds more pages of evidence in three appendices, offering damning documentation of the steps that Cuomo’s inner circle took to discredit the women — leaking personnel files of Lindsey Boylan, his first accuser, and manipulating a young woman into recorded phone conversations — and ripping open for the first time the culture of absolute fear and paranoia that pervaded his office. Of course, it was only the revelation of it that was stunning.

“The abuse detailed in the report was just one manifestation of the fact he has been governing by extortion and threats for his entire tenure,” said a former high-level state official and Cuomo antagonist, who called as he was enjoying a celebratory beer. (Many of those interviewed for this article requested anonymity because, even after his disgrace and resignation, it was still impossible for them to believe that Cuomo was really, truly finished in politics or incapable of someday seeking revenge.) “The arc of his entire career,” he said, “is one of thuggery.”

In his youth, Cuomo made his reputation — and an enduring nickname, “The Prince of Darkness” — as the right hand of his father, whom he always addressed as “Mario.” Cuomo the elder was on the verge of political oblivion after multiple losses when he turned, for lack of other options, to his eldest son to manage his long shot 1982 campaign for governor. Andrew was a student at Albany Law School and had a weekend job in Queens driving a tow truck. But under the 24-year-old’s management, the campaign won a huge upset over then-Mayor Ed Koch. Andrew took a dollar-a-year salary and an impressive office on the second floor of the State Capitol Building. He was a trusted adviser and, people in politics whispered, the old man’s goon.

The rap carried more than a tinge of ethnic stereotyping — Mario was the first Italian American to be elected governor of New York — but it stuck, in part because Andrew was happy to play the tough guy. He was an operative, and an operator. He enjoyed the company of reporters, who shared his interest in the inside game. In 1988, he roared around with a writer from this magazine in his light-blue Corvette Stingray, chain-smoking Parliaments and telling indiscreet stories. “I’m talking to a reporter once,” Andrew said. “He says, ‘Well your father is very liberal.’ I say, ‘Liberal! Liberal!’ I say, ‘This is an Italian guy, grew up in South Jamaica, Queens. I’m 18 years old, I’m still waiting for my talk on sex!’ Boom! That was the lead! So the next thing you know, this book arrives in the mail.”

The hardbound volume was titled A Compendium of Advice to My Son Andrew on Matters of Sex, by Mario Cuomo. Inside, all the pages were blank.

As a pair, the Cuomos defied the immigrant-assimilation cliché. Mario thoughtful, urbane, smooth around the edges. Andrew somehow felt more first generation: “A man of unseemly hunger,” in the words of a political writer who encountered him early in his rise. The origins of that hunger were not hard to guess. For all his beautiful oratory and public rumination — the “Hamlet on the Hudson” routine — Mario was a blank page when it came to his son: distant, unappreciative, imperious. Andrew wanted him to run for president in 1992, at a time the Democratic Party looked to be theirs for the taking, but Mario frittered away the opportunity. Andrew wanted Mario to accept a nomination to the Supreme Court the following year, when Bill Clinton broached it, but Mario took a pass. In 1994, he lost the governor’s office to Pataki, a nonentity propped up by another family enemy, then-Senator Alfonse D’Amato. “Maybe the people just didn’t like Mario Cuomo,” the defeated governor moped to a reporter.

Andrew had little to do with that race. By then, he was well in the midst of his metamorphosis into his father’s heir apparent. He was hardly the first hotheaded son to follow his father into politics, but the younger Cuomo’s route was characteristically overcrafty. It was as if he had set out to remake his life to attract regular coverage in the New York Post. He became an urban problem-solver, founding a nonprofit to take on the crisis of homelessness, which had reached dire levels in New York City. He courted an idealistic young woman, Kerry Kennedy, daughter of RFK, taking her out on his motorcycle to a housing project on their first date. “How do you think it will play?” he asked his reporter friends before he asked her to marry him, according to Michael Shnayerson’s biography of Andrew, The Contender. The engagement party was held at McFadden’s, a newsroom watering hole on Second Avenue. His sometimes pal Donald Trump, who had given Mario campaign donations and later raged at him when he wouldn’t get Andrew to do him a favor at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, sent a videotaped testimonial. “Whatever you do,” advised the developer, then in the midst of his Ivana divorce, “don’t ever, ever fool around.”

After Clinton hired Andrew for an undersecretary position at HUD in 1993, he and Kerry had moved down to Washington, where they lived at Hickory Hill, her late father’s suburban estate in Virginia. When the HUD secretary resigned amid a criminal investigation involving payments to a mistress, Cuomo was promoted to the top job. He quickly became known as one of the administration’s most politically savvy Cabinet members, and he surrounded himself with a loyal crew, including an ambitious up-and-comer named Bill de Blasio. Andrew was gunning to run for something. In 2001, he declared his candidacy for governor at a shoe store owned by his brother-in-law, Kenneth Cole.

That first campaign was the sort of experience that would have forever leveled a less-formidable ego. Andrew never managed to articulate a rationale for running. The plan seemed to be to use his family name, his Kennedy connections, and his force of will to win the nomination over Carl McCall, the state comptroller who was vying to make history as New York’s first Black governor. Andrew fumbled the obligatory stuff. He couldn’t line up the unions behind him. And he couldn’t make himself likable. He made dismissive remarks about Pataki’s performance after September 11: “Rudy Giuliani was the hero of 9/11. He held the leader’s coat,” Andrew said, which made him look like a twerp.

Facing certain defeat in the primary, Andrew dropped out. Soon afterward, Kerry demanded a divorce. Andrew’s lawyer put out a statement saying she had “betrayed” him and soon word of an affair leaked to the tabloids. Meanwhile, Pataki defeated McCall and went on to tie Mario Cuomo with three terms in office.

Andrew later called this his life’s low point, and during his career’s next act, he portrayed the humbling as a formative experience, giving birth to a new man. (“Andrew 2.0,” some in Albany called him.) In practice what that meant was that he stripped his political identity down to its ruthless core and rebuilt himself from there.

After a few years working for a real-estate investor who was also his chief fund-raiser, Andrew entered a crowded race to succeed Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, who was running for governor. He allied himself with Jennifer Cunningham, the political director of a powerhouse health-care union that had endorsed Pataki (helping him to beat McCall). Cunningham helped him to reintroduce himself to the big institutional players he had previously alienated in his youthful arrogance. Gone were the freewheeling jaunts with reporters; the new Andrew model was tightly controlled and seldom spoke on the record.

Andrew won the primary and easily defeated Republican Jeanine Pirro, whose campaign foundered when it emerged she was under federal investigation for allegedly proposing to bug a boat owned by her husband, whom she suspected of cheating. (She was never charged with a crime.) Then Governor Spitzer resigned when it was revealed he’d been a client of a prostitution ring. Then Spitzer’s successor, David Paterson, dropped his election bid after a series of scandals, including one over his attempts to quash a domestic-violence complaint against a top adviser. The road to the Governor’s Mansion was clear. With rivals like these, who needed friends?

Just think about what we did,” Cuomo said on Tuesday, speaking — for the first time — about his tenure in the past tense. “We passed marriage equality, creating a new civil right. Legalized love for the LGBTQ community, and we generated a force for change that swept the nation. We passed the SAFE Act years ago, the smartest gun-safety law in the United States of America, and it banned the madness of assault weapons.” The governor went on, reviewing a decade of balanced budgets, college-tuition benefits, new infrastructure.

Cuomo styled himself as a man who got things done, a master builder in the tradition of Robert Moses. He knocked down the rickety Tappan Zee Bridge and replaced it with a new, $4 billion span which he named after his father. “It’s on time and on budget,” Cuomo boasted, although neither thing was completely true. He opened it by driving across it in FDR’s Packard. Later, a whistleblower would claim that Cuomo’s administration had covered up structural deficiencies, one area that legislators were exploring in their now suspended impeachment hearings.

He constructed roads, subway lines, airport terminals. He was a gearhead. Even as governor, he liked to get under the hood with his cars. “Mechanical work,” Cuomo told Politico in a profile published on March 13, 2020. “It’s linear and it’s numerical and there are no emotions and there are no personalities and there’s no foibles. It’s predictable.” Then, within a few days of that story’s publication, an unpredictable catastrophe threw the whole world into chaos.

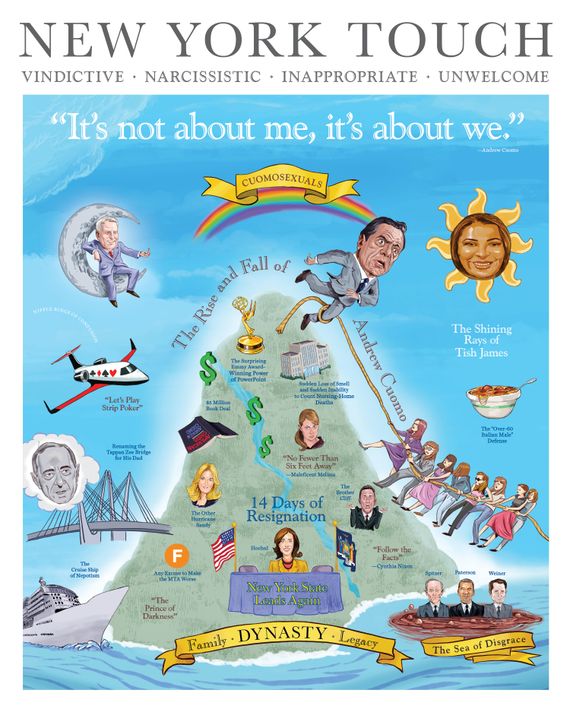

If history is kind, it will remember him for the One Big Thing he got at least superficially right, the COVID crisis, where he played the role of the calm, rational national leader, a counterweight to the maniac in the White House, winning an Emmy for his press conferences. In retrospect, the pandemic was, tragically, his finest moment. Fans declared themselves to be “Cuomosexuals.” (A clothing company that sold sweaters embroidered with the term is now offering to restitch them with a slogan of the buyer’s choice.) Cuomo, a natural scowler, soaked up the glow. Last summer, he unveiled an old-timey-looking poster, a map of the COVID “mountain” filled with illustrations representing the most colorful bits from his press conferences. (He was depicted in his Pontiac GTO, running his daughter’s boyfriend — the butt of his dad jokes — off a cliff.)

Crown gave him a ridiculous $5 million advance for a memoir, American Crisis: Leadership Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic, which unfortunately came out as a second wave of COVID was starting to swell. It soon was overshadowed by the scandal that did him in. (It has sold fewer than 50,000 copies.)

In his resignation speech, Cuomo listed what he got done over the past 11 years, but not how: by practicing a style of politics distilled by a then-senior aide: “We operate at two speeds here: Get along and kill.” Cuomo won legislative battles by outsmarting and outworking his opposition and, when the first two tactics didn’t work, bullying them. In 2011, he threatened not to legalize taxis in New York City’s outer-boroughs if the Bloomberg administration didn’t agree to a deal that would potentially cost the city hundreds of millions of dollars in health-care expenses for public employees. “He was just a miserable fucker on the taxi thing,” Bloomberg’s former chief Albany negotiator Micah Lasher recalled of Cuomo. “It was just a straight-up shakedown.” Lasher felt especially free to opine on the episode in part because “Saddam has been toppled. These don’t need to be state secrets.”

Managing the press was as critical to Cuomo’s government as managing the government. He read all his own print news coverage (it took him a while to move to the internet) and, early in the morning after a critical story was published, would dispatch his aides, or sometimes just call himself from an unlisted number, to scream at reporters and their editors about the tone of the coverage or the headline. After de Blasio was elected mayor of New York City, he promptly turned on his onetime ally and started working him like a heavy bag, screwing with him on policy matters and pummeling him in thinly veiled quotes to the newspapers. (Once, Cuomo accidentally outed himself as the anonymous “administration official” who called the mayor “bumbling and incompetent” in The Wall Street Journal and lampooned him in the Daily News.) Aides would threaten to go over an editor’s head to the publisher, or to pressure advertisers to pull their dollars from news websites. Cuomo and his people felt no compunction about weaponizing details of critics and journalists’ lives, going so far as to compile a dossier on a reporter’s “snarky” journalism. Rumors swept the rooms of the Capitol where the press corps worked that Cuomo’s aides were going to extreme lengths to monitor reporters. One prominent journalist talked about raising funds to hire surveillance experts to sweep the press room for bugging devices.

Cuomo saw no distinction between his personal life and his work, and he expected the same of his closest aides. He was possessive of staffers’ time and controlling about their careers. Cuomo routinely pressed people who’d left the administration back into service, whether to help construct PowerPoint slideshows for his annual State of the State speech or to run crisis comms when he got in trouble. Ex-aides had to seek and receive Cuomo’s blessing when they sought new employment or risk losing their new job offers. “The odd part about these workplace stories,” Cuomo’s former chief of staff Josh Vlasto texted to a friend as the sexual-harassment scandal was breaking, according to investigators, “It’s not even close to what it was really like to work there day to day. It was so much worse.”

It was no accident that Melissa DeRosa, who would eventually rise through the ranks to serve as Cuomo’s secretary, the highest-ranking unelected official in the state, was first hired in 2013 as his communications director. She embraced his reputation as an intimidator, and her persona as one of his “Mean Girls.”

The irony was that, even as COVID put him at the peak of his might — in March 2020, the State Legislature granted him temporary emergency powers that gave him dictatorial authority to enact new laws by decree — he was already starting to lose control. In 2018, the Democrats had won the State Senate, which perversely was bad for Cuomo, since he held more sway over a divided legislature than a united, progressive one. Most of the powerful aides who served him in the early years were gone, whether because they were burned out, discarded, or banished for some real or perceived act of betrayal. He had broken up with his longtime companion, TV chef Sandra Lee. His cheating was “an open secret,” the Post reported last April, citing unnamed sources, in an article that claimed Lee had grown tired of what she saw as inappropriate relationships with other women, including staff members. (“It’s not true, and the New York Post’s reporting standards are subterranean,” said Cuomo spokesman Rich Azzopardi.) This left him, by his own admission, lonely, even before COVID.

Cuomo’s downfall began with his threatening someone who dared fight back. One evening in February, Assemblyman Ron Kim, one of those pesky newly empowered progressives, received a call from the governor as he was putting his kids in the bath. Kim, who believed his uncle had died of COVID in a nursing home, was pushing to investigate the administration’s alleged cover-up of the scope of the death toll in such facilities. Cuomo gave him the usual treatment, but to the shock of Albany, Kim struck back, going on CNN and claiming the governor said “he can destroy me.”

“The bullying is nothing new,” chimed in de Blasio. “There are many more of us, but most are too afraid to speak up,” declared Lindsey Boylan, a former state official who was running for borough president in Manhattan, in a post on Medium, expanding on what she had previously described in a Twitter thread as a pattern of persistent sexual harassment by the governor. She claimed he had asked her to play “strip poker” during a flight on a taxpayer-funded jet and, later, gave her an unwanted kiss in his Manhattan office.

Her earlier allegations, though vague, had mostly fallen into a void — in part because, behind the scenes, Cuomo’s top aides had mobilized to discredit her with reporters.

DeRosa, the chair of the New York State Council on Women and Girls, who’d championed the state’s paid-family-leave law and legislation ensuring insurance covered fertility treatments, and who’d appeared just months earlier on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar under the heading “Voices of Hope,” spearheaded the campaign to damage Boylan. She got ahold of her confidential personnel files, which leaked to reporters. A spokesperson described this effort as “correcting the record.” According to the report, a female former staff member testified that “at the insistence of Ms. DeRosa,” she called up a woman who had worked for Cuomo and secretly taped their conversation in an effort to find out who Boylan was talking to and whether any other women might accuse the governor.

Then came another crisis: In January, Attorney General James released a report finding the administration had, in fact, undercounted COVID deaths of nursing-home residents and in February audio leaked of DeRosa telling legislators that she’d delayed giving them an honest tally of how many thousands of elderly and sick people had died. Later that month, a 25-year-old former aide named Charlotte Bennett came forward to say Cuomo had made overtures to her about having a sexual relationship. Other allegations emerged, and Cuomo was soon facing calls for his resignation.

Cuomo sought to slow the process by commissioning an investigation headed by a hand-picked private attorney. When that blatant gambit failed, he turned the matter over to James, who hired a real team of investigators, including Joon Kim, a veteran of the corruption investigations conducted by former U.S. Attorney and Cuomo bête noire Preet Bharara. DeRosa requested the state’s vaccine czar, a former Cuomo aide, to ask county executives to stay quiet until the investigation concluded. “I ask the people of this state to wait for the facts from the attorney general’s report before forming an opinion,” Cuomo said in March. State Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and some of the Democrats in his conference “pumped the brakes” on their own plans for an impeachment investigation, an assembly member said. As winter turned to spring and then summer, Cuomo seemed to be prepared to ride out the siege, and turned his sights toward a fourth term.

Meanwhile, to Cuomo’s dismay, James was conducting a serious investigation. Current and former aides were subpoenaed for personal emails and messages. They sat for lengthy depositions. Rich Azzopardi, Cuomo’s current communications director, recalled Kim asking him during his own deposition whether the governor, in a fit of rage, had ever thrown fruit at Azzopardi — specifically, dried apricots. It didn’t happen, Azzopardi said, but he recalled investigators threatening to lock him up if he talked to anyone about the substance of his testimony before the report was published. (A spokesperson for the attorney general’s office declined to comment.) In otherwise mundane conversations with reporters, senior aides began making unsolicited, nervous jokes about going to jail.

Cuomo sat with investigators for 11 hours in mid-July. Soon after, his surrogates openly attacked James and the investigation as having a “transparent political motivation” and suggested she was using it to destroy Cuomo and clear her own path to run for governor. The report was expected to land around Labor Day, and they were hard at work undermining it. Instead it arrived with no advance warning to Cuomo’s team at 11 a.m. on Tuesday, August 3.

The report hit the Capitol like novichok. Cuomo started working the phones, trying to find support, but allies poured forth to condemn him over the report’s findings. There was no more talk of a fourth term. “The question was survivability, not electability,” one ally said. “Electability was not even on the table past lunchtime on Tuesday.”

The day of the report, Cuomo talked on the phone with Jay Jacobs, the chairman of the Democratic State Committee and a friend. Jacobs encouraged Cuomo to hold a press conference to defend himself. It was set for 11 a.m. the next day, Wednesday, August 4. “I said that there’s no way this tidal wave that is coming is going to be survivable unless you’ve got something compelling to say that’s going to change its course,” Jacobs said. “The governor was — I wouldn’t say arguing, but he was pretty clear that he felt he could change its course, that the investigation wasn’t legitimate on either the process or the merits.”

But Wednesday morning came and Cuomo never showed. It seemed to Jacobs that Cuomo and his aides “were just trying to run the clock at that point, to play for time.” Jacobs told Cuomo he was planning to call for his resignation, and shortly after 3 p.m. he did. So did Heastie, who said, there were enough Democratic votes in the assembly to impeach the governor.

Cuomo, holed up in Albany in the gloomy and ornate redbrick gingerbread mansion on Eagle Street, worked the phones each day, seeking affirmation for his plan to keep fighting from a small, shrinking circle of advisers, including longtime friend Bill Mulrow and powerhouse political consultant and lobbyist Charlie King and his brother, Chris; his sister, Maria; and his daughters. Friends who spoke to him compared the process of counseling him toward resignation to palliative care for a patient who refused, in spite of all reason, to accept his terminal prognosis.

Heading into the weekend, Cuomo was still telling allies he intended to fight, sending out three of his attorneys to hold a jaw-dropping virtual press conference attacking both Cuomo’s accusers and the investigators’ methods. One of them, his personal attorney Rita Glavin, reiterated the counterattack in lengthy appearances on television. But the accusations couldn’t be shouted down. The executive assistant who accused him of groping her in his office filed a criminal complaint and went on television to tell her story. On Sunday, DeRosa, under an avalanche of bad press, saw that Maureen Dowd of the Times had written a devastatingly sharp piece accusing her of enabling Cuomo’s predatory behavior. DeRosa announced her resignation in a statement that night.

In a last-ditch effort, Cuomo dispatched intermediaries to try to talk to people close to Heastie and several other assembly members to find out if they would be willing to cut a deal, such as promising not to run for a fourth term if the Assembly would not impeach him. But Cuomo didn’t take “no” for an answer until Monday afternoon, when Heastie unequivocally dismissed the idea of a deal during a press conference.

“If he saw any possible way out, any possible deal that could have been worked out with the legislature for him to leave more gracefully, he would have kept fighting,” one person close to Cuomo said. “But there was just no path, and for once in his life, there was no one around him to even tell him there was a path.”

How are you?”

“Philosophical, philosophical,” Cuomo said, on the phone on Friday.

“What does that mean?”

“You know, I consider myself a student of history and I see everything through that lens.”

He wanted to talk about his legacy, to solicit a reporter’s opinions. How would his accomplishments compare to those of past governors? How would he be remembered? Implicitly, he was asking, would what he was accused of overshadow the things that got done?

“I feel like I did the right thing. I did the right thing for the state,” he said of his resignation. “I’m not gonna drag the state through the mud, through a three-month, four-month impeachment, and then win, and have made the State Legislature and the state government look like a ship of fools, when everything I’ve done all my life was for the exact opposite. I’m not doing that. I feel good. I’m not a martyr. It’s just, I saw the options, option A, option B.”

Or might there be an option C? Among the political cognoscenti, the preoccupying question last week was whether he might still spring through some secret trapdoor. Was it really possible, after 3,875 days as governor, and decades of omnipresence in New York political life, that Andrew Cuomo could just leave with so little drama or ceremony, like he was clicking the red button on his Zoom?

The cynics seized on the 14-day transition period he laid out in his speech. Bharara issued a statement saying he hoped “there’s nothing nefarious about the 14 days” and calling Cuomo a “person of mischief.” Beyond that, Cuomo still had more than $18 million in his campaign account, and there is another election coming in 2022. He is still only 63 — 15 years younger than the president of the United States. “Unless he’s actually convicted in a court of law of committing crimes,” one Cuomo adviser said, “who’s to say he can’t come back?”

For now, though, it is hard to see an angle. He has no obvious political heirs. Some of the big things he wanted to get done — redeveloping Penn Station and the area around it, the train to La Guardia airport — probably won’t happen. Other infrastructure projects, like the new $11 billion train terminal and tunnel beneath Grand Central or the Second Avenue subway extension, long predate his involvement and won’t require his presence at the ribbon cutting. The moderate, pro-business, Clintonian brand of politics that he practiced was in retreat long before Cuomo was overtaken by his personal failings. “He was an extremely effective governor for the first eight years, and he kept things balanced,” said Kathryn Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City, the business lobbying group. “For the last three years, he was on the defensive.”

When Cuomo got on his state helicopter at the 34th Street heliport and flew back to Albany on Tuesday, he left behind a city that is still reeling from the effects of a pandemic that has emptied its office buildings, shaken its tax base, and left its schools and subways in a disordered state. Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul, who is positioned to take over as the state’s first female governor, is an unknown quantity, facing a legislature that has grown emboldened in pushing an agenda of tax increases, rent regulation, and other measures that many in the business community consider antithetical to the city’s recovery. “The governor is a world-class asshole,” one New York real-estate developer said — but, he added, “the guy was an incredibly centrist hedge against what I perceive to be a runaway legislature. He was very good at manipulating the power of his office, and I think from a policy standpoint the business community has to be afraid of the State Legislature becoming fairly unhinged and flying too far to the left.”

But big business can always find another protector. Eric Adams is making reasonable noises. Maybe Hochul, a moderate, will offer the same ideology without the agita.

“I don’t think he was a bad governor,” said Dick Ravitch. “He’s definitely not a nice human being, though.” And that mattered more than what he was able to deliver. “He has no friends. There was nobody willing to stand up for him and say ‘This is bullshit.’ ”

Jay Jacobs, who talked to the governor again the day he resigned, said that Cuomo was planning to use his final two weeks in office to wrap up his work. “There’s a lot of i’s to dot and t’s to cross, and I believe he’s rushing through that,” Jacobs said. He also has practical preparations to make. By New York standards, he is not an exorbitantly wealthy man, although that book advance and the $50,000-a-year pension he is eligible for should help to tide him over.

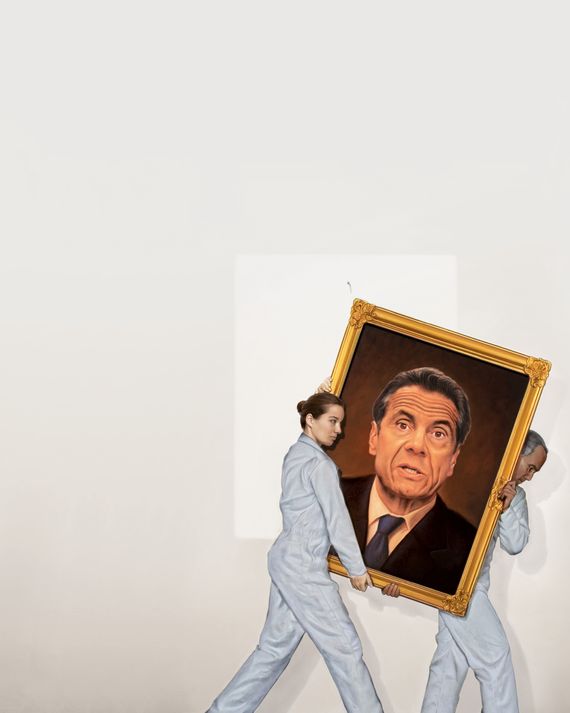

“He also has to figure out what his living will be when he moves out of the mansion,” Jacobs said. “He’s got a lot of packing to do.”

“Uh, I don’t know what I’m gonna do,” Cuomo said, when asked about his immediate plans, like where he was going to live. “I’m not disappearing. I have a voice, I have a perspective and that’s not gonna change. And the details aren’t really that important to me to tell you the truth. You know? I’m a New Yorker, I’ve lived here, I’ve lived in Queens, I’ve lived in the city, I’ve lived upstate, I’ve lived everywhere, I came to Washington, so that’s … I don’t really care about that. I’ll figure that out. And I think I did the right thing.”

After his breakup with Sandra Lee, she sold the home they shared in the Westchester suburb Mt. Kisco. Since then, his only residence has been the mansion in Albany that has been occupied by members of his family for 21 of the last 38 years. Without it, Andrew Cuomo is homeless.