This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Chuck Schumer had the ease of someone already on summer vacation. “I’d much rather be in New York than Washington any day of the week,” he said during a Zoom conversation from his Manhattan office in mid-August. The Senate Democrats had just passed the Inflation Reduction Act, a climate and tax law that constitutes the centerpiece of Joe Biden’s reform agenda, and as the majority leader responsible for saving this legislation — and, perhaps with it, Biden’s presidency — from what appeared to be certain defeat, Schumer could be forgiven for not merely taking a well-earned break but also resting on his laurels a bit. “People are just so positive,” he gushed, claiming that Democratic incumbents in battleground states are thrilled to run on the IRA in the upcoming midterms. “They said they’ve never seen more energy.”

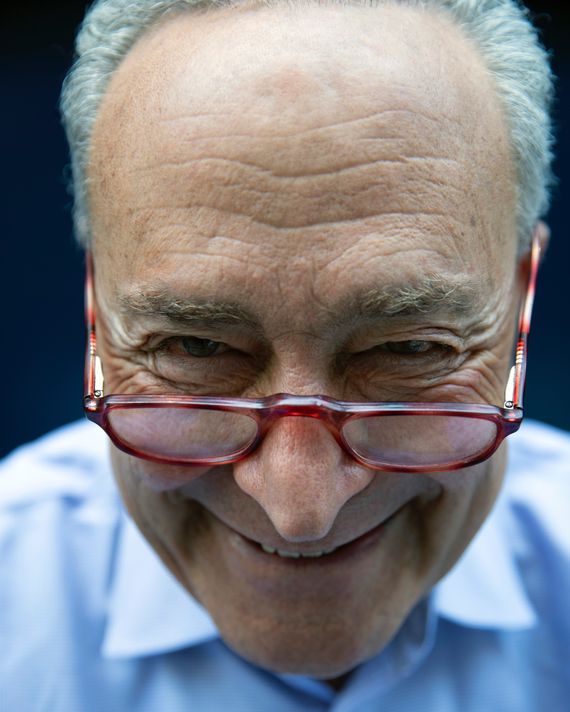

It’s a remarkable turn of events for the longtime senator from New York, who is less Master of the Senate than Master of the Schmooze — a reputation he credits for his success. Schumer merrily showed off his infamous tool of the trade, a flip phone, holding it so close to the camera that a speck of dust on the screen was visible. “I talk to every member,” he told me. “And they all have my phone numbers. They don’t go through staff; they talk to me directly. I’ll probably get ten, 12 calls a day from members on an average day, maybe more.”

For Schumer, it was a chance to take a bow after long being in the shadow of Republican and Democratic legislators who were considered superior tacticians. He has outmaneuvered Mitch McConnell in the eyes of some Senate Republicans (he got “rolled” by Schumer, Mike Braun of Indiana told the Daily Beast) and surpassed his predecessor as majority leader, Harry Reid. The Democrats, who possess the thinnest of majorities, have passed a robust infrastructure package, gun-control measures, funding for scientific research and semi-conductor production, and massive pandemic-relief bills, often with bipartisan support. But more than anything, it is the IRA, with its investment in green energy and its prescription-drug reforms, that proves the Democrats can fulfill their campaign promises and gives their base a reason to support them in the fall. “We got a lot done,” exulted Schumer. “It’s pretty historic. It’ll compare to Congress decades ago.”

Casting some shade at Reid, whose style tended more toward menace than mensch, Schumer described his constant encouragement of his fellow Democratic senators over the past two years. “I tell every one of us that we have to be a team, we have to stick together. And I also encourage members when they disagree to voice it. We have a caucus. You know, in the previous caucuses, people were sort of afraid to bring up their points of view. I made sure that we all bring up our points of view but have respect for one another even when we disagree.”

Still, Schumer’s path to legislative victory was much like the route of the G train in his native borough — it twisted, it turned, and it showed up way behind schedule. All that talk, all that agreeing to disagree, dragged on for months and months, pushing Biden’s approval ratings down to the basement. Schumer seemed to have no coherent strategy for getting all 50 Democrats to support the same bill. At one point last summer, Schumer and Joe Manchin signed a joint statement of principles in support of a bill with up to $1.5 trillion in new spending, though Schumer noted in the margins that he “will try to dissuade Joe on many of these” limits. At the same time, progressives were hoping for a $3.5 trillion bill. Schumer tried to put together a package designed to appeal to seemingly everyone in his fractious caucus, which ended up displeasing everybody — including, most important, Manchin, who could make or break the party’s agenda. Eventually, progressives were ready to yield to the West Virginia senator. (“Give Manchin what he wants already,” wrote New York’s Eric Levitz in January.)

In the end, the Democrats got a smaller $750 billion package — not because Schumer strong-armed Manchin into playing ball but because the mercurial senator eventually decided this summer that he wanted a deal. Schumer and his staff “were shocked,” according to a person familiar with the negotiations. Schumer and Manchin entered into secret talks — conducted away from prying eyes in the bowels of the Capitol, then over Zoom when Manchin came down with COVID — surprising McConnell, the Democratic caucus, and the Beltway press when they emerged into the sunlight with a bill. Schumer had just one negotiation left with the enigmatic Kyrsten Sinema, who agreed to sign on if Schumer killed a provision closing a tax loophole largely used by hedge funds and private equity.

To Schumer’s credit, he never wrote Manchin off as a lost cause, putting himself in a position to close the deal. “The fact that it took Schumer lacing up his pumps and hitting the last-second buzzer beater, you have to look at that in its own right,” said Liam Donovan, a veteran Republican lobbyist. “You can question the methods, but the execution in the end is really all that matters.”

“It’s a different way of getting things done,” Schumer told me. “It’s sort of my Brooklyn way of getting things done. Sometimes it helps me, sometimes it hurts me. But if I tried not to be from Brooklyn, I’d be different. I’d be worse than whatever I am.”

For the time being, his approach has united a diverse caucus and convinced

the left to hold their noses and cave to Manchin’s demands, including a carve-out to finish the construction of a natural-gas pipeline in West Virginia. “I have some climate hawks, you know, some people really strong on climate — it’s their passion,” said Schumer. In his telling, in a meeting in the spring, they told him, “Look, we have to get something done. We’ll have your back if you have to put some things in that aren’t good.”

Schumer commended the energy of activists who have criticized him, comparing it to the days when he protested against the Vietnam War. “I hated that fucking war,” he said with still-palpable scorn a half-century later. “I tell the people who picket outside my house who are very progressive, ‘If I were you, I’d be doing just what you’re doing. And it’s a good thing. But if you were me, you’d be doing what I’m doing, which is taking some of that energy and trying to translate it into getting things done, even if it’s not everything we want.’ ”

Schumer was now filled with optimism that his legislative achievements would yield wins for Democrats in the midterms. While he acknowledged that outrage over the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade was driving the surge in enthusiasm among Democrats, he also attributed their zeal to the party’s successes in Congress. “There’s the specifics in the bill, which are large, the biggest change in decades. But it’s also the idea that Democrats actually could get their act together even under these difficult circumstances and get something done.” He was convinced, too, that Biden’s numbers would improve, even after the gridlocked Senate had done so much to bring them down. “I think he’s done a very good job,” said Schumer. “But I think, you know, there are things that people are very, very cranky about: inflation. COVID. And he’s not to blame for those, but he’s the leader.”

Can Schumer wrangle anything more out of the Senate in the next couple of months? His two most maverick caucus members, Manchin and Sinema, have been sparring with each other with Manchin recently blaming Sinema for watering down provisions aimed at bringing down prescription-drug prices. “We had a senator from Arizona who basically didn’t let us go as far as we needed to go with our negotiations,” Manchin said. Schumer also has to appease progressives who feel the IRA fell short of their expectations and are still reeling from the Supreme Court’s abortion decision in June. But then again, that’s why he has the flip phone.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage. If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the August 29, 2022, issue of New York Magazine.