This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Republicans have begun saying things about American schools that not long ago would have struck them as peculiar, even insane. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida has called schools “a cesspool of Marxist indoctrination.” Former secretary of State Mike Pompeo predicts that “teachers’ unions, and the filth that they’re teaching our kids,” will “take this republic down.” Against the backdrop of his party, Donald Trump, complaining about “pink-haired communists teaching our kids” and “Marxist maniacs and lunatics” running our universities, sounds practically calm.

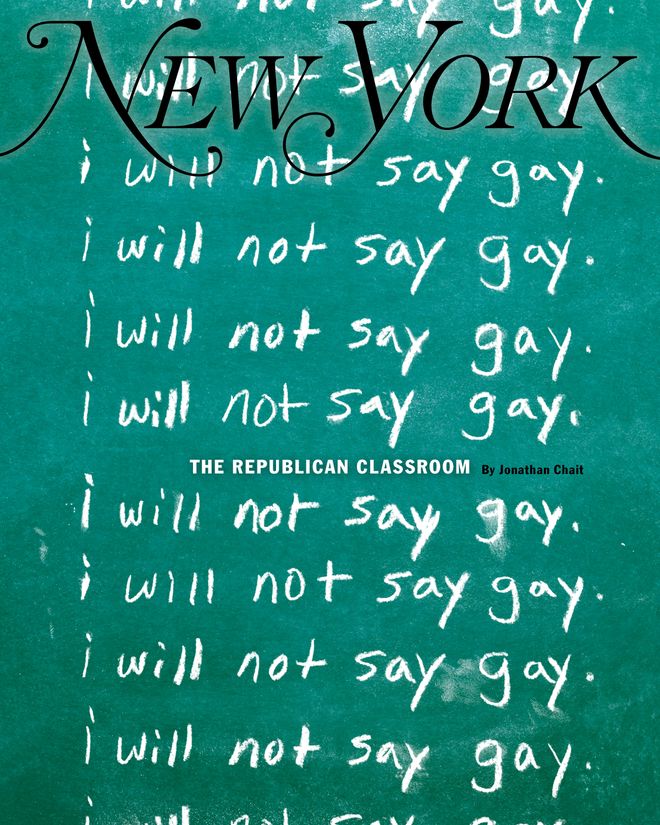

More ominously, at every level of government, Republicans have begun to act on these beliefs. Over the past three years, legislators in 28 states have passed at least 71 bills controlling what teachers and students can say and do at school. A wave of library purges, subject-matter restrictions, and potential legal threats against educators has followed.

Education has become an obsession on the political right, which now sees it as the central battlefield upon which this country’s future will be settled. Schoolhouses are being conscripted into a cataclysmic war in which no compromise is possible — in which a child in a red state will be discouraged from asking questions about sexual identity, or a professor will be barred from exploring the ways in which white supremacy has shaped America today, or a trans athlete will be prohibited from playing sports.

In the spring of 2021, Richard Corcoran delivered a fire-breathing speech at Hillsdale, a right-wing Christian college in Michigan, touting the agenda he had helped implement as education commissioner in Florida. When an audience member asked how he had been able to find common ground with people who disagreed with him, Corcoran responded, “I have fought … There’s no negotiation. I don’t think antifa wants to sit down and have a conversation with me about how can we make this society better.” Corcoran went on to compare America’s disputes over education to “the warring in the streets” in Germany before World War II between the Nazis and the communists. “The war will be won in education,” he vowed. “Education is our sword. That’s our weapon. Our weapon is education.”

Cover Story

It is hardly novel for Republicans to emphasize the need to improve schools. Ronald Reagan’s administration published a report, A Nation at Risk, that inaugurated the modern education-reform debate. Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, claimed he would be “the education president.” Bush’s son, George W., signed the No Child Left Behind Act, a historic education reform that used testing to hold schools to account. What little attention Trump paid to education when he ran for president in 2016 gestured in this direction, championing educational choice as a tool to lift student achievement. All these Republican executives saw education as a technocratic issue they could use to appeal to voters outside their base.

What sets the current movement apart from these previous efforts is not merely its greater intensity but its focus. Academic-achievement levels are incidental to Republicans’ concern. Their main preoccupation is not the ways in which Chinese and Swedish kids may be outpacing their American counterparts. They are instead accusing schools of carrying out an insidious indoctrination campaign that, they believe, poses an existential threat to their party’s future and their way of life.

Dubya once said, famously, “Rarely is the question asked, Is our children learning?” The complaint of Republicans today is not that the schools aren’t working but that they are working all too well at the objective of brainwashing children in left-wing thought. Education, as Corcoran reportedly put it, is “100 percent ideological.”

Media coverage of the Republicans’ education crusade has largely treated it as a messaging exercise. A New York Times headline from earlier this year, “DeSantis Takes On the Education Establishment, and Builds His Brand,” reflects the cynical assumption that this is mostly a way for him to rile up the Fox News audience. One progressive pollster recently told The Atlantic that for Republican voters, liberal control of schools “is a psychological, not policy, threat,” even as their elected officials strike back with policy. Some Democrats have mocked Republicans for pursuing arcane obsessions that fail to connect with voters’ concerns. And it’s true the voters are not driving this crusade: A recent poll found only 4 percent of the public lists education as the most important issue. Politico reports that “mounds of research by Democratic pollsters over the last several months” have found Republican book bans to be utterly toxic with swing voters.

You might wonder why Republicans would throw themselves into such a risky venture. The answer is that they aren’t looking to enrage their base or get their face on Fox News. They have come to believe with deadly seriousness that they not only must but can seize control of the ideological tenor in American schools, from the primary to the university level. If accomplishing this social transformation carries a near-term political cost, they are willing to pay it. And to imagine that they will fail, or grow bored and move on, and that the education system will more or less remain the same as it ever was, is to lack an appreciation for their conviction and the powers they have at their disposal to realize their goal.

Culture wars can break out over almost anything, but the political content of education is the most classic venue. Kulturkampf, the German word for “culture struggle” and the linguistic origin of “culture war,” describes a wrenching conflict over whether the church or the state would control the schools in 19th-century Prussia. Around the same time, France had a similar schism, largely between monarchists and republicans, both of whom believed that if they controlled the schools, they would own the hearts and minds of future citizens.

The nature of these fights is raw. Schools are a foundational institution for inscribing the value system of the state. Nothing enrages parents more than the idea that their children are being turned against them, and few things worry a partisan more than the fear the opposing party is using schools to inculcate its beliefs in the young. “Wherever two or more groups within a state differ in religion, or in language and in nationality, the immediate concern of each group is to use the schools to preserve its own faith and tradition,” wrote Walter Lippmann in 1928. “For it is in the school that the child is drawn toward or drawn away from the religion and patriotism of its parents.”

France’s conflict eventually led to the Dreyfus affair, in which false charges of treason against Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery captain, unleashed a torrent of antisemitism that pitted much of France’s secular republican left against the theocratic monarchist right. Germany’s Kulturkampf preceded … well, you know.

It was perhaps just a matter of time until the Republican Party’s perambulatory culture-war fixations, which have roamed from hippies to flag-burners to Muslims to gay marriage, landed on the schoolhouse.

Throughout American history, fights over the political content of school have broken out from time to time, usually centering on history textbooks and their treatment of racism, immigration, communism, and other social divides. Generations of conservatives have been shocked by the experience of their children reporting some unattractive facts about the Founders or the Civil War and came to suspect educators were plotting to steer children to some new worldview.

Some progressive education reformers embraced this very goal. George S. Counts, an educator and activist who went on to serve as head of the American Federation of Teachers and founded New York’s Liberal Party, wrote a pamphlet in 1932 called Dare the School Build a New Social Order? in which he argued frankly that schools should be used to inculcate progressive beliefs. “Progressive education,” he wrote, should “become less frightened than it is today at the bogies of imposition and indoctrination.” He added, “Every Progressive school will use whatever power it may possess in opposing and checking the forces of social conservatism and reaction.”

Later that decade, a number of history textbooks written by Harold Rugg swept into popularity. The Rugg history scalded the Founders as aristocratic landowners using the Constitution to preserve their wealth from the masses. Critics denounced it as left-wing propaganda, while his supporters insisted that educators alone were qualified to choose the proper historical emphasis. “Judgment as to the merits of a textbook is the function of those most competent to form a judgment: the teachers concerned and professional scholars,” maintained the American Historical Association.

As the New Deal lost momentum in Washington, Rugg’s ideas, held aloft by the assumption that liberalism had entered a new permanent ascendancy, fell out of favor. Sales of his texts plunged from a peak of 289,000 in 1938 to just 21,000 half a dozen years later, and they soon dropped out of usage altogether. The heady liberal dream that schools could serve as a vanguard of a social revolution had met political reality.

After the Rugg conflict, American history and civics texts generally adopted a mushy, consensus-oriented tone that offended very few people. Among the aggrieved minority was William F. Buckley Jr., who shortly before the founding of National Review in 1955 helped establish a publication called the Educational Reviewer dedicated to demanding right-wing content in the schools. Buckley’s first book, God and Man at Yale, proposed that the left-leaning faculty be denied academic freedom, which, he charged, they were abusing to warp the minds of impressionable college students.

Buckley is generally credited as the founder of the modern American conservative movement, but his call to conscript schools into the cause of promoting right-wing thought, like many of Buckley’s ideas, failed to catch on at the time. As Jonathan Zimmerman recounts in Whose America? Culture Wars in the Public Schools (2002), the campaign to censor textbooks never made it far in the halls of power after World War II: “Even at the height of its frenzied search for subversion,” the McCarthy era, “Congress refused to extend the quest into textbooks.”

Eventually, the fights over indoctrination largely receded. “By the early 1980s, the shared sense across the political spectrum that public schools were sites worthy of intense contestation began to diminish,” writes education historian Natalia Mehlman Petrzela in Classroom Wars (2015).

The return came very fast at a magnitude and with a vehemence unlike anything that has ever occurred in American history.

The Republican Party emerged from the Trump era deeply embittered. A large share of the party believed that Democrats had stolen their way back into power. But this sentiment took another form that was not as absurd or, at least, not as clearly disprovable. The theory was that Republicans were subverted by a vast institutional conspiracy. Left-wing beliefs had taken hold among elite institutions: the media, the bureaucracy, corporations, and, especially, schools.

This theory maintains that this invisible progressive network makes successful Republican government impossible. Because the enemy permanently controls the cultural high ground, Republicans lose even when they win. Their only recourse is to seize back these nonelected institutions.

“Left-wing radicals have spent the past 50 years on a ‘long march through the institutions,’” claims Manhattan Institute fellow and conservative activist Chris Rufo, who is perhaps the school movement’s chief ideologist. “We are going to reverse that process, starting now.”

Many institutions figure in Republicans’ plans. They are developing proposals to cleanse the federal workforce of politically subversive elements, to pressure corporations to resist demands by their “woke employees,” and to freeze out the mainstream media. But their attention has centered on the schools. “It is the schools — where our children spend much of their waking hours — that have disproportionate influence over American society, seeding every other institution that has succumbed to left-wing ideological capture,” writes conservative commentator Benjamin Weingarten.

Or, as Florida governor Ron DeSantis has said in his most revealing comments on the issue, “Our K–12 schools are public institutions that are funded by our taxpayers. And so that line of thinking is saying, even though they’re public institutions, the people that are elected to direct those institutions have no right to get involved. If the left is pursuing the agenda. So basically, we can win every election and we still lose on all these different things. That is totally untenable. So these are public institutions, and they have to reflect the mission that the state of Florida has in our case, not just K–12, but also higher education.”

A recent study by the Manhattan Institute illustrates why the right finds this cause so urgent. The paper surveys 18-to-20-year-olds about what it calls “critical social justice” concepts they learned in school, such as “America is a systemically racist country,” “white people have unconscious biases that negatively affect nonwhite people,” “America is built on stolen land,” or “America is a patriarchal society.” The survey proposes that adults exposed to these concepts develop liberal beliefs: “CSJ and school ideology appear to be having a major impact in converting young people to left-wing beliefs and Democratic partisanship.”

The report finds that these concepts are being taught in private, religious, and charter schools and spread through social media and entertainment. Therefore, the old conservative method of promoting choice between public and private schools stands little chance of holding back the progressive tide. The biggest shift among young people seems to have occurred among those whose parents were Republicans or independents.

Put aside for a moment whether this finding is correct. What it shows us is why Republicans are acting so urgently (or, to their bewildered critics, hysterically). They believe the schools have become factories for turning children into Democrats, that progressives are so powerful the children of Republican parents cannot resist them, and that their old remedy of exiting the public-school system is nearly useless. Working from these assumptions, Republicans’ determination to seize control of the indoctrination machinery makes perfect sense.

Even the most paranoid belief systems often contain elements of reality. It is true that American society has polarized, pushing its most conservative communities rightward and its liberal communities leftward. Schools, largely being run by people who have college educations, have likely undergone the same kind of socially progressive shift that has rippled through the rest of the knowledge economy.

In California, public schools are rolling out required ethnic studies and have pushed schools to decelerate adoption of algebra in order to advance equity goals. Thousands of classrooms have used the New York Times’ “The 1619 Project,” a provocative interpretation of American history that has drawn criticism from some respected historians, including one approached by the Times to fact-check it.

Some teachers and administrators see the role of the school, like Rugg and Counts did, as a vanguard institution driving social change. In 2021, the National Education Association approved a resolution for “increasing the implementation of culturally responsive education, critical race theory, and ethnic (Native people, Asian, Black, Latin[o/a/x], Middle Eastern, North African, and Pacific Islander) Studies curriculum in pre-K–12 and higher education.” The NEA can’t simply dictate classroom pedagogy, but its desires do reflect a popular sentiment within the profession that has left its mark on many classrooms. A national report by Bellwether, a nonprofit firm analyzing education, reported, “Much of the backlash to teachers’ efforts to teach about racism in the classroom or to DEI trainings comes from lessons and programs that are poorly designed and poorly implemented, often because of limited or nonexistent resources and support or politicized approaches.”

Many parents, understandably, don’t like this stuff. A poll last year by the American Federation of Teachers found that voters would be more likely to support a Republican candidate who endorsed propositions like “public schools should focus less on teaching students about race and racism, and more on core academic subjects,” giving parents more say over content, and other right-leaning criticisms of the pedagogy. The idea that some schools have gone farther left on social policy than the public as a whole shouldn’t come as a surprise. Progressive educators can implement change that’s far more radical in character than anything Democrats could pass in Congress.

It is possible for legislatures to restrict some of the pedagogical fads of recent years without preventing children from learning unvarnished historical truths about slavery, reconstruction, Jim Crow, and its aftermath. Reports have described bans on lessons that make students feel guilty, when they have merely restricted lessons that instruct them to feel guilty, a reasonable thing to ask. Commentators on the internet likewise depicted Florida as banning the teaching of African American history, when in fact the state merely objected to elements of the AP African American History curriculum, ultimately resulting in a revised version.

And aspects of the Republican legislation confines itself to these limited measures. But other bills attempt far more expansive levels of ideological control over the classroom, and they suffer from either sweeping vagueness or paralyzing specificity.

As an example of the former, a Montana bill currently tabled in committee would restrict science education to “scientific fact,” defined in the bill as “an indisputable and repeatable observation of a natural phenomenon,” which would present a serious challenge to teaching a field composed in large part of scientific theories. A South Carolina bill introduced in 2021 would have forbidden any lesson that “omits relevant and important context” and created a hotline to report violations of this hopelessly subjective criteria.

An example of the latter can be seen in an Oklahoma bill that tried to stamp out social-emotional learning, a strategy to help students manage their emotions that conservatives have bizarrely associated with indoctrination. (“The intention of SEL,” Rufo has claimed, “is to soften children at an emotional level, reinterpret their normative behavior as an expression of ‘repression,’ ‘whiteness,’ or ‘internalized racism,’ and then rewire their behavior according to the dictates of left-wing ideology.”) But how can a legislature ban an entire style of teaching? The solution settled upon by Oklahoma would have prohibited an array of concepts so vast it has to be beheld in its entirety:

Any evidence-based or non-evidence-based programming that promotes school or civic engagement or builds an equitable learning framework that creates or uses evidence-based benchmarks, standards, surveys, activities, learning indicators, programs, policies, processes, professional development, or assessments that address noncognitive social factors including but not limited to self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, responsible decision-making, and other attributes, dispositions, social skills, attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, feelings, emotions, mind-sets, metacognitive learning skills, motivation, grit, self-regulation, tenacity, perseverance, resilience, and intrapersonal resources.

Imagine attempting to teach a class for a year while keeping this entire list of forbidden ideas in your head at all times.

A broader problem with the wave of conservative legislation is that it is responding to a wildly hyperbolic version of reality. In a very large country with a fragmented education system, there are going to be plenty of examples of outrageous or radical teaching in the schools on a daily basis without necessarily indicating anything about the system’s overall character. As conservatives grew alarmed about left-wing teachers, their favorite media sources started curating examples of it to stoke their outrage.

Chaya Raichik’s account Libs of TikTok has amassed more than 2 million followers — DeSantis once invited her to stay at the governor’s mansion in Florida — partly by finding posts by left-wing teachers on social media. Her audience has come to see these cherry-picked examples as representing the normal experience in an American classroom. In response to a post by a teacher with brightly dyed hair and tattoos appearing to pledge allegiance to the Pride flag, National Review editor-in-chief Rich Lowry commented, “Don’t laugh — this pledge is probably coming soon to blue jurisdictions.” In apparent response to a viral but false Libs of TikTok post claiming a school was placing litter boxes in the bathroom for children who identify as cats, North Dakota’s House passed a bill that would, among other restrictions, forbid any “policy establishing or providing a place, facility, school program, or accommodation that caters to a student’s perception of being any animal species other than human.”

These sorts of lurid fantasies inspired Republicans in Florida, Iowa, and Mississippi to introduce bills to put microphones, cameras, or livestreams inside classrooms. An Indiana Republican bill proposed to require school officials to create parent-led curricular advisory committees. Louisiana attorney general Jeff Landry, who is running for governor, created a “Protecting Minors” tip line to field complaints about libraries and schools.

Inevitably, perhaps, conservative fears of sexual indoctrination have led them to seek out evidence of heresy in school libraries. Concerned parents have been pestering school boards to keep scary books away from little Susie’s innocent eyes since the school library was invented. But the movement to do so has taken on a wholly novel scale. PEN America, a literary-freedom organization, has tracked some 50 organizations dedicated to restricting library content — nearly three-quarters of which have formed since 2021. The most prominent, Moms for Liberty, presented DeSantis with a “liberty sword” when he spoke at its summit in July.

About two-fifths of the bans are tied to rules or political pressure from state officials or elected lawmakers, an “unprecedented shift,” according to PEN America, which notes that book bans have historically been initiated by locals in a community, not their governments. Seven states are considering bills to restrict books containing things like “profane language” or “depictions of gender identity.” Twelve states have introduced bills that could make school employees and librarians subject to being charged with violating obscenity laws.

In Florida, HB 1467 — a law requiring all books in schools to be “suited to student needs” — prompted school libraries across the state to frantically pull texts for fear they would violate the new regime. The Florida Freedom to Read Project reported that some 20 school districts in the state eliminated books to comply with this law or DeSantis’s “Don’t Say Gay” and Stop WOKE acts. School officials in two counties covered up all the books in the library until the entire catalogue could be vetted for compliance. “There appears to be confusion over what books or materials could actually lead to a criminal charge,” conceded a report in National Review. Citing DeSantis’s HB 1557, what critics called the “Don’t Say Gay” law, the Lake County district removed And Tango Makes Three, which tells the true story of two male penguins who had built a nest together in the Central Park Zoo, then, when provided an egg by the zookeeper, raised the baby penguin. The book contains no sexual content, not even between consenting penguins.

One of DeSantis’s allies has introduced a bill requiring schools to “teach that the male and female reproductive roles are binary, stable, and unchangeable” and another to remove children from their parents if a court deems that they have been “subjected to” gender-affirming care, making a mockery of their professed concern for parental rights. DeSantis’s state-imposed ideology is being extended to student-run clubs: One high school shut down a meeting by its Queer and Ally Alliance, a student group, after Florida’s Department of Education reportedly sent the school administration a threatening message. Both in theory and in practice, the Republican schools campaign has attacked even basic expressions of respect for gay and trans people.

The difference between the old conservative approach to education and the new variant can be seen most starkly in the realm of higher education. American conservatives have never exactly adored universities, and the feeling is mutual. One study found that left-leaning faculty members outnumber conservatives by about six to one, and among administrators the ratio is twice as high. For many years, conservatives have deplored the left-wing tilt of academia and supported the complaint, along with many moderates and liberals, that the hothouse atmosphere on campus was suppressing dissent.

Allan Bloom’s 1987 book The Closing of the American Mind and Dinesh D’Souza’s 1991 Illiberal Education expressed the conservative view of academia: It had become close-minded and abandoned its historic commitment to open inquiry. Conservatives joined groups like the National Association of Scholars to protect conservative professors — or a liberal one who happened to say something provocative — from being intimidated or fired.

In recent years, a rising class of conservative intellectuals has advanced a different critique. Rufo, in particular, has pressed the case that the far left has infiltrated schools and other institutions so thoroughly that conservatives must take drastic action. “We’re going to actually learn the left-wing playbook,” he vowed in one lecture, calling for a “counterrevolutionary strategy for recapturing the institutions.”

Like many radicals who studied the methods of their adversaries, Rufo seemed to come away not with horror but a strange respect. “One thing I almost admire about the political left is that they want to achieve dominance and nothing less than dominance,” he said. In other words, conservatives must discard their attachment to fusty principles of academic freedom and open debate. When laying siege to institutions, Rufo has said, “You have to be very aggressive. You have to fight on terms that you define. You have to create your own frame, your own language. And you have to be ruthless and brutal in pursuit of something good.”

Academic freedom is no longer the solution. It is now the problem.

The world of politics and activism has plenty of would-be Lenins, but few have a direct plan for conservatives to use their power of the state to shape the ideological character of schools. And the place demonstrating the feasibility of this method is Florida, which represents the most advanced proving ground of the right’s new campaign against education.

DeSantis has placed his stamp on K–12 schools with an array of creative methods. His law restricting gender education and another, the Stop WOKE Act, which bans the teaching of certain progressive racial theories, have both had a chilling effect on liberal teachers. He also held voluntary training sessions for civics teachers with the lure of a $700 stipend for those who attend and the chance to receive $3,000 if they complete an online course. The sessions, reportedly developed in part by Hillsdale, had a distinctly conservative slant, according to several attendees. “It was very skewed,” one government teacher told the Miami Herald. “There was a very strong Christian fundamentalist way toward analyzing different quotes and different documents.”

State and local governments traditionally observe some limits on their control of subject matter. DeSantis’s K–12 agenda has at least pushed that line. When it comes to universities, DeSantis has obliterated the line completely.

He began with a takeover of New College, a public university in the state, stacking its board with right-wing ideologues, several of whom have praised him, including Rufo.

The pretext for tearing down the school leaned heavily on its alleged budgetary woes, but DeSantis immediately allocated $15 million in state spending and the board hired Corcoran as president with a base salary above that of presidents of other Florida universities that have nearly 100 times more students. DeSantis hoped to turn New College into “Florida’s classical college, more along the lines of a Hillsdale of the South,” his chief of staff told the Daily Caller. “We are now over the walls and ready to transform higher education from within,” exclaimed Rufo.

Having supplied proof of concept, DeSantis is now turning to the other, vastly larger components of the state’s higher-education system. His allies have introduced legislation that would impose rigid ideological control over every state university. The original text of the bill held that no core American-history course could teach a narrative except one “based on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence” and shunted teaching any “unproven, theoretical, or exploratory content” to electives. The current version bars any general-education courses from teaching “theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, or privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, or economic inequities.”

To backstop these changes, DeSantis, who had already signed a law in 2022 scaling back tenure protections for faculty, is now considering all but doing away with them. DeSantis would additionally consolidate power over hiring and firing in the hands of university presidents, some of whom owe their appointments to DeSantis. Any professors wandering too close to his vague regulations on progressive thought could find their career at the mercy of political operatives.

Ken Burns, the documentary filmmaker, recently called the DeSantis education program Soviet, which is a tad melodramatic, given that the Soviets arrested or murdered millions and millions of people. But there does happen to be a comparison at hand that is chilling in its own right: the Hungarian strongman Viktor Orbán, whom DeSantis and the Republican Party have adopted as a model.

When he won his first election in 1998, Orbán identified the universities as the primary institutional source of opposition. Orbán placed most state universities under the control of close allies. He drove the prestigious Central European University, which had been founded by his enemy George Soros, out of the country — not by sending in troops to seize the school but through the blandly bureaucratic method of imposing new operating requirements.

At first, the scholar Kim Lane Scheppele noted at the time, his critics joked darkly that “since educated people don’t vote for Orbán, his long-term plan for staying in power in Hungary has been to create fewer educated people.” But Orbán’s vision turned out to be much more strategic than that. Universities cut back on academic departments with the most liberals and expanded funding for departments with conservative leanings. Orbán opened a lavishly funded new campus for conservative intellectuals. His supporters publicly invited students to submit the names of faculty who professed “unasked-for left-wing political opinions.”

Last September, Balázs Orbán, the political director for the Hungarian prime minister, visited Florida, where he praised DeSantis and likened his governing style to that of his own boss. Rufo just spent a month in Budapest as a fellow at the Danube Institute, a pro-Orbán group, where he gave speeches denouncing critical race theory and reportedly met with Orbán’s government. (Rufo declined to confirm whether they actually met.) The two men appear to be swapping notes.

DeSantis seems to have absorbed the notion that conservatives have an existential need to use their political power to seize the commanding heights of the culture, especially its schools. His new book argues against the old conservative notion of supporting academic freedom, warning that “elected officials who do nothing more than get out of the way are essentially greenlighting these institutions to continue their unimpeded march through society.”

Orbán’s example has shown the government’s power over the academy can be absolute. DeSantis is simply the first Republican to appreciate the potential of this once-unimaginable use of state power to win the culture wars. Even before DeSantis’s plan has passed, Republicans in North Carolina, Texas, and North Dakota rushed out bills to eliminate tenure for professors.

Trump, racing to catch up with DeSantis on the education issue, has vowed to eliminate federal funding for any school promoting critical race theory, “transgender insanity,” or “any other inappropriate racial, sexual, or political content on our children.” He promises to fire existing college accreditors and appoint new ones who will implement his ideological dictates, and to back up this threat by imposing confiscatory taxes on the endowment of any university that resists.

Conservatives as a whole have fled from any pretense of respecting academic freedom. “To complain that the governor and the state legislature are interfering with” public universities “is, in effect, to complain that the governor and the state legislature are interfering with the government that they run,” editorialized National Review, neatly sweeping away any concern that a Republican state could ever go too far in dictating content to its universities.

With DeSantis and Trump now vying for supremacy with a boot on the neck of American education, the Republican Party appears to have quickly settled on this strategy. There is not any assurance that the campaign to control the ideology of the schools will remain confined to the public sphere. Representative Dan Bishop of North Carolina and Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas have put forth a bill that would deny federal funding to public and private universities that promote CRT concepts.

And what has been revealed in these early days of the Republican plan to conquer the academy merely represents the powers of state governments. Should Republicans win control of the White House and Congress, they would have far more authority at their disposal. Federal research dollars and tuition subsidies give the federal government leverage over every institution of higher learning, public and private alike.

There is little sign Democrats have grasped the ultimate ambitions they are confronting. When DeSantis began pushing through yet another expansion of his restrictions on gender instruction — a bill that would, among other things, require “certain materials” facing objections by any parent to be removed before they were vetted — his opponents dismissed it as mere pandering. Democrats “see it as an attempt by DeSantis to excite the conservative base and, ultimately, win the GOP 2024 presidential nomination,” reported Politico.

This pat assumption fails to appreciate that seizing political control of the schools is not a campaign slogan. It’s a plan to turn power into more power.

When Republicans last had control of government, admiration of Orbán was confined to a marginal fringe of right-wing intellectuals, and the whole idea of imposing their will on schools had yet to be invented. It was well into his final year in office before Trump glommed onto the issue. Trump called the George Floyd demonstrations “the direct result of decades of left-wing indoctrination in our schools.” That is when he brought Rufo in for a visit and began ranting on the campaign trail about the “wokes” in the classroom. In November 2020, to counter the narrative of “The 1619 Project,” Trump created a “1776 Commission,” which released its report on Trump’s penultimate day in office.

This futile departing gesture seemed at the time to signify the superficiality and ridiculousness of the Republican interest in the subject. But now members of the party elite have fully invested themselves in this objective. They have only just begun to explore their powers, and their statements on the matter recognize no theoretical limit as to how far they might go. In retrospect, Trump’s late embrace of the crusade to purify the schools was not a fleeting interest but a new turn, the first shots fired in what we now see is a full-scale war.