This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

For the two and a half years that he was in charge, a Brad Parscale sighting was always news at Trump campaign headquarters in Rosslyn, Virginia. Parscale is six-foot-eight with a dagger of a beard and thorns for ears that give his head the shape of a spiked club, like a medieval morning star. So you can’t really miss him. But “there were times Brad might not be there for two to three weeks,” one campaign official told me. “If he wasn’t meeting with the president or going on the road, you weren’t seeing him. He was only around for the high-profile, celebrity things.”

“He was never there,” a senior White House official said. “He’d make phone calls from his house in Florida and brag that he was by the pool. And because he was never there, at the campaign office, people would leave at four o’clock in the afternoon.” (Jason Miller, a senior adviser to the Trump campaign, told me, “I’ve never FaceTimed Brad, so I cannot speak to what he is or is not doing while I’m on the phone with him.”)

It was a sign of impending doom, to some, when earlier this summer Parscale began coming in more often just as the target on his back swelled to carnival proportions. The polls? Trump trailed his almost-invisible challenger by double digits nationally and by a considerable margin in most battleground states. The messaging? Well, you try to “spin” six months in which 160,000 Americans died and at least 5 million more were infected by a virus you first said wouldn’t be much to worry about. Six months in which your best case for reelection — the greatest economy in the world — was destroyed too. The offense? Trump couldn’t even settle on a nickname for Joe Biden. Was he “Sleepy Joe,” or “Creepy Joe,” or “Beijing Biden”? That tiny Tulsa rally Parscale had organized — which followed weeks of massive hype — preceded a spike in coronavirus infections in the city that, local officials said, was probably born of the event, where the guest list included Herman Cain, who later died. Meanwhile, nationwide, there was civil unrest that Trump, whose political career had begun with a media tour to promote a racist conspiracy theory called birtherism, was unfit to handle. Yet there was an attitude, naïve and cocky, that led Parscale to compare the campaign to the Death Star, ready to fire but with no apparent idea where to aim. What was next? Locusts? How could the circumstances be any worse? The campaign was in a hole so deep it was actually historic — a deficit not just bigger, at this point in the race, than any an incumbent had ever overcome, but bigger than any an incumbent had ever even faced.

Even Trump was finding it more difficult to believe the fiction that everything was going great, and easier and easier to see the nihilistic wisdom of open warfare with the Postal Service in a way that might both cut Democrats’ likely vote-by-mail margins and delegitimize the election more generally. His closest advisers were now telling him that the bad numbers and bad reviews weren’t the fruits of Fake News or a deep-state hoax but a genuine reflection of what could happen in November. Though it took some time for him to accept it. The president recently asked a second senior White House official to review Biden’s performance after watching him speak. “I said, ‘I think if we lose to this guy, we’re really pathetic,’ ” the official told me. “The president said to me, ‘I’m not losing to Joe Biden.’ I said, ‘You’re losing to Joe Biden.’ ”

It was July before he “saw for the first time” that he could be defeated, according to the official. And he didn’t blame himself. He blamed a cruel world, a crueler media, and the Death Star’s failure to defend him from both. “They thought they were running one campaign: We’re on cruise control for the president who gave us the greatest economy of all time, and all the messaging would flow from there. Which socialist are we running against? Bop, bop, bop. And everything changed, and they didn’t change,” the senior White House official said. “The president started to hate the ads. He hated ‘Beijing Biden’ — he didn’t come up with that name.”

In the West Wing, officials filed away gossip and unflattering data points about the campaign manager as if drafting a dossier. When it was reported that Parscale’s web of companies took in $38 million between Inauguration Day and the spring of the pandemic, according to the Federal Election Commission, the story circulated widely. Though Parscale has declined to make clear what portion of his bills to the campaign amount to his personal salary, the New York Times reported in March that Trump had imposed a salary cap on Parscale of somewhere between $700,000 and $800,000 — enough for him to become in midlife a collector of luxury cars and seaside real estate, or at least a media caricature of one. But it wasn’t only Parscale’s spending on Parscale that worried — or “worried” — some of his colleagues; it was his spending on everything else, too, like the $15,000-a-month payments to Kimberly Guilfoyle, Donald Trump Jr.’s girlfriend, and to Lara Trump, Eric Trump’s wife, both of whom crisscross the country as campaign surrogates.

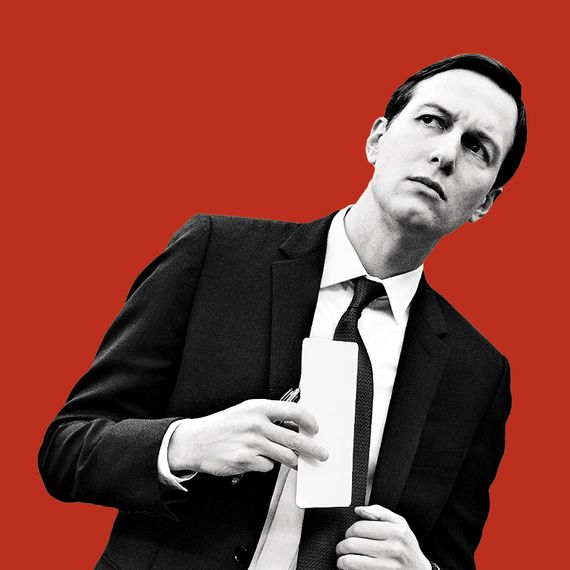

“The campaign was spending all this money on silly things. Brad’s businesses kept making money,” the first senior White House official told me. “Everyone was like, What does he even do? He’s just milking the family, basically. And nobody could understand why Jared and the family were putting up with it. That was the talk all the time. Why? Why Brad? He’s not some genius. And I guess people just came to the conclusion that, well, who else would be campaign manager? We’re kind of stuck with this guy.”

Parscale had abided needling before. That came with the job — the 2016 campaign had run on chaos, and this time around, nobody seemed inclined to do anything but up the ante. But as the campaign began to really falter, with Trump not just a little behind but a lot, Parscale became a human pincushion. The Lincoln Project, the group run by self-described “Never Trump” conservatives — members of what was once the Republican Establishment, like John Weaver, Steve Schmidt, and George Conway, husband of the counselor to the president, Kellyanne — bought up airtime in Washington, D.C., with the goal of forcing the president to view a 48-second attack ad about the personal wealth Parscale had accumulated in the four years since he started working for him during the last election. Trump did see the ad, and, later, he asked Parscale why it contained footage of “ass slapping.”

“The president wonders who’s truly loyal to him and who’s not and who’s making a buck on him,” George Conway told me, explaining that, from his perspective, “triggering Trump’s paranoia” is one way to defeat him. “It doesn’t matter who is the captain of the SS Trump, because Trump is the one who is going to run it into the iceberg in the end. If there’s more chaos, all the better. We try to trigger the chaos in Trump’s DNA.”

Even as representatives for the campaign insisted the press was wrong to report that Parscale was about to be fired, “anybody who knew anything knew it was just a matter of time,” the campaign official said. The second senior White House official added, “The Brad special-ops team had three weeks between Tulsa and his firing. They were saying, ‘Brad’s job is safe! Brad’s part of the family!’ Nobody was saying, ‘Is the president’s job safe?’ But the president started to ask that question.”

The president started asking other kinds of questions, too. “Somebody made the point that Dan Scavino will make for the entire year the cost of Brad’s one car, and it really pissed him off,” the second senior White House official said. Scavino, one of Trump’s longest-serving aides, is the White House social-media director, earning a government salary of $183,000 (the maximum for West Wing aides). Parscale, as the Lincoln Project so effectively noted in its ad, owns a Range Rover (starting at $90,000) and a Ferrari (starting at $200,000). “It was a really stark illustration to the president,” the second senior White House official said.

On the evening of July 15, Trump announced his decision: Parscale would be demoted and replaced as campaign manager by Bill Stepien, his former White House political director.

In the weeks that followed, Stepien was described to me by multiple members of the staff as a professional guy who cared only about winning the election — as though the arrival of a campaign manager who cared about winning was a notable development for a campaign on track to lose. “There are more corporate expectations of clocking in and clocking out,” a person close to the campaign and the White House told me. “Overnight, the expectations changed. One week people are being sent home because of covid, the next week it’s like, ‘Be in at 7 a.m.!’ A lot of people felt it was too harsh in the beginning.”

The morning after the deal was done, Parscale arrived at Trump headquarters. The staff crowded around as he recalled the earliest days of the campaign, when he said it was just him and five others working out of the basement of the Republican National Committee. Parscale became emotional — “choked up,” as one campaign official put it — scanning the roomful of faces he’d hired to build an operation he said he was proud of. He said he knew that Stepien would lead the team over the finish line but that — despite what the press was reporting — he wasn’t going anywhere.

“And then he literally just walked right out the door,” the campaign official said with a laugh.

Some people heard he went straight to the airport — which he did, going home to Florida, as much an effort at sanity preservation as it was a courtesy to Stepien, who he feared wouldn’t be able to assert himself while he was hanging around, hanging over him. A few hours later, he tweeted a Bible verse: “Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them.”

“Haven’t seen him since!” the campaign official said. “We didn’t hardly see him before, either. But now we don’t see him at all.”

There’s no other way to look at the demotion of Brad other than as a pushback of Jared as well,” the senior White House official said. (The portrait of the campaign in this story is based on interviews with more than 30 sources from the 2020 campaign and the 2016 campaign, Republicans in politics and government at all levels, and people who serve in the highest ranks of the Trump administration.)

Anyone with power or obvious ambitions to obtain it necessarily has rivals in Trumpworld. And Parscale’s close relationship with the president’s son-in-law meant he assumed the role of mark for Jared Kushner’s many haters. From Parscale’s perspective, there was an entire community of people on the outside who seemed to spend every day, every hour, every second vibrating with contempt for people — like him — who had real influence and real relationships with the people who actually mattered. Parscale spoke often to the president and considered him a friend, which, he understood, bred resentment. He tried not to engage with what he saw as dirty fighting — swampy stuff from the very crowd who had said they would drain it — in the belief that karma would have its say in the end.

Parscale’s value, as some saw it, lay not in what he could do for the campaign but in what he could do for Kushner. “Brad was willing to do whatever Jared said and keep quiet about it. Brad was willing to get yelled at by the president and not say to the president, ‘Well, actually, this was Jared’s decision,’ ” the first senior White House official said. “And Jared got to rule from afar because Brad would do whatever he said. In return, Brad made a fuck-ton of money and got to live by the pool in Florida. It was almost like this weird mutual partnership, whether they knew it or not.”

This way of thinking is so pervasive that sometimes, when I’m having a bad day, I wonder if it’s Jared Kushner’s fault. In the case of the reelection campaign, what appeared to be a civil war at the highest levels of Trumpworld, with anti-Kushner factions inside and immediately surrounding the West Wing positioned against representatives of his interests at campaign headquarters, and a last-minute last chance for a reboot before November, was more like WrestleMania. The drama was both all-consuming and self-contained. Parscale and Stepien were both seen as Kushner allies, yet the regime change was nevertheless regarded as revealing some aspect of Kushner’s shifting status — even as he remained functionally in charge the whole time. Kushner’s influence is so total that, even when his proxy is removed, he’s just replaced by yet another proxy. After all, if you’re not a “Kushner guy,” the dismissive term for officials perceived to carry out his will, what kind of guy could you even be?

This Kushner Kremlinology helps explain — though really, probably, only helps, since you’d imagine interpersonal details are ultimately trivial office gossip compared with the actual state of the reelection and what those working on it believe needs to be done to win it — why so many people on the campaign were so focused, in the reporting of this story, on pushing one narrative or another about exactly who was in the room when Parscale was fired. Depending on whom you ask, the meeting at which Trump offered Stepien the job was either kept secret from Kushner, who learned about it only after the deal was done, or orchestrated by Kushner, who urged the president to make the deal in the first place. (Two sources independently volunteered that Kushner was not in the room with Trump and Stepien, while two other sources, who coordinated, said he was. Nobody who anonymously provided information about the meeting to New York would go on the record to dispute their anonymous colleagues or provide corroborating evidence to support their own anonymous claims about this minor detail. All of these people are close to the most powerful man in the world. Are you surprised?)

“I do think it’s shitty that people are out trying to make Brad look bad to make themselves look better,” the source close to the White House and the campaign said. “We’re supposed to be all on the same team.” This person added, “It’s always this unspoken thing. Everybody knows who’s saying and doing things. So that’s really the shady thing. Like, Don’t do your dirty work in the media. Don’t be a coward. But eventually, these people show themselves, and karma’s a bitch.” Parscale, and those who liked him, believed it was Kellyanne Conway who wanted him gone the most. During the 2016 campaign, Conway made no secret that she was annoyed by Parscale’s folksy habit of announcing, to outsiders, that he didn’t know much about politics — and annoyed, too, that he didn’t know much about politics. “It’s charming that Donald Trump has never been in politics before,” she told him once. “It’s not charming that the people who work for him have never worked in politics before.” Parscale thought Conway wanted to take control of the 2020 campaign and that to do so, she needed to prove to the president that Kushner was fucking everything up, and that to do that, she needed to sabotage him. Trump was aware that Parscale saw Conway this way, but Trump also seemed terrified of Conway and never at risk of doing anything to intervene. For reasons Parscale could only speculate about, Conway’s job was always safe. (Conway thought the allegation was ridiculous and that if Brad had focused as much on Michigan and messaging as he did on nonexistent infighting, things might be a little bit different. As she saw it, Parscale’s demotion came after he tried to deny what the president saw with his own eyes — crowd size in Tulsa, the profligate spending, and the polls showing Biden ahead.)

It was Kushner who managed to calm his father-in-law down after the Tulsa disaster, according to a senior White House official, though he’d been the one promoting the rally as a campaign reset for weeks. Kushner told Trump that things were “going to be okay” and dismissed the crisis as “not a big deal,” according to the official. “Jared was pushing these rallies until Tulsa — and then, suddenly, it’s Brad’s fault.”

But Kushner’s intentions and the nature of his role were often willfully misunderstood by staffers who observed a limited percentage of his interactions with the president, according to a senior administration official. “The president always wants to hold rallies. He didn’t need encouragement,” this person said, adding that it was Kushner who got through to the president by explaining the issue to him in these terms: If no professional sports leagues were holding big events, the campaign had to rethink doing so too.

Looking back, Parscale wished he’d been able to stop the Tulsa rally, widely understood to have been his project — to tell the president it was a fucking terrible idea. But getting through to Trump was not easy. The president’s wings had been clipped by the pandemic, and no regular rallies meant no regular contact with crowds, which meant no way for him to know for sure that he had a feel of things. More than numbers, internal or external, he relied on his intuition, a sixth sense of sorts — a short finger not only on the pulse but on the beating heart itself — that made him an entertainer before it made him president. In 2016, one campaign official told me that this was how decisions were made, with orders that started with the words, “I feel like this is where we should go. I’m hearing this out there. Let’s do it that way.” Miller, a senior adviser to the campaign, said that he is in almost constant contact with Trump as Election Day nears, and that one of the things Trump most reliably asks about is “what the supporters are doing, what the activity is around the country, what the on-the-ground feel is for how the race is going — in particular, juxtaposed by the public perception of how the race is going.” Parscale felt pressured to give him what he wanted, so he did.

The shopping mall on Paxton Church Road was deserted. Pugliese Brothers (Authentic Italian Sausage), Enviro-Master Services (We Kill the Germs That Kill Your Business!), Sports Paradise (Team Sales Volume Discounts), O.C. Canvas Studio (Canvas Prints • Photo Prints • Art Prints • Custom Prints), Bagel Lovers (Cafe), and Little Owls Knit Shop were all closed. There were just two small signs of life: a half-blinking neon open on the otherwise dark façade of Grace Massage (somewhat suggestively advertised) and the fluorescent lights peeking through the collage of campaign banners in the window of the Dauphin County Republican Committee headquarters.

This was Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. I was looking for the ground game. Have you heard about it? The campaign says it’s the greatest ground game to ever exist, that while you don’t see enthusiasm for the president reflected in the rigged polls, you do see it when you talk to his real supporters where they live in Real America. In fact, they talk about surveys of enthusiasm not just as though they are more reliable than real polls but as though they are the polls — as though the traditional kind simply don’t exist, or matter. I drove across the country last month, and I saw only two signs for Joe Biden the entire way. Is this meaningful? The Trump campaign is hoping that it is. In Pennsylvania, they’re making calls and knocking on doors — a million a week — powered by more than 1.4 million volunteers. Pennsylvania is uniquely important. Rural voters won the state for Trump by less than one percentage point in the last election. This time, Trump is behind Biden by a lot. To close the gap, the campaign says it’s hosting dozens of events here — more than in any other state. But good luck finding them.

It was 7 p.m. on July 23, and Team Trump had scheduled a training session for campaign volunteers in the area. Before I arrived, I had worried about my exposure to the virus. I imagined a scene that was part local political-party headquarters and part anti-quarantine protest. I imagined a lot of Trump supporters, maskless and seated close together, breathing heavily on a reporter leaning in to record their comments. But the office was quiet. I walked through the arch of books by right-wing personalities (Bill O’Reilly, Sarah Palin, Ann Coulter, Glenn Beck, Rush Limbaugh) and past the portraits (George H.W. Bush, Ronald Reagan) and maps of Pennsylvania voting precincts. I didn’t see anyone there.

In a blue room in the back, beneath an American flag with the words MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN printed in block letters inside the white stripes, a woman sat alone at the end of a conference table. She wasn’t participating in the volunteer training. She was the volunteer training. There just weren’t any volunteers.

When she first thought I might be one, she was friendly. She offered me coffee and asked me to sit down. Two people had signed up for the Trump Leadership Initiative training, she said, but each of them had canceled, one citing an ear infection and the other citing allergies. When she learned I was a member of the media, her face hardened. She returned her gaze to her computer and told me she wasn’t permitted to speak to the press.

Fifty miles away, at the GOP headquarters in Lancaster, another event was scheduled for 6 p.m. the next night. When I arrived, the local field director, Jason, was talking to an elderly man. “I appreciate all your support, sir,” he said. “Oh, absolutely. I think this election is more important than 1864. Then, we would’ve lost half the country. This time? We could lose the whole country.” Nick, the Trump-Pence regional field director, asked me if I was there for the food drive — which was part of the campaign’s “Latino outreach effort,” he said — or the volunteer training. The elderly man had made his way out the door, and now there was nobody left in the office besides the two men who worked there. “There’s pretty light turnout,” Nick said. But not to worry, as things were “going really well,” Jason said.

A few days later, on July 30, the campaign scheduled two voter-contact training sessions at Convive Coffee Roastery on Providence Boulevard in Pittsburgh. The evening session was supposed to start at 7 p.m., but when I arrived, early, at 5:30, the shop had already been closed for half an hour. A girl cleaning up inside came out to talk to me (even when it’s open, like many such establishments, the pandemic rules are takeout only). She said she had no idea that any campaign had scheduled any kind of meeting at the place where she worked for two hours after closing time. But she hadn’t worked the morning shift that day, when the first event was scheduled, so she texted a co-worker who had. He told her a few people came into the shop and asked about a Trump-campaign meetup but that he didn’t know what they were talking about and couldn’t help them. “I don’t know if they figured it out or not,” she said.

I hung around for another hour waiting until eight to see if anyone showed. Nobody did.

A ten-minute drive away, at the second-floor county Republican committee office, some staffers — two young women and two youngish men — sat peering at their laptops, an enormous portrait of a scowling Trump behind them.

“What event?,” Kevin Tatulyan, an Allegheny County Republican official, asked as he waved me into the room.

“What event?,” Dallas McClintock, the regional Trump-Pence field director, asked.

One of the women, with lilac-colored hair, whipped her head toward McClintock.

“It’s your email here!” she told him, pointing to the advertisement I’d mentioned.

“My email?,” McClintock said in disbelief.

“Yeah!” she said.

He scrunched up his face.

For the next several minutes, the staffers tried to sort out how, with fewer than 100 days until the election, they had unknowingly advertised official campaign events that didn’t exist to potential campaign volunteers in the most important swing state in the country.

They squinted at their screens and asked questions.

“What time?”

“Where did you learn about it?”

“What was the address?”

The second event had been listed with an apparent misspelling in the street name, a detail that prompted the girl with the lilac hair to laugh.

“Sounds right,” she said dryly.

“I’m sorry!” the other woman said, and she seemed to mean it. “If you want to leave us your card, we can make sure to invite you to our events in the future!”

The night that he became the president’s campaign manager, Bill Stepien didn’t sleep much. There are people who work in politics because they are true believers in a cause or a candidate. Others are drawn by a childlike deference to, or need to be accepted by, authority figures. And others come for the status it confers, the way that office space near the arena can feel like an arena itself. Stepien is not that complicated. He just wants to win.

He faces an uphill path to get there, and doing so will require convincing enough Americans that Trump has “made a lot of really good decisions,” despite all the evidence that says otherwise, as the president told me at a Rose Garden press conference at the height of the pandemic this spring. (“So yeah, we’ve lost a lot of people, but if you look at what original projections were, 2.2 million, we’re probably heading to 60,000, 70,000.” Since then, at least 100,000 more Americans have died.)

Can Stepien make that case? With sandy hair and a vampiric complexion, Stepien looks too young to be a veteran of much more than the Boy Scouts. (After he was promoted, Fox News’ Greg Gutfeld jokingly congratulated the Trump campaign for hiring teenagers.) But at 42 years old, he has been in politics for more than half his life.

People who know Stepien tend to use the phrases “intensely private” and “hard to read” when they discuss him. He is the anti–Brad Parscale, according to officials who have worked with both men: “linear” instead of “scatterbrained,” deliberate rather than emotional, and — most of all — uncomfortable with the spotlight. Parscale seemed to seek public glory, and even when he wasn’t being photographed for magazines or speaking to authors, he was accused of trying to influence his media coverage with anonymous leaks. “Brad’s quotes are six-foot-eight and they’re bearded,” a senior White House official told me. “They’re obvious.” At five-foot-eight, Stepien literally takes up a full foot less space in the world.

To the extent that anyone had thought about it, the story of Bill Stepien was that of a talented political operative squished by scandal just as he was headed for the big leagues. Stepien ran his first campaign in 2002, an intraparty convention race for a local office. His candidate lost. He ran his next campaign in 2003, a New Jersey State Assembly race in the competitive 14th District, for his friend Bill Baroni. On Election Night, as the numbers came in, the win looked decisive for Stepien’s slate of candidates. But something had gone wrong with the math while he was tallying the votes for Baroni’s running mate, a former journalist named Sidna Mitchell. “Bill Stepien screwed the numbers up,” a person who worked with him in New Jersey politics said. “Stepien thought Sidna was ahead by 500, 900 — something like that. He had Sidna go and declare victory.” Mitchell is 79 years old now, but she still remembers that night in 2003. “I was told I had won — I think by, like, 500 points — and to make the victory speech,” Mitchell told me. The next day, Stepien had to inform his candidate that she hadn’t actually won. But State Assembly races being what they are, nobody cared much about this incident, and Stepien kept moving up — George W. Bush in ’04; then to the RNC; Rudy Giuliani in ’08; then, when that didn’t work out, John McCain. In 2009, he ran Chris Christie’s gubernatorial campaign and his reelection after that.

Republicans talk about “the Bob Franks school of politics” — or at least in New Jersey they do. Franks was a congressman, and Stepien had been his driver when he ran, unsuccessfully, for the U.S. Senate in 2000. “Bill Stepien learned about politics from Bob Franks,” one person who worked with Stepien on campaigns in New Jersey told me. “Bob had these rules: ‘Which message to which group of voters gives you 50 percent plus one?’ Bill learned politics that way.”

Stepien, once a part-time Zamboni driver who played forward for the Rutgers Scarlet Knights — “Pretty good on the puck,” said Sean Spiller, now the mayor of Montclair, who remembered winning a championship with Stepien — thought campaigns looked fun, like a sport. A second person who worked with Stepien in New Jersey said the experience taught him an unexpected lesson about how to find the best operatives: “Only hire hockey players, because they beat the crap out of some guy they don’t know just because it’s part of some game they’re playing.”

His beliefs were besides the point: “He didn’t care if every Republican in the state lost — as long as his guy won. He was a Republican by virtue of his environment. He held the right in considerable disdain. I would say he was fairly centrist — but he wasn’t driven by ideology. He never was. Politics was a sport for him. Had his first opportunity been to work for a Democrat, he’d be a Democrat.”

But while replacing Parscale with Stepien has the look of a reboot, at the strategy level it does not seem much has changed or is likely to. Asked how the campaign can formulate a coherent message, given what life is like for most people across the country today, senior adviser Jason Miller said, “It’s very direct: President Trump built the greatest economy in the history of the world, and he’s doing it again.”

But what about the polls? “I’d push back on that,” Miller said. “I have much more timely data, and much more accurate data, than what you have access to. And it’s improved over the last four weeks, and over the last two weeks, it definitely improved. We’re headed in the right direction.

“I feel much better about where we are in 2020 than where we were at this time in 2016. 2016 was brutal. We had Khizr Khan” — the father of Humayun Khan, a U.S. Army captain killed in Iraq in 2004, who criticized Trump during a speech at the Democratic National Convention — “we had Alicia Machado” — a former Miss Universe whom Trump ridiculed for gaining weight — “we had Judge Curiel kicking around somewhere” — a district judge who Trump alleged could not make impartial decisions concerning him owing to his Mexican heritage. “I feel much better,” Miller said.

By the third or fourth interview of the day in which a Trump campaign official argues, with what sounds like sincerity, that not only are the polls all wrong, they are wrong owing to intentional malpractice on the part of major polling institutions and their partnered major media outlets, and not only are they wrong but, actually, polls don’t even matter, because there is a silent majority of American voters who fear telling surveyors what they really believe and because the polls were wrong in 2016 (although they weren’t — national polling correlates to the national vote, not to the Electoral College, and Clinton won the popular vote by nearly 3 million, about what the polls indicated she’d win by, whatever the prediction models created by data journalists suggested), you begin to suspect you are the victim of something that’s not quite a conspiracy but more like a practical joke.

It’s not clear whether Stepien is in on it. Since his arrival, all the changes have appeared cosmetic, managerial, like the job was more office supervisor than chief strategist. He undertook a review of the campaign’s spending, he paused TV advertisements for a few days to sort out whether they were running in the right places, and so on. Asked to describe the way things are different now, campaign officials use strange jargon, referencing “org charts” and “building out middle management” and, above all, “structure.” Structure is the word they use the most. There’s more of it now, or something. This is supposed to be good, though not everyone feels that way. Some veterans of the 2016 race are wistful for what felt, to them, like the beautiful mess that made them who they were, winners against all odds. They didn’t know what they were doing, and there was an honesty to that, since it was kind of the whole pitch to voters.

“We’ve cleaned up — I don’t want to say the mess of — 2016. But we did things on the fly then. If you were like, ‘I wanna take a certain constituency on a bus tour around the country,’ they’d be like, ‘Sure!’ Now, there’s actually a strategy behind it,” a campaign official told me.

Having served as deputy campaign manager under Parscale, Stepien had observed the operation closely, and he had ideas about how to make things slightly better. He moved the countdown clock displaying the number of days until the election in front of the elevators so that it would be the first thing staffers saw when they arrived to work. He decided to give out an Employee of the Week award, something inspired by his political mentor, Mike DuHaime, who’d given out awards to his team when he ran Giuliani’s campaign in 2008. Stepien’s first Employee of the Week received a MAGA hat signed by Donald J. Trump himself. The employee was so moved by the honor that she cried.

With the exception of the time Vice-President Mike Pence came to visit, there had never been a meeting at HQ that included the entire staff — and Stepien noticed this. He is, you could say, the kind of guy who likes meetings. He planned to hold all-hands meetings every week for the rest of the campaign. The first would be the morning after his promotion was announced. Throughout the night, he thought about what he wanted to tell the staff, and he settled on this: Everything each of them was doing every minute of the day should be in the service of winning the vote. They should envision every day from now until Election Day as “a series of individual campaigns” and “to win every single day.” He said he would not tolerate being “outworked” by Biden’s campaign. “They may be more talented or better looking than us,” Stepien said, but they would not work harder.

“Is it a mess? Yeah. Everybody’s in chaos because there’s new leadership,” a senior White House official said. “But it’s like, ‘We’re all in this shitshow together right now! We really gotta make it work, guys.’ ”

If I just woke you up in the middle of the night and told you a guy who is deeply involved in Bridgegate is now calling himself campaign manager for Donald Trump, you wouldn’t have said, ‘You’re kidding me! I’m shocked. How did that happen?,’ ” Stuart Stevens said with a laugh. You’d have said, Of course.

Stevens is a veteran of Republican presidential campaigns whose latest book, It Was All a Lie, is about his newfound realization — at 67 years old — that his life’s work was a mistake. As he sees it, Trump has a “management philosophy” that has guided him from the Trump Organization to the 2016 campaign to the White House and now to the campaign for reelection. “What Trump does is take people who are mediocre talent at best, who know they could never have the position they have if it were not for Trump, and it creates this instant loyalty to Trump. When you look at Trumpworld, it’s all these people who weren’t involved in presidential races, and it wasn’t because they didn’t want to be; it was because nobody would hire them. It’s not like Steve Bannon woke up one day and said, ‘I think I’d like to get involved in campaigns!’ Or Corey Lewandowski, all of these people. It’s how you end up with Brad Parscale. Top professionals won’t work for you.”

The idea had always been for Bill Stepien to run a presidential race — but it was supposed to be Chris Christie’s. In the three years between Election Night in Asbury Park and Election Night in Trump Tower, however, all did not go as planned for the boss or his broker. It seems rather silly now, like a story about the Gotti family if they lived in Whoville, but the allegation that Christie ordered the closing of access lanes to the George Washington Bridge in order to exact revenge on a Democratic mayor who didn’t endorse him was such big news that it acquired its own gate.

To save himself, Christie fired who he had to — including Stepien, who had referred to the mayor of Fort Lee as “an idiot” in messages obtained by the press, and who most people who knew anything about his position suspected knew about the plot. Christie announced that he was “disturbed by the tone and behavior and attitude of callous indifference” shown by Stepien and that reading the messages “made me lose my confidence in Bill’s judgment.” Just two days earlier, he’d nominated Stepien to be chairman of the state party. Now, he said he had asked him to withdraw his name from consideration and to stop consulting for the RNC. “If I cannot trust someone’s judgment, I cannot ask others to do so, and I would not place him at the head of my political operation because of the lack of judgment that was shown in the emails that were revealed yesterday.”

But Christie wasn’t finished with Stepien. The following week, he hired a law firm to conduct an internal review of his administration’s role in the lane closures. At a press conference at the Park Avenue office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, Christie’s lawyer, Randy Mastro — a protégé of Giuliani — announced his findings with a 360-page report: His client was innocent, and Bridgegate was the fault of David Wildstein, an anonymous political blogger and Christie appointee at the Port Authority, and Bridget Anne Kelly, Christie’s deputy chief of staff. The report included a gratuitous disclosure: While working together, Kelly and Stepien “became personally involved,” but by the time of the lane closures, “their personal relationship had cooled, apparently at Stepien’s choice, and they largely stopped speaking.”

“The humiliation — being kicked to the curb and to be told someone lost faith in you — that hurt him,” a person close to the Christie administration told me. “Christie wasn’t just his boss; he was a friend. If you’re trusting and people hurt you, it’s almost like you’re used to it. But if you don’t let people in, I imagine it’s worse when they hurt you, and in trying to clean up his mess and not leave anything behind, Christie killed everything in his wake that could cause him harm.”

A second person close to the Christie administration said, “Christie just killed him. He didn’t even have the balls to call him.” Christie asked DuHaime to tell Stepien about his decision, this person said. “DuHaime brought Stepien to the dance. To make DuHaime do that was just awful.”

Under the belief that his idiot staffers cost him his shot at the White House, Christie “did everything he could” to “salt the earth” for them, ensuring they wouldn’t have political careers after they were fired, according to the second person close to the administration. “I can’t fault the guy for working for Trump. He’s gotta make a living. And it’s ironic, right? He ended up running a presidential campaign.” A senior official in the Trump administration said that when Kushner first tried to hire Stepien as field director during the 2016 Republican primary, Corey Lewandowski, who was then campaign manager, called Christie, who was still running for the nomination himself, and Christie helped Lewandowski convince Trump that Stepien was a bad idea, overruling Kushner. It was only later, when Lewandowski had been fired and Christie had dropped out and endorsed Trump, that Kushner was able to hire Stepien. (Lewandowski denies this happened, and another source involved in the discussions said that Christie never had anything bad to say about Stepien and never tried to prevent him from being hired by any campaign; but a third source with knowledge of the conversations affirmed the senior official’s account was “100 percent” true.)

“When he kicked Bill to the curb and ran everyone else over with the bus, he thought he’d finished Bill,” the first person close to the Christie administration said. “Jared had a huge role in bringing in Bill and trusting Bill for no other reason than he hates Christie too.”

Christie hadn’t fired Kushner or humiliated him by publicizing private details about his sex life — even worse, Christie had humiliated Kushner’s father. As the U.S. Attorney in 2004, Christie went after Charlie Kushner, a powerful real-estate developer and Democratic donor, in an investigation that would tear his family apart. Kushner pleaded guilty to 18 counts of illegal campaign contributions, tax evasion, and witness tampering (he’d retaliated against his brother-in-law, who was cooperating with investigators, by hiring a prostitute to seduce him, filming the encounter, then sending the tape to his sister. Pretty intricate and amazing stuff, if you ask me, and Charlie, if you’re reading this, I’d love to take you out for lunch). He was sentenced to two years in prison, of which he served 14 months in Montgomery, Alabama. Jared, then a student at NYU, flew to visit him every weekend, and for years after he got out, Jared reportedly used a wallet his dad had made him while he was inside.

“Bringing Bill into the Trump circle in 2016 was a slap in the face to Chris Christie,” one of the people close to the Christie administration said. “Like, ‘Okay, Christie, you’re irrelevant, and I’m gonna pick your guy who is no longer your guy.’ ”

“If they ended up in the afterlife together — though I’m confident they’re not going to the same place — Bill Stepien would still haunt Chris Christie,” said someone close to the Christie administration. “If Christie thinks Stepien is ever going to forgive him for what happened, then he doesn’t know Stepien. He never forgets. He never forgives. It’s why I’m not gonna be quoted in your story.”

People on the campaign say they believe — have to believe — there’s a way forward. If they just win North Carolina (where Trump leads by an average of one or two percentage points), Florida (where Biden leads by five), and Arizona (Biden by two), states Trump won in 2016, then they need only one state in the so-called blue wall of Pennsylvania (Biden by six or seven), Wisconsin (Biden by seven), and Michigan (Biden by seven or eight). These three states had gone Democratic in every presidential election since 1992 before Hillary Clinton lost them by 77,000 votes combined in 2016. Staffers assume that Ohio is already a Trump lock, although Biden is ahead there, too, by an average of more than two points.

“I don’t think we’re gonna lose this campaign,” said Bob Paduchik, Trump’s 2016 Ohio state director and a senior adviser to the 2020 campaign. “I don’t think we’re losing this campaign.” He told me the polling averages didn’t show Biden winning Ohio. I said that was wrong. Well, Paduchik said, the RealClearPolitics average didn’t show Biden winning. I told him that was wrong too — that I happened to be looking at that particular website as we spoke. Even Rasmussen, Trump’s preferred polling outfit, had Trump down by five, I said. “No,” Paduchik said, Rasmussen didn’t have a poll like that. When I said it sure did, that I was looking right at it, Paduchik said he couldn’t speak to that poll since he hadn’t reviewed it himself. Either way, he said, the polls were silly, based as they are on the premise that they measure how people would vote if the election were held today. “Well, the election is not today!” he said. “We haven’t had our debates and our convention yet. It’s sort of a fantasy guess.”

Seeing a path to Trump’s reelection doesn’t actually require fantasy. If the pandemic subsides, if the debates wound the challenger, if the polling narrows a bit, the hidden Trump voter — if such people exist — and the design of the Electoral College may be enough. If circumstances get slightly less bad, if the president forms a habit of making things worse a little less often, if he gets a little luck just one more time, he could pull this off again. Maybe Kanye West, or doubts about the official results of the election, or ratfucking the Postal Service, or birtherism directed at Kamala Harris is all the campaign strategy Trump needs.

But while Stepien has focused August ad spending in battleground states with early voting, effectively trying to stall the race long enough for the national picture to change, few on the campaign he’s running seem to be thinking in strategic terms at all, never mind enough to generate the kind of miracle the president needs. Instead, they seem to think that if they got lucky the last time, and proved the conventional wisdom wrong, maybe they’ll just happen to get lucky again.

And Trump does believe in luck — of course he does. “The president is superstitious,” one senior White House official told me, explaining why so many characters from 2016 seemed to suddenly come back for the final stretch of 2020. “I think what people miss about him is he’s more patient than he seems.”

*This article appears in the August 17, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!