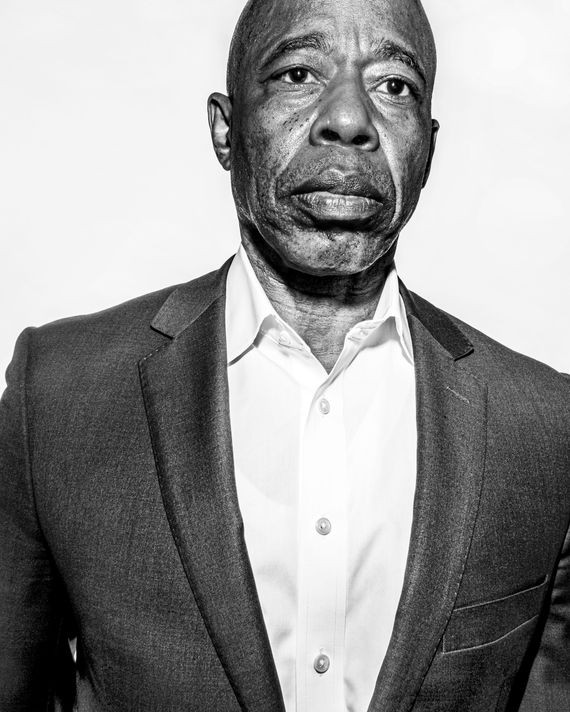

Heading into Memorial Day weekend, a poll had just shown Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams with his largest lead of the contest, and the mayoral candidates were spread out across the city, trying to catch up. Scott Stringer was down at One Police Plaza for a press conference on cutting bureaucratic bloat in the NYPD; Kathryn Garcia was in front of Moynihan Train Hall, rolling out a detailed plan for infrastructure projects in every borough. Maya Wiley was in Morningside Heights, pushing for the State Legislature to give victims of sexual abuse more time to sue, and Andrew Yang was in Tribeca, unveiling a proposal to help low-income seniors stay in their homes.

And Adams was in a park in Inwood, talking about dirt bikes.

By his side was Adriano Espaillat, the uptown U.S. representative and someone whose endorsement is one of the few in New York City politics that can actually move votes. Espaillat had been with Stringer before two-decade-old allegations of sexual harassment upended the city comptroller’s mayoral campaign. Before issuing his endorsement, Espaillat spoke with Adams about how dirt bikes and ATV’s were overrunning the streets, and here was the payoff: The congressman, surrounded by a half-dozen current and former uptown elected officials, singing the praises of a future Adams administration while Adams addressed a concern of his district.

The 2021 race for mayor is, as all political campaigns are, an experiment, an answer to the question of what kind of city New York is. Is it one that has taken a sharp left turn, highlighted by the rise of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and last summer’s racial-justice protests? (Based on recent polling, it seems decidedly not.) Is it one where municipal ties are so weak that someone who has never evinced much knowledge or even interest in city government can win based on cultivating a certain kind of internet fame? (Andrew Yang is hoping the answer is “yes.”)

Or is New York City still a town ruled by the same kind of party machines that controlled its governance for most of the 20th century: one of backroom deals, Brooklyn clubhouse politics, big real-estate money, and mutual back-scratching.

This is Eric Adams’s bet.

“This whole race has been about people trying to create different frames for it. Is it an ideological-left frame? A pragmatic-manager frame? A businessman-outsider frame?” said David Schleicher, a professor at Yale Law School and an expert in New York City politics. “But instead it is Eric Adams, building a coalition inside the shell of the Democratic Party of labor unions, Black homeowners, real-estate interests, and other Democratic Party politicians. If he pulls it off, he will be one of the most powerful mayors New York has had in a generation. It is the return of the permanent government, and Eric Adams is going to be at the center of it.”

Among the more than 30 former colleagues and staffers and current lobbyists, lawyers, and local elected officials who talked about Adams for this story — almost all of them anonymously, citing the fear that he would soon be mayor and look to exact revenge — most pointed to a moment from his first year in office as especially illustrative of how he would govern.

In 2007, Governor Eliot Spitzer demanded that state lawmakers receive raises only if they agreed to a series of reforms designed to clean up Albany’s cloudy way of doing business.

Adams, a Brooklyn native who had recently become a state senator after two decades in the NYPD, wasn’t having it.

“I don’t know how some of you are living to tell you the truth. With $79,000, you qualify for public assistance. This is a joke,” he said in a speech on the floor of the State Senate.

“We are not being paid enough,” he continued. “Don’t be insulted for yourselves. You should be insulted for your children, that you are not allowed to give your children an affordable, decent form of living.”

Politicians are not supposed to admit that they are interested in money for anything other than funding their campaigns. They are there to serve, after all. And they are especially not supposed to admit they are interested in money when they are making more than the median salary in the state for six months of work and their job comes with all sorts of perks, including per diems when they work in Albany. But Adams was willing to go there.

“I’ll be darned if I’m ashamed to say it,” he added, his voice echoing off the chamber walls. “I deserve to be paid more. And I’m only a freshman and I’m already complaining. We better vote on a raise and make sure we get paid more.”

The little speech became a headache for Democrats, who had been locked out of power for 40 years in the State Senate and were trying to retake the majority. Republicans jumped on the opportunity to cast a Black Democrat as gruff and greedy — especially the last part, when Adams turned to his colleagues and said, “Show me the money! Show me the money! That’s what this is all about! We deserve more money.”

Adams was a well-known figure in the city’s political scene before then, if an idiosyncratic one. To this day, those who know Adams describe him as deeply committed to racial justice. In 1995, he had started a group called 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care from his perch in the NYPD, pushing for Black and Latino officers to have more of a role in the department’s operations. He was described in New York Magazine in 1994 as a ”radical” and “contentious” transit cop, “[b]etter known for his strident, unaccommodating comments than for his leadership,” and someone who “seems always on the brink of inciting controversy,” such as when he criticized mayoral candidate Herman Badillo for marrying a Jewish woman instead of a Latina. He ran for Congress in 1994 against Representative Major Owens, a revered figure in central Brooklyn, on the grounds that Owens should never have denounced Louis Farrakhan. Adams lost.

He was investigated by the NYPD four times, once for traveling with other cops to Indiana to escort Mike Tyson from prison, violating the NYPD’s policy forbidding officers from associating with known felons. Despite being a self-described “conservative Republican,” he clashed with Mayor Rudy Giuliani in the 1990s over the mayor’s defense of the police in misconduct investigations. Four years after Giuliani left office, Adams would again find himself sparring with allies: This time, the police commissioner. While running for State Senate, the now-retired captain Adams appeared on television and cited his rank while voicing criticisms of the department. By repeatedly mentioning his rank, the commissioner at the time found, Adams had “imbued his claims and comments with the credibility derived from his official position and, in so doing could have confused, misled, and panicked viewers into believing that he was speaking on behalf of a department he had criticized and contradicted.” (“Those investigations were an attempt to disgrace him that failed—and they did not lead to any discipline aside from a wrist-slap for ‘appearing on television without permission,’” said Evan Thies, a spokesperson for Adams. “Eric was despised by the leadership of the NYPD for speaking out against police abuse and racism, and they targeted him and slandered him every chance they got.”)

Once in Albany, Adams developed a reputation as one of the most camera-ready, charismatic members of the State Senate. He helped lead the charge against the practice of stop and frisk in the Bloomberg era and worked on anti-gang and anti-gun initiatives. But he also made his colleagues cringe with embarrassment, like the time he started a campaign to get teenage boys to pull their pants up or released a PSA teaching parents how to search their children’s baby dolls for guns or drugs.

Adams had an eye for where the power centers were and knew what powerful politicians needed, but he also made some problematic associations. He developed a close friendship with Hiram Monserrate, another ex-cop with a devoted following in his district in Queens. Monserrate threw the state government into chaos in June 2009, when, along with fellow Democrat Pedro Espada, he bolted the conference and joined the Republicans in an attempt to shift control of the Senate.

Former colleagues of theirs said that Adams and Monserrate bonded over the fact that they were both former cops. After Monserrate was arrested in December 2008 for slashing his girlfriend in the face with a piece of glass, Adams claimed that police were railroading Monserrate because he, like Adams, had been a reformer inside the department. As State Senate Democrats debated what to do about Monserrate and launched a four-month investigation into the incident, behind closed doors Adams became one of his most vociferous defenders. “He was just so dismissive of the fact that any of us thought this was a serious issue,” one lawmaker said. “It made my skin crawl.”

When Democrats voted to expel Monserrate following his assault conviction in 2010, Adams walked out of their meeting. “Fuck all y’all,” he said, according to two lawmakers present. (Through his spokesperson, Adams strongly denied saying this and put me in touch with Diane Savino, another Democratic senator who said it never happened.) He later claimed that his opposition was on procedural grounds, writing in a letter to constituents that “I decry all domestic violence behavior; to condone violence against women would violate all standards of decency, run counter to my commitment to end domestic violence, and violate my core values!”; Adams later attended Monserrate’s wedding and a campaign birthday party in 2018, when Monserrate was mounting a political comeback after serving 21 months in prison on federal corruption charges. (Adams publicly broke with Monserrate in February of this year.)

Adams had a way of becoming the power behind the throne, getting close first to State Senate Democratic leader Malcolm Smith, then becoming a top lieutenant to the man who replaced Smith, John Sampson. “It’s odd to see him running for mayor because he was always the guy behind the guy,” said one State Senate Democrat.

Former colleagues remember Adams as constantly trying to play different angles. In 2013, the Republicans, who were responsible for making committee assignments and who had not a single Black member in their body, offered Adams and another Black Democrat, James Sanders, chairmanships of committees. Sanders declined, but Adams accepted, becoming chair of the Committee on the Aging. The role came with a salary boost, a bigger office, and access to donors. His fellow Democrats saw it as a sign that he would be with the GOP on tough votes, and when they approached him about the need for Democrats to maintain a united front, Adams was dismissive. “He just wasn’t a team player,” recalled one senior Senate aide. “In a way that’s true for everybody in politics, but you always got the sense that the thing Eric Adams cared most about was what was in it for Eric Adams.”

“There is a certain kind of New York politician for whom The Godfather is their favorite movie,” recalled one former colleague. “Eric Adams is one of those politicians.”

Although he never joined the group of breakaway Democrats who caucused with the Republicans known as the Independent Democratic Conference, he was seen as quietly supportive of them, and after he left the Senate, Adams was replaced by a former staffer who did promptly join the group. “We called him ‘Captain Chaos,’” one lawmaker said. Adams would also disappear for weeks at a time for foreign travel. He and Sampson traveled to South Korea with a high-powered Albany lobbyist and with staffers from their offices. (Later, as Brooklyn Borough President, he’d accept thousands of dollars in travel to China, Turkey, and Azerbaijan paid for by the host countries.)

The schemes could occasionally shade into something more serious than a lack of judgment. In 2010, Adams and Sampson were in charge of recommending which company should win a contract to open up a new casino at the Aqueduct racetrack in Queens. Sampson later admitted leaking an internal State Senate document assessing the bids to the company that later won the contract, AEG, while company representatives attended a Grand Havana Room fundraiser for Adams and donated to his campaign. Adams joined a company representative and Sampson and then-Governor David Paterson at a dinner but later denied that he was there, saying he just happened to be at the same restaurant and saw them there, something that a state inspector general wrote “strains credulity.” After recommending the contract to AEG, Adams later attended a victory celebration at the home of the company’s lobbyist, which the inspector general said “reflects, at a minimum, exceedingly poor judgment.” Adams continues to deny that his conduct was improper; his spokesperson called the inspector general’s report “a political hit piece.”

The saga led to Sampson’s getting booted from his position as Democratic leader in favor of Andrea Stewart-Cousins. Adams stayed by his side. Sampson at the time was under investigation for stealing $400,000 on the sale of foreclosed homes and asking a friendly prosecutor he knew to turn over the names of those who were testifying against him so he could “take them out.” But he still fought to hang on to his leadership post, and Adams was in charge of rallying Democratic lawmakers to support Sampson. Sampson refused to step aside, certain that Adams had procured him a majority. In the end, Democratic senators overthrew Sampson in a landslide, leading Adams to once again storm out of their conference meeting. “He doesn’t know how to operationalize anything,” one lawmaker present said.

Adams was treated with such suspicion by his fellow Democratic lawmakers that one senator, Shirley Huntley of Queens, started taping her conversations with him while she was under investigation for corruption, hoping that she could use them to stave off any jail time. Huntley was sentenced to a year in jail; she recently reappeared at the opening of Adams’s Queens campaign headquarters.

“He became the shadow leader of the conference when he was here,” said one lawmaker who served alongside Adams. “But I tried to stay away from him, and I think others did too. We always assumed he was wearing a wire.”

Adams remained in Albany until 2013, when he ran for Brooklyn borough president without any serious opposition. The post of borough president is a largely ceremonial job with some powers over land use but offers a straight line to City Hall for mayoral hopefuls. Adams wasn’t shy about his ambitions: He raised eyebrows when, soon after his inauguration day, he said he was going to run for mayor in eight years and set up a nonprofit, called the One Brooklyn Fund, where he could solicit donations outside the city’s strict campaign-finance system. While the organization has put on community events, it has also drawn concern from good government groups, who charge that its spending on galas and marketing materials have boosted Adams’s own political profile. Adams always had a penchant for making shocking statements — he once told a reporter that the only reason you used to see a white guy walking down Franklin Avenue in Crown Heights is if “he is into S&M and wants to get robbed.” As borough president, that streak continued. He told a group of LGBT seniors at an affordable-housing ribbon cutting that their place in the neighborhood was unwelcome and that it may provoke confrontations, and he told white gentrifiers that they should “go back to Iowa.”

Adams’s ascension in Brooklyn coincided with a low period for the Brooklyn Democratic Party. Home to more Democrats than any other place on earth, the party over the last decade has watched as party-backed candidates lost to ones supported by the left-leaning Working Families Party and Democratic Socialists of America. Adams has tended to buck parts of the political Establishment in the city, but he has remained loyal to the Kings County Democrats, and he grew close to Frank Carone, the party’s lawyer and someone who, over the past eight years, has become a top ally of Mayor de Blasio and quietly become one of the most influential power brokers in the city.

Carone has worked as the Democratic Party’s lawyer for years, and in 2012 he joined the law firm Abrams Fensterman, whose lawyers including Carone have given thousands of dollars in campaign contributions to Adams over the years. When Adams ran unopposed for Brooklyn borough president in 2013, it was in part because Carone, as his lawyer, helped kick his opponent off the ballot. Howard Fensterman, the founding partner of Abrams Fensterman, is a major fundraiser for both Andrew Cuomo and Chuck Schumer; the firm has spawned a series of ancillary businesses including nursing homes and consulting firms, and Fensterman once described the law practice as “the golden goose” and “a platform to launch us into other businesses.”

Both Carone and Adams grew to become close allies of de Blasio. When de Blasio was mired in his own state and federal investigations for illicit fundraising, Adams was one of his few defenders. When de Blasio ran for president, Carone enthusiastically raised money for him. “Bill de Blasio doesn’t really have friends,” said one former de Blasio staffer. “But to the extent he does, Frank Carone is one of them.” Carone regularly socializes with de Blasio, and former City Hall staffers said they knew to always take both Carone’s and Adams’s calls.

Their needs were different. Adams, who believes that veganism cured his diabetes and prevented him from going blind, would request meetings with top officials in the Health Department to talk about the importance of a plant-based diet and would complain that his longtime romantic partner, Tracey Collins, was being mistreated by her bosses at the Department of Education.

Carone, whom the Daily News described as having “unfettered access” to de Blasio, sent names and résumés to a de Blasio aide and messaged staffers directly to deal with issues his clients faced, according to emails obtained by the newspaper through a public-records request. Carone never registered as a lobbyist, but he quickly became the go-to lawyer for a number of controversial real-estate developers. Carone has represented the Allure Group, which bought the Rivington House, a former medical facility for HIV patients, and sold it to luxury real-estate developers, a deal that plagued de Blasio throughout his first term and led to an attorney general’s investigation. He has represented the developers behind the plan to close Long Island College Hospital and replace it with seven luxury towers. Readers may recall that de Blasio was arrested as a candidate to prevent this plan from going through; Adams hosted several meetings on the plan, and it was the most engaged many elected officials recall seeing him. “I couldn’t believe it,” said one local official. “He wouldn’t return any of our calls about anything, but this was the thing he cared about?” Observers couldn’t help but note that, in the end, de Blasio ended up on the same side as Carone.

Carone and his firm have also represented a Brooklyn developer who had to pay out a $3.4 million settlement for evicting seniors from a nursing home and the Podolsky brothers, who despite pleading guilty to dozens of felonies for their treatment of tenants, recently sold $173 million worth of real estate to the city, a figure that is by some estimation three to four times what the properties were worth.

According to another exposé in the Daily News by Michael Gartland, who has tracked Carone’s rise closely, Carone’s wife has benefited as well, getting paid $100,000 to host party fundraisers even as the party’s finances have been devastated, its cash reserves dwindling from $500,000 the year Frank Seddio took control of the party to just $32,800 in 2019.

Throughout the campaign, Adams has done Zoom forums at Carone’s office and works out of his firm’s office. The prospect of an Adams mayoralty has worried many people who know both of Adams and Carone well. “Carone is using his position within the party to essentially advance Adams,” said Theodore Hamm, a professor at St. Joseph’s College who has followed the Brooklyn Democratic Party closely for the left-leaning Indypendent. “If Adams wins, given his track record, Carone will have a lot of influence as the point man for doing business with the Adams administration. He personally stands to gain immensely.” Adams has a history of bending to the demands of his backers: In 2018, for example, he abruptly reversed course on ending the specialized exam for the city’s elite schools after facing backlash from his Chinese American donors. (“Eric’s position on specialized schools has nothing to do with contributors to his campaign,” said spokesperson Thies.)

Carone has been quietly making calls on Adams’s behalf, especially among real-estate interests and ultra-Orthodox Jews. Carone was bundling for Scott Stringer back in 2018, when it seemed as if Stringer was a frontrunner to be the next mayor; Adams’s rivals say he may now be fundraising for Adams instead. (“He makes calls to his friends and family to encourage them to vote for Eric and will continue to do so,” said a spokesperson for Carone, but “he does not bundle.”) He can be charming, people who know him say, a kind of Mill Basin version of Manhattan PR maven Howard Rubenstein with a threatening streak like Joe Percoco, the Cuomo former aide who developed a reputation as the governor’s enforcer and who is now serving time in federal prison. Multiple lawmakers told me that if they endorsed another candidate besides Adams, they received cryptic text messages from Carone soon after, featuring, say, a simple question mark, or a screenshot of the announcement with nothing more added.

Adams’s rise is boosting Carone, too. “He has used politics to build his law practice, then used his law practice to build a political organization. It’s the oldest story of machine politics there is,” said one city councilmember. “He bet big on Bill de Blasio, and he bet big on Eric Adams, and both of those bets look like they are going to pay off spectacularly.”

That same morning Eric Adams appeared in the park in Inwood, he didn’t know that he had another person with him, an opposition researcher for the Andrew Yang campaign. Adams’s rivals had grown frustrated that Adams seemed to be constantly unveiling new parts of his biography and had for weeks been devoting considerable resources to trying to catch Adams in a lie. At a campaign stop on June 1, for example, Adams said that he had spent time at the notorious Spofford Juvenile Detention Center in the Bronx, something he had not mentioned previously, although he did say in his campaign launch video that his mother picked him up from the precinct house when he was arrested at the age of 15. He said he worked for a time as a squeegee man. He said in the first mayoral debate in May that as an off-duty police officer, he stopped an anti-Asian hate crime in process and also that he shot a knife-wielding assailant. He said that when he returned home from the hospital after his son was born, enemies of his in the NYPD drove by and shot out the windows of his car. There’s no evidence that these things are not true, but his opponents are suspicious, whispering that the narrative pieces have fallen in place too conveniently.

Recently, focus fell squarely on a simple question: Where does Adams live? Sally Goldenberg, a reporter for Politico, started dropping by Borough Hall late at night, noticing that the lights were on and that Adams’s car was there. The Yang camp has had as many as four operatives on duty staking out Adams’s various homes and his office. So far they have found that he stays at the office into the wee hours of the morning and have seen no evidence that he returns home to any of the Brooklyn domiciles. There have been a couple of tense moments when Adams seemingly recognized the Yang tails. On one occasion, he rolled down his car window and smiled and waved theatrically.

When I first began covering this race, I would talk to the various operatives about their plans and strategies, but at some point it all seemed kind of silly: Even seven months out, Eric Adams was the odds-on favorite to be the next mayor of the City of New York. The candidate favored by a plurality of Black New Yorkers has a tremendous advantage in a Democratic primary, where voters of color make up a majority. This was de Blasio’s path in 2013, when he campaigned relentlessly in central Brooklyn with his Black son, and it was Bill Thompson’s path before that, and Fernando Ferrer’s before that. Adams has added to that support by getting the bulk of the city’s major labor unions behind him, often with de Blasio’s blessing.

It is a bit of a good-cop-bad-cop routine. People who worked and served with Adams, and who told me that they would seriously consider leaving the city if he won, still say that he is an immensely talented politician — charming, personable, charismatic — and that he tends to not hold grudges or obsess over slights. His campaign has been a bare-bones operation, and he has scarcely spent any money as we head into the race’s final days, leading his rivals to wonder what he actually intends to do with what will remain of the more than $10 million he has raised, more than any of his rivals who are participating in the taxpayer-backed city campaign-finance system.

It is hard to predict what the story of the Adams campaign, and potential administration, will be. His path to victory resembles a race-flipped version of Ed Koch’s in the 1970s and ’80s, putting together a working-class outer-borough coalition buoyed by middle-class homeowners. It is the pre-gentrified, pre-Bloombergian way of winning. And if he pulls it off, Adams would be the mayor of labor and communities of color. With this coalition, Adams could get more out of Albany than any mayor before him. He would be free to ignore his detractors among the mostly white left-wing activists in the city, who made it clear they were never with him in the first place. An Adams administration is likely to view the city’s issues through a racial justice lens, arguing that equity can’t be achieved if streets aren’t clean, or government operations run efficiently, or schools aren’t better. Although he has been criticized for some of his comments and causes, from his remarks at the LGBT center to his “Stop the Sag” efforts, his campaign believes that such messages are heard differently in working class communities, where voters feel like Adams is the only one who understands them and has the courage to say what they are thinking. He has accused his opponents and the press of playing into racist stereotypes, most recently comparing investigations into where he lives to Birther attacks on President Obama.

“If you think New York politics is not enough about ideas, or is too transactional as it is, or no one cares for the broader city interest, you are really going to not be happy with an Adams administration,” said David Schleicher, the Yale Law professor. “In a multivalent, decentralized city, someone who is backed by labor and the Post and the police and by middle-class homeowners is going to be able to achieve pretty much what they want, and everyone else is going to be terrified of him.”

He quoted George Plunkitt, the leader of the Tammany Hall at the turn of the century, who once said of the reformers who challenged Tammany’s rule that “they were mornin’ glories — looked lovely in the mornin’ and withered up in a short time, while the regular machines went on flourishin’ forever, like fine old oaks.”

More on the NYC Mayoral Race

- Free the Trump Trial Transcripts

- On Patrol With the New York City Rat Czar

- Earthquake and Aftershock Shake New York City: Live Updates