On a Sunday in April, Gregory Meeks, the head of the Queens County Democratic Party and the congressman from the largely Black, middle-class, home-owning precincts of southeastern Queens, endorsed the mayoral campaign of Ray McGuire, a former Citigroup executive whose candidacy has been buoyed by a biography that takes him from the other side of the tracks in Dayton, Ohio, to a position as one of the highest-ranking Black executives on Wall Street.

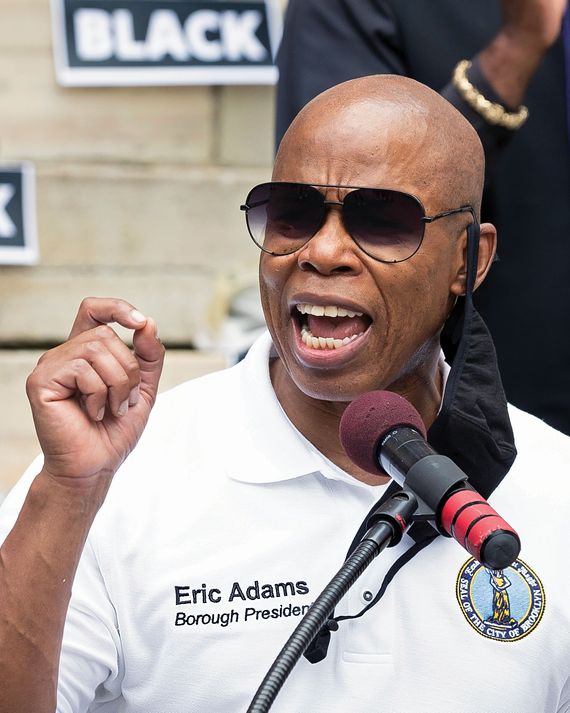

So one day later, Eric Adams, the Brooklyn borough president and a leading candidate in the mayor’s race, came to southeastern Queens himself to open a campaign office. Stepping up to the microphone at the ribbon-cutting on April 19, Adams made clear that his is no rags-to-riches, Dayton-to-downtown story.

“I am you. You all finally have a candidate that is you,” he said to the crowd. “I have always been here.”

Adams headed inside, where the room echoed with volunteers reading from the call script: “Eric is the only blue-collar candidate in the race and has lived his whole life right here.” He made his way to a table in the back, where an aide brought him a green juice and a bean salad. Adams credits switching to a plant-based diet with reversing his type-2 diabetes, which had briefly rendered him partially blind; he lost 35 pounds and wrote a book called Healthy at Last. Lawmakers and lobbyists have told me it is the subject that seems to animate him the most.

Adams was a cop for 22 years before entering politics. He started talking about running for mayor almost immediately after he was sworn in as borough president, telling reporters it would be hypocritical of him to speak at school graduations and say to young people that they could be whatever they wanted if he were denying that he wanted to be mayor. He now has a long list of labor-union endorsements and the most money on hand of anyone in the race. Adams is an affable presence on the trail, a glad-hander with a booming laugh who gives out his personal cell-phone number to people he wants to talk more with (when I was with him, this included someone who wants the city to fund centers for kids to play video games after school). But Adams is also a political pugilist who hit the heavy bag at Gleason’s Gym to call for the return of indoor fitness classes and who has relentlessly attacked Andrew Yang as an arriviste, turning the sprawling field into a two-person race — and many city insiders are skeptical Yang can pull it off. When I asked staffers of rival campaigns who they thought was going to be the next mayor of New York (if, somehow, their candidate didn’t win), most said not Yang but Adams.

Although New York remains far safer than it was in the days when he was patrolling its streets and subways, Adams’s emergence has coincided with a dramatic uptick in gun violence. The day after we spoke, Mayor de Blasio announced plans for a new police precinct in southeastern Queens. Residents had been calling for one for years, citing slow response times, but the project was shelved last summer due to NYPD budget cuts in a heated political climate. Now, the mayor is reversing course.

Adams told me he first heard the phrase “defund the police” at a march over the summer protesting the murder of George Floyd. As he tells it, a young Black man, prodded by a group of his white friends, came up to Adams and confronted him, demanding he join their calls to defund.

Adams pointed at the protester’s friends.

“They are not living in the community that you are living in,” Adams told him. “Go back to your community, where there is real violence, and tell me you still want to defund the police.”

As a teenager, Adams was beaten up by police in the basement of a South Jamaica precinct house; as a cop, he co-founded a group called 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care, which advocated for improved relationships between police and communities of color. That tension, between being a police officer and being aware of police abuses, remains unresolved in Adams. Last year, for instance, the NYPD moved to disband its notorious anti-crime unit, which had been charged with getting guns off streets and was responsible for a disproportionate number of fatal police shootings; Adams wants to see the unit reinstated. He testified against stop and frisk as a state senator but now wants to bring back a modified form of it. He was at first against closing the prison at Rikers but now is in favor of doing so. He says pimps and johns should be prosecuted but does not want to decriminalize prostitution.

“You can have all the reforms you want. You can have a kinder, gentler police department. But if your streets are filled with guns and you’re dealing with a lot of violence, you are still going to have a lot of children being shot,” he said.

Yet he added, “If you are an innocent child and all you are doing is going to basketball practice and some cop stops and searches you, you are not going to go to that cop and say, ‘Listen, there’s a person that is carrying a gun; there’s a person that is selling drugs.’ If you erode that trust, you are going to erode public safety. Many of my opponents are really ignoring the public-safety part of it, and I refuse to do that.”

Adams says cops should go into the schools not just when there is a problem but to sell students on careers in law enforcement. (One of the reasons Adams is against defunding the NYPD is that, because of seniority rules, it will mean fewer jobs for women and people of color in the department, which he and his allies fought for years to diversify.) They should take students to the airfield where the police helicopters are parked and coach them in basketball, boxing, or dance, in what he says would be a proactive approach to steering kids away from a life of crime.

All this can sound like a remnant of the 1990s, when midnight-basketball leagues were proposed as the solution to nearly any social ill. The internet recently unearthed a decade-old video in which Adams tells parents how to search their homes for the drugs and weapons their teens may be hiding. He pulls a crack pipe out of a backpack, bullets from behind a picture frame, and marijuana from the innards of a doll. One year earlier, he had addressed the scourge of young men wearing baggy pants by paying for a half-dozen billboards showing photos of offenders and the phrase STOP THE SAG.

“You can look and say, ‘Okay, Eric took a controversial position,’ but now you don’t see the problem everywhere you go,” he told me. “Everyone saw it, but no one was bold enough to talk about it.”

Adams’s campaign pitch is, in a lot of ways, similar to the one that propelled Joe Biden to the presidency. It is predicated on the belief that most of the Democratic electorate isn’t on Twitter. Like Biden, Adams’s theoretical winning coalition is Black and Hispanic voters combined with those working-class whites, small-business owners, and even Manhattan financial types who feel he can stave off the city’s leftward drift.

Voters like Joe Jackson, a 77-year-old Queens resident who retired after 39 years of working for New York City Transit. He had come to make calls on the candidate’s behalf and was wearing a BLACK LIVES MATTER baseball cap. Calling Adams a police officer but “one of the good guys,” he said neighborhoods like his should have more police, not less: “People feel safer.”

Back when Adams was trying to reform the police department from the inside, the call to curb cops’ worst excesses came from neighborhoods like this one. No longer, Adams says: “Now, this is really being led by a different demographic. There are a lot of young white affluent people who are coming in and setting the conversation.”

The New York Times, he noted, may run an op-ed with the headline “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police,” but the paper has police officers in its lobby. “When you start defunding, hey, the cop is no longer on your corner. That cop is no longer in your lobby. That cop is not standing outside when you leave your Broadway play. And I have never been to an event where the people were saying we want less cops. Never.”

More on the NYC Mayoral Race

- Free the Trump Trial Transcripts

- On Patrol With the New York City Rat Czar

- Earthquake and Aftershock Shake New York City: Live Updates