This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Kate was gardening in the front yard of her San Jose bungalow when her new boarder arrived in an Uber from the airport. It was the summer of 2019, a few weeks before classes were set to begin at nearby Santa Clara University. A friend who worked there had asked if she would rent out her guest room to a new adjunct sociology professor. Kate had Googled the name — Dr. Gary Maynard — and found his academic profile impressive. “He’s good-looking,” she says. “That didn’t hurt.”

Maynard, wearing a preppy polo and tattered sneakers, stepped out of the car with a heavy book bag. He was 45 with a lanky build, floppy hair, and a shambling demeanor. Kate showed her new roommate around the house. He seemed twitchy and anxious, and he left after just a few minutes, mumbling something about researching homelessness in San Francisco. Maynard didn’t return until the next day. “He just disappeared,” Kate says. “It was a little odd.” Coming from a sociologist, it was a surprisingly antisocial introduction, but Kate wrote it off as eccentricity — maybe it was to be expected from a professor. She figured that Santa Clara, where tuition runs to over $56,000 a year, would have done its homework on anyone it hired. The university had given Maynard a one-year contract to teach a variety of subjects, including the cultural effects of technology, organizational diversity, and the sociology of crime.

Kate, who is in her mid-50s, found she enjoyed Maynard’s company once he settled in. She worked as a court reporter, transcribing depositions all day, and was going through a divorce. (She asked to be identified by her first name only.) At dinner, she would pull a bottle from her wine rack. Maynard didn’t drink much, but he smoked weed. Besides his Ph.D. in sociology, he had master’s degrees in political science and theater history. “He has an air of authority,” Kate says. “It is a sight to behold.” He studied social deviance and was interested in cults, conspiracy theories, and the paranormal. He was rapturous about nature and spoke of his empathic connection to trees. They commiserated about their hatred of Donald Trump, going deep down all the resistance rabbit holes. “We would sit across the table and talk for hours,” Kate says. “I was just soaking it in.”

Much of Maynard’s work was related to the dynamics of life at the margins of society. His interest in precarity, to use the trendy academic term, wasn’t just intellectual. As an adjunct, he was what is known as a contingent faculty member: a journeyman, moving from job to job, earning as little as a few thousand dollars per course at whatever institution needed a teacher to fill in for a semester or two. By the standards of the industry, though, he thought his situation at Santa Clara was pretty sweet. “My days there were a dream,” Maynard later recalled. He would pick mandarins from a tree in Kate’s yard and bike to the campus, which was built around an old Spanish mission. The department chair treated him with respect, giving him a shared office that looked onto a tree-lined quad. His students were engaged, and he said he found the classroom atmosphere “intellectually intoxicating.”

At Thanksgiving, Maynard had no place to go, so Kate invited him to celebrate with one of her friends. He spent a curious amount of time talking about the bloodlines of the British royal family. Kate drank too much. Maynard brought her home, drew a bath, and put her to bed. After that, the relationship turned romantic. Kate was still reeling from her divorce. “We were two lonely, hurt people that had found each other, right?” she says. “It was so thrilling.”

Kate got Maynard to try yoga. They lit candles around the tub and took long baths together. They would go out and do role-play, pretending to meet as strangers at a hotel bar. Like many in his field, Maynard was influenced by the sociologist Erving Goffman, who saw all the world as a stage on which people behave like actors, hiding their true selves behind masks. With Kate, Maynard let his mask slip. He confided that his life had been full of struggle and hurt. He said that he had an autism-spectrum disorder and that workplace relations were an ordeal. He would agonize for days before departmental meetings, gaming out where to sit and how to avoid notice.

That spring, the pandemic caused Santa Clara to shut its campus and shift classes online. At first, that wasn’t so bad for someone who craved isolation, but new stresses soon emerged. Kate could hear Maynard yelling to himself as he doomscrolled the news. In May, she returned from a vacation to discover Maynard had set up surveillance cameras inside her house. He turned inward, sealing himself up in his room, covering the windows to block the sun.

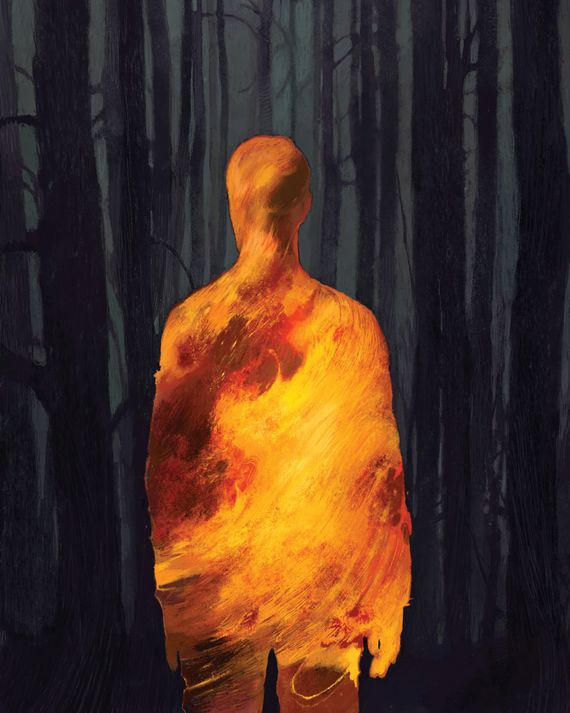

Then, that angry summer, California began to burn. The West was experiencing its worst drought in 1,200 years, with ideal conditions for wildfires. Flames consumed more than 4 million acres, an area half the size of Belgium. The sky over Kate’s house was dark during the day and glowed orange at night. It was as if the mind smoldering inside her spare room had taken on metaphysical form.

Kate begged Maynard to seek counseling. One night, he bashed up his room with a hammer, and afterward she told him he had to leave. A pandemic moratorium meant Kate couldn’t outright evict Maynard, and she still cared about him, so in the end she basically bribed him, giving him around $3,000 and a used Toyota SUV.

In September 2020, Maynard hit the road. He lived out of the car and continued to teach. He told me that no matter what others may imagine, he was content with his “beautiful life as a semi-homeless, partly employed sociology and criminology college professor.” He moved up and down the West Coast, giving long, free-associative lectures from anywhere his phone could pick up a signal: a co-working space, a motel room, a campsite in the forest. Because the classes were all online, it was easy for him to pick up a second job teaching criminal-justice courses at Sonoma State University. Freed from supervision and the walls of the classroom, he would sometimes tape material for his courses as he drove.

Maynard uploaded one such video to YouTube that November, narrating a sunset drive through the scorched landscape left by a recent wildfire in southern Oregon. “Look at the cars — they’re melted,” Maynard said as he panned his camera across the charred scene. The inferno, which destroyed 2,600 homes, had been attributed to arson. Investigators didn’t know who had committed the crime. (It is still unsolved.) “I’m just doing this for research, trying to analyze the environment,” Maynard said as he sat at a red light. As climate change made wildfires exponentially more dangerous, he said, there was an “emerging field” within criminology that sought to explain the arsonist mind-set.

“Who does this?” Maynard asked. “Why?”

Within a year, Maynard would be accused of becoming an arsonist himself. In August 2021, law-enforcement agents apprehended him in a remote wooded area of Northern California, where, authorities alleged, he had applied his expertise to setting what one federal prosecutor described as an “insanely dangerous” series of wildfires. None ended up causing much damage, but they occurred at the same time and in roughly the same area as the Dixie Fire, an accidental blaze that became one of the largest infernos in the history of the state. The tidy coincidence of Maynard’s academic specialty turned his case into national news. “Expert on Criminal Minds Is Accused of Wildfire Arson Spree,” read the front-page headline in the New York Times.

Since then, Maynard has been sitting in jail as he awaits trial. He has pleaded not guilty and contends that he has been miscast. He says he never could have committed such a senseless and destructive crime. He is a specialist in deviant behavior; he knows all the literature. “I’m a criminologist,” he told me. “I don’t fit the profile.”

Nobody in California has sympathy for an accused firebug. After Maynard’s arrest, he was held without bail at a county jail in Sacramento where the other inmates would make his life miserable, constantly trying to pick fights. He called the facility a “demonic hellhole.” Still, for a criminology scholar, incarceration had some intellectual consolations. “If I wasn’t in the middle of it, it would be fascinating,” he told me by phone in October.

Maynard said his lawyer, a federal public defender, had instructed him not to speak to the press; neither she nor any of Maynard’s family would comment for this article. But he was determined to defend his professional reputation. I’d first written to him after his arrest, and in the following months he would call at unpredictable moments, sometimes in the middle of the night. He sent me long handwritten letters trying to explain how he had ended up in the woods. “It is always very difficult to describe yourself, for anyone at any time, even for narcissists (which I am not even though I study them),” he began one missive, continuing, in characteristically run-on fashion, “but I will attempt to describe myself and my life in as much detail and overarching frame so people looking in from the outside can know me as a person and not just an accused arsonist.”

Born in 1974, Maynard had a middle-class upbringing in a town outside Columbus, Ohio. He told me he grew up “in the midst of rampant, soulless abuse” and claimed he had been molested by two different people. “My high level of intelligence,” he wrote, “made me odd, but very successful in school, and I quickly developed a deep love of learning and school which acted as a reprieve from the stark, empty and nearly loveless environment of abuse I faced.” After he graduated from high school in 1992, he decided to go to college in faraway Alaska, “a natural wonderland where wildlife and freedom was everywhere.”

Maynard is one of those people for whom higher education is not just a life stage but a life in itself. He spent the next two decades cycling through schools and degree programs. At the University of Alaska–Fairbanks, he earned a master’s in political science and developed a love of theater, performing in a campus production of The Mikado. Hoping to pursue acting, he moved to the New York area, studying for his second master’s, in theater history, at Stony Brook University. He soon shifted his focus to sociology, applying his interest in drama to the study of the ways humans perform in everyday life.

He could be a classroom motormouth. “You’d think he was kind of nuts,” says Paul Bugyi, a friend and fellow doctoral student. “If you stop him and say, ‘Clarify that,’ his answer is usually kind of brilliant.” Maynard wrote his Ph.D. dissertation on the effect of neoliberal trade policies on global public health, but his true interests lay in wilder material. He was fascinated by the 20th-century clairvoyant Edgar Cayce, known as the “sleeping prophet,” and once spent a year in his archives, researching his visions of the lost continents of Atlantis and Lemuria. Maynard taught classes on the 1993 siege of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, which ended in a firestorm. He also studied Jim Jones, the cult leader who committed mass suicide with 900 of his followers in 1978, and wrote a series of articles that suggested Jones exhibited traits of narcissistic personality disorder.

When we spoke, Maynard rejected any psychological interpretation of his interest in social deviance. He did acknowledge, however, that he thinks differently from others. He claims he has never been in therapy, but he has diagnosed himself with a variety of conditions, including Asperger’s syndrome. “I am not really sure it is a disorder,” Maynard wrote me. “I believe non-Asperger’s people live in a world of dumbed down delusions and lies covered in formal conventions where they don’t speak their mind.” I wondered whether sociology might have offered him an analytical framework to understand how he ought to interact with others, something that can be a challenge for people on the autism spectrum. He scoffed at that, replying, “I am more adept at understanding humans and society and reading emotions than almost anyone on earth.”

Maynard’s career ambition was to become a professor with lifetime tenure, but his timing could hardly have been worse. Universities were giving out more doctorates than ever while hiring fewer of their holders for tenure-track positions. The annual competition for the small number of jobs was crushing. In 2013, Maynard managed to make the shortlist for a post at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He had a wobbly interview and gave what some faculty members recall as a memorably uncomfortable practice lecture. “He was extremely anxious,” says H. Lyn Miles, a senior professor in the social, cultural, and justice studies department. “His legs were shaking, his toes were tapping.” But he won over the department chair, got the job, and moved to Chattanooga that fall. (The chair declined interview requests.)

Maynard’s friends at Stony Brook were worried. Grad school had provided a support structure, but he was fragile, and the publish-or-perish pressures of the tenure track could break anyone. Academic departments are practically constructed to be unmanageable, and Maynard’s new workplace was in the midst of an internal conflict over its leadership and hiring. “The catchphrase a lot of my female colleagues and I used would be ‘white guy with guitar,’ ” says Miles. Maynard fit the part.

Maynard told me he hated living in a small-minded city in Tennessee. The one person he connected with was a student named Satara Stratton. She was sort of famous, in a morbid way. As a teenager, Stratton had gone to Hollywood to become an actress and appeared in a few low-budget horror movies. Then she vanished. After a few months, someone dropped her off at an emergency room, suffering from a heroin overdose. The police suspected she had been living with a registered sex offender in a creepy old industrial building on Santa Monica Boulevard. Stratton claimed he had held her captive, shot her up with drugs unwillingly, and groomed her for sex trafficking. (The man was never charged.) She ended up telling her story on the true-crime-documentary series Disappeared. At 24, she returned to Chattanooga to stay clean and began living with her mother, an adjunct anthropology professor.

Stratton was taking sociology and anthropology classes, and Maynard worked with her as a faculty adviser on a research project. He spent a lot of time at her mother’s house. Her professors soon noticed a change in her behavior. Miles recalls that she turned in a class assignment that was nothing but a woozy silent film of Stratton walking through a forest.

One day in November 2014, Maynard was escorted from his office by campus police. “He was just gone,” recalls a former colleague. Stratton had made a sexual-harassment complaint against him and had told other professors that he had provided her with drugs. Maynard angrily confronted one of the professors who had reported the allegations to university authorities. The school convened a panel to investigate. Maynard denied making threats, said he had never given Stratton drugs, and claimed their relationship was not sexual. “I haven’t told her this before, but I am not sexually attracted to women,” Maynard told the panel. “I am gay, and … maybe she misconstrued what I did and what I said, and I’m sorry.”

To me, Maynard described the relationship differently. “We dated, and probably we fit in a lot of ways,” he said. He claimed he was the victim of “false accusations” made by others, not Stratton. “People got in the way,” he said. “They were jealous of our relationship.” He acknowledged going through a “briefly terrible cocaine addiction” after his mother’s death in the mid-1990s but denied using drugs during the period he was with Stratton. He claims he was “trying to help” Stratton overcome her own drug addiction. But Stratton’s mother, Sharon, blames him for her daughter’s relapse. “She was doing really well,” she says, “and then Maynard hit.”

Soon after Stratton made her complaint to the university, she and Maynard reconciled and moved to Columbus. For years, her mother saved an unhinged-sounding voice-mail she says Maynard left her, warning her not to come after them. “When he got in trouble with the university,” Sharon Stratton says, “he went off the deep end.”

Maynard launched a Kickstarter campaign to finance the publication of a book he claimed to be writing with Stratton. A cached record of the page says the working title was Heroin Princess: My Life As a Sex Slave and Heroin Addict. On May 7, 2015, local Ohio police arrested Maynard after five witnesses reported he had choked Stratton on the street in the middle of the day. Maynard says he was “arguing very vociferously” with Stratton about her continuing drug use but claims he never touched her violently. He ended up pleading down to a misdemeanor and was given a sentence of 60 days in jail, most of which was suspended. Stratton moved back to Chattanooga. In 2017, she died while visiting a friend in Los Angeles, most likely of a heroin overdose.

You can see all his handiwork,” Kate said as she showed me Maynard’s room. There were dimples in the floor and gashes in the walls. “Hammer,” she said, pointing to one spot of “Gary damage,” then another. “Hammer.”

Kate has a freckled face and untamed hair dyed a flaming red. “When he started having those violent outbursts, I realized he was ill,” she said, sitting on the patio in her backyard, near the garden Buddha. “But I was trying to help him, and I was trying to understand because I realized that this is a person that has been kicked down in life wherever he has gone.”

Maynard never told Kate about his meltdown at Chattanooga, but he did describe his difficulties in trying to make a living in academia afterward. He said he had been so broke that he was homeless at times, sleeping in offices, in his car, and even outdoors and going to university gyms to shower. “I used to tell him, ‘Gary, listen, this is not normal,’ ” Kate said. “ ‘You have a Ph.D. and three master’s. You should not be in this situation.’ ”

For an outsider, it’s hard to say what’s more shocking: a professor living in poverty or someone with Maynard’s record continuing to teach at all. But universities are happy to exploit the oversupply of academics desperate for work, hiring adjuncts on an annual or semester basis. Such jobs pay a pittance, and often the institutions do little vetting. “You’re not going to do deep dives on adjuncts that you’re paying $5,000 to teach a class,” says Diogo Pinheiro, a sociologist at the University of North Georgia who studies the academic labor market. While Maynard’s story of homelessness is extreme, a 2015 study found that one-quarter of people working primarily as adjuncts were on the SNAP food program or some other form of public assistance.

In the years after he lost his tenure-track job, Maynard bounced from Holy Family University in Philadelphia to the University of Michigan–Flint to Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He looked like a good job candidate on paper. His 2015 departure from Chattanooga, officially described as a resignation, had been disposed of without any publicity. Despite the debacle, he still received strong references from a few professors who had served as his mentors at Stony Brook. (They all declined interview requests.) Maynard’s varied interests made him versatile, and he could teach in related fields, including criminal justice, which tends to have high student demand.

In 2019, Maynard was offered the one-year job at Santa Clara. It appears that the administration was largely unaware of his personal distress, but a student in one of Maynard’s classes in the fall of 2019 says she could tell something was amiss. His lectures discussed his childhood trauma and took conspiratorial detours, going on at length about Jeffrey Epstein. None of her classmates wanted to complain — Maynard was an easy grader — but she was alarmed enough to save a copy of the evaluation she submitted after finishing the course:

This is the most ridiculous class I’ve taken at Santa Clara — an extreme outlier and an embarrassment to this institution. I’m usually skeptical when I hear my friends talk about how their professors ‘don’t teach’ or are ‘crazy.’ But this was truly the case with this class. The instructor’s lectures covered content only tangentially relevant to the course (they were mostly odd rants about celebrities and tech company founders), and multiple times per quarter, I questioned his well-being. He appeared to be vaguely psychotic.

If the life of an adjunct might drive anyone crazy, a university job might also offer a unique kind of shelter for someone in the midst of a breakdown. “It’s super-common to hear of undiagnosed mental illness in academia,” says Pinheiro. And given the independent nature of the work, he adds, “it’s super-easy for it to go unnoticed.”

Santa Clara gave Maynard another course to teach online in the fall of 2020, but his mental state was deteriorating. In October, someone called 911 in San Jose to report that Maynard had threatened suicide. A few months later, Maynard was kicked out of a co-working space in Oregon after the owner discovered he was spending the night there. Surveillance footage allegedly shows him roaming the room, raving and brandishing a knife.

He continued to find work. The following spring, Maynard taught at Chapman University, a school near Los Angeles, and Monterey Peninsula College. Anthony Villarreal, the sociology-department chair at Monterey Peninsula, told me that he needed someone to teach an online course on crime and deviance and that Maynard came highly recommended. They never met in person; the job interview took place over Zoom. “He was personable, he was clearly very highly literate, and he demonstrated a lot of intellectual curiosity,” Villarreal says. “His students seemed to enjoy the class. In the present, he was a better-than-average online instructor.”

In California, contingent faculty members are known as “freeway fliers” because they move around like nomads, often working at several schools simultaneously to make ends meet. Maynard said he enjoyed this contingent existence. “I was poor, but happy,” he wrote last October. “I was living in and out of my car, but free. I was innocent of any crime and still am.” But he remained angry that Kate had kicked him out. He sued her in small-claims court, alleging she had harassed him into self-evicting; the suit was dismissed in November 2020. The following June, when the SUV Kate had given him broke down, Maynard demanded a replacement. “If there is no car by Friday I will start some serious trouble for everyone that has stood by and just watched as I have died inside over the past few weeks,” he texted Kate. “I hate this world and if I have to go more than one or two days without a car then I will end the whole world from the disease of humanity.” (He told me he had meant this as a dark joke.)

Kate had some financial security. Her house was worth a lot, she figured, and her sister had gifted her some bitcoin. She gave Maynard several thousand dollars. In late June, he texted Kate a short video capturing the view through the windshield of his new Kia hatchback as he pulled to the side of a road in a verdant Northern California forest.

“Finally with the trees,” he said. “Ahhhhhh … They missed me so much, and I missed them.”

If there was one thing that Maynard wanted me to know, it was that he loved trees and would never hurt them. On his YouTube channel, there is a video from 2020, made for one his classes, in which he walked among the redwoods. “If we are supposed to be highly intelligent,” he ruminated, “how are we taking care of these creatures?”

“It’s absurd for people to accuse me of trying to destroy a tree,” Maynard told me. He said he believes trees are conscious beings. “Maybe that’s ethereal or woo-woo.”

What could possess someone to commit an act as nihilistic as setting the natural world ablaze? Criminologists have no simple answer, even as the act becomes more prevalent and destructive. Wildfires are usually not wild in nature. Nine times in ten, they originate from human activity. Often, the cause is purely accidental, but an estimated 10 to 20 percent of human-caused wildfires are attributable to arson; many investigators believe that’s an undercount. The crime is inherently solitary, and fires often obliterate the evidence of their ignition.

California’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, known as Cal Fire, reports that its agents have arrested more than 350 people for arson since 2020, a marked increase over prior periods. There is no consensus as to why the numbers are climbing. Maybe they’re correlated to the overall increase in wildfires. Maybe it’s a consequence of development’s encroachment into areas prone to combustion. Maybe it’s because more people are living in tents. Maybe it’s because we’re all getting angrier. “A lot of fire people, like myself, see the whole haze of social unrest and economic dysfunction playing a role here,” says Glenn Corbett, an associate professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

What is indisputable is climate change has increased the risk that any given fire will grow to apocalyptic proportions. An arsonist has no control over a blaze once it gets burning. Environmental conditions determine how far it spreads. If fire has enough fuel and wind, it can have the power of a weapon of mass destruction. Drought conditions and an abundance of dry tinder have created ideal conditions for “megafires,” as wildfires covering more than 100,000 acres are called. Once rare, they now break out on a regular basis, engulfing whole towns, causing billions in damage, and killing firefighters and civilians. As the threat has grown, law-enforcement agencies have only just begun to devote more attention to wildland arson. “No one really cared too much about it,” says Ed Nordskog, a former Los Angeles sheriff’s-department detective and arson investigator, “until these catastrophic fires that keep coming and coming and coming.”

An arsonist who burns down a house to collect insurance or exact revenge is acting on a recognizable criminal impulse. One who sets fire to nature is a stranger animal. Nordskog believes that commonly accepted ideas about the crime, and the kind of people who commit it, are largely based on “ancient, incredibly poorly constructed studies.” Just a fraction of wildland cases are ever solved, and even the most prolific perpetrators, the serial arsonists, tend to get caught only when they make stupid mistakes. Nordskog likes to sarcastically rattle off the attributes listed in the FBI’s generic profile of a serial arsonist — lone white male, 18 to 34, poorly educated, angry and disenfranchised, fascinated with police and the military, sexually dysfunctional, a heavy drinker — and joke that it describes everyone he has ever worked with in law enforcement.

“Race is not a factor, and age isn’t, other than they have to be old enough to drive a car,” Nordskog says. Women, he adds, account for around 20 percent of wildland-arson cases. In 2016, he self-published a handbook, The Arsonist Profiles, which categorizes fire setters by their methods and motives and debunks a number of myths. He derides one of the most popular psychological constructs, pyromania, as “salacious” Freudian nonsense. Although mental illness clearly plays a role in most cases, true pyromaniacs, who compulsively create fire for pleasure, are extremely uncommon.

Wildland arsonists show more control and wait for the right moment. Many act from specialized knowledge. Studies have found that around 35 percent of wildland arsonists have a connection to the fire service. If investigators do notice a common theme in the confessions of wildland arsonists, it is a sense of failure, often exacerbated by mental illness. “They’re mostly very broken people,” says Paul Steensland, a retired U.S. Forest Service investigator. “They have very deep feelings of inadequacy from an emotional standpoint, and the fire gives them the power.”

The average serial arsonist is charged with starting three fires but is suspected of setting ten times as many. Perpetrators often remain at large for years. In 2006, a fire set near Palm Springs caught the Santa Ana winds and turned into an inferno that killed five firefighters. The arsonist, a mechanic named Raymond Oyler, was convicted of murder and is now on death row in California. In 2016, an ex-con named Damin Pashilk was arrested for setting a blaze that ravaged Lake County, California. He is serving a 15-year prison sentence. Both men turned out to be serial arsonists who had been setting small fires for months before the big ones that led to their arrests.

One day in July 2021, a rotted tree fell on a power line in a mountainous area of Butte County, California, and ignited dry brush on the ground. The Dixie Fire, as it was named, quickly moved across the parched terrain. On July 19, it exploded. The intensity of the flames caused an updraft effect, pulling superheated air into the upper atmosphere and creating what scientists refer to as a pyrocumulonimbus cloud — a 40,000-foot thunderhead of smoke and ash — under which a storm of wind and lightning raged.

The next morning, Maynard drove up a winding two-lane highway that climbs the western slope of Mount Shasta. “The flames were so huge that they were coloring the sky,” he recalled, giving it “a pinkish-red hue.” He turned onto a rough dirt road.

A 33-page criminal complaint, prepared by a special agent with the U.S. Forest Service, picks up the story at around 9:45 a.m. (Maynard and his attorney have not yet had an opportunity to challenge the government’s version of events in court.) A mountain biker smelled smoke as he rode a rocky path through the towering firs of the Shasta-Trinity National Forest. Roughly 75 yards from the trail, he found a small brushfire. He and another biker dug a trench around its perimeter and stomped the flames at its edge, keeping it in check until firefighters arrived. Their quick action confined the burn to an area under 200 square feet.

A Forest Service investigator arrived and found two cars nearby. One was stuck in a rut, wedged onto a large boulder. It was Maynard’s Kia. He was underneath, working to get it free, and appeared agitated and incoherent. He murmured something about being a professor. The investigator noted Maynard’s name and license plate and moved on.

A little before 3 a.m. on July 21, a second blaze was spotted and extinguished along the same Mount Shasta highway. The investigator and a colleague returned to the scene of the first fire. Maynard and his Kia were gone, but the owner of the second car was still present. He told the investigators that Maynard had been acting strangely and waving a knife. Near the boulder where the Kia had been stuck, the investigators allegedly found a small pile of charred sticks and fluffy pieces of burned newspaper.

“I’d have to be the dumbest criminal on earth — and I am not a criminal, and I am not dumb — to start a fire where my car is stuck,” Maynard told me. When I pressed him to say exactly what he was doing in the forest, he offered a shifting series of explanations. He mentioned a legend involving people from the lost continent of Lemuria who supposedly live inside Mount Shasta. After prosecutors disclosed they had retrieved video footage from his phone, he elaborated, telling me he was making a “mockumentary” film called Postmodern Patriot, in which he played a veteran sucked into a vortex of Trumpian conspiracy theories.

In texts he sent to Kate at the time, he expressed paranoid delusions. He believed he was being followed by Mormons and claimed he was an heir to Joseph Smith. “The stalking is real and criminal and they are running me all over,” Maynard wrote to her. “I have no peace from them and you cannot just tell me that I am crazy.”

The stalkers may have been imaginary, but Maynard was really placed under surveillance shortly after his encounter with the Forest Service. On August 3, 2021, two weeks after the first fire, he was tracked to a grocery store in Susanville, a dismal former logging town on the edge of Lassen National Forest. Local police pulled him over for a traffic violation. While Maynard was distracted, a Forest Service agent sneaked up and stuck an electronic beacon under his car.

According to the federal criminal complaint, Maynard left Susanville on Highway 36, heading in the direction of the nearby Dixie Fire, which was continuing to grow in ferocity. He turned this way and that, driving down logging roads and continuing deep into an area of scrubby pines and tall Douglas firs. When he stopped, the rust-colored volcanic soil was so dry, Maynard recalled, that whenever he took a step, it puffed up like moondust. Eventually, he found a remote place in the forest to camp for the night.

Maynard claimed he was merely looking for a secluded spot to shoot footage for his movie. On the afternoon of August 5, he drove away from his campsite, winding his way back into the woods he had explored a couple of days earlier. The area was now under an evacuation order. A Forest Service officer tailed Maynard as he turned onto a paved road. Along a straightaway, the officer spotted a newly lit fire. According to tracking data cited in the criminal complaint, Maynard had driven past the spot and parked down the road for a minute and eight seconds, as if he’d stopped to watch something, the document hypothesizes.

Maynard spent the next day at a second campsite, less than a mile from the site of a 2020 wildfire that had burned nearly 10,000 acres, leaving behind a blackened landscape. The trunks of dead pines stood out like long whiskers. “Gary, get out of the forest,” Kate texted. “It’s very dangerous.” She had been at him for days, urging him to find a psychiatrist. He dismissed her concerns, telling her at one point that God had called for him to walk “on unstable and uneven ground.” On August 6, he sent her a video clip of a local news report that the Dixie Fire had overtaken the historic town of Greenville, burning its Old West main street to the ground in 30 minutes. Maynard’s phone kept buzzing with warnings of danger. The air around the campsite was thick with reddish-black smoke. Embers were wafting to him through the air.

The next morning, Maynard left his campsite the way he had come, bumping over tracks through the forest. “Are you safe?” Kate wrote. “I am with the trees and as they go I will go,” Maynard replied. “It is wrong and existentially wrong that they burn and die because of people.”

The government alleges that, after Maynard departed, the agents monitoring him went to check out his campsite and ran into a pillar of smoke. At least a half-acre of the forest floor was burning. Maynard’s car proceeded to a spot six minutes away, according to tracking data, where a second fire was discovered. A few hours later, a California Highway Patrol officer arrested Maynard as he drove back toward the alleged scene of the crime. The car was impounded, along with the phone mounted on its dashboard.

None of the fires Maynard is alleged to have set spread very far, though that may simply be because he was under surveillance with firefighters following right behind him. Nordskog, the arson investigator, says size distinctions matter little: “Every fire in the wildland is potentially a catastrophic event. They all start out the size of a match.”

After Maynard’s arrest on August 7, he was taken to a police station in Susanville. Prosecutors allege he was violent, kicking his cell door and shouting at a sheriff’s deputy, “I’m going to kill you, fucking pig!” (Maynard told me the verb he used was sue.) Investigators suspected they had interrupted a diabolical plan. Prosecutors produced a map of three of Maynard’s alleged fires in relation to the crescent-shaped footprint of the Dixie blaze, suggesting his goal was to create an encirclement. In court, a prosecutor argued against granting Maynard bail, describing him as a “very knowledgeable” arsonist whose string of fires “could not have been better plotted in order to trap firefighters.”

Several experts told me this scenario was far-fetched — it would have required an aerial view and knowledge of firefighters’ locations. A federal judge was inclined to release him, but Maynard was initially unable to put up the $25,000 bond, so in the meantime, he remained in jail as he awaited trial. An indictment handed down in November 2021 included four counts of arson to federal property, each of which carries a potential sentence of five to 20 years.

In December, Maynard was transferred from Sacramento to a county jail in Nevada City, a charming town in the foothills of the Sierras. “I haven’t had a chance to walk around,” he said, “but I can look out the window and see the trees.” He described the prison’s sociology — its gangs and ethnic cliques, its hierarchies, its petty injustices and methods of control. He told me he was looking forward to resuming his academic career once he was exonerated. He also told me he regularly talked to spirits of the dead, including Satara Stratton. “She and another friend that I have are in my room,” he said. “They have served eight months with me too.” The next day, he called back to say the other spirit had given him permission to disclose his name. It was River Phoenix.

At one point last year, Maynard was hoping to be released on bail; Kate had agreed to pledge the money. But then prosecutors, with assistance from the FBI, were able to crack into his locked iPhone, which contained a litany of evidence. In a government filing, several videos shot by Maynard are described in damning detail. One allegedly shows him threatening the home of a person who had erected a gate that prevented him from driving across private land. “I’ll just burn this to the ground,” he allegedly says. “That’s what you win. You win a wildfire right in your house.” Then the video allegedly captures the sound of Maynard rolling down a window and striking a match.

A second video allegedly shows him chasing down a mother and three children he had seen at a gas station. “What’s wrong, kids? What’s wrong?” he whispers as he drives. “Maybe you should stop pissing people off and they won’t fucking follow you to their house.” When the frightened mother pulls into a police-station parking lot, Maynard allegedly screams, “I will kill your fucking family right in front of you, bitch.”

A few days before Christmas, a judge denied Maynard’s motion for bail. “It’s called guerrilla theater,” Maynard told me after the hearing, sounding rattled. “Juries aren’t stupid. They’re going to see the distance between a character and reality.”

In early March, I went to see Maynard in Nevada City. (The jail did not permit me to take in a notebook, so I transcribed the meeting from memory immediately afterward.) He entered the visiting room, a spare white cinder-block corridor lined with booths partitioned by thick glass, and picked up a phone. “I’m okay,” he said. “As okay as I can be, being unjustly accused.” He wore an orange jumpsuit, a white cloth mask, and half-framed glasses. He looked emaciated, and his sandy hair had gone long and feral in the back.

“I am not an arsonist,” Maynard said adamantly. “Why would I risk my career like that? Why would I risk my freedom?” He brought up the cell-phone footage. He told me it would be evident to all, once his film, Postmodern Patriot, was viewed in its entirety, that he was simply playing a deranged character. He told me he had continued to shoot footage right up to the day he was arrested. He mentioned a scene where he stood among burning trees. He went so far as to claim that the videos the prosecutor in his case found so incriminating are actually evidence of his brilliance as a dramatist. “He called it ‘chilling,’ ” Maynard said. “I was so flattered.”

Madness, he seemed to be saying, was just one more mask he wore. He said he felt like the prosecution was trying to “make me look like an erratic idiot” to bully him into a guilty plea. “My reverence for trees, I think, hopefully will come out in the trial,” Maynard later told me on the phone. Over and over, he repeated his belief that once he had a chance to make himself understood, he would be free to return to the forest. “I wish the trees were on the jury,” Maynard said. “Because they would acquit me.”