This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On September 4, 2018, Nauman Hussain, a 28-year-old professional paintball player, was working at his family’s business when a state inspector arrived for a routine visit. Nauman’s father owned Prestige Limousine, a small company touting “modern, classy vehicles” for “exquisite wedding, prom, event, and special occasion” transportation in the Albany area, and Nauman operated it day to day, sometimes answering to his father’s name. The inspector examined Prestige’s vehicles and placed an orange-and-white sticker roughly the size of a license plate on the windshield of its workhorse, a Ford Excursion. “OUT-OF-SERVICE,” it read. “This motor vehicle has been declared UNSERVICEABLE.”

The Excursion was a beast, a 10,000-pound SUV that had been chopped in half and welded back together with 12 extra feet of carriage in the middle, effectively turning it into a bus. It was a party vehicle, or a party gag, the kind of limo that made you wince and check the leather seats for stains. State inspectors knew Prestige’s Excursion well. They regarded it as an insult to their profession and “violated” it whenever they could.

The Hussains always managed to get it back on the road. Six months earlier, the limo had failed inspection for a long list of deficiencies, including corroded and compromised brakes. Someone had crudely disabled one of the lines with a vise grip. The Excursion’s regular driver, a 53-year-old named Scott Lisinicchia, knew the vehicle had problems and preferred to operate Prestige’s other limousines. But on Saturday, October 6, a little after 9 a.m., Lisinicchia got a call. Nauman Hussain wanted him to take the Excursion out on a job. The windshield sticker was gone.

At 1 p.m., Lisinicchia pulled the limo up to a home in the town of Amsterdam. Axel Steenburg, a 29-year-old bodybuilder who worked at a semiconductor plant, was organizing a 30th-birthday celebration for his wife, Amy, and a big crew. Seventeen of them, including Amy’s three sisters, Axel’s brother, and several other young couples, were going day-drinking at Brewery Ommegang in Cooperstown, some 50 miles away. The Steenburgs had figured that hiring a sober driver seemed like the safe thing to do.

As the celebrants piled into the Excursion, they found sickly neon-colored lights, padded benches, and floorboards that had rusted through. One of the partygoers texted a friend who had planned to attend but backed out.

the limo sounds like it’s going to explode

yes haha it’s a junker literally

the motor is making everyone deaf 😭😭😭😭

Lisinicchia took an odd path to the brewery. Avoiding a direct route along the highway, he embarked on a meandering course along small rural roads. It might have seemed like an easier drive for the lumbering Excursion, now carrying some 3,500 pounds of people, but the route’s steep hills and frequent stops had the opposite effect, further stressing what remained of the brakes. In back, the passengers could smell something burning.

By 1:45 p.m., the Excursion was south of Amsterdam in the rolling Schoharie Valley, an hour from the brewery and heading in the opposite direction. Lisinicchia drove hesitantly, as if he were trying to figure something out. On Route 30, at the top of a hill, he shifted to the breakdown lane.

A Jeep came up from behind. Its driver, Holly Wood, a worker for the county government, noticed the limo had its back-up lights on yet was inching forward. “That’s weird,” she said to her daughter, who was sitting shotgun. Wood turned down the radio, lowered the window, and heard the bleat of the limo’s back-up alert. Through tinted windows, she could see the passengers’ silhouettes. Lisinicchia was pointing toward something in the distance. Wood passed the limo and drove on.

Behind her, the Excursion kept rolling and began to pick up speed, accelerating down a winding road that plunged almost 600 feet in less than two miles. There was nowhere to pull off. Lisinicchia was pumping the useless brake pedal so hard it deformed in the shape of his loafer.

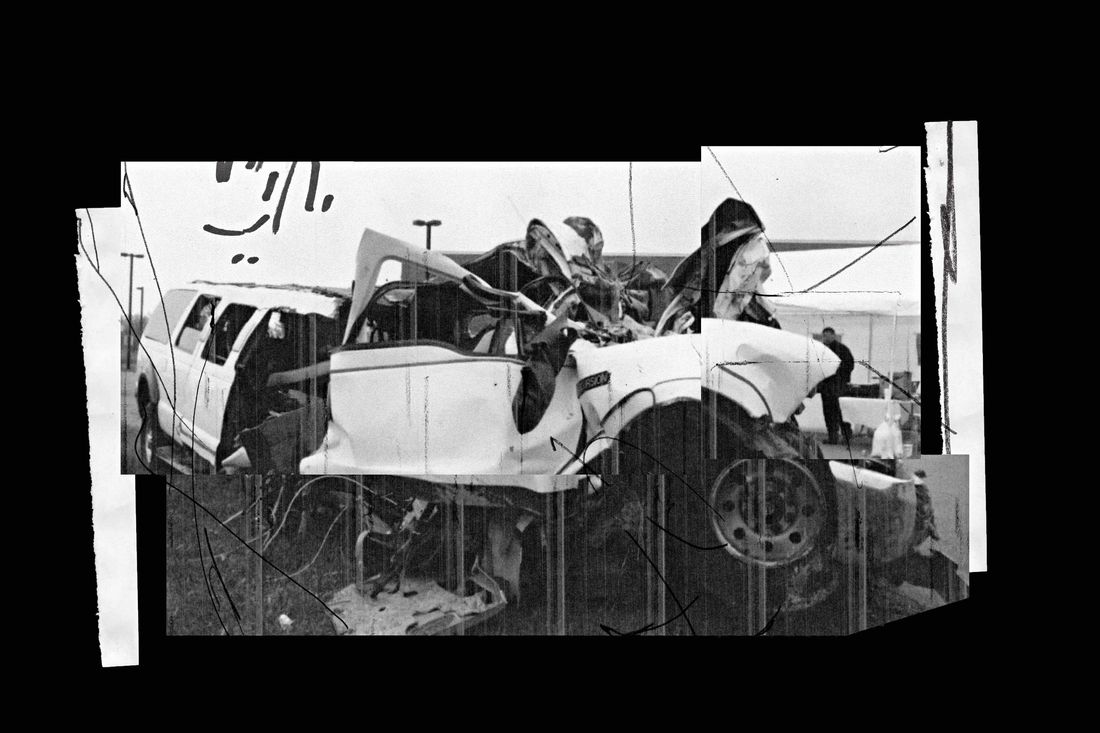

At the bottom of the hill, Route 30 terminates in a T-shaped intersection with another state highway. Wood and her daughter sat there waiting to turn. She looked in her rearview mirror and saw the 31-foot Excursion hurtling directly toward them at as much as 118 miles per hour. The sound in her ears was like a jet engine. Wood had enough time to tell her daughter to hold on and then there was a white streak as Lisinicchia swerved past and across the busy junction.

On the far side of the road, in the parking lot of a country store, the Excursion smashed into a stationary Toyota Highlander, launching the 4,000-pound SUV 80 feet. Standing nearby, two members of a family en route to a wedding were crushed. Even after destroying the Highlander, the Excursion was traveling at 80 miles per hour. It ended up in a ditch, impaled upon itself, the engine bay all but flattened. From the outside, the passenger compartment looked uncannily intact. Inside, blunt-force trauma had instantly killed 16 people. Two more died within hours. None of the passengers had been wearing seat belts, and their bodies broke against the walls, the ceiling, and one another. The carnage was so extreme that veteran paramedics attending the crash site developed disabling mental-health issues.

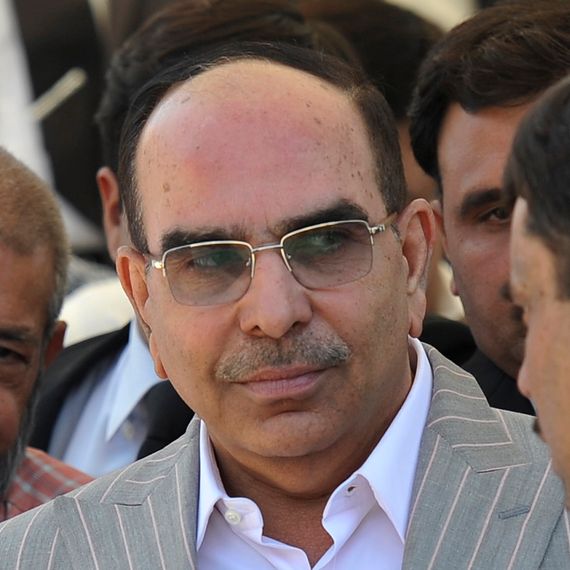

Nauman Hussain was informed about the crash by a call from a New York State trooper. “Is this a prank?” he asked. Four days later, he was arrested at a traffic stop outside Albany and charged with criminally negligent homicide. News photographs from his arraignment show a muscular young man in a black V-neck shadowed by his glowering older brother, Haris. Among the items seized from Nauman’s Infiniti QX56 were a passport application and a shredded piece of paper — the OUT-OF-SERVICE sticker that had been glued to the windshield of the Excursion.

Nauman posted bail, went home, and refunded $1,475 to Axel Steenburg’s credit card. A few weeks later, he traveled to Kissimmee, Florida, for the 2018 Paintball World Cup at Gaylord Palms Resort & Convention Center, where his team, the New York Xtreme, registered a disappointing 14th place.

The Schoharie tragedy was the deadliest transportation disaster in the U.S. in almost a decade, including plane crashes. It was one of the worst single-car wrecks in the history of the automobile, comparable only to accidents involving buses or trucks that caught fire, sank, or fell off cliffs. But the story would likely have faded from awareness, as car crashes invariably do, if not for one factor: Nauman Hussain’s father, Shahed, the owner of Prestige Limousine, was a longtime confidential informant for the FBI and one of the most notorious operatives in the agency’s history. In upstate New York, where a pair of federal terrorism investigations had left Muslim communities seething and in despair, many people gasped when they saw his name connected with the Schoharie crash.

“It’s this feeling that we’re cursed,” says Steve Downs, an Albany lawyer and political activist. “Each time his name comes up, you say, ‘This is it. We finally got to the end.’ But it just keeps coming back — this guy.”

The impact of Hussain’s FBI cases was not confined to the region. They were legal landmarks in the War on Terror, helping establish the legitimacy of secret evidence, warrantless wiretapping, and the government’s practice of inventing terror plots to entrap ordinary Americans with no prior connection to violent Islamic groups. For this, the Hussain family received hundreds of thousands of dollars, which helped them open and operate several businesses around Albany. Prestige and the others racked up safety violations, some of them egregious, yet were never shut down by regulators.

“The FBI enabled Shahed Hussain to feel that he could get away with anything,” says Kathy Manley, an Albany attorney who has represented men still serving multi-decade prison terms because of Hussain’s undercover activities and who sees a connection between his anti-terror work and the 20 dead in Schoharie. “He clearly didn’t care about the limousine being unsafe, and apparently neither did his son.” The larger unanswered question is whether anyone in government had helped the Hussains when their businesses ran into trouble over the years. If they had, it would make the government complicit in an unspeakable catastrophe. Few in power are willing to discuss Shahed and Nauman Hussain. One of the sources who did, when I began to call around last winter, speculated that the family belongs to a class beyond the reach of law enforcement — whose leverage confers something close to impunity.

If his story is to be believed, Shahed Hussain arrived in Albany in 1994 as a political refugee. With his wife, Yasmeen, and two boys, Nauman and Haris, Shahed claimed to have fled sectarian conflict in Pakistan, with a scar he said was proof — a mark on his wrist from being tortured in custody. There were rumors in Albany’s Muslim community, however, that Hussain had come to the U.S. to escape not oppression but a criminal investigation involving a murder.

In the Capital Region, the Hussains seemed to make a seamless transition to upper-middle-class life, settling into mansion-lined Loudonville, where Nauman and Haris attended one of the area’s top elementary schools. Shahed, a nonstop talker with dark hair and an alligator grin, came to own or operate several businesses, including a gas station and a venture to import small consumer goods. A few months after the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, he was arrested as part of an identity-fraud ring. According to court documents, the scam originated when Hussain had his driver’s license taken away for failing to maintain one of his cars. After paying a mechanic to falsify repairs, he persuaded a DMV clerk to clean up his record. Soon, he was plying the clerk with cigarettes for illegal IDs, mostly for other Urdu-speaking immigrants.

The charges he faced were serious, with national-security implications: Several of the 9/11 hijackers had used illegal licenses. Hussain was in danger of being deported. But the FBI was desperate to discover potential terrorists in the United States, and the agency offered him a deal to become a confidential informant.

In his new role, Hussain, who claimed to speak five languages, was enthusiastic and effective. His FBI handler later testified that he was “good at being deceptive,” adding, “like an actor — so he was presenting a role, and he was very good at that.” His first targets were members of his own identity-fraud scheme, including a girlfriend he testified against; another case involved infiltrating an Afghan heroin ring. Hussain’s personal life, though, was turning chaotic. He filed for bankruptcy in the summer of 2003, and that October, a fire destroyed most of the family’s home. The blaze nearly killed Yasmeen, who was forced to jump out a window. FBI agents showed up at the scene, where their informant was refusing to talk to investigators from the fire department.

Hussain was about to take on his most significant assignment yet. Based on evidence recovered in Iraq, the government suspected the imam of an Albany mosque, a Kurdish refugee named Yassin Aref, was a terrorist commander. The FBI asked Hussain to wear a wire and engage Aref on the subject of violence against America. Posing as “Malik,” a wealthy importer of Chinese goods, Hussain began attending meetings at the mosque. The congregation included a Bangladeshi pizzeria owner who was in financial trouble, and Hussain offered him a $50,000 loan. He also showed the man a surface-to-air missile. “But it’s not legal,” the pizzeria owner said. “What is legal in this world?” Hussain replied.

When it came time to transact the loan, the men agreed that a fellow Muslim should serve as witness. Aref said yes to the task. At a fake office in a dreary shopping plaza near Albany International Airport, with the FBI watching through a camera hidden inside a clock, Hussain tried unsuccessfully to get Aref to praise Osama bin Laden and condone suicide bombing. He also made oblique references to a plot involving a missile, but Aref, whose English was limited and who had never seen Hussain’s supposed anti-aircraft weapon, ignored the remarks.

As far as getting the men to participate in or endorse violence, the sting was a bust. But that didn’t matter. Neither Aref nor the pizzeria owner ever reported Hussain or his jihadi bombast to law enforcement. The government deemed that this was itself an indication of wrongdoing. The men had “failed” a “test,” as a prosecutor put it, and in 2004 the Justice Department charged them with a range of crimes, including money laundering in support of terrorism.

Steve Downs, the Albany lawyer, read about Aref and came out of retirement to join his defense. Downs had spent his career with the New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct, investigating corrupt judges and prosecutors. Their crookedness struck him as prosaic. “People were lazy, they were sloppy, they didn’t care,” he says. “There was nothing particularly shocking about it.” Aref’s prosecution, however, struck him as desperate, vicious, and un-American. He regarded it as a criminal act and one of the worst betrayals of public trust he had ever known. “This was the first case I’d seen where the government prosecuted a man they knew was innocent,” he says.

Aref’s case outraged civil libertarians, not only for its reliance on entrapment but for its use of secret evidence. Prosecutors presented material that Aref’s lawyers were forbidden to see, let alone challenge. (The New York Times reported that the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping program played a role in Aref’s arrest.) Even with such advantages, the case almost collapsed. Prosecutors acknowledged that a crucial piece of evidence had been mistranslated and that it referred to Aref not as commander but merely brother. A federal judge reversed himself and granted the defendants bail. “After one year’s undercover operation and surveillance, the government and the FBI have come up with no real evidence that the men are connected with terrorist groups,” he said.

Hussain rescued the government at trial, where he was the prosecution’s star witness. According to Kevin Luibrand, another defense lawyer, the turning point came when Hussain, who arrived in court escorted by FBI agents, testified that the defendants had shrugged when he told them about an impending attack on New York City. There was no tape of the alleged conversation — Hussain claimed he had dropped the recorder — but the jury was shocked. Aref and the pizzeria owner were convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

The FBI paid to relocate the Hussains to Memphis, Tennessee. They were no longer welcome in Albany, where the Muslim community regarded Shahed Hussain as “the lowest of God’s creations on earth,” according to Shamshad Ahmad, a co-founder of the mosque where Aref had preached. With $60,000 in compensation for his undercover work, Hussain resolved his identity-fraud charges with a guilty plea and a fine of $100.

As in Russell Banks’s 1991 novel The Sweet Hereafter, about a fatal school-bus accident in an upstate hamlet, the limo crash seemed like a targeted demolition of a community — a cataclysm that “wiped out nearly whole generations of some families,” according to the Albany Times Union. Afterward, the victims’ survivors were tortured by unanswerable questions: Why didn’t the driver pull over sooner? When did the passengers realize what was happening? Would such a death trap have been on the road if its owner hadn’t been a precious government asset?

Shahed Hussain’s symbiosis with the FBI has been richly documented. There have been books, most notably The Terror Factory, by Trevor Aaronson, as well as newspaper investigations, magazine articles, and documentaries — plural. But as a rule, people in power here will simply not discuss whether Hussain’s undercover work played any role in allowing his businesses to flout safety regulations. Take, for example, Democratic congressman Paul Tonko, a “son of Amsterdam” who knew many of the victims. Last year, Tonko’s then–communications director, Matt Sonneborn, began an hour-long interview by specifying that neither he nor Tonko would have anything to say about the Hussains or the FBI. Chris Tague, a genial Republican assemblyman from Schoharie, burst into tears when I called. Like many in Schoharie, Tague has been traumatized by the crash, but between sobs, he made it clear: The Hussains and the FBI were a no-go area.

This reticence is not prevalent outside Albany officialdom. On the contrary, the first thing one learns about the Hussains is how obsessed people are with them: lawyers, journalists, activists, members of the upstate Muslim community. That makes sense, of course — the innermost circle of hell is for traitors and snitches. But Shahed Hussain does not appear to have been a typical snitch.

The Hussains did not last long in Memphis before returning to Albany in 2006. That July, the burned shell of the family’s former home was purchased for $450,000, more than three times its former value. (The transaction is one of many events in Hussain’s life that have never been fully explained. Property records show a buyer with a Tennessee address that Hussain has also used to conduct business. Investigators for the mortgage company have never been able to locate the person, and the local newspaper reported that he “appeared not to exist.”) Hussain used the windfall to purchase the Hideaway Motel, an establishment near the Saratoga Springs racetrack. He renamed the property the Crest Inn and shifted the business model, renting squalid bungalows to low-income residents whose stays might be paid for by the state. (Unsuspecting travelers would sometimes drift in and leave withering reviews on Tripadvisor. “I’ve slept in mud and felt less disgusting,” read one.)

Hussain also went back to work for the FBI — this time with a new level of responsibility and independence. Previously, the agency had selected his marks; now it was his job to identify people who could be talked into phony terror schemes. In 2008, he found a target-rich environment in Newburgh, an enduringly poor city in the Hudson Valley that was home to a large mosque, Masjid al-Ikhlas. Every Friday for more than a year, Hussain would drive 90 minutes downstate, park outside the mosque in a BMW or Hummer, and mingle after prayer with the congregants, some of whom were low-level drug offenders rebuilding their lives after prison.

One of these was David Williams, a soft-eyed 27-year-old who had recently served time for drug possession. His mother, Elizabeth McWilliams, remembers the day David introduced her to Hussain. “He said, ‘I want your son to work for me in clothing distribution,’ ” McWilliams says. Hussain, who was using the alias “Maqsood,” immediately made her nervous: “We drove past a car and he said, ‘Look at them Jews. We should kill them.’ I said, ‘How do you know they’re Jews?’ He said, ‘Don’t you see the little curls?’ I said to David — excuse my French — ‘What kinda motherfucker you got me in the car with?’ ” As she recalls the incident, McWilliams, who is now 60, wears a cutoff T-shirt revealing broad shoulders and cannonlike arms. She says she once told Hussain, “There’s something about you, and when I put my finger on it, I’m gonna let you know what it is.”

By the time she did, it was too late. Hussain had enmeshed her son and three other Black men in a scheme to blow up a military airplane and two synagogues. None had terrorist connections or weapon-making abilities. “These guys had absolutely no religious or political beliefs,” Kathy Manley, who represented some of the men, says. “They weren’t even really Muslim.” But the men had dim prospects. Williams was a part-time college student, another was a stocker at Walmart, and one was a homeless immigrant with severe mental illness. Hussain offered them a BMW, a vacation, and hundreds of thousands of dollars, and they followed along as he gave them what they thought were bombs and a Stinger missile.

On the night the FBI arrested Williams and his associates, agents raided his mother’s apartment, kicking down her front door. “They came out in helicopters, in gas masks,” she recalls. “I was on the toilet. I said, ‘You gonna let me wipe my ass?’ They was standing right there with a big dog. So I wiped my butt, and I showed him the toilet paper so he could see the shit on it. He turned around and then he took me in the room, and he opened up the curtains and the light from the helicopter was shining. I still didn’t know who they was and then I seen on his jacket, HOMELAND SECURITY. And that’s when I said, I’m in some big shit.” Evicted after the raid — the government refused to cover the damage to her apartment — McWilliams found herself homeless, bathing in McDonald’s bathrooms on the way to work.

Her son was charged with conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction and conspiracy to acquire and use anti-aircraft missiles. Just as in the Albany case, the judge castigated the prosecution. “I believe beyond a shadow of a doubt that there would have been no crime here, except the government instigated it, planned it, and brought it to fruition,” said Judge Colleen McMahon.

Hussain testified for 13 days. Written up in the national press, his testimony was the trial’s blockbuster centerpiece. He portrayed himself as a swashbuckling operative who had worked more than 20 cases for the FBI. Defense lawyers, eager to cast the government’s star witness as a fabulist, subjected him to a brutal cross-examination. They argued convincingly that Hussain had lied on his tax returns and immigration papers and had even misled his FBI handlers. Hussain seemed incapable of giving a straight answer. “Yes or no!” the judge shouted at him during one exchange. “I’m tired of your playing games.”

These aspersions faded after the jury reviewed the audio and video evidence Hussain had compiled, which showed the defendants scouting locations to fire shoulder-mounted missiles, spewing hatred about Jews, and discussing what their code names should be. The Newburgh Four, as they came to be known, were convicted in October 2010, setting a precedent that in terrorism cases, citizens have little chance of succeeding with an entrapment defense against the government.

David Williams has spent much of the past 12 years in the Pollock Federal Correctional Institution in Louisiana, often in solitary confinement. The prison is nearly 2,000 miles from his family, who haven’t visited since 2015. As Elizabeth McWilliams describes his ordeal, she begins to shake violently and has to leave the room. “I never was a person that thought about killing somebody,” she says quietly when she returns. “I have that in me now. I feel like I could kill somebody. That’s why I tell people I am not the person to mess with because, I swear to God, I could kill somebody. I never felt like that. Because I used to speak to my son every day. I could smell him. I could close my eyes, and that was my child.”

Why was Shahed Hussain doing this — adopting alter egos, concocting elaborate acts of destruction, ruining lives? It wasn’t the threat of prison. After the Albany case, the government had no more leverage on him. The next most plausible incentive was financial. “We were convinced that Mr. Hussain was a poor person who had extreme motive to lie for money,” says Mark Gombiner, a lawyer for one of the Newburgh Four.

But that wasn’t driving Hussain either. “In fact, he had huge amounts of money available to him,” says Gombiner. The lawyers discovered during the proceedings that Hussain had been receiving funds from Pakistan since the mid-1990s — almost $700,000 in total. Much of the money went through the Crest Inn. “There is money flowing in and out of this deadbeat motel up in Saratoga Springs,” says Gombiner. “We don’t know what it is. Maybe there is an innocent explanation, but it’s highly suggestive of some sort of criminal activity, money laundering, some attempt to disguise funds.”

At the trial, Hussain claimed that he came from a rich family and that the money had come from a trust fund and even in the form of a gift from Benazir Bhutto, the late prime minister of Pakistan. This was seen at the time as fabulizing. But it was not: Hussain indeed comes from a prominent Pakistani family, one with ties to the highest levels of the military and the intelligence service. His oldest brother, Malik Riaz Hussain, is a billionaire and, in his country, a household name synonymous with wealth and graft.

The 72-year-old Riaz (his third name is typically omitted) began his career as a modest clerk, then became a military contractor. As the army became the de facto ruler of the country, he leveraged an unparalleled facility for bribery into one of the largest real-estate portfolios in Asia. The alleged beneficiaries have included the son of the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan; in 2019, without admitting guilt, he agreed to a settlement with the U.K.’s National Crime Agency to hand over £190 million in assets (including a £50 million house overlooking London’s Hyde Park) that authorities said might have been obtained illegally. Britain has rescinded his visa, with a judge writing, “Your exclusion from the U.K. is conducive to the public good due to your conduct, character, and associations.” “He buys everything,” says Ayesha Siddiqa, a prominent Pakistani scholar. “Judges, politicians. No one is aboveboard as far as Malik Riaz is concerned. He is institutionalized corruption.”

If poverty and fear of incarceration are out as Hussain’s motives — what then? There remains a simpler, darker explanation for his actions. Delivering headline-generating terror convictions put the American government in his debt and gave Hussain something priceless: a sense that he did not have to answer to the law.

On the witness stand in the Newburgh trial, he acknowledged a litany of seemingly criminal acts, from tax evasion to bankruptcy fraud, much of it committed while he was in danger of deportation. “He just sat up there and smirked,” says Gombiner. Some found Hussain’s manner unnerving. While many people would be distressed by the work of setting someone up to commit a federal crime, he seemed to enjoy it. The jury watched as he lounged with his targets on a safe-house couch and drove around with them in his Hummer, making jokes.

Gombiner, though, finds Hussain’s lack of compassion less troubling than the conduct of the FBI and the prosecution, “who were so anxious to believe they had found something.” He was shocked by the FBI agents’ credulousness. Perhaps the second-most-riveting testimony of the trial came from Hussain’s handler, Robert Fuller. The special agent was part of the FBI team that is considered to have missed opportunities to thwart the 9/11 attacks. Hussain’s handiwork, in contrast, helped Fuller seem like a hero. In front of the Newburgh jury, the agent theatrically unzipped a canvas bag that contained what looked like a powerful bomb. Hussain had helped the defendants plant the device, which was harmless, at a synagogue in the Bronx.

Michael German, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice who spent years investigating terrorism for the FBI, told me that from the government’s point of view, an informant who is deceptive and transactional is neither unusual nor frowned upon. “Based on his documented criminal history and success in recruiting people into sting operations, the FBI clearly knew they were utilizing a talented manipulator,” German says of Hussain.

As Hussain’s mutually beneficial collaboration with the FBI continued, he diversified his business interests around Albany. In 2012, he opened Prestige Limousine. As recently as 2016, he was enjoying the FBI’s favor. One day that year, Horayra Hossain, a 19-year-old cabdriver, booked a room at the Crest Inn. His father, Mohammed, was the pizzeria owner in the Albany entrapment scheme and had been in prison for ten years. As Horayra was checking in, he recognized Shahed Hussain behind the counter. He considered what to say, walked away, then returned.

“Do you know who I am?” Horayra asked.

Hussain smirked and said no.

“You should remember me,” Horayra said. “It’s how you’re living lavish. I wonder how you sleep at night.” He mentioned his father’s case.

Still smirking, Hussain said he was mistaken. The confrontation was brief, and Horayra left. A day later, he got a call from the FBI. He never bothered Shahed Hussain again.

The Schoharie crash was a major disaster — a level-D mass-casualty incident — and fell under the jurisdiction of the National Transportation Safety Board. The day after everyone died, October 7, 2018, a rapid-response NTSB “go team” arrived, led by the agency’s chair, a courtly southerner and former US Airways pilot named Robert L. Sumwalt. During his nearly 15 years at the agency, it had investigated plane crashes, bridge collapses, boat sinkings, train derailments, and hot-air-balloon mishaps. Widely praised for its scrupulous, above-the-fray independence, the NTSB typically gets immediate, unfettered access to the scene of any accident involving a vehicle. In Schoharie, a visibly shaken Sumwalt gave a press conference — then discovered he had been frozen out of the investigation.

The New York State Police had taken charge. It moved the Excursion to its headquarters, and for the next week, Sumwalt’s investigators were forced to stand in a pen at a distance as troopers took it apart inside a tent the NTSB had helped pay for. The agency took the extraordinary step of going to the media to complain but even then gained little ground.

Publicly, the person responsible for excluding the agency was Susan Mallery, Schoharie County’s district attorney. Mallery, 54, whose father was DA before her, presides over one of the smallest prosecutor’s offices in the state, with a docket mainly of incidents along local roads. From the beginning, Mallery was viewed as “overmatched,” says Casey Seiler, the editor of the Times Union, and her battle with Sumwalt — in which “the state police appeared to work with the DA to thwart the NTSB,” as Seiler puts it — helped to create an atmosphere of secrecy and mistrust. Why was the independent expertise of the premier transportation-safety body in the U.S., if not the world, so unwanted?

Mallery avoided the press. More than once when a reporter cornered her, she resorted to hiding in her office. And she became especially unreachable when word began to spread last spring that Nauman Hussain, facing 20 charges of criminally negligent homicide and second-degree manslaughter, might never spend a day in prison.

Much of what the community has learned about the incident has come from one person: Larry Rulison, a baby-faced reporter for the Times Union. Rulison primarily covered business, but on the Monday after the crash, an editor asked him to field a call from a former employee of the New York State Department of Transportation. The caller had the Excursion’s DOT records, which showed a long history of mechanical trouble. Rulison has since written more than 175 articles, many based on documents exposing government agencies’ records of leniency toward the Hussains.

“I like finding records,” he says. “It takes time. You have to drive to the courthouse, and you have to know which door to go in. And then you have to be nice. A lot of reporters are jerks.” Rulison’s obsessive reporting — largely undertaken in the small hours, on his wife’s computer in the family playroom, after filing his quota of regional business dailies — has added layers of intrigue to the limo story. “Larry goes down rabbit holes,” says Kevin Cushing, whose 31-year-old son, Patrick, died in the Excursion. “And he gets rabbits.”

Rulison solved one of the bigger mysteries of the case when he located Shahed Hussain, who had gone missing, leaving Nauman to face the fallout from the crash. It was thought that Shahed had traveled to Pakistan in the middle of 2018, but when a family of some of the victims hired a process server specializing in tracking down litigants abroad, the server came up empty. From his basement, Rulison started searching Facebook “for, like, literally every random picture from Lahore for hours and hours a day,” he says. He eventually found a photo of Hussain in front of a building there. (Hussain has never responded to any of Rulison’s requests for comment, nor to mine.)

Rulison’s reporting demonstrates a pattern: The Hussains compulsively ignore rules and regulations, especially in matters of safety, yet never face consequences. He believes it suggests help from high places. Take the family hotel, he says, which was run by Haris Hussain, Nauman’s older brother, and racked up code violations. Raw sewage flowed out of the flimsy cabins into a muddy field. Electrical wiring and gas lines lay exposed. There was $30,000 in unpaid property taxes. Somehow the hotel wasn’t shuttered by tax collectors or health inspectors — not even after a 5-year-old fell into an unsecured septic tank and nearly died, nor after a fatal shooting on the premises. Only when the crash brought more scrutiny on the Hussains was the hotel condemned.

Prestige Limousine was an “outlaw limo company,” Rulison says. The Hussains avoided a state rule mandating tougher inspections for extra-large vehicles like the Excursion by falsifying reports, lying about its alteration by listing its seating capacity as 11 one year, eight the next, and ten the year after. Prestige never obtained operating authority, a state requirement for certain businesses that transport passengers. “When they got caught, they just blew it off and kept operating,” Rulison says. The company disregarded state inquiries about whether it drug-tested its drivers, as required by law, and its out-of-service rate — how often inspectors deemed its vehicles unsafe to drive — was 80 percent, more than 13 times the industry average. “Why didn’t they just take the stupid keys away or the plates? No one ever wanted to touch those guys,” says Rulison.

“Things always seem to work in their favor,” he adds. “They get a lot of mysterious breaks.” In 2014, Nauman and Haris Hussain were pulled over on Interstate 787. According to the police, Haris, who was driving, had a revoked license with 28 suspensions. Both were brought to a station where officers learned that the brothers had been ticketed more than 70 times and that Haris had repeatedly used his brother’s identity to avoid arrest. (Both Haris and Nauman go by multiple names. Nauman often uses “Arslan” and “Shawn.”) This resulted in a first-degree felony charge of aggravated unlicensed operation of a motor vehicle, but it was eventually dropped. “The judge in the limo case said something like it was the longest driving record he’d ever seen,” says Rulison. “It bothered him. It bothers everyone. I have to wrestle it off me. It’s the specter of something higher up. I just wonder if the treatment of Shahed Hussain was because of his work with the government and if that contributed to the crash. I always come up against people who said he’d flaunt that he’s FBI and would be like, ‘Stay away from me. Don’t hassle me. Don’t you know who I am?’ ”

Rulison says he is sustained by calls from former state employees and other knowledgeable sources wanting to discuss the crash. “Everyone would say that this just doesn’t make any sense,” says Rulison. “These were over-the-top violations.” As he pursued the Hussains, he began to feel worse and worse. In the summer of 2019, the then-48-year-old father of two checked into a hospital. His appendix had burst and sprayed a rare malignant cancer all over his abdomen. He took two months off for a procedure in which a surgeon used his fingers to peel tumors from Rulison’s organs, then he resumed filing stories. Chemotherapy numbed his fingers and addled his brain, but when he went to court, he found he could face the families of the crash victims a little easier. “I was like, ‘My life sucks right now too,’ ” he says.

Many of the Schoharie families have spiraled. Rich Steenburg, who lost his two sons, Axel and Rich Jr., was so destroyed by the crash that his family didn’t realize he had suffered a series of strokes. “Now he doesn’t remember having children,” says his former wife, Janet. “On the days he does remember, it’s October 6, 2018, and he is just hearing of the boys’ accident.” Beth Muldoon lost her son Adam Jackson and his wife, Abby, and retired from her job to raise the couple’s two daughters. Now 4 and 7 years old, the girls “lost their mom, their dad, four aunts, and two uncles,” says Muldoon. “Also a godfather.” Just before the crash, the Jacksons had moved into a house on the same block as Muldoon. For a year afterward, she says, she had to drive around the block in order not to pass her son’s house “because one of the girls would freak out. She thought we were hiding her parents and wouldn’t let her go see them. Or they’d see their cars in the driveway and say, ‘Mommy’s home! Daddy’s home!’ And then they would get really angry at us.”

The NTSB published its full report on the crash in fall 2020. It remains the definitive statement on the disaster despite the difficulties agents had accessing the scene. Addressing the public at an online hearing, board members struggled to contain their fury. Much of it was directed at the Department of Transportation, which knew Prestige was a threat — the report counted 32 times the agency had interacted with the company — and failed to act. But the deepest outrage was reserved for the Hussains. “Prestige,” vice-chairman Bruce Landsberg said, his face glowing red on the screen. “I can’t say enough negative about their disregard for human life.”

As the families waited for the district attorney to prosecute Nauman Hussain criminally, they considered their options for a civil lawsuit. The NTSB concluded that the state’s “ineffective oversight of Prestige” had been a probable cause of the deaths, but it is extremely hard to sue the government for a disaster like the one in Schoharie. In 2005, in a similar case just 60 miles away, a tour boat on Lake George capsized on a clear day, killing 20 out of 47 passengers, most of them senior citizens. The NTSB placed heavy blame on lax inspection requirements, but when victims’ families sued, a court ruled that the state enjoyed governmental immunity. Essentially, no matter how badly the people entrusted with protecting the public screw up, their failure has no consequences.

That left the dozen or so lawyers representing families of the Schoharie victims searching for someone else to blame. The Hussains had taken out an insurance policy on the Excursion, but it was for only $500,000, or $25,000 per death. The Crest Inn was worth perhaps $1 million — again, not much when split 20 ways. There was, however, a tantalizing target in Malik Riaz, the billionaire relative. The Times Union helped reveal that he had purchased the Crest Inn in 2010. The Hussains mixed limo and hotel work by storing vehicles on the property and using its address for both businesses, which prompted the Schoharie litigants to name Riaz as a co-defendant in civil suits. The case is considered a long shot. “Malik didn’t know anything about the operations,” one of his lawyers says. In a deposition last year from Pakistan, where he lives, Riaz said he rarely spoke to his brother and hadn’t seen him since the limo crash.

Another deep pocket materialized as the Schoharie district attorney looked into Prestige’s records. Over the years, the Hussains often took the Excursion to Mavis Discount Tire, a national chain, for inspections and repairs. They shouldn’t have: The branch wasn’t authorized to inspect vehicles that large. According to the DA, a Mavis manager admitted to inaccurate billing practices, “where certain services were substituted on invoices for ones actually performed,” including for work done on the Excursion. Nauman Hussain had been billed for a brake repair that was not performed as invoiced. Although the NTSB and a forensic investigator hired by the state police separately concluded the limo had crashed because of Prestige’s “egregious disregard for safety” and “neglect of mandated commercial-vehicle inspections and maintenance,” the Mavis disclosure turned the company into a target, one with the resources to deliver substantial compensation to victims’ families. The chain was recently acquired by a private-equity group for $6 billion. (Mavis maintains that it “bears no legal responsibility for this tragedy and the events that led up to it.”)

The revelation also gave the Hussains, who had recently hired Joe Tacopina, one of the most prominent defense lawyers in the U.S., a potential escape from prosecution. As Casey Seiler said, “Mavis blows a hole in the prosecution’s case.”

The criminal case against Nauman Hussain concluded on a Thursday afternoon in early September. Anticipating an angry and overflowing crowd, court officials converted the Schoharie High School gym into a makeshift courthouse. A bomb squad swept the locker rooms and the cafeteria, and police officers watched as 100 or so people filed in. The victims’ families, wearing sneakers, T-shirts, and hoodies, occupied a space near a podium. The Hussain entourage wheeled in smartly, shoes shined and cuts faded, escorted by a pair of bodyguards. Nauman took his seat at the defense table and stared at the parquet floor, flanked by Tacopina and his other lawyer, Lee Kindlon, both wearing massive gold watches. Nauman’s girlfriend, Melissa Bell, came in clutching a Louis Vuitton purse. Haris Hussain slouched so far back in his folding chair it groaned.

Judge George R. Bartlett III presided from a dais backed by championship banners for wrestling and volleyball. “We are all here today hoping for justice,” he told the courtroom. For almost three years, Bartlett had presided without urgency, allowing repeated delays and doing little to intercede in the dispute between local officials and the NTSB. Now he held his head in his hands, wept, and pleaded with the victims’ families to understand why he was allowing the district attorney to broker a plea deal in which Nauman Hussain would serve zero days in prison.

“I understand that many people, with good reason, feel the proposed sentence here is way too light. Twenty people are dead. How could the justice system even contemplate a sentence that does not impose decades of incarceration?” said Bartlett, reading haltingly from a statement in a tone that grew increasingly detached, as if the author were a mere observer in his own courtroom. “I have given it many hours of thought. It just does not seem right that 20 people are dead and the defendant receives a sentence of probation and community service.”

Bartlett turned to address the victims’ families directly, his voice coming over the gym’s tinny PA explaining why he had accepted the plea agreement the DA had brokered with the defense. Mavis had “weakened the district attorney’s case,” he said. “The evidence shows that Mr. Hussain paid Mavis for certain brake services, but such services were not described or reflected accurately on the Mavis invoices.” According to the agreement, Bartlett said, Hussain could not have foreseen the brake failure. He did not address the likelihood that the limousine had lost its stopping power because it was carrying so much passenger weight — much of it illegal because of the way the Hussains had falsely registered the vehicle. As for whether the Hussains bore any responsibility for the tragedy by taking the Excursion to an unqualified inspector, Bartlett said he simply deferred to the DA, who believed the actions did not “constitute a gross deviation from the standard for care that a reasonable person would observe.”

As the judge read, the families, who had known a deal was brewing, did not visibly react. When it was time for them to read victim-impact statements, it was clear their tempers were boiling over. “You are still a mass murderer,” John Schnurr, the brother of victim James Schnurr, said to Nauman Hussain. “You’ve turned my life into a living hell, pure torture,” said Kim Marie Bursese, mother of Savannah Bursese. “My life has fallen apart, and I’m afraid I won’t be able to get it started again,” said Kyle Ashton, the stepfather of Michael Ukaj. The statements lasted three hours — a reminder of how many people had died.

Then an extraordinary thing happened. Continuing his efforts to convince the families that justice had been served, Bartlett told them what they were getting instead of the punishment many said they desperately wanted Nauman Hussain to receive. “By pleading guilty, the defendant will have admitted his criminal negligence under oath,” he said. “Such will allow this to be used in any civil action. Moreover, by pleading guilty, the defendant no longer has a Fifth Amendment right to remain silent. Thus, he can be compelled to testify in any civil actions.”

No one in the gym needed it to be fleshed out. Bartlett had teed up Mavis, which is now the focus of a number of lawsuits filed by the families. “It’s a way of saying, ‘There’s no justice coming out of this courtroom. If you want to get justice, go over there,’ ” says Kevin Luibrand, who added that “in 38 years of practicing law, I’ve never seen anything like that.”

Then the proceedings ended. The Hussains sped off in a black SUV. They had repeated the pattern again — acting in disregard for life and the law but suffering scant consequences.

While Tacopina expounded before TV cameras, I looked for Larry Rulison, who had locked himself out of his car and was wandering around. Chemo, I assumed. Rulison often said things like, “My brain isn’t right.” His body doesn’t work well either — he holds on to the railings when he climbs stairs — and I thought he might be struggling physically. But when I found him, he was alone in downtown Schoharie, walking away from the scene, distraught.

“I’m shattered,” he told me. “I guess I have no idea how painful this has been to those families. I thought I knew emotional pain. I thought cancer was tough.” I offered him a ride, but he said he was going to type up an account of the day on his phone, find someone to break into his car, and drive home.