These days, Pete Buttigieg is concerned about the future of democracy. “I don’t think it’s an accident that the last time fascism was fashionable in certain corners of this country’s political class, one of the things they said for Mussolini is he made the trains run on time — it was a transportation example,” he tells me in his spacious office overlooking the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C.

“Which by the way, importantly, was not actually true,” he is quick to add, his eyes suddenly widening. He brings up China and the narrative of “their order versus our chaos,” which the Chinese bolster with enormous infrastructure investments. “Part of what motivates me in this work is that the workaday things that we’re focused on, it’s right back to some really profound issues we’re dealing with in terms of what kind of country we’re going to be,” Buttigieg says. “It’s about whether democracy can deliver.”

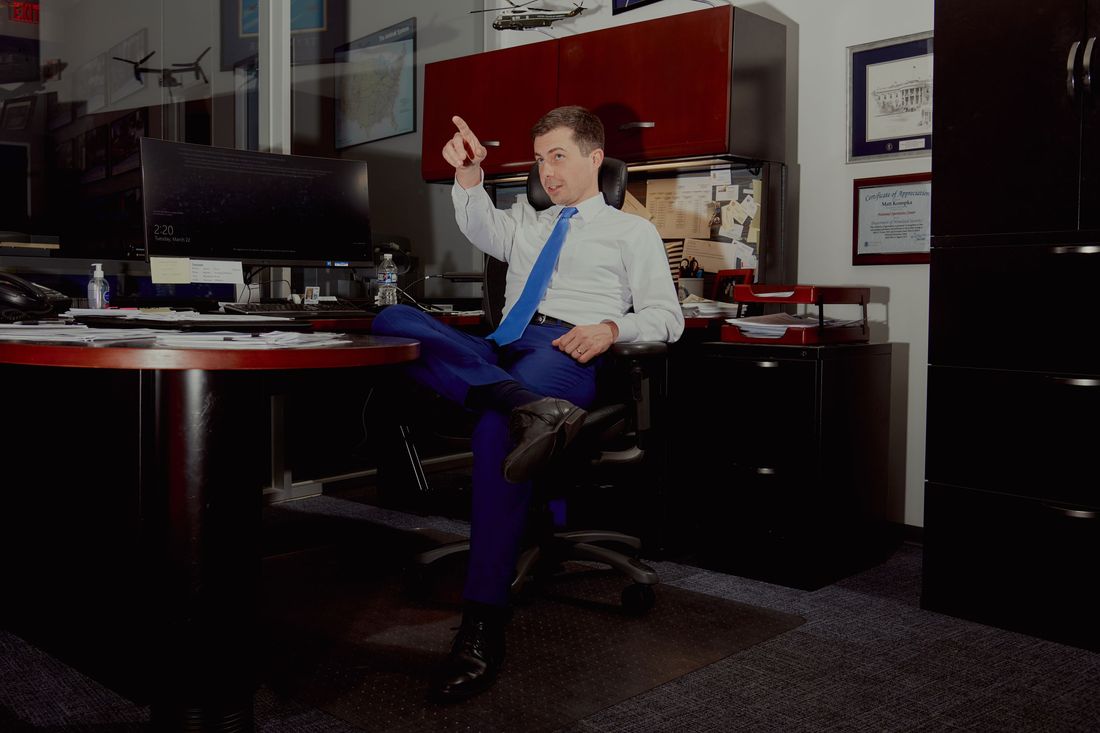

Buttigieg, in his light-blue necktie and crisp white shirt, hasn’t had many acquaintances, let alone journalists, in his D.C. office since becoming Joe Biden’s secretary of Transportation in 2021. COVID locked people behind Zoom screens, and Buttigieg, perhaps the administration’s most adept political animal, had been left to evangelize for transportation and infrastructure virtually.

That has begun to change for the newly minted 40-year-old and father of twins, who is not only hobnobbing more in Washington but recently visited South by Southwest and packs a busy schedule of out-of-town events. His office, in the chic D.C. Navy Yard neighborhood, has few personal touches. A Notre Dame coaster, sitting next to a newsletter provided by a longshoreman union, is a small reminder of where he came from.

In a year of woe and confusion for Biden — the war in Ukraine seems to be boosting a president who has been bogged down with Donald Trump–like approval ratings for many months — it has been Buttigieg who is out front and unruffled, the public face of a trillion-dollar infrastructure package that might be the president’s defining domestic-legacy item. At a time when other members of the Cabinet are struggling to escape the administration’s travails, Buttigieg has proved himself to be both a dogged defender of the president and an irrepressibly buoyant figure with a following all his own, as likely to appear in People magazine with his husband, Chasten, and the twins as on Meet the Press.

Right time, right place for Buttigieg, who will always be known, to a certain crowd, as Mayor Pete. The former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, has been marked for stardom since his Harvard days, shooting to national fame with a surprisingly viable presidential campaign in 2020. In New Hampshire, Biden cut a blistering ad mocking Buttigieg’s small-town roots — comparing the former veep’s revitalization of the U.S. auto industry with Buttigieg’s revitalization of South Bend’s sidewalks — but Buttigieg still managed to strategically endorse Biden not long after, helping consolidate votes against a surging Bernie Sanders.

If the Biden campaign seemed, at times, to subsist on whatever terror and rage Democratic voters could marshal against Trump, Buttigieg’s bid was a small taste of what Biden’s old boss had once offered curious Iowans. An openly gay military veteran making his own soaring case for aspirational liberalism, Buttigieg could captivate a packed gymnasium like Barack Obama and soon became a favorite of White House alums like David Axelrod.

Now on everyone’s shortlist of possible presidential contenders, Buttigieg is reflective, if circumspect, about his future. “I don’t know if I’ll run for office ever again,” he says, pausing carefully before answering yet another question about what comes next. “It’s there,” he acknowledges of the political chatter, particularly talk of a future clash with Vice-President Kamala Harris, who has recently been the subject of stories of palace intrigue in the press. (According to a new book by New York Times reporters Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns, Biden’s staffers have been rolling their eyes at the “First World problems” that seem to preoccupy the vice-president, including an unflattering cover shoot for Vogue.) “The main thing is just not to be distracted by it,” Buttigieg says. “There’s literally no time.” However, he admits he offers communication advice when requested to a White House that has struggled to convey its accomplishments to voters.

What he has missed about the campaign trail, he says, is “being in the room, watching faces rise and fall as I learn what really resonates.” But he is sure to diplomatically add, “It’s rewarding to be campaigning not for yourself but for an idea.”

That idea is infrastructure, a bipartisan staple of Washington that, in its nuts-and-bolts nerdiness, seems ideally suited to a politician who has always embodied the straight-A student hungry to answer the next question. Transportation policy genuinely excites Buttigieg, who gained a small degree of fame among wonks for his successful pedestrianization of South Bend. He has rolled out an ambitious plan to drastically slash traffic fatalities nationwide. He is outspoken about the environmental and sociological degradation that certain highway systems have brought to communities of color. Technocrats have great sway with him: Polly Trottenberg, his deputy, was the long-serving New York City DOT commissioner and has been given broad latitude to pitch and implement policy.

Most important, Buttigieg commands money. A Reuters analysis of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed by Congress late last year, estimates that around $126 billion of the $660 billion allotted to the DOT for the next five years will be for new spending. Competitive grant programs will allow him to choose where the cash flows. “Building infrastructure is like building cathedrals,” he says. “It’s very rare the person who lays the cornerstone gets to be the person who cuts the ribbon.”

Democratic politicians still bristling from the Trump years, when the penny-pinching Elaine Chao ran the department, sing hosannas for Secretary Pete. “My God, it’s night and day,” says New Jersey governor Phil Murphy. “He’s a guy who understands what it’s like being chief executive. If you’re a governor, you’re automatically on a similar wavelength with him. He’s lived in my shoes, and to some extent I’ve lived in his.”

Infrastructure money will endear Buttigieg not only to powerful Democrats across the country but to voters. For example, it will go a long way toward building a new rail tunnel between New York and New Jersey, a project Chris Christie scuttled and Trump failed to revive. For Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, Buttigieg was a revelation because he was willing to listen to her pleas to incorporate funding for disability access to mass-transit systems. “He was as good as his word,” she says. “That’s really critical. A lot of folks, a lot of principals, they want to take the picture and don’t follow through.”

Transit experts are pleased with Buttigieg but still waiting for a greater vision of what transportation should look like in the U.S. There are hard rules around how federal money is spent; much of it must go toward car-friendly highway-expansion projects.

“What the administration has been focused on has been funding, not policy,” says Beth Osborne, the director of Transportation for America and a former high-ranking official in the Obama DOT.

The pandemic-induced supply-chain crisis and inflation have presented steep challenges for Buttigieg, but he is calmly defensive of the administration’s performance thus far. “We’re doing a lot,” he says. “It’s worth noting that if you had looked at some of the coverage in October, you would have thought that the holidays were basically canceled, but we got through them.”

More complications loom. Spirit and Frontier, two low-cost airlines, are seeking to merge, which would create another enormous carrier in an already consolidated industry that pretty much everyone hates. Buttigieg has the power, along with the Department of Justice, to derail the merger. For now, he’s noncommittal. “It has my attention, obviously,” he insists.

Buttigieg claims he’s content in D.C. managing a massive federal bureaucracy and not campaigning for a promotion. Gazing out the window at the cranes cutting across the sky and the traffic flowing quietly over the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, he considers this new pace of life. “I remember rejoicing any time, when I was running, that I got to be in the same hotel room for two nights in a row because that meant at least I didn’t have to pack my toothbrush.”

“Now, one, two trips a week, maximum. It’s more civilized.”