This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Coquille, on the Oregon coast, is a two-stoplight town where mist rolls off the Pacific and many of the 4,000 residents work in lumber and fishing. On the night of June 28, 2000, a 15-year-old named Leah Freeman left a friend’s house and set off on her own. She was seen walking past McKay’s Market, the credit union, and the high school, but she never made it home. At a gas station, a county worker found one of Leah’s sneakers.

The local paper published Leah’s school photo: big smile, mouthful of braces. Police and a donor put together a $10,000 reward for information leading to her safe return. K-9 units swept the school grounds, and police set up roadblocks and interviewed motorists. On its sign, the Myrtle Lane Motel posted a description of Leah. A month later, the message was replaced with Job 1:22: “The Lord gives. The Lord takes.” A search party had found Leah’s body at the bottom of an embankment, severely decomposed. “We prayed for her to return,” the motel manager told a reporter. “And now we can pray for whoever did this to be caught.”

But the killer was not caught. The police had initially treated Leah as a runaway before mounting a search, and when the FBI and state police finally arrived, investigators were too far behind. They never recovered. As months turned into years, Coquille police dwelled on one suspect whose story never quite made sense to them: Nick McGuffin, Leah’s 18-year-old boyfriend. Friends had seen them argue. Police said he switched cars the night she vanished and flunked a polygraph. The hunch was there, but the physical evidence wasn’t.

In January 2010, a new team of detectives and a prosecutor flew to Philadelphia to pursue a last-ditch option: to present the case to a league of elite investigators called the Vidocq Society, which met once a month to listen to the facts of cold cases and sometimes venture instant insights. The group’s co-founder, Richard Walter, was billed as one of America’s preeminent criminal profilers, an investigative wizard who could examine a few clues and conjure a portrait of a murderer.

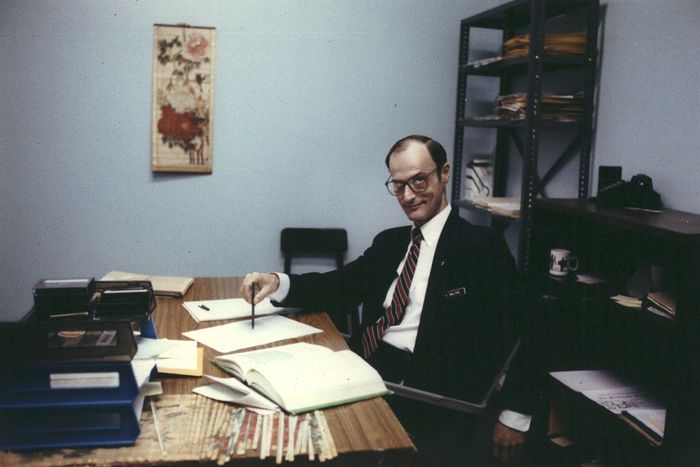

Walter was tall and gaunt with a hard-to-place, vaguely English accent. He favored Kools and Chardonnay, and he was never photographed in anything but a dark suit, a tiny smile often curling at the corner of his mouth. His public profile was about to explode. A publisher was finalizing a book about the Vidocq Society, The Murder Room, which detailed Walter’s casework on four continents and claimed that at Scotland Yard he was known as “the living Sherlock Holmes.”

In Philadelphia, members of the Coquille team presented Leah Freeman’s murder to the Vidocq Society. Later, at a private dinner, Walter dangled before them a tantalizing profile that suggested the killer was indeed McGuffin, the boyfriend they had suspected all along. Soon, Walter traveled to Coquille and examined crime scenes with the police chief, trailed by a camera crew from ABC’s 20/20.

Building on the momentum of Walter’s visit, the authorities arrested McGuffin and charged him with killing Leah. As he awaited trial, he watched the 20/20 episode about his case from the Coos County jail. There on TV was Walter, a man he had never met, all but accusing him of murder. “It’s sweet revenge,” Walter said with a grin. “And I take great personal satisfaction in hearing handcuffs click.” McGuffin was convicted and sentenced to a decade in prison. In the years to come, he would often sit in his cell and wonder: Who was that thin man smoking on the screen?

Richard Walter is many things and little that he claims. Since at least 1982, he has touted phony credentials and a bogus work history. He claims to have helped solve murder cases that, in reality, he had limited or no involvement with — and even one murder that may not have occurred at all. These lies did not prevent him from serving as an expert witness in trials across the country. His specialty was providing criminal profiles that neatly implicated defendants, imputing motives to them that could support harsher charges and win over juries. Convictions in at least three murder cases in which he testified have since been overturned. In 2003, a federal judge declared him a “charlatan.”

Walter refused several requests for an interview. “You have earned one’s distrust that merits severing any contact with you in the future,” he wrote me, veering into strange pronoun usage. “Under no circumstances would himself cooperate in your suspicious activities.”

Many of his misdeeds were a matter of record before he ever stepped foot in Coquille. And yet Walter continued to operate with impunity, charging as much as $1,000 a day as a consultant. America’s fragmented criminal-justice system allowed him to commit perjury in one state and move on to the next. Journalists laundered his reputation in TV shows and books. Parents desperate for closure in the unsolved murder of a son or daughter clamored for his aid. Then there was Walter’s own pathology. He so fully inhabited the role of celebrated criminal profiler he appeared to forget he was pulling a con at all.

In Richard Walter’s telling, he was fated for a grim life studying criminals. But schoolmates who grew up with him in the rolling orchard country of 1950s Washington State remember an outgoing, popular kid who liked the piano and led the prayer band at a Seventh Day Adventist boarding school. In September 1963, at the age of 20, he married a former classmate and briefly took a job at a funeral home. (“He didn’t want to work with any old, stinky bodies,” his brother recalled in an interview.) After ten months, his wife filed for divorce, citing “mental cruelty.” What happened over the next several years is unclear. When asked in a recent deposition where he lived and worked during that period, Walter said, “I don’t remember.”

Walter resurfaces in the public record in 1975, when he graduated from Michigan State University with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in psychology. He got an entry-level position as a lab assistant in the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner’s Office. He was 33 and making roughly $3 an hour washing test tubes. He considered a doctoral program but instead took a job in 1978 as a staff psychologist at a place where he’d be able to see patients without any further qualifications: Marquette Branch Prison on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Walter’s rapport with prisoners was poor — he often conducted interviews through a closed steel door — and he could be petty. An inmate sued Walter after he refused to pass along a dictionary sent by his mother. Two psychiatric experts and a federal judge questioned his ability to diagnose mental disorders and render basic mental-health services. Eventually, Walter’s duties largely involved conducting intake interviews with inmates. “What I call meatball stuff,” says John Hand, who also worked in the state prison system as a psychologist. “Talk to them for a little while, make sure they’re not totally crazy.”

Away from the prison, though, Walter presented his job as giving him unique insights into the criminal mind. He became a regular at conferences hosted by the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, which was rising in stature on the strength of specialties like hair microscopy, bullet-lead analysis, and criminal profiling.

Profiling was especially hot. The FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit was going from fringe to mainstream: The profilers there had consulted on fewer than 200 cases in all of the 1970s, but by the middle of the next decade, they were providing hundreds of assists per year. The unit began attracting big personalities. “Where there are stars, there are wannabe stars,” says Park Dietz, a forensic psychiatrist who has worked with the BSU. “Those with big egos will often gravitate to those centers of narcissistic glory.”

In 1982, Walter became a full member of the AAFS, a powerful credential. That year, for the first time, he would try on his invented persona in a courtroom.

Robie Drake was wearing military fatigues and carrying rifles and hunting knives when he left his home in the Buffalo suburbs. It was just before midnight on December 5, 1981, and the 17-year-old headed to an area of North Tonawanda filled with abandoned vehicles. He took aim at a 1969 Chevy Nova and fired 19 rounds into the passenger-side window. From inside the car, he heard groaning. The location was also a lover’s lane, and his bullets had struck Stephen Rosenthal, 18, and Amy Smith, 16. Drake then stabbed Rosenthal in the back. Two police officers on a routine patrol spotted Drake stuffing Smith’s body into the trunk of the Nova.

The case appeared open and shut. But the prosecutor, Peter Broderick, saw weaknesses. Drake insisted it had all been a mistake, and his reasons were just plausible enough to imagine holdouts on a jury. The scene had been dark. Drake said he’d shot the car for target practice, thinking it was empty, and panicked when he heard Rosenthal and stabbed him to make the noise stop. However unlikely that sounded, Broderick lacked a clear motive, and intent would be the sole issue separating a murder conviction from a lesser charge of manslaughter. “All I needed was some reasonable explanation for why this thing happened,” Broderick later said.

Broderick suspected Drake’s motive was sexual, and he hired Lowell Levine, a forensic odontologist, to testify that faint marks on Smith’s body were signs of postmortem biting, which was possible evidence of a sex crime. Levine suggested that to firm up that angle, the prosecutor should bring in another expert — someone he’d recently met at an AAFS conference. Two weeks later, Broderick drove to the airport and picked up Richard Walter.

On the stand at Drake’s trial, Walter related an impressive — and fictional — résumé. He falsely claimed that at the L.A. County Medical Examiner’s Office, he had reviewed more than 5,000 murder cases. Walter also said he was an adjunct lecturer at Northern Michigan University (he had spoken there informally, possibly just once), wrote criminology papers (he had never published), and had served as an expert witness at hundreds of trials (he’d testified in two known cases — about a simple chain-of-evidence question and in a civil suit against a car company).

Walter told the jury that Drake had committed a particular type of “lust murder” because he was driven by “piquerism,” an obscure sadistic impulse to derive sexual pleasure from penetrating people with bullets, knives, and teeth. Drake’s attorney told the court that he could not find any expert who had ever heard of piquerism, but the judge denied his request for more time to find a rebuttal psychologist. Drake was convicted of second-degree murder. Back in Michigan, Walter sent Broderick an invoice. For securing two consecutive terms of 20 years to life, his fee was $300.

The trial was the end of Robie Drake’s freedom and the beginning of Walter’s new career. He continued testifying in occasional murder trials and inflating his qualifications. By 1987, when he took the stand in State of Ohio v. Richard Haynes, he held himself out as a superstar in his field, telling the prosecutor that he was one of just ten or so criminal profilers trusted by the FBI.

Walter lectured widely, giving speeches like “Lust, Arson and Rape: A Factorial Approach” and “Anger Biting: The Hidden Impulse.” Audiences loved his entertaining, wry style. “His story, as many of Richard’s, has to be heard from his own mouth,” wrote an amused attendee after Walter’s presentation at a 1989 conference hosted by the Association of Police Surgeons of Great Britain. “It would lose all by repetition by another.”

Walter was about to get a new venue for his theatrics. According to one version of events, it was around this time, at an AAFS convention, that Walter met Frank Bender, an eclectic Philadelphia artist who had begun a sideline in forensic sculpture, reconstructing busts from decomposed bodies. Bender was plugged into the local law-enforcement scene, and he introduced Walter to Bill Fleisher, a Customs agent. At a diner, the three talked about cases until the sun set. Standing on the sidewalk in the cold, they had the idea to organize a bigger confab — a group of law-enforcement professionals who would meet regularly and talk murder over lunch.

“What,” Bender asked, “are we going to call our club?”

The namesake of the Vidocq Society — which Walter, Bender, and Fleisher established in Philadelphia in 1990 — is Eugène-François Vidocq, a 19th-century French criminal turned detective who is considered the father of modern criminology. Some of the club’s early members had impressive jobs as Customs agents, IRS investigators, and U.S. marshals, but there were also advocates of dubious fields like polygraphy and statement analysis. Few had extensive experience with homicide. That didn’t matter much at first, as the group spent its initial meetings — usually held at Philadelphia restaurants or social clubs — discussing historical cases like the Cleveland “Torso Murders” of the 1930s. But soon the members began taking on more recent unsolved murders in which they might have a shot at catching a killer.

Criminal profiling was becoming a pop-culture sensation, thanks in large part to the 1991 blockbuster The Silence of the Lambs, which made $272 million and swept the Academy Awards. “It was a very exciting time,” says Jana Monroe, an FBI profiler who helped Jodie Foster prepare for her role in the film. “But the FBI didn’t like all the media attention.” The Vidocq Society moved into the vacuum, quickly notching write-ups in the Philadelphia Inquirer and the New York Times.

Reporters relished describing the three co-founders: Walter was the chain-smoking genius; Bender was the artist, conspicuous among the suits in T-shirt and jeans; Fleisher was the teddy-bear G-man, prone to tearing up during presentations. Hollywood began calling, as did network TV.

CBS’s 48 Hours came to a Philadelphia dining hall to watch the Vidocq Society consider the case of Zoia Assur, a 27-year-old who was found dead in the woods of Ocean County, New Jersey. Her fiancé, an ophthalmologist named Ken Andronico, suspected her death was not a suicide but murder, and a friend of Andronico’s had approached the organization for help. Fleisher presented the facts and concluded, in a thick Philly accent, “Now, our case begins.”

CBS correspondent Richard Schlesinger raced around the room to solicit theories. “Murder or suicide?” he asked club members as they tucked into plates of chicken Marsala. “Murder!” they blurted through full mouths. “We haven’t even gotten to dessert yet!” Schlesinger cried with delight. Walter told the camera that Andronico might have been the killer. “He’s playing that high-risk game of ‘Catch me if you can,’” he said with a smile.

Andronico — who had been more than a thousand miles away in Florida at the time of Assur’s death — watched the 48 Hours episode from his apartment with his mouth agape. Patients began canceling their appointments, and his medical practice was upended for years. He was never charged with a crime. (Retired Ocean County detective James Churchill dismisses the theory and the Vidocq Society’s involvement. “They never looked at the file, they never had any statements, they never had any medical records,” Churchill says. “I thought it was just preposterous.”)

Others were not so lucky. At the Vidocq Society’s April 1992 meeting, a Philadelphia homicide detective named Bob Snyder walked to a podium, opened a thick file, and presented the cold-case murder of Deborah Wilson, an undergraduate at Drexel University who had been killed after working into the night at a computer lab. Waiters served lunch as members viewed photos of the bloody crime scene and her foamy saliva, which indicated strangulation. Afterward, Walter offered an insight: Wilson’s sneakers had been removed, indicating that the killer had a foot fetish.

When police later searched the home of David Dickson, a security guard on duty the night of the murder, they found a collection of women’s sneakers and foot-fetish pornography. The press called him “Dr. Scholl,” and Dickson was charged with murder. In court, his attorney protested that the alleged motive was absurd. “This man is a sneaker sniffer, not a murderer!” he cried. But the prosecutor was Roger King, a powerhouse who claimed to have put more men on death row than anyone else in the history of his office. One jury deadlocked, but King won the retrial. Dickson was sentenced to life in prison.

The Vidocq Society pinned a medal on Snyder, and the club celebrated cracking a major case. But Walter was the real winner. His theory had led to the arrest and conviction. He would cite the case in media interviews for decades.

King died in 2016. Five years later, the Philadelphia Inquirer published a major investigation into his tactics, finding that he had routinely manipulated witnesses, withheld exculpatory evidence, and employed jailhouse snitches whose credibility he knew was suspect — including one, John Hall, who testified against Dickson. Hall’s wife had helped him fabricate testimony by sending newspaper clippings to him in jail. “Nothing he said was true,” she told the Inquirer. At least seven of King’s murder convictions have been overturned.

Dickson’s could be next. In the fall, his attorney filed a petition with the court arguing that King withheld or twisted information critical to Walter’s foot-fetish theory, including the possibility that the victim’s sneakers may not have been taken from the scene after all.

The Richard Walter story is not the case of an impostor who goes undetected, one misstep away from being discovered and exposed. Lots of people saw signs; few had incentive to do anything about it. Throughout the 1990s, he continued to work in the Michigan correction system as a psychologist, and word eventually got around about his profiling sideline. Some found the arrangement comical. “If he’s got an international reputation, why is he working in a prison for $10,000 a year?” Hand, his contemporary, says with a laugh.

Many others saw through Walter’s act. Retired FBI agent Gregg McCrary recalls that the Behavioral Science Unit once invited Walter to Quantico to ask him questions about inmate behavior. “The narcissism, I think, was obvious. He really thought he knew a lot,” McCrary says. The agents learned little, and he was not invited back. “Richard Walter is largely a poseur,” McCrary says. “What I say about Richard is he’s an expert at being an expert, at playing one and convincing people that he is.”

Walter’s victims struggled to get anyone to pay attention, even when they caught him in obvious lies. In 1995, Robie Drake still had decades to go on his sentence. From his maximum-security prison in upstate New York, he’d been digging into Walter’s résumé on an antiquated computer terminal. He had married a nurse 24 years his senior named Marlene, and she helped, requesting documents and contacting Walter’s former employers. They found the various ways in which Walter had perjured himself, but when Drake appealed, a court denied his motion without a hearing.

Marlene then sent the American Academy of Forensic Sciences a 13-page dossier of Walter’s inflations and outright falsehoods. Officials at the organization acknowledged in internal memos that Walter had padded his résumé, but they decided to reveal as little as possible about their internal deliberations. “We do have to worry about public appearances,” Don Harper Mills, a pathologist who was chairman of the ethics committee, wrote to his colleagues. In a February 1996 letter to Marlene, Mills delivered his verdict in a single paragraph. “Most of the issues do not involve the Academy’s Code of Ethics,” he wrote. “The Committee has concluded unanimously that there was no misrepresentation and therefore no Code violation.”

One reason Walter kept skating by is that defendants like Drake existed in an ethical twilight. He was a guilty man robbed of due process. An expert witness had lied, and he had perhaps spent more of his life in prison than was warranted because of it, but he had killed two teenagers. What was Walter’s perjury next to that?

Walter was also galvanized by support from an unimpeachable group: victims’ families. He spoke before the Parents of Murdered Children, a nonprofit that offers grief counseling and helps families lobby parole panels against early releases, and later joined the board. At the group’s annual conference, he granted private audiences to devastated parents. After years or decades of frustration with police and prosecutors, they appreciated Walter’s shared sense of anger, like when he said that some murder suspects should be handled with “seven cents’ worth of lead.”

Walter knew how to give delicious, cinematic quotes, and he cultivated his eccentricities for journalists and producers. He boasted of subsisting on cigarettes and cheeseburgers. He said that when the time was right, he would “lie down to quite pleasant dreams” using sodium pentothal. He once yelled at a suspect, “I’ll chew your dick down so far you won’t have enough left to fuck roadkill.”

The effect was irresistible. In A Question of Guilt, a Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys crossover novel published in 1996, the iconic teen detectives run into one another at a meeting of the Vidocq Society. Filmmakers courted Walter and his co-founders for years, taking them to dine at Le Bec-Fin. Walter told the Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin that a producer wanted Kevin Spacey to play him in a movie. In 1997, Danny DeVito’s Jersey Films purchased the Vidocq creators’ story rights in a deal worth as much as $1.3 million. (No film was ever made, Fleisher says, and the founders received a fraction of that amount.)

Money doesn’t seem to be what drove Walter. While his lifestyle had some flourishes — he slept in an antique Chinese bed and played Tchaikovsky on a 1926 Chickering grand piano — he mostly lived frugally. He drank bottom-shelf wine and drove a succession of Crown Victorias into the ground.

The relish with which he played the role of a genius profiler points to another, stronger motivation: ego. “He totally cannot be in a social setting where he is not the center of attention,” says a longtime Vidocq Society member. At meetings, Walter tended to speak last, rendering his judgment to a roomful of nodding heads. “He’s been hyped so much by the leadership in the organization,” says the member. “Nobody challenges him.” (A spokesperson for the organization disputes this.)

It’s difficult to look at Walter’s body of work — real or claimed — and not notice some preoccupations. Of the more than 100 papers and presentations listed on his résumé, roughly a quarter pertain to homosexuality or sex crimes. A representative example, “Homosexual Panic and Murder,” is a case study based on interviews he conducted with an inmate who had murdered a man and then cut off one of his testicles.

“The homosexual: not really a man,” Walter testified once in a murder case. “He is a discount person; therefore, if I need to be great, if I need to satisfy my ego, if I need to satisfy my needs for power, if I need to surmount, if I need to have a demonstration of my power, well, what better way to do it?”

In September 2002, two police officers from Hockley County, Texas, flew to Philadelphia for the society’s help in solving a cold case. According to a 2003 account in Harper’s, during a private meeting after the luncheon, Walter in lurid detail pronounced the Texas murder a case of “homosexual panic” — one man suddenly killing another after a tryst. He and Frank Bender invited the detectives out to dinner, where Walter became increasingly intoxicated, according to the magazine. “They’re making a movie about us,” Walter said, toasting with his Chardonnay. “Frank’s the pervert and I’m the guy with the big dick!”

Walter continued to press his theory. “It seemed like it didn’t matter what the case was, he just thought it was some kind of sexual deviancy or homosexuality, which I disagreed with,” says one of the Texas officers, Rick Wooton. No arrest has been made in the case. Walter, he says, was no help.

In September 2000, Walter retired from the Michigan Department of Corrections at 57 and moved to Montrose, a town in Pennsylvania with a population of 1,300. “Everyone was falling all over him because of his reputation,” says Betty Smith, the former curator of the local historical society. Walter tells neighbors that he came to testify in a murder trial, fell in love with the town, and decided to stay. But two attorneys involved in the case say they don’t recall ever meeting him.

Walter took on more freelance work. When he arrived in small towns around America, his presence was front-page news. In at least seven separate cold cases, Walter spoke to local reporters and delivered his catchphrase — a warning to the killer that his arrest was imminent: “Don’t buy any green bananas.” Walter’s work did not lead to arrests in five of those cases. In a sixth, his favored suspect, a Catholic priest, committed suicide, and Walter gleefully claimed credit for his death.

Meanwhile, from his prison cell upstate, Robie Drake persisted in appealing his conviction. In January 2003, he finally got a win. Referring to Walter and his piquerism theory, a federal judge wrote that “the witness was a charlatan” and that “his testimony was, medically speaking, nonsense.” In a deposition that July, Walter was evasive as Drake’s attorney pressed him on the tasks he performed at the L.A. County Medical Examiner’s Office.

“What were you doing?” the attorney asked.

“Good question,” Walter replied.

“It’s the only question.”

By 2009, the Second Circuit decided it had seen enough: Walter had perjured himself with the prosecution’s knowledge. The judges ordered a new trial. Prosecutors used a technique for analyzing bullet trajectory to argue that Drake had been closer to the Chevy Nova than initially thought, suggesting he must have known people were inside. In 2010, a jury convicted Drake again. He had exposed Walter as a fraud, but for his troubles the judge extended his original 40-year sentence by an extra decade.

Throughout his career, Walter had benefited from the fractured nature of the American legal system. Especially in the years before digitized records, a public defender in one place suspicious of Walter would have trouble tracking him across jurisdictions. The Second Circuit’s ruling was harder to run from. Luckily for Walter, a reputation reset was on the way.

Several years earlier, the author Michael Capuzzo, who had written a best seller on shark attacks, had scored a blockbuster $800,000 advance for a book about the Vidocq Society. Publisher’s Weekly described it as “a true tale about a mysterious group of skilled detectives who use their skills to solve only the most despicable of crimes, led by a figure who seems to be a contemporary Sherlock Holmes.”

Later, another author, Ted Botha, sold a proposal for a book about Frank Bender and his forensic sculptures. He worried about Capuzzo’s three-year head start. And yet, as he reported, he never came across anyone who had spoken to Capuzzo. “I was quite amazed,” Botha says. “This guy’s gotten a wack-load of money, and there doesn’t seem to be anything happening.” Botha interviewed Walter but got a sense that something was amiss. He confined Walter to a handful of pages when he published his book, The Girl With the Crooked Nose, in 2008.

Capuzzo’s volume, The Murder Room, was published two years later. It was an instant hit and would go on to sell roughly 100,000 copies, despite purple prose that described Walter as “the angel of vengeance” and “the ferryman poling parents of murdered children through blood tides of woe.”

The book repeated and expanded on dozens of falsehoods in Walter’s résumé. In the Michigan prison system, he wrote, Walter could shut off hot water and put inmates on a diet of “prison loaf,” with three meals a day blended and baked into a tasteless brick. “You will learn to control yourself or I will control you,” he allegedly told them. But a prison spokesman disputes that a psychologist could leverage showers and meals in that way. “Maybe in Shawshank or something,” he says. “But not in real life.”

Walter also claims in the book that Michigan State hired him as an adjunct professor and that he collaborated with the university police to investigate gay twin brothers who fondled football fans without their consent outside Spartan Stadium. But a Michigan State spokesman denies that Walter has ever been employed by the school.

The book repeats Walter’s claim to have solved the notorious 1986 murder of Anita Cobby, a former beauty queen who was gang-raped and nearly beheaded in Australia. Detective Ian Kennedy, who led the investigation, tells me he has never heard of Walter. Other supposed feats are stranger still. Capuzzo details the murder of Paul Bernard Allain, whose boss, Antoine LeHavre, brings the case to the Vidocq Society. In a twist, Walter accuses LeHavre of killing Allain himself, the result of a homosexual affair gone awry. But Allain and LeHavre do not seem to appear in any legal or public-record databases. Capuzzo may have changed the names; he or Walter may have made up the whole story.

Bender and Fleisher grumbled to the Inquirer that Capuzzo had taken too much creative license. “There are parts of that book I know are not true,” Bender said. (He died in July 2011. Fleisher didn’t respond to requests for an interview.) But Walter joined Capuzzo on a nationwide book tour. “It’s fun to play detective,” said NPR host Dave Davies as he described the Vidocq Society on Fresh Air. “But they aren’t playing.”

Walter was in his glory. “There’s a price to pay,” he told listeners of his macabre life’s work. “I’m willing to pay it.”

Capuzzo did not respond to requests for comment. He has not written another book, and today he publishes a Substack promoting vaccine conspiracy theories. During a recent podcast appearance, he said that several years ago, he heard a voice in his head say, “I am here. Tell my story.”

By the time The Murder Room reinvigorated the myth of Richard Walter, a decade had passed since Leah Freeman’s murder. In Coquille, the candlelight vigils had grown smaller. Pink JUSTICE FOR LEAH hoodies spent longer intervals in the closet. Leah’s father died; her mother, Cory Courtright, regularly posted about the case on the message board Websleuths and interacted with amateur gumshoes, desperate for a break in the case. Nick McGuffin, now 28, had tried to move on. He’d had a daughter, graduated from culinary school, and become the head banquet chef at a casino in Coos Bay.

Coos County had a new district attorney named Paul Frasier, and he helped Coquille hire its next police chief, Mark Dannels, who committed to reopening the case. Dannels took down the old evidence boxes and assembled a cold-case team. Soon, they were flying to Philadelphia and huddling with Walter. Separately, an ABC producer had an idea: Wouldn’t it be gripping television to follow the Vidocq Society in the field? A team from 20/20 shadowed Walter in Coquille as he assisted the investigation of Leah Freeman’s murder, and the network built an episode around him and The Murder Room.

The killer, Walter told the camera, was “that muscle-flexing, Teutonic kind of braggart who thinks he’s John Wayne, who wants to be a bigger man than what he is.” He encouraged the police to focus on McGuffin. There was no new physical evidence, but Walter rearranged puzzle pieces that didn’t quite fit and crafted his own theory: McGuffin was a jealous boyfriend who hit Leah in the face and dumped her body in the woods.

Cops played tough for 20/20 producers as they tailed McGuffin around town, hoping to provoke him. “In my opinion, he needs to be poked at a little bit,” one officer said. Correspondent Jim Avila, who had reported from Beirut and the Gaza Strip, chased McGuffin’s car, asking him why he wouldn’t talk.

On August 24, 2010, police arrested McGuffin near his home. “Why do they think you did it?” an ABC producer asked as he was handcuffed in his chef’s jacket. “Because they have nothing else to go on and I’m the boyfriend,” McGuffin said.

Just what contribution Walter made to the case is now the subject of intense legal scrutiny. Paul Frasier, the district attorney, has insisted in a series of memos that he was suspicious of Walter, learned about the Robie Drake case, and resolved not to rely on him. Yet Walter’s fingerprints were all over Frasier’s eventual case at trial. In his closing argument, Frasier parroted Walter’s entire theory. And Mark Stanoch, who produced the 20/20 segment, worried that the coverage tainted the jury pool. “When you show up in a town of a couple thousand people with cameras, that dynamic can overwhelm the evidence,” he says.

In July 2011, a jury found McGuffin not guilty of murder but — by a vote of 10-2 — guilty of first-degree manslaughter. He was sent to Snake River Correctional Institution, in eastern Oregon, a notorious facility for violent inmates. He cooked in a prison kitchen and worked on a fire-fighting crew, cutting fire breaks in 16-hour shifts for $6 a day.

In 2014, Janis Puracal, an Oregon attorney who was starting a branch of the Innocence Project, learned about McGuffin and agreed to represent him. She looked at the time window in which he was said to have murdered Leah and disposed of her body. “It just didn’t make sense,” she says. Walter’s role, she surmised, had been to invent for police and prosecutors a compelling narrative to make up for a lack of evidence. “They don’t have a story for Nick,” she says. “Walter comes in with ‘the story.’”

Puracal hired a DNA expert to reexamine the state crime lab’s report. The expert discovered that analysts had found male DNA on Leah’s sneaker that did not belong to McGuffin. The information had never been shared with the defense. “I was over the moon,” Puracal said. “And then I was pissed.” She found more exculpatory evidence: an eyewitness withdrawing cash from a bank who bolstered McGuffin’s alibi but whose account (along with a time-stamped ATM receipt) the state had failed to disclose. In November 2019, a circuit-court judge vacated his conviction and ordered a new trial. Frasier moved to dismiss the charges instead. A few hours later, McGuffin walked into the prison kitchen and told his supervisor that he wouldn’t make his next shift.

ABC aired a follow-up 20/20 episode celebrating McGuffin’s release and examining all the missteps in the case — except its own. When I called Avila, who is now retired, he defended the original report’s accuracy but said he deplored the true-crime genre as “one of the lowest forms of journalism.”

“My friend, 35 years in network television has destroyed my idealism,” he added. “We should all be working for ProPublica. But we’re not. Does that make us bad people? I couldn’t get a job at Frontline. I tried! I couldn’t get a job at 60 Minutes.” Avila said the background sheet his producers prepared had no red flags about Walter. Perhaps no one thought to look him up on Wikipedia as they prepared to air the episode that fall. If they had, they would have seen several paragraphs under the heading “The Drake Case.”

McGuffin is now suing Walter, the Vidocq Society, and Oregon law enforcement, alleging that the state fabricated evidence, coerced witnesses, and withheld exculpatory information. This past June, Walter connected to a Zoom deposition from a Comfort Inn in Scranton, looking tired. He was recovering from cancer and surgery. One of McGuffin’s attorneys, Andrew Lauersdorf, grilled the profiler about his claim that he worked on cases with Scotland Yard. Walter could not recall the name of any inspectors he’d worked with there and appeared not to know that Scotland Yard and the Metropolitan Police are, in fact, the same organization. When asked where Scotland Yard was located, the man who claimed to have visited the agency’s offices up to 30 times said he didn’t know and then offered “downtown London.”

For much of the deposition, Walter spat venom at his oldest friends and allies. He resigned from the Vidocq Society in 2015, saying he no longer trusted certain members. He had quit the board of Parents of Murdered Children because, he said, someone there was embezzling money. (Bev Warnock, the current executive director, says, “I can tell you that is a false allegation.”) Michael Capuzzo was “not the most brilliant chronicler I’ve ever met.” Colleagues at the AAFS were “shallow, quite frankly.” Eight hours of testimony revealed an increasingly isolated man.

A few months after the deposition, I met McGuffin in Puracal’s conference room in Portland. He was still powerfully built from a decade at the weight pile, but his short hair was flecked with gray. COVID brought another lockdown soon after his release; then his mother was diagnosed with cancer and his father died. McGuffin had gotten a job as a chef at a golf course, earning less than before his arrest. He’d received death threats against himself and his daughter. “My life,” he said, “is like a puzzle with the wrong pieces.”

For two hours, McGuffin was composed. Then I asked if I could read from Walter’s deposition, in which the profiler struggled to recall McGuffin. He’d finally given up and said, “Whatever his name is.”

McGuffin’s cheeks flushed. “Wow,” he said. “It’s like I’m a nobody.” His face contorted hideously. His body began to tremble, and he excused himself from the room.

McGuffin had imagined all the ways Walter plotted to ruin his life. He’d thought about it while hacking through the Oregon forest with 80 pounds of gear, while slicing onions in a prison kitchen, and while driving through the night after his shift at the golf course to see his teenage daughter. He’d entertained every permutation but the most devastating: that Walter didn’t think about him at all.

There was another man whom Walter could not recall during his deposition. “The — I forgot his name,” Walter said. “But anyway, the bad guy.”

Today, the bad guy, Robie Drake, 58, lives in a trailer park in Dutchess County with Marlene. A court tossed out Drake’s second conviction because of “irrelevant and prejudicial” bite-mark evidence. In 2014, facing a third trial, Drake pleaded to reduced charges and was released. After my emails and calls went unanswered, I staked out Drake’s home in the fall, and he finally appeared in an old pickup. “It’s been hard,” he said, when I asked about life after prison. His eyes were wide and wary. He promised to consider a formal interview, but never spoke to me again.

The Vidocq Society still meets regularly, its promise so alluring that even old marks are back for more. In October, prosecutors from Ocean County, New Jersey, traveled to Philadelphia to present a cold case. This is the same office that had deemed the Vidocq Society’s investigation into Zoia Assur’s death “preposterous.”

Walter is still active. In October, he spoke at the North Carolina Homicide Investigators conference. As recently as 2019, he was available for work as a profiler. That year, Joey Laughlin, the sheriff of Fayette County, Indiana, was reinvestigating the 1986 disappearance of Denise Pflum and hired Walter for $3,000. “If I were the perp,” Walter told a newspaper after arriving in the state, “I wouldn’t buy any green bananas.”

Laughlin had two main suspects, and he played interrogation tapes for Walter. Shortly after the second one began, Laughlin’s chief deputy nudged him: Walter was dozing off. When he woke up, he was sure the suspect from the first tape was the murderer.

Pflum’s parents were thrilled with Walter’s involvement and didn’t mind the napping episode. “Old people tend to nod off,” David Pflum says. He wasn’t aware that Walter had recently called Laughlin with a new theory about Denise’s killer.

“I’ve been thinking,” Walter said. “I think it’s the dad.” He mentioned that to do any more profiling work, he’d need another fee.

“I think we’re good,” Laughlin said.

Denise Pflum’s disappearance remains the great mystery of the town. “Maybe I’m more cynical now,” Laughlin told me. “There’s not this great person who’s waiting in the wings to come save the day.”

In December, I drove to Walter’s large, well-kept six-bedroom house in Montrose, Pennsylvania. An aging Mercury Grand Marquis sat in the garage, and on his front porch, an American flag was draped across a deck chair. There was no answer when I knocked. I dialed his landline. “I don’t trust you, I don’t like you, and I will never cooperate with you,” he said from inside the house. “You’re wasting your time.”

I had wondered why Walter hadn’t pursued the anonymity of a city, but Montrose has many appeals. Walter is beloved here. He’s known for his homemade gingersnap cookies, and the bartender at the County Seat, a dive across from the courthouse, relishes hearing about his true-crime escapades. On a barstool in Montrose, he can fully inhabit the character he created without fear of fact check.

The next morning, as a blizzard descended, I made another attempt at his house, ringing the bell and banging on the door. At that very moment, a few hundred miles away in Philadelphia, Walter’s attorneys were filing a new motion in the McGuffin suit. They wanted to quash Janis Puracal’s request for internal documents from the American Academy of Forensic Sciences. As a support, they cited memos written by Paul Frasier, the prosecutor in the Leah Freeman case, saying he had not relied on Walter’s theories after learning about the Drake case and realizing he couldn’t be trusted.

It was a stunning turn. Richard Walter’s best legal defense required finally acknowledging the obvious: that anyone with an internet connection should know he is a fraud.