This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Chapter 1

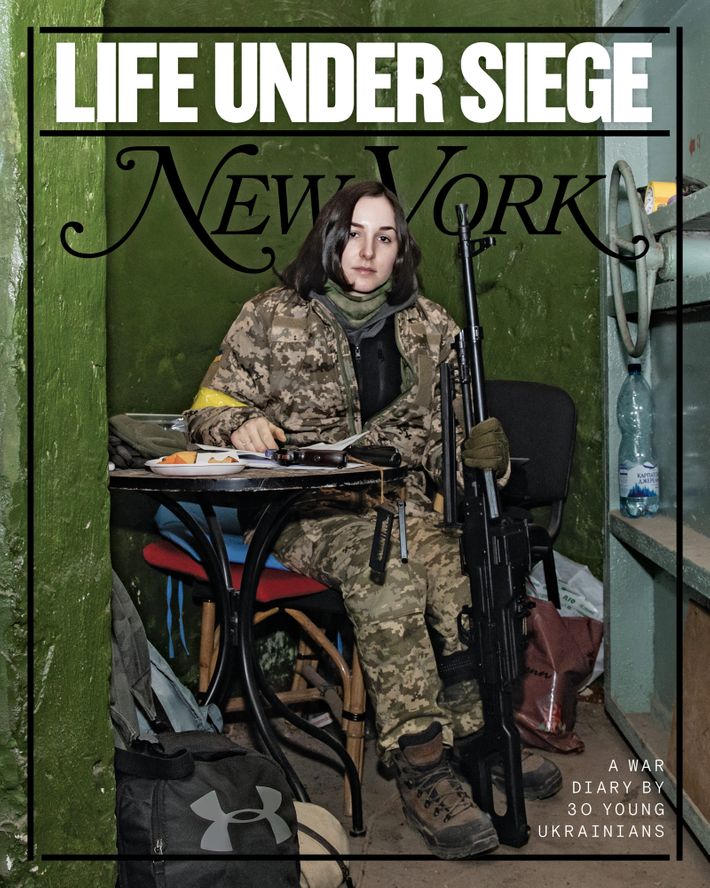

‘I Bought Four Bottles of Wine in Case We Need to Prepare Molotov Cocktails’

February 23

Russian forces surround Ukraine on three sides. The U.S. warns that an invasion is imminent. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy declares a state of emergency.

.

Aleksey, 26, a printing manager in Kyiv

I was standing with my friend on the Yurkovytsia Mountain, which overlooks the whole city, and we joked, “Just imagine — bombs are going to fall on Kyiv.”

.

Viktoriia Khutorna, 24, a television journalist in Kyiv

In the middle of the day, I texted my English teacher. We were supposed to meet, and she said, “I’m sorry. I totally forgot about our lesson.” She had decided to leave Ukraine at the last minute and was on her way to the airport. I said, “Why didn’t you tell me before? I might have planned something else.” So now I had a free evening and nothing to do with it.

I try to stay out of politics. Ever since 2014, when I was worried about my mom, who protested in Maidan Square, I decided not to be involved or to constantly watch the news because it was traumatizing to follow the news and not know what’s happening to my relatives.

Later, I was on the phone with my mother and told her I had a bad feeling. She said, “Don’t worry. It’s crazy to invade Ukraine fully — especially Kyiv.”

I said maybe I should leave for a couple of days. But then I thought, I don’t really have money. So I spent some time watching Inventing Anna on Netflix and learning some English by myself.

.

Petro Chekal, 20, a student in Kharkiv

On the TV at 5 a.m., Putin announced the beginning of the military operation, just — war. Here is Mitya, my brother, listening. This is a Russian TV channel, and they said it was a rescue mission. My grandparents watch Russian TV all the time, and for the first few days, they couldn’t believe it. And when they finally did believe it, they switched to Ukrainian TV.

.

Leonid, 19, and Nasta, 21, siblings and sociology students in Kyiv

Leonid: I was anticipating a new video game that was supposed to be released the following day. But I had been sensing that something was going to happen. Two or three weeks prior, there were Russian troops building up along the border and people had started to prepare for the worst. I rarely remember my dreams, but one of those nights, I woke up and told Nasta that I dreamt the war had started.

Nasta: It had such a profound effect on me that I did not sleep for the next two hours, although Leonid fell back asleep almost instantly. But on the 23rd, we both thought we’d have at least two or three more days to prepare.

.

Daria Holovatenko, 18, a university student in Avdiivka

That day, I was hanging out with a friend at my parents’ café, talking about going to America as part of a work program for students. I really want to visit Los Angeles, maybe work as a hotel receptionist to improve my language skills and learn about the culture. I also got a message from my professor, who suggested I take part in a Chinese-language competition whose winner would go to China. I was so happy to have been chosen.

We saw on the news that Ukraine was declaring a state of emergency and the American warning. Even so, I didn’t think the war was going to happen. None of us believed an invasion was imminent.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi, 26, a poet and journalist in Lviv

My partner, Yulya, and I watched President Zelenskyy make his speech to the Russians that night. I liked it a lot — clear, focused. I thought Putin was bluffing because an invasion seemed stupid. Extremely stupid.

.

Mariia Shuvalova, 28, a Ph.D. candidate in Kyiv

Very late at night, I got an alert that probably Russia would invade. I was shocked, and I started charging my laptop and power bank but then I thought, No, that is impossible. It’s dumb. It’s just crazy shit. And I went to sleep.

February 24

Just before dawn, Russian bombs strike Kyiv, Odesa, Mariupol, and Kharkiv. Tens of thousands of troops cross the border.

.

Inna Zadorozhna, 25, out of work in Cherkasy

My phone started exploding with notifications. My friends were writing “Watch! Watch!” with YouTube links. The Russian president was on live. I was sleepy; I didn’t realize what was happening. Why was he speaking live? All normal people are asleep at this time.

Around 5 a.m., I started receiving notifications about explosions in the biggest towns and cities. I was still thinking that this is some joke, that this is not real. I didn’t know what to do. I waited a little bit, 30 minutes, and got afraid and went to wake my mother. She was really angry: “What do you want?!” And I told her, “I think war started.” She asked me, “War? Which war?” And I said, “Russia invaded Ukraine.”

.

Victor Dobrovolskyi, 21, a drama student in Kyiv

A friend called me at 5:35 a.m. I wasn’t surprised it was so early — he often gets into trouble. I said, “What happened to you? What do you need help with?” He said, “You haven’t heard that the rockets are flying near Kyiv?” I asked him what the fuck he was talking about.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

It was a fucking mess. There was shock, utter shock. For an hour, I just sat there reading, not knowing what to do. My hands shook. I didn’t wake anyone. My partner was lying next to me, but I didn’t say anything; in the next room, my mother was getting up to go to work, and I didn’t say anything.

Finally, I told Yulya that the war had started. She didn’t quite understand at first because, really, the war had been going on for eight years in the east — but now there’s a full-scale invasion. And it feels like total annihilation because they’re shooting at civilians.

.

Anastasia Kovalchuk, 19, a university student in Kyiv

When we heard the first siren, we went with our things to a bomb shelter. It was very cold. There was no cell service and no internet, so despite the shots that we heard, we had to go outside to get the news and ask others if everything was all right. We spent seven hours in the bunker, and as soon as it was quiet, we went home to eat and shower. When we heard the sirens again, we went back.

.

Inna Zadorozhna

The first thing my father did was to go to the gas station and fill the car, and my mother went to the pharmacy. The lines for both seemed kilometers long. Cherkasy is not big, not even 300,000 people; I have never seen traffic jams here, but that morning it was almost impossible to leave by car.

Later, we were sitting in our house and planning where to go. We live almost in the center of town, and that’s dangerous now. We had the idea to run to a smaller village nearby, but then my mother, who works as a security guard at a kindergarten, received a phone call and was told she was needed. We decided to stay in our home. It’s dangerous to leave it empty because somebody could enter and steal everything.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

We were really worried because we live near one of Kyiv’s major airports and our flat has massive windows. We packed for five minutes. We took laptops, documents, and some random stuff that was on the table. I took fancy underwear, some books — one called Stop Being a Nice Girl and Stephen King’s On Writing. Also a fancy dressing gown. It’s silky. It can serve you pretty well as a bandage if someone breaks a leg.

My university sent a message suspending all lectures. A few hours later, I heard that one of my students has already volunteered to go to the army. He’s younger than me. Nineteen.

.

Julia Berdiyarova, 28, a museum worker in Kyiv and Odesa

This morning in Odesa, there was a lot of sun. It felt like spring, and I woke up in a good mood. Then I took out my phone and saw that Russians had invaded my country. I had a lot of work planned, and I called my colleagues to ask, “Do we cancel our meetings today?” This was a little bit absurd because everything was canceled. All your life is canceled.

My primary job is in Kyiv, but I had come to Odesa before the invasion — I’m trying not to call it the “beginning of the war” since the beginning of the war was eight years ago — because of the stress and because this is my native city. I didn’t bring much: clothes, documents, all my money. I was sure I’d be here only for a week and after that I’d come back to Kyiv again, so a lot of things that I need I left behind. And I feel sad because little things like sculptures or books, these poems that I want to read now, stayed there. But my mother told me, “You took yourself, and this is the most important thing you take.”

.

Victor Dobrovolskyi

I sat at the computer all day watching the news. I was filled with hatred every time I read about the Russians, but I was even more outraged that the Russians were openly lying that they were only hitting military facilities, that they came with peace, that they came to save us. From whom?! From ourselves?

.

Aleksey

I smoked three packs of cigarettes. When my mind was clear, I decided that staying in a big city during the war would be a big mistake. I started calling all my close people in Kyiv and begged them to leave immediately, but no one listened to me except for four friends. We met at the station — it was still relatively quiet — and decided to take the first train to the west. We boarded without tickets and without paying. The atmosphere was gloomy. But we got to the town of Kovel, in the northwest of Ukraine, where we had heard there was no fighting.

.

Leonid and Nasta

Nasta: Like many of our friends, we had an opportunity to leave for Lviv, near the Polish border, but we didn’t give it much thought. We are going to stay in Kyiv and fight for it if we have to.

Leonid: I saw a warplane for the first time in my life on the way to the supermarket. The shelves were quite bare, but I bought four bottles of wine in case we need to prepare Molotov cocktails.

Nasta: It was the cheapest wine — we just poured it away. Sirens went off five times throughout the day. We live on the top floor of an apartment building, which is very unsafe during air strikes, but nearby we have a spacious parking garage as a shelter with power outlets and restrooms and okay internet. We can bring our cat. There’s also an area where people can just sit and talk, eat, drink tea. I’ve never had as many friendly conversations with my neighbors as I do in the shelter.

.

Victoria Vlasenko, 23, a customer-support manager in Kyiv

I tried to work a little, but it was hard. Our company’s chat was full of messages about people hearing bombs and explosions. I was thinking about whether I had to leave, but I have two cats and it’s difficult to travel with them.

We went out and saw the longest queue to the supermarket I’ve ever seen. I didn’t join. We thought this thing would end quickly and that everything would be fine, that it was just politics.

.

Julia Berdiyarova

I also work with a museum here in Odesa, and my colleagues asked for my help taking all the works off the walls and getting them to a safe place. My favorite works are from the avant-garde period. A group of young artists born in Odesa went to Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, and at the start of the Soviet era, they came back and formed this group called Odesa Independent. I told everybody at the museum, “With Odesa Independent, don’t help me; I’ll take it myself. Because these are my guys.” One of these paintings is a landscape made in a Cubist style by an artist named Amshey Nurenberg. It shows human bodies washing in the river, and there are a lot of open colors: blue, green, ocher.

These works have a really interesting story. During the Second World War, they were evacuated from the museum. Now they are in a safe place in another wartime.

.

Daria Holovatenko

There was heavy shelling here in Avdiivka, which is maybe two hours by car from the Russian border, so we went to the nearby school where my mother teaches and sheltered in the basement before taking off again. We headed for Dnipro, but then we opted for a smaller town nearby, Novomoskovsk. The journey was scary because we didn’t know if we would see Russian soldiers. By this point, though, I felt numb. I had cried a lot in the morning: There had been so much fighting around our town in 2014, and I just didn’t want to experience war again — the death, the destruction, the fear.

.

Anastasiia Viekua, 27, a Pilates instructor in Kyiv

My husband has a 15-year-old son, so we bought him a ticket for a train that would leave in the evening for Lviv, where my parents live. And we managed to buy tickets for ourselves for the next evening.

But with every hour, sounds of attacks were closer and closer, so I insisted that we try to get on the first train with my stepson. We packed what we could take. I was crying the whole time because I am someone who buys only the stuff I really like — I couldn’t choose what I should and shouldn’t take. I packed some jewelry from my mother and grandmother and clothes that will be warm because it’s minus-two degrees Celsius and snowing in Lviv. I took gifts from my father and from some people whom I might never meet again. I packed clothes made by Ukrainian designers. I don’t know when I will be able to wear an evening dress, but I wanted to take it with me.

My best friend met us at the train station, so there were four of us but only two tickets. Then a miracle happened: A carriage was booked for another group, but they didn’t show up, so all the people waiting got inside. There were so many animals in the carriage. Some cats ran away from their owners, and people were looking for them throughout the night. Usually the journey takes eight or nine hours, but for us it was 14 hours. Nobody was sleeping. Everybody was awake, checking the news. We were like zombies.

.

Viktoriia Khutorna

We thought we’d leave Kyiv the morning of the 25th — me, my brother, and his fiancée. But late the night before, a friend called and said we should get to a safe place immediately. My brother and his fiancée didn’t want to, but I made them come with me to an underground parking garage with only backpacks, laptops, and some documents. We waited. At 4 a.m., everything seemed fine and we decided to go back to the apartment, but after 20 minutes we felt an explosion, like something was bumped. We expected another bomb, because we thought it might be like in a movie: If there was one bomb, there will be another. We stayed in the parking garage until the morning. We decided we should go to the apartment, grab our stuff, and immediately leave. But for where?

.

Katya Vasiukova, 26, an actress from Kharkiv

The first days were calm, but then several houses were burned down. My friend found a driver, and I had 15 minutes to pack. In Lviv, my friend Anton received me. Different families had settled in his house. It was interesting to watch the children, my own and others. There was a box of military toys in great demand. The children played war and said phrases they heard from the news or their parents, like “The bombs are flying,” “Attack.”

Chapter 2

‘Shelling and Rockets Are Terrible. But Nothing Compares to Air Strikes.’

February 25

Russian forces reach the outskirts of major cities. Kyiv is expected to fall within days. Ukrainians hunt for saboteurs.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

These first few days have been terrifying and disjointed because you can’t understand what the Russians want. Do they want to bomb the whole country or part of the country? We’ve started to pack bug-out bags. We ran to the supermarket to buy groceries that wouldn’t spoil. At the same time, we’re reading the news — everyone is constantly reading the news — just to understand how quickly everything is moving. There have begun to be a lot of civilian casualties.

People are feeling an immense amount of hatred toward Russians. I’ve been to Russia a lot, I have friends there, and I know that there’s an authoritarian regime and that people aren’t always at fault for having a terrible government. But I understand it. You start feeling something different, an unbelievably passionate hatred. I mean, I’m an extremely peaceful person, but I feel downright happy that the Russians are also getting killed.

.

Victor Dobrovolskyi

I woke to the sound of an air-raid siren, and we moved to the bathroom as the safest place in the apartment. A few hours later, my father returned home and we decided to pick up my grandmother and her two cats from the left bank of Kyiv. Now we have eight at home: me, Mom, Dad, Grandma, and four cats.

I tried to join the Territorial Defense, but they said they already have too many people and prefer those who have combat experience.

.

Victoria Vlasenko

I tried to work for a few hours. I was almost the only one because the rest of my team were in bunkers or basements or trying to leave Ukraine.

We have a bunker in the basement of our apartment building if we need one. We gathered with our neighbors to clean it because it didn’t look like a place where people could live; it was absolutely dirty and dusty, and there was no furniture. But I haven’t been in the basement since all this started. I’m a little bit careless about that.

.

Daria Holovatenko

After we got to Novomoskovsk, to the west, Mom made me pancakes with apricot jam, which cheered me up. Then we went to the market to buy more food and look around our new neighborhood. Normally, I don’t eat candy or pastries, but I’ve started eating loads. The war has stopped university classes, but I did some Chinese and English exercises to distract myself.

We were talking about leaving the country, but my dad has to go back to work in Avdiivka and my brother is in Kyiv. Maybe Mom and I could leave, but we don’t know what would happen in another country. We’d have to rent a house, which would be too expensive. So we don’t have the option.

.

Vika Zavhorodnia, 30, an artist and a translator in Kyiv

My friend Ilya invited me to come stay with him, so I packed a few sweaters and underwear. My favorite band is Queen, and I’d painted a huge picture of Freddie Mercury that sits right above my piano, so as I left, I said, “Freddie, please guard my flat!”

But on the way to Ilya’s, he called and said he’d heard about a friend who had managed to get out of Kyiv on a train. I agreed that we should make a run to the station. When we got there, we looked for anything going west and found one heading to Warsaw. It was so crowded — people were shoving — they were desperate, wild, just trying to save their lives. We begged the attendant, and she let us on, handing us bedsheets to sit on in the aisle.

After a few hours, the train stopped and they turned off the lights. We heard shooting and explosions, far away but clear. It was like 1941, like the stories our grandmothers and grandfathers would tell us about that war. Then we started moving again, and the attendant said we could turn the lights on.

.

Anastasiia Viekua

I definitely wasn’t practicing Pilates in the beginning, and when somebody from abroad told me about some new technique, I just sarcastically laughed. Like, Come on, there are bombs here. But I started practicing again. I know how trauma freezes in the body, and I didn’t want this for myself.

.

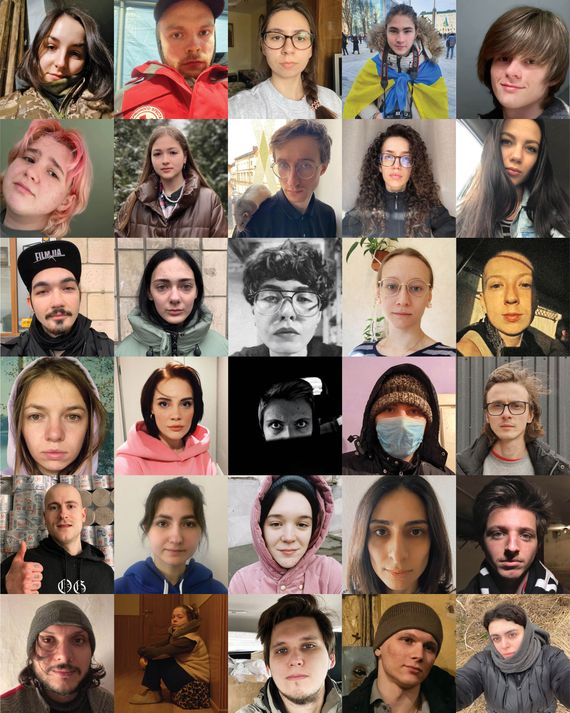

Lisa Bukreyeva, 28, a photographer in Kyiv

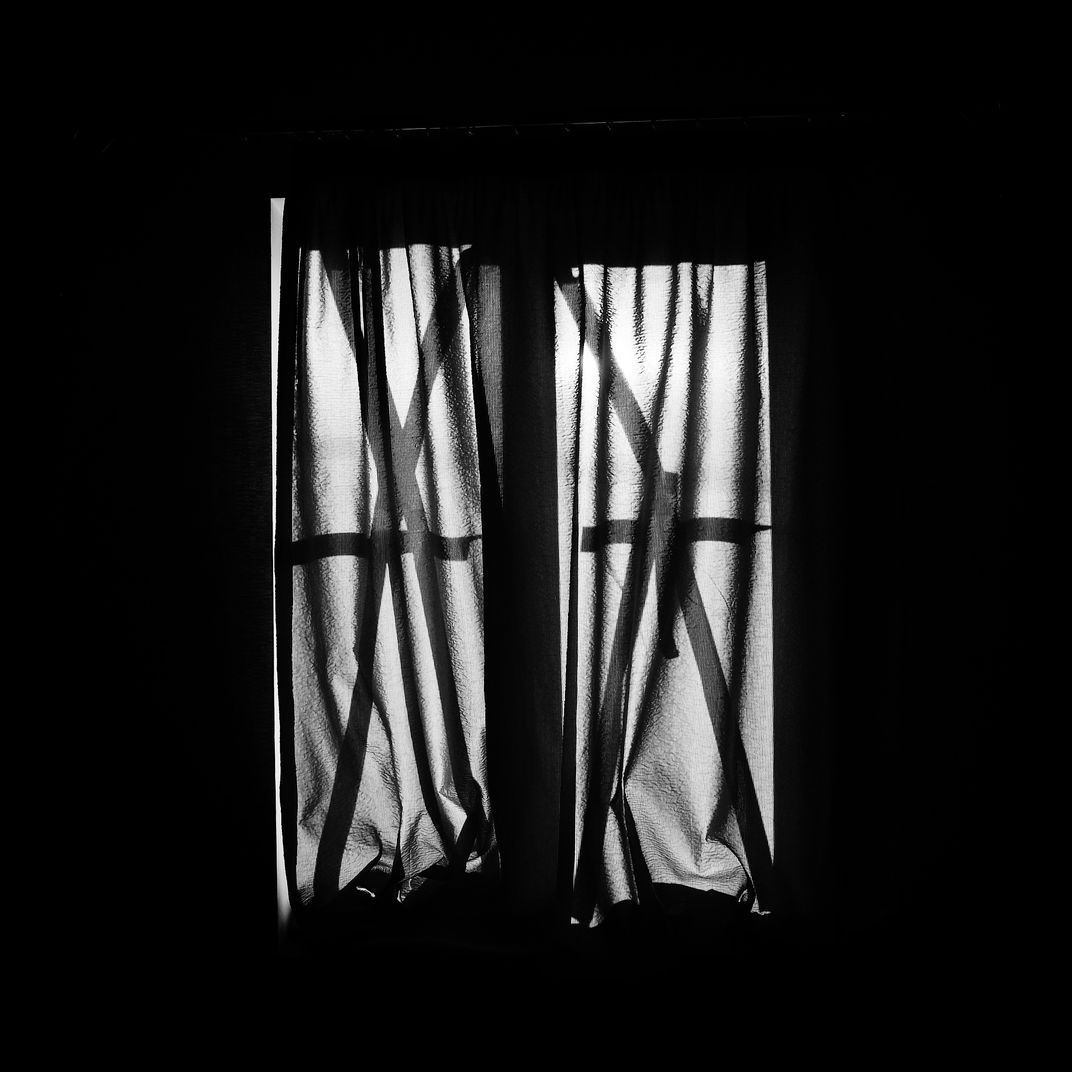

We tape the windows to avoid blast fragments.

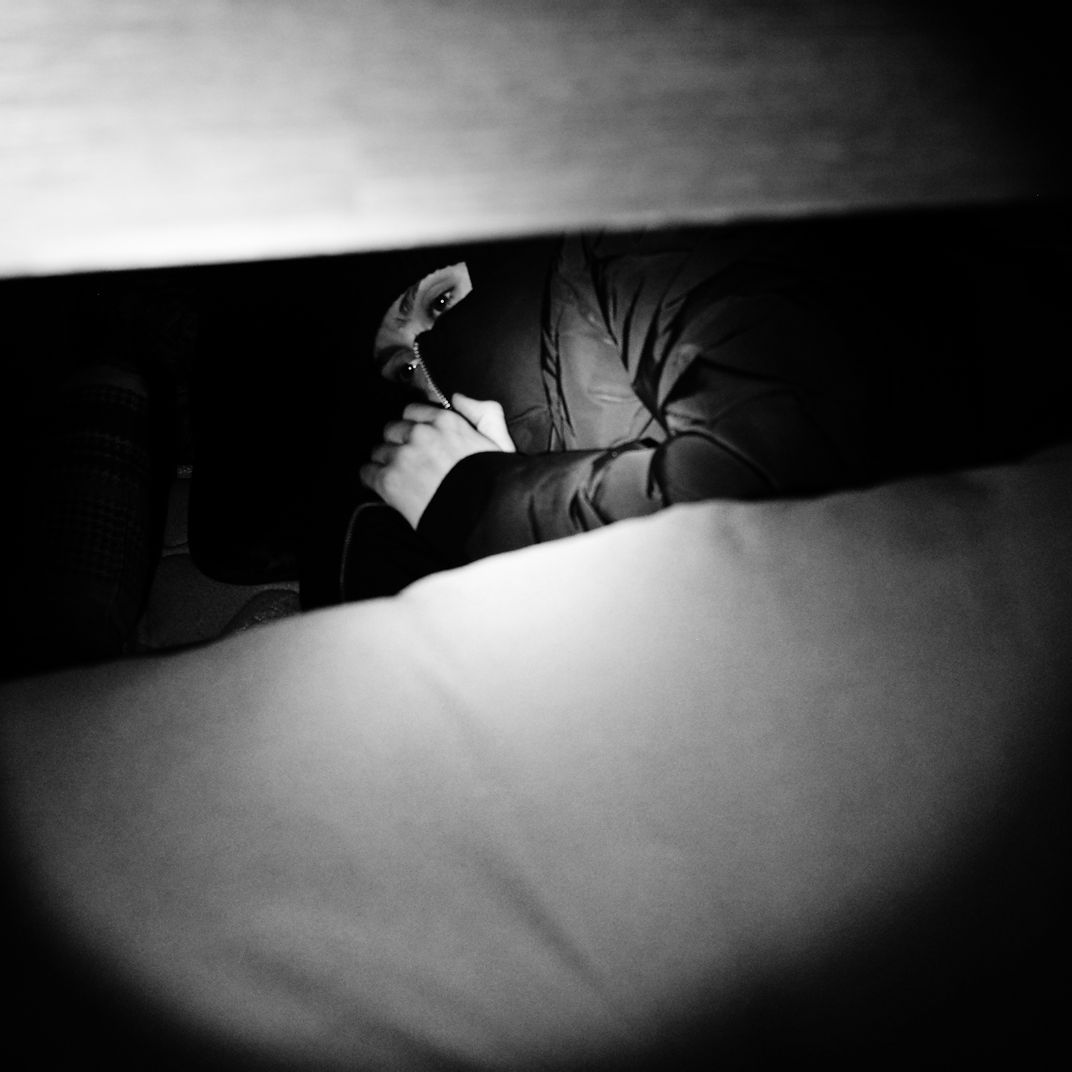

The safest place is the basement because there are rocket attacks at night. We brought mattresses down here and take turns sleeping under the table.

My brother, who is 14, didn’t watch the news in peacetime. Now he watches 24/7.

In case of quick evacuation, we sleep in boots and coats. It feels like I was born in shoes.

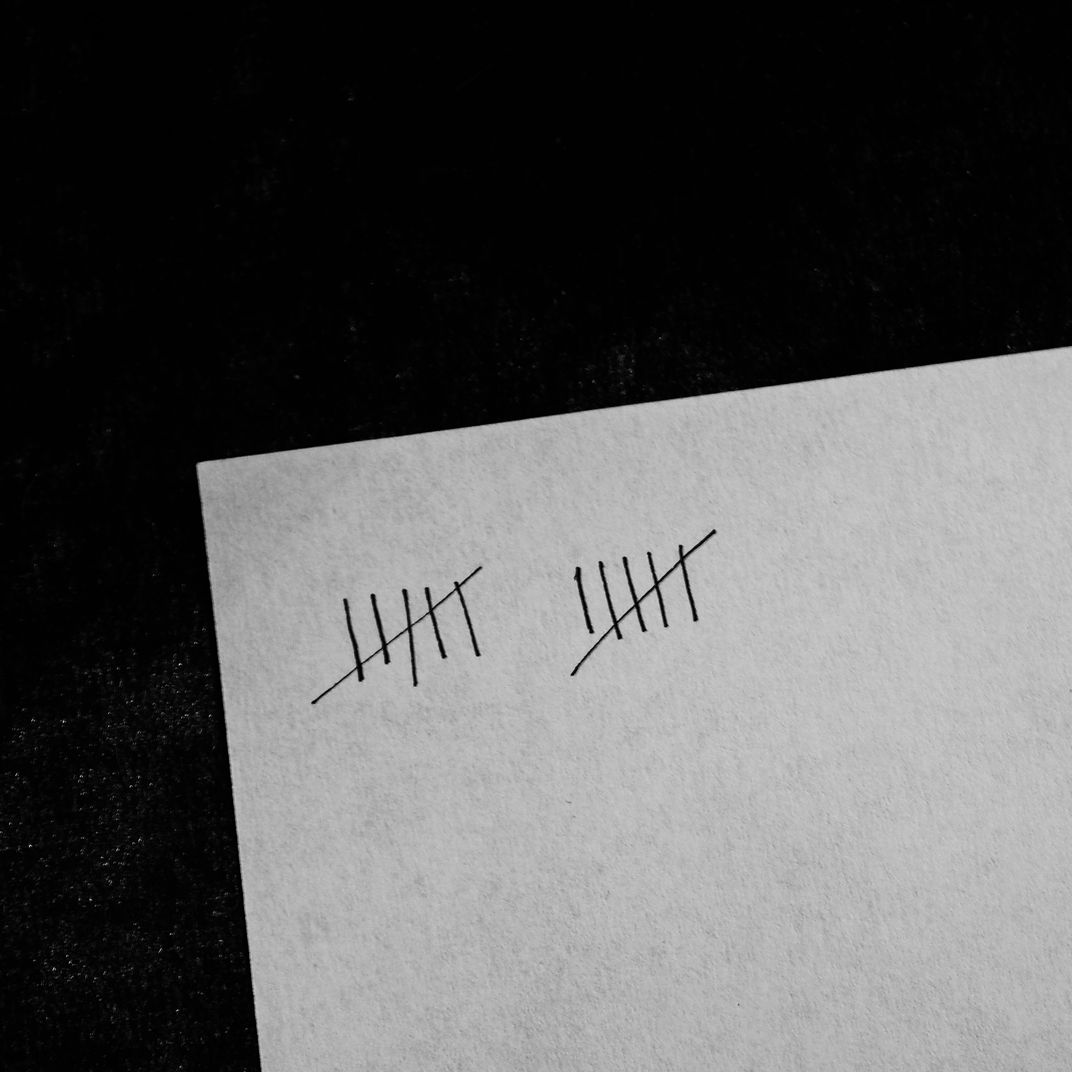

Because of the lack of sleep, it seems like it’s one long day, but the diary helps keep the days separate.

I look at photos of other Ukrainians. We all share a common look — the desire to fight in spite of all the horrors. There’s something disturbing in it.

We tape the windows to avoid blast fragments.

The safest place is the basement because there are rocket attacks at night. We brought mattresses down here and take turns sleeping under the table.

My brother, who is 14, didn’t watch the news in peacetime. Now he watches 24/7.

In case of quick evacuation, we sleep in boots and coats. It feels like I was born in shoes.

Because of the lack of sleep, it seems like it’s one long day, but the diary helps keep the days separate.

I look at photos of other Ukrainians. We all share a common look — the desire to fight in spite of all the horrors. There’s something disturbing in it.

.

Alexander, 26, an engineer in Kharkiv

My employer had offered an evacuation via Lviv, but it was clear to us that it would become a major choke point for refugees. My fiancée and I thought staying would be okay. Tonight, we discovered a McFlurry in the freezer. We thought it was probably the last piece of McDonald’s left in the country. We were pretty happy to find it. It showed us that we had lived in a civilized country once.

.

Viktoriia Khutorna

My brother, his fiancée, and I decided to go to my uncle’s house, 40 kilometers outside Kyiv. We were driving and everything seemed fine, but then we saw soldiers on the road. We didn’t know if they were Ukrainian or Russian. It was so stressful. We were on the phone with my uncle counting down the minutes to his house on Google Maps — “Eight minutes away, six minutes, five minutes …”

When we arrived early in the morning, I hugged my aunt and cried. We hadn’t slept in 24 hours. She gave us some food because the whole night we hadn’t eaten. My niece woke up; she hadn’t seen us for a while and asked, “Who are these people?” We introduced ourselves and said we were going to stay for a while. My aunt asked if I wanted to sleep in a separate bedroom or with my brother and his fiancée. I said I would stay with them. It feels safer in a way, at least for my brain.

February 26

.

Aleksey

“Spy mania” escalated overnight: All the citizens began to see refugees from other regions as Russian saboteurs. Our first day in Kovel, everything was quiet and then this morning, when I went outside, it was a totally different picture: men in uniforms, military vehicles, barricades, sandbags, roadblocks.

I was standing on a bridge, looking at the water, scrolling through the news on my phone, when I heard a rifle bolt click behind my back. I turned around, and the muzzle of an AK-47 was pointed in my face. Two policemen told me from the start, “You are a saboteur. I will shoot you now.” I immediately burst into tears, but not because I wanted to solicit mercy or compassion. It was an emotional reaction to having a gun in my face. They took me to the station and put me through a very thorough interrogation. It was emotional torture — maybe that is too strong a word. Humiliation. They constantly threatened to take my phone and smash it against the wall.

.

Inna Zadorozhna

Today my father expressed his wish to join the army. He has a heart condition and has had several operations on his knee and back, and my mother and I were asking him not to go. He told us he had already visited the place where you sign up. And he left us.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

These first three days, I haven’t been able to eat at all. I’m dizzy all the time. My menstruation has started, and I have diarrhea. But you don’t feel hungry or thirsty — you feel energized. It’s like you’re using drugs.

All night, we are being bombed. We stay outside during the day, but when we hear sirens, we go into our basement. You sleep for 30 minutes and then you come out. We have a phone app about missile attacks, so you know when there are air raids and when the danger is over. Yesterday I wasn’t able to sleep because I was afraid I wouldn’t hear my alarm and wouldn’t run to the shelter and I would die.

February 27

Fierce and surprisingly effective Ukrainian resistance slows Russia’s advances on Kyiv.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

At the train station in Lviv, huge crowds of people are trying to cross the border. There are confrontations — some guy with a knife grabbed a teenager, saying, “Why aren’t you defending your homeland? Why aren’t you letting women and children leave instead of trying to flee?” There are instances of racism, when they won’t let on people with darker skin, and there are other occasions when people with darker skin will let only their own people on. Basically, though, there’s an overall feeling of solidarity because everyone around is trying to help everyone else.

.

Inna Zadorozhna

It’s forbidden for my father to call from his military unit and tell us his location. But he did call us and tell us to get to a shelter because there was a high risk of bombing.

The sirens go off every day, constantly. People really get angry. You get the notification to hide — it might last for hours — and then you get the notification that everything is okay and you can come out and then, ten minutes later, you hear again this terrible sound. Our mayor wrote us a message: Please, people, don’t be angry because of that. Every time you hear a siren and hide but there is no sound of an explosion — this is the work of our army that protected us.

Our shelter is beneath the house, a place where we usually kept vegetables. It was built a long time ago by my grandmother and her grandfather; they hid there during the Second World War. It’s very cold. The first time I went, I wore two sweaters and a winter jacket and still was trembling. After we got out of there, I covered myself, I drank a hot tea, but even so it took me around a day to recover from the cold. Now I use more layers.

The worst thing that can happen to Ukraine is to be under Russian government. I’m sure they would destroy Ukraine’s culture, our language — what makes us Ukrainians. As a good example, Crimea: I have an aunt there. We had a good relationship. But when Crimea got occupied, they started having only Russian news, and at one point she called us and said, “I hate Ukraine. I hate Ukrainians. You are not normal there, you eat Russian-speaking babies. I don’t want to know you. Please don’t call me anymore.” That was from my aunt, who knows us.

.

Aleksey

After being arrested on the bridge, I was afraid to stay in Kovel. My friend and his girlfriend and I decided to go to Lutsk, where my friend had been given an apartment by his relatives. But here’s the thing: They told him, “It’s only for you and your girlfriend” — not me. I said, “I hope this is a joke,” and his answer was, “Understand, it’s war now; every man for himself.” I was shocked. I considered him my younger brother. I raised him, practically. I think a person’s true character reveals itself in difficult situations. It’s good that now I know who I can rely on.

We agreed that I could stay with them for one night in Lutsk. After we arrived, I went to the train station to check the departure schedule, and five men with Kalashnikovs surrounded me. They were agitated, but compared to the men in Kovel, they were pussycats. They checked my documents, stripped me to my underwear, and asked me to explain my tattoos. They took away my phone and searched through every single record. The freaks looked at my sex videos. It was fucked up, but what can you say to people with guns during martial law?

They took me back to the apartment where I was staying with my “friend.” It was sort of funny — me casually going to the train station and coming back in the company of three armed men. My friend and his girlfriend did not talk to me afterward.

.

Roman Vydro, 27, an engineer and entrepreneur in Kharkiv

I co-founded a community workshop where people can fabricate projects with machines. I used to think our windowless basement was a disadvantage. Now I realize how lucky we were. We called it a “luxury shelter” with a kitchen, bathroom, shower, and places to sleep. We’d have 30 to 60 people throughout the day.

Early on, a young woman named Anna showed up. I had never met her before. She said she was just visiting Kharkiv when the war started; her backpack was only big enough for a weekend trip. Things were getting worse, and my colleagues and I decided to drive west to safety. She had to trust us strangers. We squeezed her among 12 people and four animals — a dog, two cats, and a turtle — in two vehicles and drove for the last three days to Chernivtsi, checking which cities were not under fire and which bridges still existed.

We passed car crashes, wondering whether the people in them were alive or dead or injured. Perhaps we could help them? But by the time these thoughts landed in my head, we had already left them behind. Those thoughts still haunt me. We crossed the bridge over the Dnipro River, hoping it would not explode with us on it.

.

Markiian Matsiiovskyi, 28, a DJ and film director in Kyiv

I moved in with friends and made a post on Instagram to collect donations to buy supplies for the Territorial Defense. Food, energy drinks, cigarettes — the last made them particularly happy. One time, I was in the checkout line when the siren went off, and I did not care because I had to buy food that people needed.

I’m a workaholic by nature, and knowing that what I do is needed by others brings me comfort. I don’t earn any money from this. We don’t speak in terms of weekdays and weekends. When we started our work, we understood there couldn’t be any days off. I named our group

An Object Under Angels’ Protection, and I want to think we are, in a way, angels.

We have two headquarters, one on the right bank of the river, the other on the left. In the evening, we do inventory, compare it to the list of requests for help we’ve received from a group we created on Telegram, and determine what we have to purchase. We help hospitals, especially children’s ICUs, that are the most vulnerable; young mothers who aren’t able to leave their children to wait in line at stores; and the elderly. Medicine remains a problem, and we have to order it from the west. When grannies in our building find out we are volunteers, they knock asking for food and medicine.

My friends and I made an agreement that we won’t talk about the war, only fantasize about what we would do when it is over: One friend plans to visit Portugal, another Japan.

.

Markiian Matsiiovskyi

At first, we were delivering by taxi, but soon we got more volunteers and some had cars. We have 50 volunteers in Kyiv now. In the beginning, the majority were young people, but now older people also realize that they shouldn’t sit and wait it out, that they should do something to be helpful.

.

Anastasiia Viekua

We spoke to my relatives who live in Russia, and they literally don’t believe us that there’s a war, despite the fact that we had to leave our homes. They told us Putin will help us and will save us and then they said “Burn in a fire” and hung up.

.

Inna Zadorozhna

For days, I was crying, crying, crying, crying. I have these wounds under my eyes because in the shelter I touched them with dirty hands and it got red. I’m trying to keep my sense of humor and a positive mind to resist depression. But I don’t listen to music because I don’t feel safe — I worry about not hearing sirens. I look at pictures of cats on Reddit with everything silenced so I’m not distracted from the sounds outside.

Before, I was ambitious. I had a lot of dreams. I finished nursing school, and right after that I entered university. I wanted to be a teacher of English, German, and foreign literature. I was thinking about which job to choose, about what to buy. Now, I’ve realized the only thing that matters is peace. To wake up and feel safe.

.

Alexander

My fiancée and I started setting our alarm clocks to go off every two hours during the night so we could check the news. But within a few nights, the shelling had gotten so bad that alarms were pointless. We could hear the bombing with our own ears.

We used to live in Donetsk, so we have experienced shelling and rockets — and those are absolutely terrible — but nothing compares to air strikes. With air strikes, there is no safe place. By the time you hear the plane, it’s already too late.

.

Victoria Vlasenko

Actually, our lives haven’t changed much. We went to the supermarket in the morning because it had been two days and we needed water. There was a big queue, and after that we went back home and stayed in all day working, sometimes watching news, sometimes watching just TV shows.

The atmosphere here is, for me, a little bit aggressive with the word victory. I hear that we are fighting, that we are killing all the Russians and we are going to get this victory, that either we win or the Russians lose. So it’s very patriotic and nationalistic. The politics of our country have been like this for the past ten years, but now it is more extreme. We are spreading as much propaganda as the Russians.

.

Yasia Myroshnychenko, 18, a student in Kyiv

My family spent the first days in a bomb shelter. My little brother is only 5. He asked my parents and me, “Why can I not sleep in my bed?” He heard the explosions, so we couldn’t hide the truth from him. Once the attacks subsided, we got out of the shelter and drove all the way to my grandparents’ house in the western part of the country. When we arrived, we organized another shelter with food, water, blankets. We noticed that my brother couldn’t enter any room alone — he thought there would be Russian soldiers or explosions or fire. After more time in the bomb shelter, my brother and all of us started to get sick. It was unbearable. This was the time we realized it was time to flee Ukraine. We drove with my father to the border of Romania, then I just got out of the car with my mom and brother and crossed the border on foot.

February 28

.

Mariia Shuvalova

Our parents do not know how to use smartphones, and they are unable to fight so they are feeling helpless; a lot of people here are feeling guilty. It’s another challenge to deal with the psychological moods of all the people around here because everyone is perceiving the war in a different way. My friends, some brilliant academics, are just speechless, unable to do anything despite having resources, but I’m like a crazy maniac, able to talk 24/7.

I don’t wash my hair. I don’t brush my teeth. You feel like you don’t need that — there is important stuff to do. I have COVID right now. I am fully vaccinated, but still it got me. It’s a distraction. Despite everything, our spirit is pretty high because we are winning.

My husband is doing worse than me because he is a man and he feels that he has to take a weapon. But he doesn’t have military experience, he doesn’t know how to use weapons. We are a feminist family, and I try to remind him that despite the fact that society may pressure him, I have the same need to take a weapon as he does.

We have two small kids here, 4-year-old girls, along with their parents and cat. The girls know that bad guys came and now we have to hide. It’s like a game for them.

March 1

Russia steps up attacks on cities, striking the heart of Kharkiv with missiles.

.

Aleksey

I found a driver to take me to Lviv through BlaBlaCar, an intercity ride-share service. There were checkpoints every 20 kilometers, but we passed without problems because everyone knew this driver and he introduced me as a member of the National Guard. Ha!

In Lviv, I was sheltered by someone I had never met — a fellow member of an all-Ukrainian bicycling chat room. He turned out to be a saint. He offered me everything I needed; I was safe and in complete comfort. It’s amazing how total strangers are willing to help one another.

Monday was just a tranquil, worry-free day, maybe for the first time since I left Kyiv. Lviv is now just a Disneyland for refugees, free from both Russian aggression and Ukrainian paranoia. It’s almost too comfortable.

.

Anastasiia Viekua

I went to the store in Lviv, and there was no porridge or canned food or sausage. I’ve been eating simple food, but if I can find the products, I’d like to cook chili con carne for my family. Yesterday, I was speaking with my friend and we decided to have a routine in the evening where we share our successes. Her success was that after hunting for three days, she finally got three kilograms of chicken meat.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

We have a group chat with old people who are living in our apartment building in Kyiv. It’s 25 floors, and we were sharing information: where is the shelter, where is the electricity, where is the water. Today, we realized a Russian guy was in the chat. He started texting that we will die, that we are terrible people, that he knows the location of this bomb shelter.

We are closer and closer to that point that we don’t care, that we just won’t run to the basement. I hardly remember my life before the war. There is so much going on that you are unable to process it. Each day of war is like a year of your life, and your body reacts to everything differently.

We had a chance to leave Ukraine. My husband’s company — he works for an international IT company — suggested everything for us: transfer, money, a new home. And people are reaching out to me, offering to pay for a new home in Canada, Norway, and so on. My husband really wanted me to leave Ukraine, along with our mothers, but I said, “I won’t do that.” It’s psychologically easier to stay here because if you lose your life, you will rest in peace. But if you leave and you lose your family — how could you live with that?

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

I think things are going to be more or less okay in Lviv, unless — well, nobody really knows, but for the time being, we aren’t being bombed. We have sirens now, sometimes once, sometimes four times a day, but there’s a sense that you’re hearing it all the time. You keep thinking you hear it. You go to the window, but there’s no siren. It’s constantly ringing in your ears in the background, and you start thinking it’ll start at any moment. If at first that was really scary, then you start getting used to it.

At first, it was difficult to sleep, and now it’s a lot easier. You go to sleep, you wake up, have breakfast, find out where people need help. You can go to the train station and help unload supplies; you can go to the humanitarian center and sort clothes. They stopped accepting donations of children’s things, because they had enough. They said, “We need menstrual pads. Antiseptic. That’s what we need you to buy.”

The churches are cool. On one side, next to these tiny memorials to people who have died over the past eight years, people are praying, and on the other side, there are huge piles of boxes with donations.

.

Julia Berdiyarova

I got a Google Calendar notification about a work meeting with my colleagues from Kyiv. I took a screenshot and sent it to our group chat and said, “So, let’s call?” It was a joke, of course, but I told them not to delete this meeting because I want to know every week how they are doing. I told them it was a reminder of a normal life.

Every day is like one long day, and I don’t remember when it’s Friday or Saturday or Sunday. My mother has been helping other volunteers, and she comes home quite tired. She works from six or seven in the morning till the curfew. We plan our day before the curfew because you can’t just go out and walk the streets because you may be taken for a saboteur. So we just stay home, not moving, because we understand that this is the most helpful thing we can do for our soldiers, to do everything by the rules.

.

Alexander

My fiancée, Kate, and I decided to go out early to the stores in Kharkiv before the queues, and we split up to increase our chances of getting something. On the way, I met an elderly couple who were pretty depressed, and I tried to cheer them up by saying things were going to get better. At that moment, I felt this supersonic roar. Every ounce of my blood chilled. I dropped to the ground and covered my head. I called Kate and told her to go home immediately.

Then I heard the sirens and looked for cover, but there was nothing, just an open road. I spotted a construction site with a ditch alongside it. I jumped in without thinking and got as low as possible. I was concerned that people would think I was a Russian saboteur planting a bomb. It was ridiculous — my mind was a complete disaster zone.

So I got out of the ditch, covered in mud, and I ran to an apartment block and hid under a staircase. I bumped into an old woman and offered to escort her home, even though every thought in my head was telling me to escape.

.

Petro Chekal

After the invasion, it was impossible to stay in a house with the windows taped shut and to hear explosions getting closer and closer — any more of this and you’ll die from stress. So we decided to leave. My family is pretty close-knit and congenial, but in the evening, we’d get sad. That’s the most dangerous time to read the news. We’ve gone through stress, we’ve gone through fear and panic attacks. And now we’ve gone through the entire country.

We woke up at 5 a.m. and could hear sirens and screaming outside. My mother and brother were in shock. The dog was just happy to hang out.

One of us was in the middle of speaking when something exploded nearby. We held our breath and listened as hard as we could.

By sealing the windows, we cut ourselves off from the outside world. When the only thing you can do is listen, your imagination runs wild.

We told my grandmother we wanted to leave, and she said, “How are you going to leave your home?” My grandparents refused, no matter how much we begged them.

We got to the railway station and men weren’t allowed on the train. I could hear these soul-rending screams of women who had to leave their men in a city that was being bombed.

We left by car the next day. There were huge traffic jams, five or six hours long. When we stopped in Vinnytsia, we found out Russians had just bombed the airport eight times.

In Vinnytsia, a student dorm has been set up for refugees. My mother was tired after driving all day.

It was much calmer west of the Dnipro River since there are almost no hostilities on that side.

In Lviv, our friends lent us a three-room apartment. We’re drawing the curtains out of habit and turning off the lights so the enemy can’t see where to aim.

We woke up at 5 a.m. and could hear sirens and screaming outside. My mother and brother were in shock. The dog was just happy to hang out.

One of us was in the middle of speaking when something exploded nearby. We held our breath and listened as hard as we could.

By sealing the windows, we cut ourselves off from the outside world. When the only thing you can do is listen, your imagination runs wild.

We told my grandmother we wanted to leave, and she said, “How are you going to leave your home?” My grandparents refused, no matter how much we begged them.

We got to the railway station and men weren’t allowed on the train. I could hear these soul-rending screams of women who had to leave their men in a city that was being bombed.

We left by car the next day. There were huge traffic jams, five or six hours long. When we stopped in Vinnytsia, we found out Russians had just bombed the airport eight times.

In Vinnytsia, a student dorm has been set up for refugees. My mother was tired after driving all day.

It was much calmer west of the Dnipro River since there are almost no hostilities on that side.

In Lviv, our friends lent us a three-room apartment. We’re drawing the curtains out of habit and turning off the lights so the enemy can’t see where to aim.

Chapter 3

‘Not All Noises Mean Danger. Some Noises Mean We Are Fighting Back.”

March 2

Kherson falls, giving Russia its first major victory after suffering heavy losses.

.

Anastasiia Viekua

It’s the seventh day of the war, and we now have a reflexive reaction to the air-attack alarms. Everyone goes down to the bomb shelter very fast. Everything — the sound of a clap, or of slamming a door — makes you want to react by going downstairs.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

I keep writing in these various online groups that I’m open to helping anyone. A woman from Kyiv wrote to me: “Hello, I saw your message, could you take my cat?” She ended up giving the cat to a friend, but she gave us another of her pets. It’s a rat named Seryi, or “Gray.” It’s a sad story. The woman put Seryi in her pocket and traveled for eight hours, so the rat didn’t eat for eight hours, and that’s not good for rats. Stress makes them bleed from their eyes. We took it to the vet to get drops and salve. Anyway, the rat is safe now. It’s in a cage.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

I decided that after the war I will have a cat. And today I got a notification that at one shelter, there are 65 cats. So maybe I will grab one. I’ll call him Bayraktar, after a Turkish military drone our soldiers are using. Bayraktars are helping us deal with Russian tanks.

.

Viktoriia Khutorna

I’ve been working all the time. I’m an entertainment journalist, and we switched our entertainment website to show helpful news, like how to help a woman give birth in a safe place or where to find medicine. We’re also trying to work with our celebrities and bloggers to give Russian people an understanding of what is really going on in Ukraine, because they have no idea. The propaganda is so powerful.

We decided to do an experiment and watch Russian TV channels for an hour. They took this video of Volodymyr Zelenskyy saying he won’t give up, he won’t leave Kyiv, and he stands for Ukraine — and they edited it to make him say, “I’m giving up, I’m leaving Ukraine.” And they had a class broadcast all over Russia where they tried to explain to children that there is no war between Russia and Ukraine.

.

Masha Varnas, 27, a publicist and social-media manager in Odesa

Today was my birthday. I thought it would be the saddest birthday that I’ve ever had. But the leader at the train station where I’ve been volunteering remembered, even though I only mentioned it once. She got me a cake with white, pink, and purple roses — I’m not a great fan of sweets, but it was really nice to have this cake. Then my boyfriend called and asked me to come to the apartment building where his family lives, and there he was on the street with roses and this ring.

It’s not a real ring — it’s like imitation jewelry, plastic. But I was absolutely amazed. Even in this difficult time, he had found these things. The street is in a basic part of the city — a lot of cars, a lot of big buildings. It’s not a really beautiful place, but it’s beautiful and remarkable for me. It’s not about romance, about all these films where a guy makes a proposal at the Eiffel Tower or something. He said it was important for him to make this proposal now, because we don’t know how much time we have during this war. We are waiting to plan, though, because I want a long white dress, I want some flowers, and I want a little ceremony.

I’ve been thinking about having a child. Maybe I feel like my parents felt during the collapse of the Soviet Union in Ukraine, when people were not paid a salary. They didn’t have money, but they had a child. I think about them having me. I absolutely understand them now.

March 3

.

Julia Berdiyarova

I’m surprised by some of my friends who are going to fight. One of them used to be a fashionable guy — he was one of the pickiest buyers of the most expensive brands, and now he just picked up a gun and is in the army. Some of them are artists, musicians, people who in their everyday lives weren’t even thinking about the army. I have a friend in Dnipro who is a music producer, and now he’s a soldier. We talk every night. I don’t ask him where he is because he can’t tell me, so I ask him how he is. Sometimes we talk about what we will do after the end of the war — what food we’ll eat, where we’ll go, what we’ll drink. After this, we will sleep well, we will eat well, we will walk during the night and not only in the daytime.

He used to visit Kyiv when I was there, and we would go to a big park in the city center. In April, I think, there were magnolias blossoming and we had a picnic with cider and cheese. So we talked about how we’d have another picnic under magnolias or on the beach in Odesa. You can’t visit that beach right now: Ukrainian soldiers are waiting for Russian soldiers there in case there is an invasion from the ships. But as someone born in Odesa who spent her whole life near the sea, to have an opportunity to drink wine on the beach is like a dream about the future.

.

Aleksey

Since I arrived in Lviv, I have followed the news, but I try not to worry much because it is totally useless and causes nothing but heartache. I try to occupy my time with reading — I bought a George Orwell book. And my host is an IT specialist with an awesome computer setup, so I play Civilization VI, a global-strategy game.

I went to a warehouse to sort clothes, food, and medical supplies and then to a train station to help the Red Cross. I am a person who always tries to see at least something positive in any situation, and it was easy to feel this way in the warehouse, where there was a sense of unity with people occupied with a common purpose. However, it is quite difficult to volunteer at the train station and feel positive. You cannot avoid feeling the pain of the people who fill the station — women and children with blank stares. The only emotion you can read in their eyes is that they condemn this war and worry about their families.

.

Victoria Vlasenko

To be honest, I feel a little bit bored with work. I am not willing to work right now. I just want to drink tea and eat candies. I don’t know why, but it feels now like I deserve something good. I discussed with my husband what we will do after this all ends, and we will probably go to the most expensive restaurant because we feel that we deserve that. We have a little bit of victim psychology right now, I think. Everything’s closed except grocery stores. We’ve been cooking macaroni with peas and mushrooms, and bread is rare, so I learned how to bake bread. Not much else.

We have gas, electricity, and water, unlike some of the cities where there were really heavy fights. One of my colleagues has no electricity and is hiding in bunkers full time; she lost the connection with us because no electricity means she can’t charge her phone. The last time we talked with her, she was telling us that three bombs had hit her apartment block and all the windows in her home were shattered.

March 4

.

Nasta

Around 1 a.m., there was shelling at Energodar, where the Zaporizhzhya Nuclear Power Plant is located. I was just going to sleep and the news started to appear on my phone. It was not clear. All it said was: “The fire has started.” I felt as many emotions as I felt on the day the war began. My mother and our other relatives live in Zaporizhzhya. I felt that anything could happen and I wouldn’t be able to help in any way. It started to feel like I went numb. I called my mother to check on her. She was asleep — she answered in her sleepy voice — and I just said, “There is a fire going on, go back to sleep, I will call you if you need to leave or do something to save your life.” I kept checking the news, and at 4 a.m., just as I was finally ready to sleep, another siren went off in Kyiv.

.

Liana Muradian, 24, a medical student in Ivano-Frankivsk

My mother lives in Kherson, where there is extremely heavy fighting. I’m an only child, and Mom is trying to shelter me from bad news, but I understand that it is scary. There has been no gas supply — she heats up her place by turning on the oven and opening its door. She’s my main concern right now. We talked yesterday, but today there was no internet connection with Kherson.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

Today is definitely a good day. We slept for six hours, because it was the first night that the Russians stopped bombing us into the morning. Although you are also terrified to get sleep because when you wake up, your country may have fallen. So when you wake up, you’re alert and you’re screaming because you really need to know from a person who’s already up: How is everything going? What happened?

My relatives are desperate. They are thinking that the war might be happening for months. And our town has run out of food, and more troops are coming from Russia.

.

Victoria Vlasenko

As usual, I was hearing noises outside. In the beginning of the war, I was thinking they were all bombs that were falling on my city. But I’ve learned that some of the noises were not us being attacked but rather our own army’s bombs. It’s good to know that not all the noises mean danger. Some noises mean that we are fighting back.

.

Viktoriia Khutorna

Today is my 25th birthday. My relatives gathered in the kitchen and said they have a present for me: some towels and a cup to keep my beverages hot. And at dinner, my uncle gave a toast and my cousin’s husband made crème brûlée. It’s strange and difficult to have a birthday now. Everyone — my colleagues, my friends — they all wished me peace and to see my family soon. Even my friend who is currently hiding in his basement in a village near Ivankiv still managed to wish me a happy birthday.

.

Nasta

We went to the shelter two or three times today because of the sirens. But mostly we stayed at home. The shelling was pretty constant, so close that we felt our house shaking. Still, there was lots of news today about new babies being born in Kyiv. That was comforting. You see life going on, that life is not destroyed completely. The funny thing is that there have been animals given names like Bayraktar. So we’re joking that in 30 years, there will be a lot of adults named Bayraktar, too.

March 5

.

Viktoriia Khutorna

We decided to move further west very, very late last night. We were thinking about it and then my cousin came to our room when we were almost asleep and said, “Hey, we are planning to move. Will you come with us?” We decided that yes, we should. We packed our stuff, and this morning a big group of us drove away just before nine. When the cars started to go, I thought, This is it. My life is changed. I’m not going to live in my house or in my relatives’ house.

The western part of Ukraine is a whole new area for me. The mountains were breathtaking; the Carpathians are the most beautiful landscape you could ever see. And we saw a couple of great castles along the way. The first one was in the city of Kamyanets-Podilskyy — it’s famous for its castles. We definitely will see it sometime after we come back home. I believe it.

.

Vova Prylutskyi, 22, a photographer from Kyiv

Minutes before our train left the railway station, my friends and I found a place to stay in Lviv at the home of a friend. There were eight people in the apartment when we arrived, including Oleksii and Sasha, two friends from Kharkiv whom I met more than a year ago. Most of the time we spent volunteering. We’d load and unload humanitarian aid, make camouflage for tanks, help people navigate the railway station. Here, Oleksii and Sasha are sitting in the bomb shelter during air sirens.

.

Victoria Vlasenko

My mom is panicking. She’s not here; she’s in Israel visiting her mother. She cares about my sister a little more than me because my sister has a health condition; my mom wants to come here and move her somewhere to the west, along with my brother. She didn’t invite me. I don’t know why; probably because I’m the most okay out of everyone.

I don’t want my mom to come here — it’s a lot better for her to stay in Israel. But what can I do if a mother wants to save her children?

.

Anastasiia Viekua

My parents have this idea that it’ll all be over soon. As for me, I know that even if it doesn’t last long, we’ll have economic devastation. I’m trying to stick to reality so as not to be disappointed.

.

Yehor Shatailo, 28, a stand-up comic from Kyiv

I’m safe in a relatively quiet city in central Ukraine, but for the first couple of days after getting here from Kyiv I was still in a state of shock. Mainly because I never had a chance to say good-bye to my girlfriend, who had to stay there with her family. And then her father was killed. He was a doctor trying to save his patient. That’s fucking tough. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat. I was losing it because there was no way to know whether she was safe. Now she’s managed to flee — she actually visited me on her way to the west.

There were two moments when I realized I was feeling better. The first was when I let myself play Disgaea 5 on the Nintendo Switch I brought with me. The other was when I started to work on new material. I do believe comedy has a huge role to play in times of war. Our sense of humor is still there; the need for comedy is still there. Although in the state I’m in now, the best joke for me is the Russian occupying forces getting their heads shot. And the best punch line is a Russian tank blowing up. That’s what cracks me up now.

There’s no need to overestimate the power comedy has. It’s not a weapon; I don’t think I can heal any wounds. But it might help us to stay sane.

I’m planning to organize some comedy shows in this city I’m in now. All we have to do is find a safe shelter, a mic, and a sound system. It goes without saying that part of the proceeds will go to Ukrainian-army support funds. What will the first stand-up comedy night at Kyiv’s clubs after the victory look like? I presume there will be two diametrically opposed themes. Naturally there will be war jokes. And there will be some absurd shit, Steve Martin style. I don’t think there will be any middle ground. There’s no middle ground now.

March 6

Russian forces strike evacuation routes, killing four civilians fleeing Irpin, outside Kyiv.

.

Anastasiia Viekua

I lost my friend Pasha Lee — he was killed today by a Russian sniper. He was volunteering, evacuating people from Irpin, when he was shot. His car burned with him inside. So there is no body for his relatives to bury. I received a voice message from him just two days ago. He’s singing a national anthem and saying in the end we’re together.

Pasha was an actor, and I met him when I was taking acting classes that he was giving. I have never known any other person who was so in love with people. When you met him for the first time, it felt like he really wanted to know you. One woman in the class was incredibly toxic, but Pasha gave her chances all the time, and he tried his best to find a way to her, trying different things to make her comfortable. He was a believer in people’s potential.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

Yesterday I had a collapse — I was unable to walk or go to the bathroom. I was so dizzy that I stayed in bed and worked during the night. All day we’ve been coordinating with friends around the world to find the lists of things people need. One of my friends got ten bulletproof vests, and did it illegally. Another friend bought two ambulances. How on earth do you buy two ambulances? We need men’s footwear in a really huge size, so I texted my gym to ask for it. I’m also looking for one bulletproof helmet and a very specific cancer medication.

.

Julia Berdiyarova

My family tried to watch a film, Narnia. We had watched the first part on the first day of the invasion. Now, after a week of this hell, we tried to watch the rest, but it was too naïve — too much about dreams and not reality. It’s like you’re trying to concentrate on something good and in fairy tales, because they always end well, and you want to believe this hell will end soon and that this too will end well and all the people who fight for us will be safe. Unfortunately, now I know a lot of people who are dead. They were volunteers who were killed by Russian soldiers. So we just tried to find another film.

We heard from our president that we could expect shelling in Odesa. We all know that Odesa may be next. But I feel safe here, and I believe in our army. I’ve never had this feeling before: I’m not a person of war, and in peaceful times, you don’t think about the army. But when you are in a war, when you are in danger, you have a very close relationship with this institution, and you do everything to help them. I understand that not all of them are good people in everyday life — maybe they are toxic guys — but now I don’t care. When war ends, we will discuss it; there will be time for a dialogue. But now is not the time for a dialogue.

.

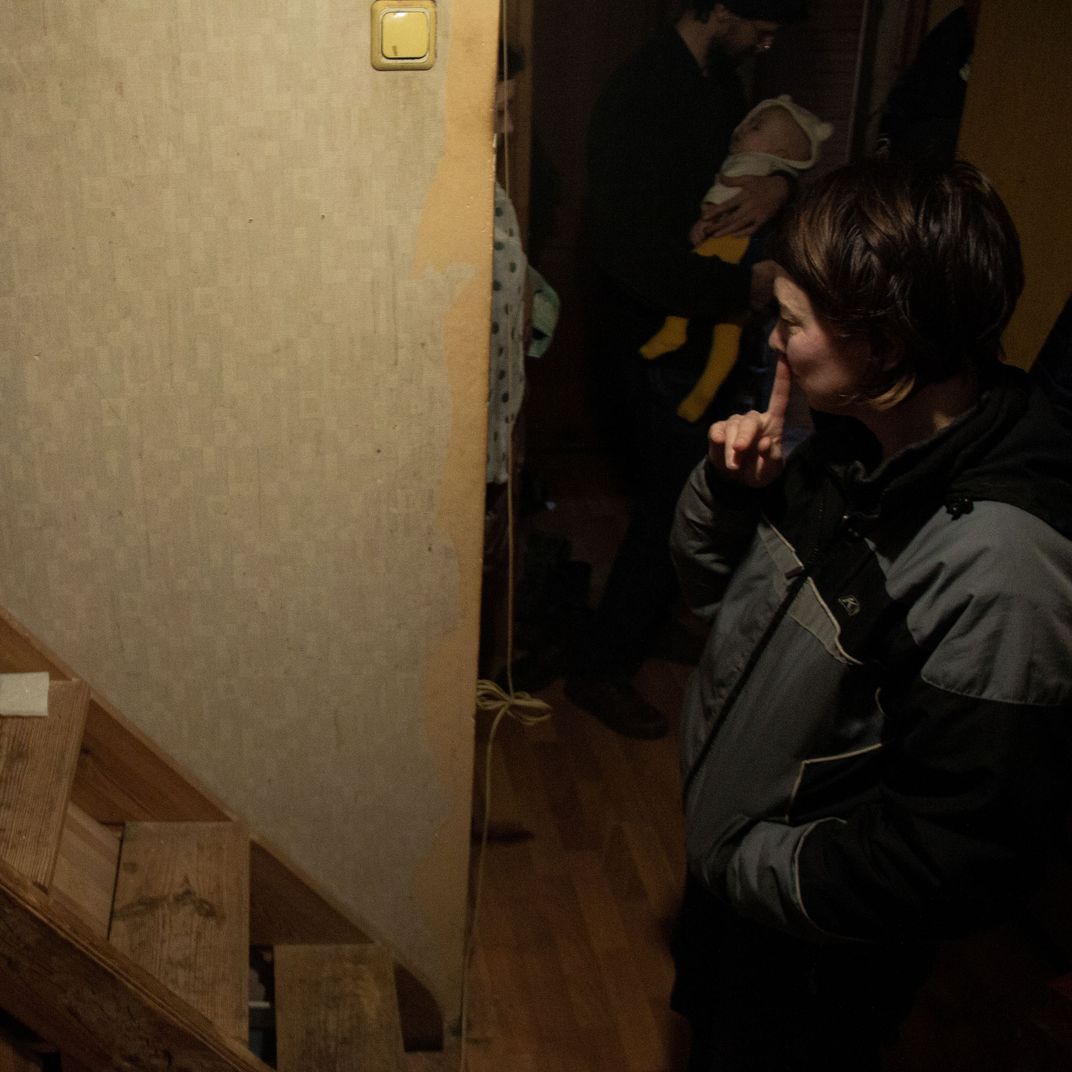

Polina Polikarpova, 29, a photographer in Kyiv

I made this self-portrait after escaping to the shelter one night. Our neighbors tried to make it more comfortable, so we all did a cleanup and brought mattresses, pallets, blankets, and pillows. Someone wired electricity but that went down quickly. So we kept lighting candles under a picture of mother Mary, aided by flashlights in our pockets. We chat to stop the growing anxiety. Once, after we spent some time down here, someone with good phone service got news of an air-alert cancellation. Everyone got up quickly and wished each other that they never meet here again, at least in the middle of the night.

Chapter 4

‘You Need Your Whole Salary to Buy a Bullet-Proof Vest’

March 7

More than 2 million people have fled Ukraine since the invasion.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

Forgetting about what’s happening is, for me, impossible. But I understand you have to try to distract yourself. We spend time with friends; I spend time with the rat we’re fostering. I write poems, too. You’re still writing about the war, but it does shift your attention, because just sitting there and reading news and fear — it’s unbearable.

It sounds horrible, but truly it’s become a bit of a routine for the whole country and for me in particular. We joke about it; we talk about it. All these notifications about shootings, victims, pictures of the dead, dead children — because there are dozens of them now — you just respond to it with emotions that aren’t as powerful. You’ve accepted the situation. There’s a sense that there’s no other way, you have to just live through it because it will end. We know we’ll win. Dying isn’t an option, and you don’t really want to now. I had thoughts like that in peacetime — exactly a month ago, I saw a psychiatrist for the first time, and she diagnosed me with depression, long-term depression. But I don’t have a single thought like that now.

.

Lesyk Yakymchuk, 29, a graduate student returning to Kyiv from Ohio

I don’t know how much longer anybody can be positive. This is not like regular bombing. You can’t even see this bombing. Nothing is damaged inside of the city, but you’re just lying in the city at night and suddenly you hear this alarm that you have to go to the shelter. You can’t properly sleep. Everyone is just exhausted from this endless, endless stress. This endless, endless fear.

When this all started, I was in a graduate program at Ohio University. I gave some lectures and talked to students on campus about what Ukraine is and why this war is important for the entire world. But after two days, my girlfriend, Olena — she is also Ukrainian — and I understood that we were not doing enough and that we couldn’t stay in Ohio. We gathered some medical supplies, and on the 27th, we flew to Poland. From there, we took my cousin’s car to the border with Ukraine, and that was the turning point for me. Before that moment, I had thought, I can stay in Ohio, I can be wherever, I can be a free man even if my country does not exist. But after you cross the border, you have a feeling: This is it. You have to go on to victory.

It was a long, long drive to Kyiv because the main road is not safe and we were trying to use hidden roads. It was completely insane — there could be Russian troops anywhere, and people were really, really scared. Since then, we’ve been driving supplies between Lviv and Kyiv. It’s a lot of medical stuff: tourniquets, dressings, chest seals, skin staples, surgical staples. Sometimes it’s military stuff — not guns but armor, helmets. It’s me and my girlfriend up front and all the boxes and supplies packed fully in the back.

Sometimes we are feeling upset, really depressed. But then we’ll start to feel hope and start smiling. It’s like a circle from emotionally inspired to depressed. My friend who is now in Kherson called me, crying hysterically, begging me to take his girlfriend to a safe place. He was screaming about genocide in Kherson: “They’re killing people on the street!” I was in shock. You can’t do anything. You want to teleport yourself to him to save him.

.

Masha Varnas

We got the longest alarm today. When it started, my boyfriend and I were outside on the street and we walked to the basement where we work with other volunteers preparing food. But it’s interesting that when the sirens sound, people in Odesa don’t run. They don’t panic.

Tomorrow is International Women’s Day, a very important day for all Ukrainians. In western countries, people think that this day is about feminism, but in Ukraine, people think it is about women and their beauty. There are a lot of flower sellers at the market in the city center, and they get to raise their prices. And even during this siren, people continued to buy flowers and bring them to their women. People in Odesa are too calm. They think about tomorrow and about flowers and about women, and, while the alarm sounds, they walk with dogs and children on the streets.

Maybe they don’t understand how serious the situation is. They don’t understand that a real war is going on and that Odesa is a special city, a port city — an important city for the Russians.

.

Julia Berdiyarova

My family and I talk of leaving Odesa. We have contacts in different cities. But my friends who have left and are in Moldova, Romania, or Bulgaria — they feel so bad. They write to me saying that this is not their life, that they want to come home. It’s hard to leave your home. Here, I have my bed, my clothes. I have my own flat, I have my own work, I have my own money. When you have to leave, nothing is yours and you have to ask for help. My father is a seaman, and right now he is on a ship in the ocean. He reads the news every day, and he tells us “Please leave” every day. But I told him that I don’t want to leave. I don’t want this status of a refugee. I think when the first bomb hits Odesa, or when the soldiers come to this region, it will be time to leave. But right now Odesa is a strong city. I told my mother if she stays, we stay. We made this decision to be together till the end.

March 8

.

Anastasia Kovalchuk

As soon as it gets dark outside, we do not turn on the lights because Russian soldiers can shoot through the windows. When the siren sounds, we quickly sit in the corridor because that is the safest place. It’s dangerous to go outside now, so I’m trying to stay at home most of the days. I dream of putting on my favorite pajamas and walking around in them all day, rather than sleeping in the clothes I have to run to shelter in.

.

Victoria Vlasenko

Every day, my family tries to stay in touch. My father calls me, my granny calls me, my sister texts me. For me, it’s not easy. I’m an introvert, and I know it sounds like I’m a monster or something, but I would like to not have to communicate with them this much.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

The rat is totally shameless now. He has this weird habit of kissing you. Before, he’d kiss you on the lips, but now he tries to pry open your lips with his little hands and put his tongue in your mouth. He wakes up, comes to the door of the cage, and starts scratching around because he knows it’s his house now. He knows how to get on the bed, on the desk, on the floor, into another room. I leave out little sweets for him. That’s my hobby for the moment. He’s a lot better, but he still scratches at his eye, so every few hours we put salve on it. He squeaks, but he doesn’t bite.

.

Aleksey

A number of my friends ended up in Lviv recently, and I’m starting to feel like my Kyiv diaspora is taking shape, creating a comfort zone for me. But, of course, I am endlessly missing the home I left behind. I’m concerned that this war will become a prolonged state, a long-lasting conflict, like what we have had with Donbas for the past eight years.

.

Lesyk Yakymchuk

On one hand, Kyiv is the same city I used to know. But it’s also a different, cold city. There’s not many people out, not many cars. No one turns on their lights at home. It’s postapocalyptic, a bit, but I’m still feeling that I’m at home. This is my place to stay; I’m just lying on my bed that I used when I was a child.

Before the invasion, I was meditating, playing music, doing a lot of interesting stuff. But now I can’t think about anything except the war. The feeling in the city is a silence before the storm. We’re afraid of another escalation. Our soldiers can deal with everything on the ground, but we can’t deal with missiles. While we watch what they did to Kherson and Kharkiv, it’s a lot of anxiousness, because what if they do some big thing like that in Kyiv? I’m planning to stay here, but who knows? Maybe I will need to take a gun and go to join the Territorial Defense. Oh, wait a minute. It’s a siren. I need to go.

March 9

Russia bombs a maternity hospital in Mariupol, where officials say more than 1,000 civilians have been killed.

.

Danyil Zadorozhyni

I had my first night shift at the Lviv train station. We worked for 14 or 15 hours. There’s a tent city there now — bonfires in canisters, huge tents where volunteers pass out food, tons of people with weapons. There’s a vast number of women and children sleeping on the ground, using who-knows-what for blankets, on cardboard, with dogs. People in wheelchairs. I was asked to bring a mattress for a grandmother: She’s about 90, she’s got tremors, and I helped put her on the mattress and cover her with a blanket, and her family sat on the floor next to her because there was no room anywhere else.

I was upset because, as a volunteer, you want to help people, but you can’t help everyone, and you see an enormous — I’ve never seen such a mass of pain and suffering and grief with my own eyes. I was stationed at the entrance of a waiting room where we could only let in mothers with children under 5. Only them. Because the station isn’t meant for this many people, we can’t let in everyone. I had to turn people away: “Your kid is 10. You can go to the next waiting room.” And they said, “We just came from there. There’s no room.” We were supposed to turn away disabled people because there was a different room for them. But we’d still let them in. And there was a huge amount of Roma people who are asking to get in. There was a horrible episode where a little girl was crying; her grandmother pushed the girl to the ground and kicked her, and I ran there and pulled her away. It was a shock. You see that people just live like that and you can’t do anything about it. And it was that way all night. In the baby room, there were a lot of women volunteers, and they often cried because they saw mothers and children, kids who were 6 months old, spending 20 hours on the train escaping bombing and then they have to travel to Poland. It’s painful. You have to shut off your empathy because otherwise you can’t do your job.

I slept through the next day, which was yesterday, and then today is a day off for us. Yulya and I are going to get her passport translated because we need that to get married. When else should we do it if not now? Tomorrow we’ll volunteer again.

.

Mariia Shuvalova

I haven’t personally known people who’ve been hurt, but yesterday that started happening. My friend’s parents live near Ivankiv, and the whole town was bombed. They made a video: There is nothing left of the city, and they still haven’t found the mom. Today, my close friend said her family member was killed. And my friend from Bucha wrote on Facebook that her beautiful house was completely destroyed. They are injured and homeless now.

Right now, you need your whole salary to buy a bulletproof vest, which costs $1,000. My brother has one; his team is patrolling in Kyiv. He told me there are so many people who want to protect cities that the government is not able to provide everyone with everything.

Each night, after midnight, off-duty Ukrainian soldiers post voice chats on social media. They explain to us what “official reports” mean. They are honest and tell us that some cities are devastated, that it’s extremely bad. They ask us to eat carrots, do physical exercises, and keep working. They are telling us, You don’t have to feel guilty.

On the first day of the war, I made a group chat and called it “War.” There are 11 Ukrainian girls in different countries — Ukraine, Norway, France, Germany — and in the evening we do video chats. It’s a time to behave badly and to be very negative. We are almost 30 years old, and we are intelligent ladies who like literature and all wear glasses, but we join this chat and we are swearing like bastards, like robbers, like people in prison.

.

Svyatoslav Fursin, 24, an IT engineer in Kyiv

A few hours after the invasion, my fiancée called me and said we should go ahead and get married in case the war starts. After we exited the church, we heard the sirens and alarms. Our wedding celebration started in the shelter. My wife and I joined the Territorial Defense the next day — I lived in occupied Crimea for four years, and I don’t want my country to become like that. My first mission was to organize an ambush for the enemy tanks, and the first night was the scariest. We were catastrophically unprepared. We just arrived with the weapons given to us, and I was very worried for my brothers because some don’t know how to handle them. But luckily, the frontline army was able to stop the Russian attack. This gave us time the next day to prepare our positions much better.

.

Masha Varnas

Today, me and the volunteers, we had a day off from feeding people at the station. We decided to just meet and eat together. We’re trying to joke and discuss the news in a good and fun way and to make some plans for what we’ll do after the war. The girls think about clothes that they will buy at Zara. It’s nice to spend time with all these new people, your new war friends. We met, like, nine or ten days ago, and it was really unexpected for me to spend all this time in a basement kitchen with them. Some of them are very religious, and some others don’t know how to deal with the situation, but it’s cool that all of us are together.

Before going to bed, I listen and watch ASMR videos: People speak in a quiet voice and make pleasant sounds, and it helps me sleep. Also, I cannot hear my own bad thoughts.

I’m going back to work as a publicist soon and then I will not be able to volunteer. I need the money — there is no help from our government.

.

Leonid and Nasta

Nasta: We went grocery shopping, as we are running low on food. My brother went to buy water, but the shelves were empty.

Leonid: When I spoke to our grandmother yesterday, I wished her the usual things: happiness, good health, and the death of Putin.

March 10

Odesa prepares for a Russian assault. Both sides have lost thousands of troops.

.

Anastasiia Viekua

Three different stories about my friend Pasha’s death appeared in the media today, each more fantastic than the last. His beloved had started asking everyone who was with him last. Everybody said he was injured by a bullet and then they lost sight of him, but all of them shared different accounts, and it turns out that nobody actually saw him dead. His mom’s claiming he’s alive. So now a bunch of his friends are trying to find him, but that’s complicated — the part of Irpin where somebody saw him for the last time is occupied by Russians. The more friends try to look for him, the more versions of the story keep appearing. Now it feels even harder, as we don’t know the actual truth. I don’t know what to feel. I can’t grieve, as there might be hope, and I can’t be sad, as it might be a fantasy.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi

They’re starting to fortify some buildings in Lviv. I’m saying this with some discretion because we have official information that we’re asked not to talk about because it might be useful information for the enemy.

There are more people here now, objectively more. Our mayor said we’re approaching capacity. It’s really hard because there’s nowhere to put any more people. It’s just a lot of people. So many people. As far as I can see.

.

Sana Shahmuradova, 25, a painter from Kyiv

As they were escaping Kyiv by car, my friends came and picked me up. I didn’t have much time to think, I just knew I had to get to my grandmother because she is all alone in the countryside. I left Kyiv with no materials, but here at my grandmother’s I recalled my old habit to sketch on wallpaper scraps. I found some old crayons and gouache that my younger brother left while visiting last summer, and some charcoal. The ladies with the flag and tank in this painting appeared from my impression of the Kherson Defenders. One of the men jumped on a tank with a Ukrainian flag waving in his arms. You can see “fuck off” written on the tank in Ukrainian.

.

Viktoriia Khutorna