- REVIEW

- READER REVIEWS

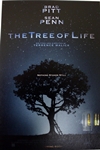

The Tree of Life

|

|

Genre

Drama, SciFi/Fantasy

Producer

Dede Gardner, Sarah Green, Grant Hill, William Pohlad

Distributor

Fox Searchlight

Release Date

May 27, 2011

Release Notes

Limited

Official Website

Review

In his fifth feature, The Tree of Life, the visionary director Terrence Malick uses every cinematic tool under heaven to trace the connections between the fleeting and the infinite—and if that sounds fancy, then Lord, you ain’t heard nothing yet. This is Malick’s big one, his long-gestating answer to 2001 and Paradise Lost, and it’s wedded to his (maybe) autobiographical Oedipal family drama of life in the fifties in Texas under a brutish but increasingly impotent father (Brad Pitt) and a diaphanously beautiful mother (Jessica Chastain) who embodies the spirit of Grace. I’m not reading into it: She ruminates in voice-over on “the way of Grace” versus “the way of Nature,” which will make things a lot easier for students writing papers.

There is the suggestion of a narrative: The protagonist is a boy, Jack O’Brien (Hunter McCracken), of increasingly wayward emotions who adores his mom and wishes aloud for his dad to die. But it’s better to think of The Tree of Life as a Transcendentalist church pageant in which the players whisper questions to the Almighty after the death of a son and brother (“Where were You?” “How did I lose You?”)—followed by nothing less than the birth of the universe, the beginning of cellular life, some dinosaurs, and then children swimming into the Garden of Eden that is Waco. And it’s all filtered through the memory of Jack as a grown-up (Sean Penn), seen both in a glass-and-steel metropolis and on the rocky, vaguely primordial beach that represents his inner world. After warming up with The Thin Red Line and The New World, Malick has succeeded in fully creating his own film syntax, his own temporal reality, and lo, it is … kind of goofy. But riveting.

Malick’s vantage—and that of his cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki—is the oddest combination of the archetypal and the impressionistic, with a lot of trailing after the characters and then hovering. Pitt, who co-produced the film and had to speak for Malick when the director blew off a Cannes press conference, put it well: Malick is “like a guy with a big butterfly net, waiting for a moment of truth to go by.” And those disconnected moments are woven together to make the film amazingly fluid. (There are five, count ’em, credited editors.)

Malick is often likened to Stanley Kubrick, who meticulously composed his shots and often needed scores of takes to get exactly what he wanted. (He drove actors crazy.) If anything, Malick is the anti-Kubrick. To help him design the long section in which the universe, the Earth, and life begin, Malick turned to Douglas Trumbull, best known for 2001, but this time, the effects have spiritual depth. Trumbull has spoken of Malick “hunting for the Tao … those magical unexpected moments that no one could possibly design.” But wait, aren’t they designed? Some of them are, closely inspired by the latest science. Most, however, are freaky. What is that image that launches each of the film’s sections? It appears to be the cosmos in its infancy, yet the shape is angelic, with an opening that could well be meant as a portal to heaven. Then come the undersea shots: coil-like life forms, blobby jellyfish, hammerhead sharks, Jar Jar Binks. Well, he’s not as repulsive as Jar Jar, but he’s somewhat anthropomorphized. Where Kubrick’s first section of 2001 built to a scene of an early human finding a tool with which to kill, Malick shows a predatory dinosaur stopping himself from stomping a fallen dino to death. It’s the first stirring of compassion.

For a “personal” director, though, Malick can be curiously impersonal. No image is allowed to be non-archetypal. Low-angle shots of boys climbing a tree, heavenward: That’s a recurrent motif. So is water, symbolizing birth and death. (The movie feels as if it were processed in amniotic fluid.) Chastain is a willowy redhead with bright eyes and skin so fair that you feel as if you’re seeing into her soul. Her 2008 performance in Jolene was revelatory—she has the potential to be a major actress—and yet Malick turns her into an object, the sort of ethereal creature on whom butterflies land. She and the other actors spend a lot of screen time tottering among trees looking bereft while the soundtrack serves up too many familiar chestnuts: Brahms, Smetana, Mahler, Holst, and the de rigueur Ligeti, in the mode of 2001.

As the boy Jack, McCracken is terrific—meaning good and terrifying—with stuck-out ears that are perfect for a patriarch to twist and, as the character’s hormones kick in, a hint of something wilder and more sexually violent. The Fall approaches. A boy drowns at a public beach, another is badly burned, and pretty soon Jack starts to play with BB guns. He and his buddies blow up a nest of eggs. (“Why should I be good if You aren’t?” he asks, in voice-over.) Reptiles appear. Then Jack begins to gaze longingly at his ripely erotic mother and angrily at his square-jawed father. (Pitt plays the dad with the right mix of paternalism and emotional detachment.) There’s a dash of homoeroticism in a scene between Jack and the blond brother who we know is destined to die in his teens. (In a war? It’s never clear.) It’s tantalizing stuff, suggesting the psychosexual underpinnings of all those Malick versions of heaven and hell.

And then it stops dead. A giant part of the story—the last act—is missing, as if Malick skipped a bunch of pages in the prayer book to get to the final hymn. The father, who has attempted to patent his inventions and lost every case, now loses his job. The family must move. As they drove away from the now-empty house, I thought, “That’s what we’ve been building to for two-plus hours? Leaving Waco?”

The Tree of Life is meant to portray the attempt of a man (Jack) who’s fallen from grace to return to the Garden, to make peace with a God he’ll never know or understand. But what exactly did he do wrong? There’s little hint in Penn’s Jack, who looks suitably stricken but is underwritten, and the final sequence—everyone from his past on a beach, hugging—is an embarrassment. Why did Malick stop in mid-arc? He either has no basic storytelling instincts or else purged them after all that time at Harvard with Stanley Cavell reading Heidegger and questioning whether we actually exist. My hunch is that existence precedes writing characters with essence.

The Tree of Life doesn’t jell, but it goes without saying that I recommend it unreservedly. Will you find it ridiculously sublime or sublimely ridiculous? Don’t be afraid to find it both.